Emerald Tablet

The Emerald Tablet, the Smaragdine Table, or the Tabula Smaragdina[a] is a compact and cryptic Hermetic text.[1] It was a highly regarded foundational text for many Islamic and European alchemists.[2] Though attributed to the legendary Hellenistic figure Hermes Trismegistus, the text of the Emerald Tablet first appears in a number of early medieval Arabic sources, the oldest of which dates to the late eighth or early ninth century. It was translated into Latin several times in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Numerous interpretations and commentaries followed.

Medieval and early modern alchemists associated the Emerald Tablet with the creation of the philosophers' stone and the artificial production of gold.[3]

It has also been popular with nineteenth- and twentieth-century occultists and esotericists, among whom the expression "as above, so below" (a modern paraphrase of the second verse of the Tablet) has become an often cited motto.

Tis true without lying, certain and most true. That which is below is like that which is above and that which is above is like that which is below to do the miracle of one only thing. And as all things have been and arose from one by the mediation of one: so all things have their birth from this one thing by adaptation. The Sun is its father, the moon its mother, the wind hath carried it in its belly, the earth is its nurse. The father of all perfection in the whole world is here. Its force or power is entire if it be converted into earth. Separate thou the earth from the fire, the subtle from the gross sweetly with great industry. It ascends from the earth to the heaven and again it descends to the earth and receives the force of things superior and inferior. By this means you shall have the glory of the whole world and thereby all obscurity shall fly from you. Its force is above all force, for it vanquishes every subtle thing and penetrates every solid thing. So was the world created. From this are and do come admirable adaptations where of the means is here in this. Hence I am called Hermes Trismegist, having the three parts of the philosophy of the whole world. That which I have said of the operation of the Sun is accomplished and ended.

— English translation of the Emerald Tablet by Isaac Newton[4]

Background

[edit]Beginning from the 2nd century BC onwards, Greek texts attributed to Hermes Trismegistus, a syncretic combination of the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth, appeared in Greco-Roman Egypt. These texts, known as the Hermetica, are a heterogeneous collection of works that in the modern day are commonly subdivided into two groups: the technical Hermetica, comprising astrological, medico-botanical, alchemical, and magical writings; and the religio-philosophical Hermetica, comprising mystical-philosophical writings.[5]

These Greek pseudepigraphal texts found receptions, translations and imitations in Latin, Syriac, Coptic, Armenian, and Middle Persian prior to the emergence of Islam and the Arab conquests in the 630s. These developments brought about various Arabic-speaking empires in which a new group of Arabic-speaking intellectuals emerged. These scholars received and translated the before-mentioned wealth of texts and also began producing Hermetica of their own.[6]

History

[edit]Until the early 20th century, only Latin versions of the Emerald Tablet were known, with the oldest dating back to the 12th century. The first Arabic versions were rediscovered by the English historian of science E.J. Holmyard (1891-1959) and the German orientalist Julius Ruska (1867-1949).[7]

Arabic versions

[edit]

The Emerald Tablet has been found in various ancient Arabic works in different versions. The oldest version is found as an appendix in a treatise believed to have been composed in the 9th century,[8] known as the Book of the Secret of Creation, Kitâb sirr al-Halîka in Arabic. This text presents itself as a translation of Apollonius of Tyana, under his Arabic name Balînûs.[9] Although no Greek manuscript has been found, it is plausible that an original Greek text existed.[10] The attribution to Apollonius, though false (pseudonymous), is common in medieval Arabic texts on magic, astrology, and alchemy.

The introduction to the Book of the Secret of Creation is a narrative that explains, among other things, that "all things are composed of four elemental principles: heat, cold, moisture, and dryness" (the four qualities of Aristotle), and their combinations account for the "relations of sympathy and antipathy between beings." Balînûs, "master of talismans and wonders," enters a crypt beneath the statue of Hermes Trismegistus and finds the emerald tablet in the hands of a seated old man, along with a book. The core of the work is primarily an alchemical treatise that introduces for the first time the idea that all metals are formed from sulfur and mercury, a fundamental theory of alchemy in the Middle Ages.[11] The text of the Emerald Tablet appears last, as an appendix.[12] It has long been debated whether it is an extraneous piece, solely cosmogonic in nature, or if it is an integral part of the rest of the work, in which case it has an alchemical significance from the outset.[13] Recently, it has been suggested that it is actually a text of talismanic magic and that the confusion arises from a mistranslation from Arabic to Latin.[14]

Emerald is the stone traditionally associated with Hermes, while mercury is his metal. Mars is associated with red stones and iron, and Saturn is associated with black stones and lead.[15] In antiquity, Greeks and Egyptians referred to various green-coloured minerals (green jasper and even green granite) as emerald, and in the Middle Ages, this also applied to objects made of coloured glass, such as the "Emerald Tablet" of the Visigothic kings [16] or the Sacro Catino of Genoa (a dish seized by the Crusaders during the sack of Caesarea in 1011, which was believed to have been offered by the Queen of Sheba to Solomon and used during the Last Supper).[17]

This version of the Emerald Tablet is also found in the Kitab Ustuqus al-Uss al-Thani (Elementary Book of the Foundation) attributed to the 8th-century alchemist Jâbir ibn Hayyân, known in Europe by the latinized name Geber.

Another version is found in an eclectic book from the 10th century, the Secretum Secretorum (Secret of Secrets, Sirr al-asrâr), which presents itself as a pseudo-letter from Aristotle to Alexander the Great during the conquest of Persia. It discusses politics, morality, physiognomy, astrology, alchemy, medicine, and more. The text is also attributed to Hermes but lacks the narrative of the tablet's discovery.

