It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World

| It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World | |

|---|---|

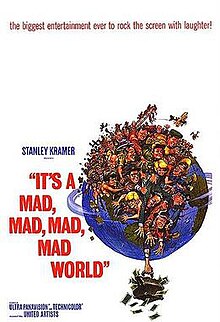

Theatrical release poster by Jack Davis | |

| Directed by | Stanley Kramer |

| Written by |

|

| Produced by | Stanley Kramer |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Ernest Laszlo |

| Edited by | |

| Music by | Ernest Gold |

Production company | Casey Productions |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release date |

|

Running time |

|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $9.4 million[1] |

| Box office | $60 million[2] |

It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World is a 1963 American epic comedy film produced and directed by Stanley Kramer with a story and screenplay by William Rose and Tania Rose. The film, starring Spencer Tracy with an all-star cast of comedians, is about the madcap pursuit of a suitcase full of stolen cash by a colorful group of strangers. It premiered on November 7, 1963.[3] The principal cast features Edie Adams, Milton Berle, Sid Caesar, Buddy Hackett, Ethel Merman, Dorothy Provine, Mickey Rooney, Dick Shawn, Phil Silvers, Terry-Thomas, and Jonathan Winters.

The film marked the first time Kramer directed a comedy, though he had produced the comedy So This Is New York in 1948. He is best known for producing and directing, in his own words, "heavy drama" about social problems, such as The Defiant Ones, Inherit the Wind, Judgment at Nuremberg, and Guess Who's Coming to Dinner. His first attempt at directing a comedy film paid off immensely as It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World became a critical and commercial success and was nominated for six Academy Awards, winning for Best Sound Editing, and two Golden Globe Awards.

The film premiered on November 7, 1963 at the Cinerama Dome with a running time of 192 minutes. However, against Kramer's wishes, the film was cut by its distributor United Artists to reduce the film's running time to 163 minutes for its general release. In 2014, the Criterion Collection released a restored version that is closer to the original 202-minute version envisioned by Kramer.

The film featured at number 40 in the American Film Institute's list 100 Years...100 Laughs.

Plot

[edit]Smiler Grogan, a recently released convict, crashes his car on California State Route 74. With his dying breath, Grogan tells a group of motorists who stop to help him about $350,000 (equivalent to $3,483,261 in 2023) buried in Santa Rosita State Park under "a big W." Failing to negotiate a satisfactory way to split the money, the four cars begin a mad dash to the park, having several mishaps along the way:

- Melville Crump, a dentist on a second honeymoon with his wife Monica, charters a rickety biplane to Santa Rosita. Despite arriving in Santa Rosita first, they get locked in a hardware store's basement. After several attempts to break out, they blow out the wall of the basement with dynamite, and hire a cab to get to the park.

- Ding Bell and Benjy Benjamin, two friends on their way to Las Vegas, charter a small airplane. When their alcoholic pilot knocks himself out, they struggle to land the plane themselves; once on the ground, they also hire a cab to get to the park.

- J. Russell Finch, a businessman traveling with his wife Emmeline and her mother Mrs. Marcus, crashes into the furniture truck of Lennie Pike, another witness of Grogan’s crash. Finch persuades British Army Lieutenant Colonel J. Algernon Hawthorne to drive them to Santa Rosita. After a nasty argument, Mrs. Marcus and Emmeline exit the car to hitch their own ride. Hawthorne crashes the car while driving through a tunnel, and he and Finch come to blows.

- Pike stops motorist Otto Meyer for a ride and tells him about the money; the greedy Meyer decides to search for the treasure himself, and abandons Pike, convincing two service station attendants to detain him. Pike destroys the station, steals a tow truck, and picks up Mrs. Marcus and Emmeline. Mrs. Marcus calls her son Sylvester, who lives close to Santa Rosita, but he misunderstands and drives to meet her. Eventually, the group reunites with Russell and Hawthorne, and continues to head to the park.

- Meyer stops to help a stranded miner get back to his very rural cabin. Trying to get back to the highway, Meyer fails at crossing a deep river and his car is swept away, leading him to steal another motorist's car.

Meanwhile, Santa Rosita Police Captain T. G. Culpeper, hoping to tie up the Grogan case before his impending retirement, secretly has the motorists shadowed throughout their various adventures. After a furious argument with his wife and daughter, Culpeper learns that his pension will be a pittance and has a mental breakdown.