The literary theme of the discovery of Hermes' hidden wisdom can be found in other Arabic texts from around the 10th century. For example, in the Book of Crates, while praying in the temple of Serapis, Crates, a Greek philosopher, has a vision of "an old man, the most beautiful of men, seated in a chair. He was dressed in white garments and held a tablet on the chair, upon which was placed a book [...]. When I asked who this old man was, I was told, 'He is Hermes Trismegistus, and the book before him is one of those that contain the explanation of the secrets he has hidden from men.'".[18] A similar account can be found in the Latin text known as Tabula Chemica by Senior Zadith, the latinized name of the alchemist Ibn Umail, in which a stone table rests on the knees of Hermes Trismegistus in the secret chamber of a pyramid. Here, the table is not inscribed with text but with "hieroglyphic" symbols.[19]

Early Latin versions and medieval commentaries

[edit]Latin versions

[edit]The Book of the Secret of Creation was translated into Latin (Liber de secretis naturae) in c. 1145–1151 by Hugo of Santalla.[20] This text does not appear to have been widely circulated.[21]

The Secret of Secrets (Secretum Secretorum) was translated into Latin in an abridged 188 lines long medical excerpt by John of Seville around 1140. The first full Latin translation of the text was prepared by Philip of Tripoli around a century later. This work has been called "the most popular book of the Latin Middle Ages".[22]

A third Latin version can be found in an alchemical treatise dating probably from the 12th century (although no manuscripts are known before the 13th or 14th century), the Liber Hermetis de alchimia (Book of Alchemy of Hermes). This version, known as the "vulgate," is the most widespread.[23] The translator of this version did not understand the Arabic word tilasm, which means talisman, and therefore merely transcribed it into Latin as telesmus or telesmum. This accidental neologism was variously interpreted by commentators, thereby becoming one of the most distinctive, yet vague, terms of alchemy.[24]

Commentaries

[edit]In his 1143 treatise, De essentiis, Herman of Carinthia is one of a few European 12th century scholars to cite the Emerald Tablet. In this text he also recalls the story of the tablet's discovery under a statue of Hermes in a cave from the Book of the Secret of Creation. Carinthia was a friend of Robert of Chester, who in 1144 translated the Liber de compositione alchimiae, which is generally considered to be the first Latin translation of an Arabic treatise on alchemy.[25]

An anonymous 12th-century commentator tried to explain the neologism telesmus in the phrase Latin: Pater omnis telesmi, lit. 'Father of all telesms' by claiming it is synonymous with Latin: Pater omnis secreti, lit. 'Father of everything secret'. The translator followed this claim with the assertion that a superior kind of divination among the Arabs is called Latin: Thelesmus. In subsequent commentaries of the Emerald Tablet only the meaning of secret was retained.[26]

Around 1275–1280, Roger Bacon translated and commented on the Secret of Secrets,[27] and through a completely alchemical interpretation of the Emerald Tablet, made it an allegorical summary of the Great Work.[28]

The most well-known commentary is that of Hortulanus, an alchemist about whom very little is known, in the first half of the 14th century:

I, Hortulanus, that is to say, gardener... I have wanted to write a clear explanation and certain explanation of the words of Hermes, father of philosophers, although they are obscure, and to sincerely explain the entire practice of the true work. And certainly, it is of no use for philosophers to want to hide the science in their writings when the doctrine of the Holy Spirit operates.

This text is in line with the symbolic alchemy that developed in the 14th century, particularly with the texts attributed to the Catalan physician Arnau de Vilanova, which establish an allegorical comparison between Christian mysteries and alchemical operations. In Ortolanus' commentary, devoid of practical considerations, the Great Work is an imitation of the divine creation of the world from chaos: "And as all things have been and arose from one by the mediation of one: so all things have their birth from this one thing by adaptation." The sun and the moon represent alchemical gold and silver.[29] Hortulanus interprets "telesma" as "secret" or "treasure": "It is written afterward: 'The father of all telesma of the world is here,' that is to say: in the work of the stone is found the final path. And note that the philosopher calls the operation 'father of all telesma,' that is to say, of all the secret or all the treasure of the entire world, that is to say, of every stone discovered in this world.".[24]

Starting from 1420, extensive excerpts are included in an illuminated text, the Aurora consurgens, which is one of the earliest cycles of alchemical symbols. One of the illustrations shows the discovery of Hermes' table in a temple surmounted by Sagittarius eagles (representing the volatile elements). This motif is frequently used in Renaissance prints and is the visual expression of the myth of the rediscovery of ancient knowledge—the transmission of this knowledge, in the form of hieroglyphic pictograms, allows it to escape the distortions of human and verbal interpretation.[30]

From the Renaissance to the Enlightenment

[edit]

During the Renaissance, the idea that Hermes Trismegistus was the founder of alchemy gained prominence, and at the same time, the legend of the discovery evolved and intertwined with biblical accounts.[citation needed] This is particularly the case in the late 15th century in the Livre de la philosophie naturelle des métaux by the pseudo-Bernard of Treviso:[31] "The first inventor of this Art was Hermes Trismegistus, for he knew all three natural philosophies, namely Mineral, Vegetable, and Animal."[citation needed] This text influenced a discovery legend claiming the tablet to have been discovered after the Biblical Flood in Hebron valley which is connected with the image of the "Emblem of the Smaragdine Tablet" in the 1599 text Aureum Vellus.[32]

It further evolves with Jérôme Torella in his book on astrology, Opus Praeclarum de imaginibus astrologicis (Valence, 1496), in which it is Alexander the Great who discovers a Tabula Zaradi in Hermes' tomb while travelling to the Oracle of Amun in Egypt. This story is repeated by Michael Maier, physician and counselor to the "alchemical emperor" Rudolf II, in his symbola aureae mensae (Frankfurt, 1617), referring to a Liber de Secretis chymicis attributed to Albertus Magnus.[33] In the same year, he publishes the famous Atalanta Fugiens (Fleeing Atalanta), illustrated by Theodor de Bry with fifty alchemical emblems, each accompanied by a poem, a musical fugue, and alchemical and mythological explanations. The first two emblems depict a passage from the Emerald Tablet: "the wind has carried it in its belly; the earth is its nurse," and the explanatory text begins with "Hermes, the most diligent explorer of all natural secrets, describes in his Emerald Tablet the work of nature, albeit briefly and accurately."[34]

The first printed edition appears in 1541 in the De alchemia published by Johann Petreius and edited by a certain Chrysogonus Polydorus, who is likely a pseudonym for the Lutheran theologian Andreas Osiander (Osiander also edited Copernicus' On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres in 1543, published by the same printer). This version is known as the "vulgate" version and includes the commentary by Hortulanus.

In 1583, a commentary by Gerard Dorn is published in Frankfurt by Christoph Corvinus. In De Luce naturae physica, this disciple of Paracelsus makes a detailed parallel between the Table and the first chapter of the Genesis attributed to Moses.

In the 15th and 16th centuries, verse versions appear, including an anonymous sonnet revised by the alchemical poet Clovis Hesteau de Nuysement in his work Traittez de l'harmonie, et constitution generalle du vray sel, secret des Philosophes, & de l'esprit universel du monde (1621):

C'est un point aſſuré plein d'admiration, |

It is a certain point full of admiration, |

| —Hesteau 1639, p. 10. | —literal translation |

However, from the beginning of the 17th century onward, a number of authors challenge the attribution of the Emerald Tablet to Hermes Trismegistus and, through it, attack antiquity and the validity of alchemy. First among them is a "repentant" alchemist, the Lorraine physician Nicolas Guibert, in 1603. But it is the Jesuit scholar and linguist Athanasius Kircher who launches the strongest attack in his monumental work Oedipus Aegyptiacus (Rome, 1652–1653). He notes that no texts speak of the Emerald Tablet before the Middle Ages and that its discovery by Alexander the Great is not mentioned in any ancient testimonies. By comparing the vocabulary used with that of the Corpus Hermeticum (which had been proven by Isaac Casaubon in 1614 to date only from the 2nd or 3rd century AD), he affirms that the Emerald Tablet is a forgery by a medieval alchemist. As for the alchemical teaching of the Emerald Tablet, it is not limited to the philosopher's stone and the transmutation of metals but concerns "the deepest substance of each thing," the alchemists' quintessence. From another perspective, Wilhelm Christoph Kriegsmann publishes in 1657 a commentary in which he tries to demonstrate, using the linguistic methods of the time, that the Emerald Tablet was not originally written in Egyptian but in Phoenician.

He continues his studies of ancient texts and in 1684 argues that Hermes Trismegistus is not the Egyptian Thoth but the Taaut of the Phoenicians, who is also the founder of the Germanic people under the name of the god Tuisto, mentioned by Tacitus.[35]

In the meantime, Kircher's conclusions are debated by the Danish alchemist Ole Borch in his De ortu et progressu Chemiae (1668), in which he attempts to separate the hermetic texts between the late writings and those truly attributable to the ancient Egyptian Hermes, among which he inclines to classify the Emerald Tablet. The discussions continue, and the treatises of Ole Borch and Kriegsmann are reprinted in the compilation Bibliotheca Chemica Curiosa (1702) by the Swiss physician Jean-Jacques Manget. Although the Emerald Tablet is still translated and commented upon by Isaac Newton,[36] alchemy gradually loses all scientific credibility during the 18th century with the advent of modern chemistry and the work of Lavoisier.

The emblem of the Tabula Smaragdina Hermetis

[edit]

From the late 16th century onwards, the Emerald Tablet is often accompanied by a symbolic figure called the Tabula Smaragdina Hermetis.

This figure is surrounded by an acrostic in Latin: Visita interiora terrae rectificando invenies occultum lapidem, lit. 'visit the interior of the earth and by rectifying you will find the hidden stone' whose seven initials form the word Old French: vitriol, lit. 'sulphuric acid'. At the top, the sun and moon pour into a cup above the symbol of mercury. Around the mercurial cup are the four other planets, representing the classic association between the seven planets and the seven metals: Sol/Gold, Luna/Silver, Mercury/Quicksilver, Jupiter/Tin, Mars/Iron, Venus/Copper, Saturn/Lead. It is unclear if the image was originally drawn using colours or not. The ones which do contain them are coloured as follows gold-sol-visita, silver-luna-interiora, grey-mercury-terrae, blue-tin-rectificando, red-iron-invenies, green-copper, black-lead-lapidem. In the center, there are a ring and a globus cruciger, and at the bottom, there are the spheres of the sky and the earth. Three charges represent, according to the poem, the three principles (tria prima) of the alchemical theory of Paracelsus: Eagle/Mercury/Spirit, Lion/Sulfur/Soul, and Star/Salt/Body. Finally, two Schwurhands accompany the picture attesting its creator's veracity.[37]

The oldest known reproduction is a copy dated 1588-89 of a manuscript that was circulating anonymously at the time and was likely written in the second half of the 16th century by a German Paracelsian. The image was accompanied by a didactic alchemical poem in German titled Du secret des sages,[38] probably by the same author. The poem explains the symbolism in relation to the Great Work and the classical goals of alchemy: wealth, health, and long life.[39] Initially, it was only accompanied by the text of the Emerald Tablet as a secondary element. However, in printed reproductions during the 17th century, the accompanying poem disappeared, and the emblem became known as the Tabula Smaragdina Hermetis, the symbol or graphical representation of the Emerald Tablet, as ancient as the tablet itself.