The entire group, now consisting of fourteen people, arrives at Santa Rosita at nearly the same time, and searches frantically for the "big W", which turns out to be a gathering of four palm trees. Culpeper arrives shortly after and observes the group. After the group digs up a suitcase full of cash, Culpeper identifies himself and informs the group that they are wanted by the police. He convinces them to turn themselves in and hope for leniency.

The motorists realize that Culpeper is not returning to the police station with them, but is stealing the money for himself. The men chase him into an abandoned building and onto a rickety fire escape, which starts to collapse under them. The briefcase containing the money falls open, scattering the cash to the wind. When Culpeper and the men all pile onto a fire department ladder sent to rescue them, their combined weight causes it to spin uncontrollably and fling them all off, leaving them heavily injured.

In the prison hospital, the men bemoan the loss of the money and blame their injuries on Culpeper, who responds that due to his lost pension (which his boss had successfully negotiated back, thus making his illegal actions unnecessary), the ruined relationship with his family, and the likelihood that the judge will probably give him the harshest sentence, he may never laugh again. Mrs. Marcus, flanked by Emmeline and Monica, enters and begins berating the men, only for her to slip on a banana peel and fall. All the men except Sylvester roar with laughter, and, after a brief hesitation, Culpeper joins in.

Cast

[edit]Principal cast

[edit]- Spencer Tracy as Captain T. G. Culpeper

- Milton Berle as J. Russell Finch

- Sid Caesar as Melville Crump

- Buddy Hackett as "Benjy" Benjamin

- Ethel Merman as Mrs. Marcus

- Mickey Rooney as Ding Bell

- Dick Shawn as Sylvester Marcus

- Phil Silvers as Otto Meyer

- Terry-Thomas as Lt. Col. J. Algernon Hawthorne

- Jonathan Winters as Lennie Pike

- Edie Adams as Monica Crump

- Dorothy Provine as Emeline Marcus-Finch

Supporting cast

[edit]- Eddie "Rochester" Anderson as a cab driver

- Jim Backus as airplane owner Tyler Fitzgerald

- Ben Blue as the vintage biplane pilot

- Joe E. Brown as the union official giving a speech at a construction site

- Alan Carney as a sergeant with the Santa Rosita Police Department

- Chick Chandler as a policeman outside Ray & Irwin's Garage[4]

- Barrie Chase as Sylvester Marcus' dancing, bikini-clad paramour

- Lloyd Corrigan as the mayor of Santa Rosita

- William Demarest as Aloysius, Chief of the Santa Rosita Police Department

- Andy Devine as the sheriff of Crockett County, California

- Selma Diamond as Ginger Culpeper (voice)[4]

- Peter Falk as a cab driver

- Norman Fell as primary detective at the "Smiler" Grogan accident site

- Paul Ford as Col. Wilberforce

- Stan Freberg as a deputy sheriff of Crockett County

- Louise Glenn as Billie Sue Culpeper (voice)[4]

- Leo Gorcey as the cab driver bringing Melville and Monica to the hardware store

- Sterling Holloway as the Santa Rosita Fire Department fireman

- Edward Everett Horton as Mr. Dinkler, owner of the hardware store

- Marvin Kaplan as service station co-owner Irwin

- Buster Keaton as Jimmy the Crook

- Don Knotts as the nervous motorist

- Charles Lane as the airport manager

- Mike Mazurki as the miner bringing medicine to his wife

- Charles McGraw as Lt. Mathews of the Santa Rosita Police Department

- Cliff Norton as reporter (scene deleted)[5]

- ZaSu Pitts as Gertie, the Santa Rosita Police Department Central Division's switchboard operator

- Carl Reiner as the Rancho Conejo airport tower controller

- Madlyn Rhue as secretary Schwartz of the Santa Rosita Police Department

- Roy Roberts as policeman outside Irwin & Ray's Garage

- Arnold Stang as service station co-owner Ray

- Nick Stewart as the migrant truck driver forced off the road

- The Three Stooges (Moe Howard, Larry Fine, and Curly Joe DeRita) as Rancho Conejo Airport firemen

- Sammee Tong as a laundryman

- Jesse White as a Rancho Conejo air traffic controller

- Jimmy Durante as Smiler Grogan

Cameo/uncredited appearances

[edit]- Jack Benny as man driving car in desert[4][6]