For example, in 1733, according to the alchemist Ehrd de Naxagoras (Supplementum Aurei Velleris), a "precious emerald plate" engraved with inscriptions and the symbol was made upon Hermes' death and found in the valley of Ebron by a woman named Zora.[33] This emblem is placed within the mysterious tradition of Egyptian hieroglyphs and the idea of Platonists and alchemists during the Renaissance that the "deepest secrets of nature could only be expressed appropriately through an obscure and veiled mode of representation".[40]

19th–20th century: from occultism to esotericism and surrealism

[edit]Alchemy and its alleged "foundational text" continue to interest occultists. This is the case with the mage Éliphas Lévi: "Nothing surpasses and nothing equals as a summary of all the doctrines of the old world the few sentences engraved on a precious stone by Hermes and known as the 'emerald tablet'... it is all of magic on a single page.".[41] It also applies to the "curious figure"[42] of the German Gottlieb Latz, who self-published a monumental work Die Alchemie in 1869,[43] as well as the theosophist Helena Blavatsky[44] and the perennialist Titus Burckhardt.[45]

At the beginning of the 20th century, alchemical thought resonated with the surrealists,[46] and André Breton incorporated the main axiom of the Emerald Tablet into the Second Manifesto of Surrealism (1930): "Everything leads us to believe that there exists a certain point of the spirit from which life and death, the real and the imaginary, the past and the future, the communicable and the incommunicable, the high and the low, cease to be perceived as contradictory. However, in vain would one seek any motive other than the hope for the determination of this point in surrealist activity.".[47] Although some commentators mainly see the influence of the philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel in this statement,[48] Hegel's philosophy itself was influenced by Jakob Böhme.[49]

Textual history

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Hermeticism |

|---|

|

Like most other works attributed to Hermes Trismegistus, the Emerald Tablet is very hard to date with any precision, but generally belongs to the late antique period (between c. 200 and c. 800).[50] The oldest known source of the text is the Sirr al-khalīqa wa-ṣanʿat al-ṭabīʿa (The Secret of Creation and the Art of Nature, also known as the Kitāb al-ʿilal or The Book of Causes), an encyclopaedic work on natural philosophy falsely attributed to Apollonius of Tyana (c. 15–100, Arabic: Balīnūs or Balīnās).[51] This book was compiled in Arabic in the late eighth or early ninth century,[52] but it was most likely based on (much) older Greek and/or Syriac sources.[53] In the frame story of the Sirr al-khalīqa, Balīnūs tells his readers that he discovered the text in a vault below a statue of Hermes in Tyana, and that, inside the vault, an old corpse on a golden throne held the emerald tablet.[54]

Slightly different versions of the Emerald Tablet also appear in the Kitāb Usṭuqus al-uss al-thānī (The Second Book of the Element of the Foundation, c. 850–950) attributed to Jabir ibn Hayyan,[55] in the longer version of the Sirr al-asrār (The Secret of Secrets, a tenth-century compilation of earlier works that was falsely attributed to Aristotle),[56] and in the Egyptian alchemist Muhammed ibn Umail al-Tamimi's (ca. 900 – 960) Kitāb al-māʾ al-waraqī wa-l-arḍ al-najmiyya (Book of the Silvery Water and the Starry Earth).[57]

The Emerald Tablet was translated into Latin in the twelfth century by Hugo of Santalla as part of his translation of the Sirr al-khalīqa.[58] It was again translated into Latin along with the thirteenth-century translation of the longer version of the pseudo-Aristotelian Sirr al-asrār (Latin: Secretum secretorum).[59] However, the Latin translation which formed the basis for all later versions (the so-called 'Vulgate') was originally part of an anonymous compilation of alchemical commentaries on the Emerald Tablet variously called Liber Hermetis de alchimia, Liber dabessi, or Liber rebis (first half of the twelfth century).[60]

Arabic versions of the tablet text

[edit]From pseudo-Apollonius of Tyana's Sirr al-khalīqa (c. 750–850)

[edit]The earliest known version of the Emerald Tablet on which all later versions were based is found in pseudo-Apollonius of Tyana's Sirr al-khalīqa wa-ṣanʿat al-ṭabīʿa (The Secret of Creation and the Art of Nature).[61]

حقٌّ لا شكَّ فيه صَحيح،

إنّ الأعلى من الأسفل والأسفل من الأعلى،

عمل العجائب من واحد كما كانت الأشياء كلّها من واحد بتدبير واحد،

أبوه الشمس، أُمّه القمر،

حملته الريح في بطنها، غذته الأرض،

أبو الطِّلسمات، خازن العجائب، كامل القوى،

نار صارت أرضاً ٱعزِل الأرض من النار،

اللطيف أكرم من الغليظ،

برِفق وحُكم يصعد من الأرض إلى السماء وينزل إلى الأرض من السماء،

وفيه قُوّة الأعلى والأسفل،

لأنّ معه نور الأنوار فلذلك تهرب منه الظُّلمة،

قُوّة القوى

يغلب كلّ شيء لطيف، يدخل في كلّ شيء غليظ،

على تكوين العالَم الأكبر تكوّن العمل،

فهذا فَخْرِي ولذلك سُمّيتُ هرمس المثلَّث بالحكمة.(a) truth; no doubt [it] is true

indeed, the uppermost is from the lowermost and the lowermost is from the uppermost,

[it] worked the wonders from one, (just) as all things come from one by means of one plan/with one considered act,

[its] father is the sun, [its] mother is the moon,

the wind carried [it] in her womb, the earth fed [it],

father of talismans, keeper of wonders, perfect in power,

fire became earth, separate [imperative directed at a male recipient] the earth from the fire,

the soft/delicate/gentle/subtle is more noble than the crude/rough/unintelligent/gross,

with gentle-being and wisdom [it] ascends from the earth to the heaven and descends to the earth from the heaven,

and in [it] is the power of the uppermost and the lowermost,

since with [it] is the light of lights therefore the darkness escapes (away) from [it],

power of powers

it prevails over everything soft/delicate/gentle/subtle, enters into everything crude/rough/unintelligent/gross,

against the creation of the macrocosm the work was created,

this is my renown and therefore I am named Hermes the threefold with the wisdom.—Weisser 1979, pp. 524–525. —literal translation; multiple possible meanings have been given in italic; since Arabic only has two grammatical genders and the translated pronoun is grammatically male, [it/its] can also be translated as [he/his/him].[62]