- Paul Birch as a patrolman[4]

- John Clarke as a Santa Rosita Police Department helicopter pilot[7]

- Stanley Clements as a reporter[4]

- Phil Arnold as a Gas Station Attendant (Scene Deleted) [4]

- Minta Durfee as a woman in the crowd[8]

- Roy Engel as a patrolman[4]

- James Flavin as a crossroads patrolman (scene deleted from general release version)

- Nicholas Georgiade as detective at crash site[4]

- Stacy Harris as police radio voice unit F-7 (voice only), and as a detective outside of Mr. Dinkler's hardware store [citation needed]

- Don C. Harvey as helicopter observer[4]

- Allen Jenkins as a police officer[4]

- Robert Karnes as Sammy, a Crockett County deputy following the ambulance

- Tom Kennedy as traffic cop[4]

- Harry Lauter as radio operator[4]

- Ben Lessy as George the steward[4]

- Bobo Lewis as pilot's wife[4]

- Jerry Lewis as man driving over hat[4][6]

- Tyler McVey as a police radio voice (voice only)

- Barbara Pepper as waitress (scene deleted)[4]

- Eddie Rosson as miner's young son[9]

- Eddie Ryder as tower radioman[4]

- Jean Sewell as woman in migrant truck[9]

- Doodles Weaver as hardware store employee[4]

- Lennie Weinrib as a police radio voice, and as a fireman (voice only)[10]

Cast notes

[edit]According to Robert Davidson,[11] the role of Irwin originally was offered to Joe Besser, who was unable to participate when Sheldon Leonard and Danny Thomas could not give him time off from his co-starring role in The Joey Bishop Show.

Actress Eve Bruce filmed a scene as a showgirl who asks Benjy Benjamin and Ding Bell to help her apply suntan lotion. The scene was cut, and she is uncredited. Cliff Norton is listed in the opening credits but is not found in the film; Norton had a role as a detective who appears at the Rancho Conejo airport. King Donovan, playing an airport official, appeared in the Rancho Conejo scenes but was cut from the film. Don Knotts originally shot a second scene in which he tries to use a telephone in a diner. Also featured in the scene was Barbara Pepper.[5]

The first of the credited cast to die was ZaSu Pitts, who died on June 7, 1963, five months to the day before the film's release. With the death of Carl Reiner on June 29, 2020,[12] and Nicholas Georgiade on December 19, 2021,[13] Barrie Chase is the film's last surviving cast member, credited or otherwise. Mickey Rooney was the last living member of the main cast at the time of his death on April 6, 2014.[14]

Production

[edit]Background

[edit]In the early 1960s, screenwriter William Rose, then living in the United Kingdom, conceived the idea for a film (provisionally titled So Many Thieves, and later Something a Little Less Serious) about a comedic chase through Scotland. He sent an outline to Kramer, who agreed to produce and direct the film. The setting was shifted to America, and the working title changed to Where, but in America? then One Damn Thing After Another and then It's a Mad World, with Rose and Kramer adding additional "Mads" to the title as time progressed.[15] Kramer considered adding a fifth "mad" to the title before deciding it was redundant but noted in interviews that he later regretted it.

Although well known for serious films such as Inherit the Wind and Judgment at Nuremberg (both starring Tracy), Kramer set out to make the ultimate comedy film. Filmed in Ultra Panavision 70 and presented in Cinerama (becoming one of the early single-camera Cinerama features produced), Mad World had an all-star cast, with dozens of major comedy stars from all eras of cinema appearing in it. The film followed a Hollywood trend in the 1960s of producing "epic" films as a way of wooing audiences away from television and back to movie theaters. The film's theme music was written by Ernest Gold with lyrics by Mack David. Kramer hosted a roundtable (including extensive clips) on the film with stars Caesar, Hackett and Winters as part of a special The Comedians, Stanley Kramer's Reunion with the Great Comedy Artists of Our Time broadcast in 1974 as part of ABC's Wide World of Entertainment.[16] The last reported showing of the film on major network television in America was on ABC on July 16, 1979,[17] and before that, on CBS on May 16, 1978.[18]

Filming

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2015) |

The airport terminal scenes were filmed at the now-defunct Rancho Conejo Airport in Newbury Park, California, though the control tower shown was constructed only for filming. Other airplane sequences were filmed at the Sonoma County Airport north of Santa Rosa, California; at the Palm Springs International Airport; and in the skies above Thousand Oaks, California; Camarillo, California; and Orange County, California. In the Orange County scene, stuntman Frank Tallman flew a Beech model C-18S through a highway billboard advertising Coca-Cola. A communications mix-up resulted in the use of linen graphic sheets on the sign rather than paper, as planned. Linen, much tougher than paper, damaged the plane on impact.[citation needed] Tallman managed to fly it back to the airstrip, discovering that the leading edges of the wings had been smashed all the way back to the wing spars. Tallman considered that incident the closest he ever came to dying on film. (Both Tallman and Paul Mantz, Tallman's business partner and fellow flier on Mad World, eventually died in separate air crashes over a decade apart.)[19][20]

In another scene, Tallman flew the plane through an airplane hangar at the Sonoma County Airport in Santa Rosa.[21] Some scenes were filmed in San Diego.[22]

The fire escape and ladder miniature used in the final chase sequence is on display at the Hollywood Museum in Hollywood. Also, the Santa Rosita Fire Department's ladder truck was a 1960s Seagrave Fire Apparatus open-cab Mid-Mount Aerial Ladder.[23]

Production began on April 26, 1962, and expected to end by December 7, 1962, but took longer,[24] apparently conflicting with the notion that Tracy's trip down the zip line into the pet store on December 6, 1962, was the last scene filmed.[25] Veteran stuntman Carey Loftin was featured in the documentary, explaining some of the complexity as well as simplicity of stunts, such as the day he "kicked the bucket" as a stand-in for Durante.

Widescreen process

[edit]The film was promoted as the first film made in "one-projector" Cinerama. (The original Cinerama process required three separate cameras. The three processed reels were projected by three electronically synchronized projectors onto a huge curved screen.) It originally was planned for three-camera Cinerama, and some reports state that initial filming was done using three cameras but was abandoned. One-camera Cinerama could be Super Panavision 70 or Ultra Panavision 70, which was essentially the Super Panavision 70 process with anamorphic compression at the edges of the image to give a much wider aspect ratio.[citation needed] When projected by one projector, the expanded 70mm image filled the wide Cinerama screen. Ultra Panavision 70 was used to film It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World. Other films shot in Ultra Panavision 70 and released in Cinerama include The Greatest Story Ever Told, The Hallelujah Trail, Battle of the Bulge, and Khartoum. Super Panavision 70 films released in Cinerama include Grand Prix, 2001: A Space Odyssey, and Ice Station Zebra.[citation needed]

Animated credit sequence

[edit]Kramer's comedy was accentuated by many things, including the opening animated credits designed by Saul Bass. The film begins with mention of Spencer Tracy, then the "in alphabetical order" mention of nine of the main cast (Berle, Caesar, Hackett, Merman, Rooney, Shawn, Silvers, Terry-Thomas, Winters), followed by hands switching these nine names two to three times over. Animation continues with paper dolls and a wind-up toy world spinning with several men hanging on to it and finishing with a man opening a door to the globe and getting trampled by a mad crowd. One of the animators who helped with the sequence was future Peanuts animator Bill Melendez.[citation needed]

Release and reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]The film opened at the newly built Cinerama Dome in Los Angeles on November 7, 1963. The UK premiere was on December 2, 1963, at the Coliseum Cinerama Theatre in London's West End. Distinguished by the largest number of stars to appear in a film comedy, Mad World opened to acclaim from many critics[26] and tremendous box office receipts, becoming the third highest-grossing film of 1963, quickly establishing itself as one of the top 100 highest-grossing films of all time when adjusted for inflation, earning an estimated theatrical rental figure of $26 million. It grossed $46,332,858 domestically[27] and $60,000,000 worldwide,[2] on a budget of $9.4 million.[27] However, because costs were so high,[clarification needed] it earned a profit of only $1.25 million.[1] The film premiered with a runtime of 192 minutes, but after the premiere, United Artists shortened the runtime to 160 minutes for its general release. The original runtime was 202 minutes.