From the Kitāb Usṭuqus al-uss al-thānī (ca. 850–950) attributed to Jabir ibn Hayyan

[edit]A somewhat shorter version is quoted in the Kitāb Usṭuqus al-uss al-thānī (The Second Book of the Element of the Foundation) attributed to Jabir ibn Hayyan.[55] Lines 6, 8, and 11–15 from the version in the Sirr al-khalīqa are missing, while other parts seem to be corrupt.[63] Jabir's version was translated by Eric J. Holmyard:

حقا يقينا لا شك فيه |

Truth! Certainty! That in which there is no doubt! |

| —Zirnis 1979, p. 90. | —Holmyard 1923. |

From the pseudo-Aristotelian Sirr al-asrār (tenth century)

[edit]A still later version is found in the pseudo-Aristotelian Sirr al-asrār (Secret of Secrets, tenth century).[64]

حقا يقينا لا شك فيه

أن الأسفل من الأعلى والأعلى من الأسفل

عمل العجائب من واحد بتدبير واحد كما نشأت الأشياء من جوهر واحد

أبوه الشمس وأمه القمر

حملته الريح في بطنها، وغذته الأرض بلبانها

أبو الطلسمات، خازن العجائب، كامل القوى

فان صارت أرضا اعزل الأرض من النار اللطيف

أكرم من الغليظ

برفق وحكمة تصعد من الأرض إلى السماء وتهبط إلى الأرض

فتقبل قوة الأعلى والأسفل

لأن معك نور الأنوار فلهذا تهرب عنك الظلمة

قوة القوى

تغلب كل شيء لطيف يدخل على كل شيء كثيف

على تقدير العالم الأكبر

هذا فخري ولهذا سمّيت هرمس المثلّث بالحكمة اللدنية[65]

Medieval Latin versions of the tablet text

[edit]From the Latin translation of pseudo-Apollonius of Tyana's Sirr al-khalīqa (De secretis nature)

[edit]The tablet was translated into Latin in c. 1145–1151 by Hugo of Santalla as part of his translation of the Sirr al-khalīqa (The Secret of Creation, original Arabic above).[66]

Superiora de inferioribus, inferiora de superioribus,

prodigiorum operatio ex uno, quemadmodum omnia ex uno eodemque ducunt originem, una eademque consilii administratione.

Cuius pater Sol, mater vero Luna,

eam ventus in corpore suo extollit: Terra fit dulcior.

Vos ergo, prestigiorum filii, prodigiorum opifices, discretione perfecti,

si terra fiat, eam ex igne subtili, qui omnem grossitudinem et quod hebes est antecellit, spatiosibus, et prudenter et sapientie industria, educite.

A terra ad celum conscendet, a celo ad terram dilabetur,

superiorum et inferiorum vim continens atque potentiam.

Unde omnis ex eodem illuminatur obscuritas,

cuius videlicet potentia quicquid subtile est transcendit et rem grossam, totum, ingreditur.

Que quidem operatio secundum maioris mundi compositionem habet subsistere.

Quod videlicet Hermes philosophus triplicem sapientiam vel triplicem scientiam appellat.[67]

From the Latin translation of the pseudo-Aristotelian Sirr al-asrār (Secretum secretorum)

[edit]The tablet was also translated into Latin as part of the longer version of the pseudo-Aristotelian Sirr al-asrār (Latin: Secretum Secretorum, original Arabic above). It differs significantly both from the translation by Hugo of Santalla (see above) and the Vulgate translation (see below).

Veritas ita se habet et non est dubium,

quod inferiora superioribus et superiora inferioribus respondent.

Operator miraculorum unus solus est Deus, a quo descendit omnis operacio mirabilis.

Sic omnes res generantur ab una sola substancia, una sua sola disposicione.

Quarum pater est Sol, quarum mater est Luna.

Que portavit ipsam naturam per auram in utero, terra impregnata est ab ea.

Hinc dicitur Sol causatorum pater, thesaurus miraculorum, largitor virtutum.

Ex igne facta est terra.

Separa terrenum ab igneo, quia subtile dignius est grosso, et rarum spisso.

Hoc fit sapienter et discrete. Ascendit enim de terra in celum, et ruit de celo in terram.

Et inde interficit superiorem et inferiorem virtutem.

Sic ergo dominatur inferioribus et superioribus et tu dominaberis sursum et deorsum,

tecum enim est lux luminum, et propter hoc fugient a te omnes tenebre.

Virtus superior vincit omnia.

Omne enim rarum agit in omne densum.

Et secundum disposicionem majoris mundi currit hec operacio,

et propter hoc vocatur Hermogenes triplex in philosophia.[59]

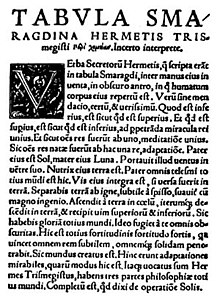

Vulgate (from the Liber Hermetis de alchimia or Liber dabessi)

[edit]

The most widely distributed Latin translation (the so-called 'Vulgate') is found in an anonymous compilation of commentaries on the Emerald Tablet that was translated from a lost Arabic original. This alchemical compilation was variously called Liber Hermetis de alchimia, Liber dabessi, or Liber rebis.[69] Its translator has been tentatively identified as Plato of Tivoli, who was active in c. 1134–1145.[70] However, this is merely a conjecture, and although it can be deduced from other indices that the text dates to the first half of the twelfth century, its translator remains unknown.[71]

The Vulgate version also differs significantly from the other two early Latin versions. A critical edition based on eight manuscripts was prepared by Robert Steele and Dorothea W. Singer in 1928:[72]

Verum sine mendacio, certum, certissimum.