Critical response

[edit]Bosley Crowther of The New York Times wrote that the film "is everything, down to redundant, that its extravagant title suggests. It's a wonderfully crazy and colorful collection of 'chase' comedy, so crowded with plot and people that it almost splits the seams of its huge cinerama packing and its 3-hour-and-12-minute length."[28] Variety stated "There are a number of truly spectacular action sequences, and the stunts that have been performed seem incredible. The automobile capers are some of the most thrilling and daring on record, Mack Sennett notwithstanding." However, the review continued, "Certain pratfalls and sequences are unnecessarily overdone to the point where they begin to grow tedious ... but the plusses outweigh by far the minuses."[3]

Philip K. Scheuer of the Los Angeles Times wrote that the film "really bugged me ... the first few pratfalls have, perhaps their comic shock values. Thereafter the chase—and the homicidal mania—simply go on and on – countless cars are wrecked, a plane or two, an entire service station, the basement of a hardware store, fire escapes, a fire-engine tower. The only new idea, occurring well into the third hour, hinges on a surprise development in the character of a proud, plodding chief of detectives, played by Spencer Tracy—and even this proves disillusionment."[29]

Richard L. Coe of The Washington Post was mixed, writing "Yes, it is furious, fast and funny and it is also vast, vulgar and vexatious because Kramer has not given us one sympathetic character and because it is shown in Cinerama."[30] Paul Nelson wrote in Film Quarterly: "The film manages to stay on its feet for a little while and trundle self-importantly along, but it soon becomes painfully clear that its feet are flat and its wheels are square. Kramer lacks all the essentials of good comedy; he has few ideas, no cinematic or comic technique (the huge screen certainly didn't help him here: just one more technical burden), no sense of comic structure, and above all, no sense of pace."[31]

The film's great success inspired Kramer to direct and produce Guess Who's Coming to Dinner (also starring Tracy and also written by William Rose)[32] and The Secret of Santa Vittoria (also scored by Ernest Gold and co-written by Rose).[33] The movie was re-released in 1970 and earned an additional $2 million in rentals.[34]

The film holds a 69% approval rating on Rotten Tomatoes, based on 39 reviews, with an average score of 6.9/10. The consensus states: "It's long, frantic, and stuffed to the gills with comic actors and set pieces—and that's exactly its charm."[35]

Awards and honors

[edit]| Award | Category | Nominee(s) | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards | Best Cinematography – Color | Ernest Laszlo | Nominated | [36] |

| Best Film Editing | Frederic Knudtson, Robert C. Jones, and Gene Fowler Jr. | Nominated | ||

| Best Music Score – Substantially Original | Ernest Gold | Nominated | ||

| Best Song | "It's a Mad Mad Mad Mad World" Music by Ernest Gold; Lyrics by Mack David |

Nominated | ||

| Best Sound | Gordon E. Sawyer | Nominated | ||

| Best Sound Effects | Walter Elliott | Won | ||

| American Cinema Editors Awards | Best Edited Feature Film | Frederic Knudtson, Robert C. Jones, and Gene Fowler Jr. | Nominated | |

| Edgar Allan Poe Awards | Best Motion Picture Screenplay | William Rose and Tania Rose | Nominated | [37] |

| Golden Globe Awards | Best Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy | Nominated | [38] | |

| Best Actor in a Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy | Jonathan Winters | Nominated | ||

| Laurel Awards | Top Roadshow | Won | ||

| Top Song | "It's a Mad Mad Mad Mad World" Music by Ernest Gold; Lyrics by Mack David |

Won | ||

| New York Film Critics Circle Awards | Best Film | Nominated | [39] | |

The film is recognized by the American Film Institute in the following lists:

- 2000: AFI's 100 Years...100 Laughs – #40[40]

Home media

[edit]Existing footage is in the form of original 70 mm elements of the general release version (recent restored versions shown in revival screenings are derived from these elements). A 1991 VHS and LaserDisc from MGM/UA was an extended 183-minute version of the film, with most of the reinserted footage derived from elements stored in a Los Angeles warehouse about to be demolished.[41] According to a 2002 interview with master preservationist Robert A. Harris, this extended version is not a true representation of the original roadshow cut and included footage that was not meant to be shown in any existing version.[42]

A restoration effort was made by Harris in an attempt to bring the film back as close as possible to the original roadshow release. The project to go ahead with the massive restoration project would gain approval from Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (parent company of UA), although it did require a necessary budget for it to proceed.[42]

Released on January 21, 2014, originally as a two Blu-ray and three DVD set, the Criterion Collection release contains two versions of the film, a restored 4K digital film transfer of the 159-minute general release version and a new 197-minute high-definition digital transfer, reconstructed and restored by Harris using visual and audio material from the longer original "road-show" version not seen in over 50 years.[43][9] Some scenes have been returned to the film for the first time, and the Blu-ray features a 5.1 surround DTS-HD Master Audio soundtrack. It also features a new audio commentary from It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World aficionados Mark Evanier, Michael Schlesinger, and Paul Scrabo, a new documentary on the film's visual and sound effects, an excerpt from a 1974 talk show hosted by Stanley Kramer featuring Sid Caesar, Buddy Hackett, and Jonathan Winters, a press interview from 1963 featuring Kramer and cast members, excerpts about the film's influence taken from the 2000 American Film Institute program 100 Years...100 Laughs, a two-part 1963 episode of Canadian TV program Telescope that follows the film's press junket and premiere, a segment from the 2012 special The Last 70mm Film Festival featuring surviving Mad World cast and crew members hosted by Billy Crystal, a selection of Stan Freberg's original TV and radio ads for the film with a new introduction by Freberg, trailers and radio spots from the 1960s/70s, and a booklet featuring an essay by film critic Lou Lumenick with new illustrations by cartoonist Jack Davis, along with a map of the shooting locations by artist Dave Woodman.[9]

Soundtrack

[edit]- "It's a Mad Mad Mad Mad World" (1963) – Music by Ernest Gold – Lyrics by Mack David

- "You Satisfy My Soul" (1963) – Music by Ernest Gold – Lyrics by Mack David – Played by The Four Mads – Sung by The Shirelles

- "Thirty-One Flavors" (1963) – Music by Ernest Gold – Lyrics by Mack David – Played by The Four Mads – Sung by The Shirelles

Influence

[edit]Films having a comedic search for money with an ensemble cast modeled after It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World include Unbelievable Adventures of Italians in Russia (1974),[44] Scavenger Hunt (1979),[45] Million Dollar Mystery (1987)[46] and Rat Race (2001).[47][48] There are similar Indian films, such as Journey Bombay to Goa: Laughter Unlimited (2007), Dhamaal (2007), Mast Maja Maadi (2008) and Total Dhamaal (2019).[49][50][51][52]

Abandoned sequel

[edit]According to Paul Scrabo, Kramer began thinking about his success with Mad World during the 1970s, and considered bringing back many former cast members for a proposed film titled The Sheiks of Araby. William Rose was set to write the screenplay. Years later, Kramer announced a possible Mad World sequel, which was to be titled It's a Funny, Funny World, but this has never been made.[53]

Possible Remake

[edit]In June 2024 during an interview with Entertainment Tonight, Eddie Murphy announced that he completed a script with Martin Lawrence for a remake, like the original would feature comedians from the past 30 years. [54]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Balio, Tino (2009). United Artists: The Company That Changed the Film Industry. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 146. ISBN 978-0299230142. Archived from the original on May 20, 2021. Retrieved October 18, 2020.

- ^ a b Box Office Information for It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World. Archived July 14, 2014, at the Wayback Machine The Numbers. Retrieved September 5, 2013.

- ^ a b "It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World". Variety. November 6, 1963. p. 6. Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved March 8, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s "It's A Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World Cast & Crew". TV Guide. Archived from the original on November 10, 2016. Retrieved March 19, 2020.

- ^ a b Hall, Phil (May 25, 2016). In Search of Lost Films. BearManor Media. pp. 148–150. ISBN 978-1593939380. Archived from the original on May 20, 2021. Retrieved October 18, 2020.

- ^ a b "It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Archived from the original on May 23, 2019. Retrieved March 19, 2020. "Virtually every lead, supporting, and bit part in the picture is filled by a well-known comic actor: the laughspinning lineup also includes Carl Reiner, Terry-Thomas, Arnold Stang, Buster Keaton, Jack Benny, Jerry Lewis, and The Three Stooges, who get one of the picture's biggest laughs by standing stock still and uttering not a word."

- ^ "John Clarke". soapcentral.com. Archived from the original on April 10, 2016. Retrieved April 11, 2017.