Quod est superius est sicut quod inferius, et quod inferius est sicut quod est superius.

Ad preparanda miracula rei unius.

Sicut res omnes ab una fuerunt meditatione unius, et sic sunt nate res omnes ab hac re una aptatione.

Pater ejus sol, mater ejus luna.

Portavit illuc ventus in ventre suo. Nutrix ejus terra est.

Pater omnis Telesmi tocius mundi hic est.

Vis ejus integra est.

Si versa fuerit in terram separabit terram ab igne, subtile a spisso.

Suaviter cum magno ingenio ascendit a terra in celum. Iterum descendit in terram,

et recipit vim superiorem atque inferiorem.

Sicque habebis gloriam claritatis mundi. Ideo fugiet a te omnis obscuritas.

Hic est tocius fortitudinis fortitudo fortis,

quia vincet omnem rem subtilem, omnemque rem solidam penetrabit.

Sicut hic mundus creatus est.

Hinc erunt aptationes mirabiles quarum mos hic est.

Itaque vocatus sum Hermes, tres tocius mundi partes habens sapientie.

Et completum est quod diximus de opere solis ex libro Galieni Alfachimi.True it is, without falsehood, certain and most true.

That which is above is like to that which is below, and that which is below is like to that which is above,

to accomplish the miracles of one thing.

And as all things were by contemplation of one, so all things arose from this one thing by a single act of adaptation.

The father thereof is the Sun, the mother the Moon.

The wind carried it in its womb, the earth is the nurse thereof.

It is the father of all works of wonder throughout the whole world.

The power thereof is perfect.

If it be cast on to earth, it will separate the element of earth from that of fire, the subtle from the gross.

With great sagacity it doth ascend gently from earth to heaven. Again it doth descend to earth,

and uniteth in itself the force from things superior and things inferior.

Thus thou wilt possess the glory of the brightness of the whole world, and all obscurity will fly far from thee.

This thing is the strong fortitude of all strength,

for it overcometh every subtle thing and doth penetrate every solid substance.

Thus was this world created.

Hence will there be marvellous adaptations achieved, of which the manner is this.

For this reason I am called Hermes Trismegistus, because I hold three parts of the wisdom of the whole world.

That which I had to say about the operation of Sol is completed.—Steele & Singer 1928, p. 48/492 —Steele & Singer 1928, p. 42/486.

Early modern versions of the tablet text

[edit]

Latin (Nuremberg, 1541)

[edit]Despite some small differences, the 16th-century Nuremberg edition of the Latin text remains largely similar to the vulgate (see above). A translation by Isaac Newton is found among his alchemical papers that are currently housed in King's College Library, Cambridge University:

Verum sine mendacio, certum, et verissimum. |

Tis true without lying, certain and most true. |

| —Petreius, Johannes 1541. De alchemia. Nuremberg, p. 363. (available online) | —Isaac Newton. "Keynes MS. 28". The Chymistry of Isaac Newton. Ed. William R. Newman. June 2010. Retrieved 4 March 2013. |

Influence

[edit]

In its several Western recensions, the Tablet became a mainstay of medieval and Renaissance alchemy. Commentaries and/or translations were published by, among others, Trithemius, Roger Bacon, Michael Maier, Albertus Magnus, and Isaac Newton. The concise text was a popular summary of alchemical principles, wherein the secrets of the philosophers' stone were thought to have been described.[74]

The fourteenth-century alchemist Ortolanus (or Hortulanus) wrote a substantial exegesis on The Secret of Hermes, which was influential on the subsequent development of alchemy. Many manuscripts of this copy of the Emerald Tablet and the commentary of Ortolanus survive, dating at least as far back as the fifteenth century. Ortolanus, like Albertus Magnus before him saw the tablet as a cryptic recipe that described laboratory processes using deck names (or code words). This was the dominant view held by Europeans until the fifteenth century.[75]

By the early sixteenth century, the writings of Johannes Trithemius (1462–1516) marked a shift away from a laboratory interpretation of the Emerald Tablet, to a metaphysical approach. Trithemius equated Hermes' one thing with the monad of pythagorean philosophy and the anima mundi. This interpretation of the Hermetic text was adopted by alchemists such as John Dee, Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa, and Gerhard Dorn.[75]

In popular culture

[edit]In the time travel television series Dark, the mysterious priest Noah has a large image of the Emerald Tablet tattooed on his back. The image, which is from Heinrich Khunrath's Amphitheatre of Eternal Wisdom (1609), also appears on a metal door in the caves that are central to the plot. Several characters are shown looking at copies of the text.[76] A line from the Latin version, "Sic mundus creatus est" (So was the world created), plays a prominent thematic role in the series and is the title of the sixth episode of the first season.[77]

In 1974, Brazilian singer Jorge Ben Jor recorded a studio album under the name A Tábua de Esmeralda ("The Emerald Tablet"), quoting from the Tablet's text and from alchemy in general in several songs. The album has been defined as an exercise in "musical alchemy" and celebrated as Ben Jor's greatest musical achievement, blending together samba, jazz, and rock rhythms.[78]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Latin, from the Arabic: اللوح الزمرذ, romanized: al-Lawḥ al-Zumurrudh Arabic pronunciation: [al.lawħ az.zu.mur.ruð]

References

[edit]- ^ Principe 2013, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Principe 2013, p. 31.

- ^ Principe 2013, p. 32.

- ^ Newton, Isaac (June 2010). Newman, William R. (ed.). The Chymistry of Isaac Newton.

- ^ Bull 2018, pp. 1–3, 33–38

- ^ Van Bladel 2009, pp. 1–22.