- ^ Walker, Brent E. (2009). "Minta Dufee". Mack Sennett's Fun Factory. McFarland & Co. p. 500. ISBN 978-0786436101. Archived from the original on May 20, 2021. Retrieved October 18, 2020.

- ^ a b c d "It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (1963)". The Criterion Collection. Archived from the original on April 1, 2019. Retrieved October 25, 2013.

- ^ McLellan, Dennis (July 2, 2006). "Lennie Weinrib, 71; Actor Voiced H.R. Pufnstuf". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 19, 2020. Retrieved March 19, 2020.

... and did a variety of voices for the movie comedy 'It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World.'

- ^ Davidson, Robert. "It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, Cast Members". The Three Stooges Online Filmography. Archived from the original on February 12, 2019. Retrieved March 10, 2012.

- ^ Stewart, Mike (June 30, 2020). "Carl Reiner, Beloved Creator of 'Dick Van Dyke Show,' Dies". After Hours Youngstown. Archived from the original on May 20, 2021. Retrieved August 23, 2020.

- ^ Mike Barnes (December 22, 2021). "Nicholas Georgiade, One of Eliot Ness' Agents on 'The Untouchables,' Dies at 88". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved December 24, 2021.

- ^ McCartney, Anthony (April 7, 2014). "Iconic Actor Mickey Rooney Dies at 93". The Ledger. Archived from the original on May 20, 2021. Retrieved August 23, 2020.

- ^ "Behind the Mad-ness – It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World". Urban Cinephile. July 1, 2004. Archived from the original on November 18, 2018. Retrieved September 2, 2009.

- ^ "Stanley Kramer Collection". UCLA Film & Television Archive. Archived from the original on June 11, 2019. Retrieved March 8, 2020.

- ^ "'Mad World' Repeats". The Daily Item. Sumter, South Carolina. July 16, 1979. p. 6B. Archived from the original on May 20, 2021. Retrieved January 16, 2016.

- ^ "Television". Jet. Johnson Publishing Company. May 18, 1978. p. 66. Archived from the original on May 20, 2021. Retrieved March 8, 2020.

- ^ Malnic, Eric; Sahagun, Louis (February 22, 1989). "Pilot Told of Bad Weather, FAA Says of Crash Killing 10". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 29, 2015. Retrieved July 20, 2017.

- ^ Holden, Henry M. (September 1, 2004). "Paul Mantz and the Last Flight of the Phoenix". Airport Journals. Archived from the original on July 30, 2017. Retrieved July 20, 2017.

- ^ a b "Museum History". Pacific Coast Air Museum. Archived from the original on January 31, 2020. Retrieved October 9, 2014.

- ^ "FILMING SAN DIEGO | San Diego History Center". San Diego History. July 10, 2012. Archived from the original on July 10, 2012. Retrieved December 9, 2022.

- ^ "Collections & Exhibits". Hollywood Museum. Archived from the original on September 15, 2008.

- ^ "It's A Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World production log". December 19, 1962. Archived from the original on August 3, 2016. Retrieved March 9, 2013.

- ^ "Modern photos of locations in 1963 movie 'It's A Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World'". Archived from the original on October 11, 2010. Retrieved May 31, 2010.

- ^ Mersereau, Don (November 11, 1963). "It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, United Artists (Review)". Boxoffice.

- ^ a b Box Office Information for It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World. Archived July 14, 2019, at the Wayback Machine Box Office Mojo. Retrieved September 5, 2013.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (November 19, 1963). "Screen: Wild Comedy About the Pursuit of Money". Archived May 27, 2019, at the Wayback Machine The New York Times. 46.

- ^ Scheuer, Philip K. (November 5, 1963). "'It's a Mad World' Challenge to Sanity". Los Angeles Times. Part IV, p. 11.

- ^ Coe, Richard L. (February 20, 1964). "'Mad World' Is a Comedy?" The Washington Post. A28.

- ^ Nelson, Paul (Spring 1964). "Film Reviews: It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World". Film Quarterly. Vol. XVII, No. 3. p. 42.

- ^ "Guess Who's Coming To Dinner (1967)". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on February 4, 2014. Retrieved April 29, 2014.

- ^ "The Secret of Santa Vittoria (1969)". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on May 2, 2014. Retrieved April 29, 2014.

- ^ "Big Rental Films of 1970", Variety, January 6, 1971 p 11

- ^ Film reviews for It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World. Archived September 16, 2020(Date mismatch), at the Wayback Machine Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved September 5, 2013.

- ^ "The 36th Academy Awards (1964) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on November 2, 2017. Retrieved August 23, 2011.

- ^ "Category List – Best Motion Picture". Edgar Awards. Retrieved October 28, 2024.

- ^ "It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World". Golden Globe Awards. Archived from the original on August 2, 2017. Retrieved August 1, 2017.

- ^ Weiler, A. H. (December 31, 1963). "Film Critics Vote 'Tom Jones' Best of Year; Finney Named Top Actor for Title Role --'Hud' Honored Finney in 3d Film". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 19, 2020. Retrieved December 29, 2017.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Laughs" (PDF). American Film Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 16, 2013. Retrieved August 6, 2016.

- ^ Andrews, Robert M. (August 26, 1991). "It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad Obsession: Movies: An aide to Rep. Norman Mineta carries on a lonely crusade to locate all of the 56 minutes lopped from Stanley Kramer's 1963 classic". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Archived from the original on February 20, 2017. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- ^ a b Epstein, Ron (June 2, 2002). "It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World Restoration". Home Theater Forum. Archived from the original on April 3, 2002. Retrieved May 19, 2013.

- ^ "It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World as 197-Min Cut". Movie-Censorship. October 25, 2013. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved October 25, 2013.

- ^ Olga Afanasyeva (2016). Eldar Ryazanov. Irony of Fate, Or... // Adventures of Italians in Russia and Russians in Italy. — Moscow: Aegitas. 240 pages ISBN 978-5-906789-26-6

- ^ Michaels, Bob (December 29, 1979). "Entertainment Tough to Find In 'Scavenger Hunt' Movie". Palm Beach Post.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (June 12, 1987). "Film: 'Million Dollary Mystery'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on November 5, 2017. Retrieved August 23, 2020.

- ^ Silverman, Stephen M. (August 27, 2001). "The Joker is Wild: Mad at 'Rat Race'". People.com. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved August 23, 2020.

- ^ George, Vijay (May 13, 2011). "Exploring genres". The Hindu. Chennai. Archived from the original on January 2, 2014.

- ^ Roy, Priyanka (February 22, 2019). "Don't waste your paisa on Total Dhamaal". The Telegraph. Kolkata. Archived from the original on April 20, 2020. Retrieved March 8, 2020.

- ^ Kokra, Sonali (February 24, 2019). "Six reasons why 'Total Dhamaal' is sexist, derogatory and a waste of good talent". The National. Abu Dhabi. Archived from the original on October 23, 2019. Retrieved March 8, 2020.

- ^ Sen, Raja (February 22, 2019). "Total Dhamaal movie review: Yet another Ajay Devgn atrocity. 1 star". Hindustan Times. New Delhi. Archived from the original on October 23, 2019. Retrieved March 8, 2020.

- ^ Ashraf, Syed Firdaus. "Dhamaal movie!". Rediff.com. Archived from the original on October 23, 2019. Retrieved October 23, 2019.

- ^ Beck, Marilyn; Smith, Stacy Jenel (June 20, 1991). "Stanley steaming with funny ideas". New York Daily News.

- ^ "Eddie Murphy Teases His Upcoming Project with Martin Lawrence".

External links

[edit]- It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World at IMDb

- It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World at the TCM Movie Database

- It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World at AllMovie

- It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World at Rotten Tomatoes

- "It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World: Nothing Succeeds Like Excess," an essay by Lou Lumenick at the Criterion Collection

- Article documenting Robert Harris' attempt to restore It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World at the Wayback Machine (archived April 3, 2002)

- Writer Mark Evanier discusses his favorite movie

- Still a 'Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World'?

- 1963 films

- 1963 comedy films

- American chase films

- American epic films

- American comedy road movies

- 1960s English-language films

- Films scored by Ernest Gold

- Films directed by Stanley Kramer

- Films produced by Stanley Kramer

- Films set in California

- Films shot in California

- Films that won the Best Sound Editing Academy Award

- Films about treasure hunting

- United Artists films

- 1960s American films

- Films shot in San Diego

- 1960s comedy road movies

- Comedy epic films

- Films using stop-motion animation