- ^ Holmyard, E.J. The Emerald Table Nature, No. 2814, vol. 112, 1923, p. 525-6. - Julius Ruska Tabula Smaragdina. Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der hermetischen Literatur (1926)

- ^ Kraus, Paul 1942-1943. Jâbir ibn Hayyân: Contribution à l'histoire des idées scientifiques dans l'Islam. I. Le corpus des écrits jâbiriens. II. Jâbir et la science grecque. Cairo: Institut français d'archéologie orientale, vol. II, pp. 274-275; Weisser, Ursula 1980. Das Buch über das Geheimnis der Schöpfung von Pseudo-Apollonios von Tyana. Berlin: De Gruyter, p. 46.

- ^ (Kahn 1994, p. XII-XV)

- ^ (Kahn 1994, p. XV) citing Ursula Weisser's work Das Buch über das Geheimnis der Schöpfung (1980)

- ^ (Kahn 1994, p. XIV)

- ^ "This is the book of the wise Bélinous [Apollonius of Tyana], who possesses the art of talismans: this is what Bélinous says... In the place where I lived [Tyana], there was a stone statue raised on a wooden column; on the column, these words were written: 'I am Hermes, to whom knowledge has been given...'. While I slept uneasily and restlessly, preoccupied with my sorrow, an old man whose face resembled mine appeared before me and said, 'Rise, Bélinous, and enter this underground road; it will lead you to the knowledge of the secrets of Creation...'. I entered this underground passage. I saw an old man sitting on a golden throne, holding an emerald tablet in one hand... I learned what was written in this book of the 'Secret of the Creation of Beings'... [Emerald Tablet:] True, true, certain, indisputable, and authentic! Behold, the highest comes from the lowest, and the lowest from the highest; a work of wonders by a single thing..."

- ^ (Kahn 1994, p. XVI-XVII)

- ^ Didier Kahn, Le Fixe et le volatil, CNRS Éditions, 2016, pp. 23-23, citing Mandosio 2003, pp. 682–683.

- ^ (Kahn 1994, p. XVII) citing Julius Ruska's op. cit.

- ^ See Rachel Arié Études sur la civilisation de l'Espagne musulmane, Brill Archive, 1990 p. 159 [1]

- ^ Jack Lindsay, Les origines de l'alchimie dans l'Égypte gréco-romaine (1986) p. 202

- ^ Le livre de Cratès, Octave Houdas' French translation of the Arabic manuscript 440 from the University Library of Leiden, in Marcellin Berthelot, Histoire des sciences. La chimie au Moyen Âge, vol. III: L'alchimie arabe (1893)

- ^ H.E. Stapleton, 1933, Three Arabic Treatises on Alchemy by Muhammad bin Umail (10th Century A.D.). Memoirs of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, XII, Calcutta: "I saw on the roof of the galleries a picture of nine eagles with out-spread wings [...] On the left side were pictures of people standing ... having their hands stretched out towards a figure seated inside the Pyramid, near the pillar of the gate of the hall. The image was seated in a chair, like those used by the physicians. In his lab was a stone slab. The fingers behind the slab were bent as if holding it, an open book. On the side viz. in the Hall where the image was situated were different pictures, and inscriptions in hieroglyphic writing [birbawi]

- ^ Litwa 2018, p. 314; edition in Hudry 1997–1999.

- ^ Weisser 1980, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Thorndike 1959, pp. 24–25.

- ^ (Kahn 1994, p. XIX)

- ^ a b Mandosio 2005, p. 140

- ^ Calvet, Antoine (3 August 2022). "L'alchimie médiévale est-elle une science chrétienne ?". Les Dossiers du Grihl (in French) (Hors-série n°3). doi:10.4000/dossiersgrihl.321. ISSN 1958-9247. Archived from the original on 17 January 2024. Retrieved 17 January 2024.

- ^ Mandosio 2005, pp. 140–141

- ^ Roger Bacon, Opera hactenus inedita, fasc V: Secretum Secretorum cum glossis et notulis, edited by Robert Stelle, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1920.

- ^ (Kahn 1994, pp. 23–29).

- ^ Antoine Calvet, Alchimie - Occident médiéval in Dictionnaire critique de l'ésotérisme edited by Jean Servier, p.35

- ^ Barbara Obrist, Visualization in Medieval Alchemy International Journal for Philosophy of Chemistry, Vol. 9, No. 2 (2003), p. 131-170 online Archived 24 September 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Printed in Opuscule tres-excellent de la vraye philosophie naturelle des métaulx, traictant de l’augmentation et perfection d’iceux... par Maistre D. Zacaire,... Avec le traicté de vénérable docteur allemant Messire Bernard, conte de la Marche Trevisane, sur le mesme subject. (Benoist Rigaud, Lyon 1574). scanned copy Archived 14 October 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Telle, Joachim (1984). "Paracelselsistische Sinnbildkunst Bemerkungen zu einer pseudo-"Tabula Smaragdina" des 16. Jahrhunderts". In Seidler, Eduard; Schott, Heinz (eds.). Bausteine zur Medizingeschichte (in German). Wiesbaden: Steiner. p. 132.

- ^ a b (Faivre 1988, p. 38)

- ^ (Kahn 1994, pp. 59–74)

- ^ Conjectures sur l'origine du peuple germanique et son fondateur Hermès Trismégiste, qui pour Moïse est Chanaan, Tuitus pour Tacite, et Mercure pour les Gentils Tübingen 1684, cited by (Faivre 1988, p. 42)

- ^ B.J.T. Dobbs, Newton's Commentary on the Emerald Tablet of Hermes Trismegistus - Its Scientific and Theological Significance in Merkel, I and Debus A.G. Hermeticism and the Renaissance. Folger, Washington 1988.

- ^ Telle, Joachim (1984). "Paracelselsistische Sinnbildkunst Bemerkungen zu einer pseudo-"Tabula Smaragdina" des 16. Jahrhunderts". In Seidler, Eduard; Schott, Heinz (eds.). Bausteine zur Medizingeschichte (in German). Wiesbaden: Steiner. pp. 132–133, 135–136.

- ^ This poem is reproduced in Geheime Figuren der Rosenkreuzer, aus dem 16. und 17. Jahrhundert emblem Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, poem Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback MachineEnglish translation on levity.com Archived 22 June 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Joachim Telle L’art symbolique paracelsien : remarques concernant une pseudo-Tabula smaragdine du XVIe siècle in (Faivre 1988, pp. 184–235)

- ^ Joachim Telle L’art symbolique paracelsien : remarques concernant une pseudo-Tabula smaragdine du XVIe siècle in (Faivre 1988, p. 187)

- ^ Éliphas Lévi, Histoire de la Magie, Germer Bailliere, 1860, p. 78-79 [2] Archived 24 October 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ (Kahn 1994, p. XXI)

- ^ secret of the emerald tablet Archived 28 May 2023 at the Wayback Machine excerpt translated into English from Die Alchemie (1869)

- ^ H.P. Blavatsky Isis Unveiled Theosophical University Press, 1972. p. 507-14.

- ^ Titus Burckhardt, Alchemy Stuart and Watkins, London, 1967 p. 196 -201

- ^ See, for example, the comments by Jean-Marc Mandosio on the relationship between André Breton and alchemy in his writings in Dans le chaudron du négatif, op. cit., p. 22-25.

- ^ André Breton, Œuvres complètes – I, Gallimard, Bibliothèque de la Pléiade, 1988, p. 781. Quoted in (Kahn 1994, p. XXII)

- ^ Regarding this point, see Mark Polizzotti, André Breton, Gallimard, 1999, p. 368-369, and note 3 p. 1594-1595 in Œuvres complètes – I of Bibliothèque de la Pléiade. Henri Béhar, on the other hand, speaks of this sentence as a "quest [...] akin, proportionately, to that of the alchemist" in André Breton. Le grand indésirable, Calmann-Lévy, 1990, p. 220.

- ^ Jean-Marc Mandosio, op. cit., p. 103-104.

- ^ It was perhaps written between the sixth and eighth centuries, as conjectured by Ruska 1926, p. 166.

- ^ Weisser 1980, p. 46.

- ^ Kraus 1942–1943, vol. II, pp. 274–275 (c. 813–833); Weisser 1980, p. 54 (c. 750–800).

- ^ Kraus 1942–1943, vol. II, pp. 270–303; Weisser 1980, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Ebeling 2007, pp. 46–47, 96.

- ^ a b Zirnis 1979, pp. 64–65, 90. On the dating of the texts attributed to Jābir, see Kraus 1942–1943, vol. I, pp. xvii–lxv.

- ^ Manzalaoui 1974, p. 167; edited by Badawi 1954, pp. 166–167.

- ^ Stapleton, Lewis & Taylor 1949, p. 81.

- ^ Hudry 1997–1999. Hudry's edition of the Tablet itself is reproduced in Mandosio 2004b, pp. 690–691. An English translation may be found in Litwa 2018, p. 316.

- ^ a b Steele 1920, pp. 115–117. Steele's edition is reproduced in Mandosio 2004b, pp. 692–693.

- ^ Mandosio 2004b, p. 683. For an edition and a short description of the contents of this text, see Steele & Singer 1928 (Steele & Singer's edition of the Tablet itself is reproduced in Mandosio 2004b, pp. 691–692). See further Colinet 1995; Caiazzo 2004, pp. 700–703.

- ^ Weisser 1980, p. 46. On the dating of this text, see Kraus 1942–1943, vol. II, pp. 274–275 (c. 813–833); Weisser 1980, p. 54 (c. 750–800).

- ^ This translation was prepared by Wikipedia editors. A translation based on the superseded edition of Ruska 1926, pp. 158–159 may also be found in Rosenthal 1975, pp. 247–248.

- ^ Holmyard 1923; cf. Ruska 1926, p. 121.

- ^ On the dating of this work, see Manzalaoui 1974.

- ^ Badawi 1954, pp. 166–167.

- ^ Litwa 2018, p. 314.

- ^ Hudry 1997–1999, p. 152. Hudry's edition is reproduced in Mandosio 2004b, pp. 690–691. An English translation may be found in Litwa 2018, p. 316.

- ^ "Detailed record for Arundel 164". British Library, Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts. Archived from the original on 24 April 2023. Retrieved 24 April 2023. A transcription is given by Selwood 2023.

- ^ Mandosio 2004b, p. 683. On this text, see further Colinet 1995; Caiazzo 2004, pp. 700–703.

- ^ Steele & Singer 1928, p. 45/489.

- ^ Mandosio 2004b, p. 683.

- ^ The manuscripts are listed in Steele & Singer 1928, p. 46/490. Steele & Singer's edition of the Tablet itself is reproduced in Mandosio 2004b, pp. 691–692. A transcription of the Tablet in one manuscript, MS Arundel 164, is given by Selwood 2023 (Selwood mistakes Steele & Singer 1928's edition for a mere transcript of one manuscript; his attribution of the text's origin to the Secretum secretorum is also mistaken).

- ^ Word of Greek origin, from τελεσμός (itself from τελέω, having meanings such as "to perform, accomplish" and "to consecrate, initiate"); "th"-initial spellings represent a corruption. The obscurity of this word's meaning brought forth many interpretations. An anonymous commentary from the 12th century explains telesmus as meaning "secret", mentioning that "divination among the Arabs" was "referred to as telesmus", and that it was "superior to all others"; of this later only the meaning of "a secret" would remain in the word. The word corresponds to طلسم (ṭilasm) in the Arabic text, which does indeed mean "enigma", but also "talisman" in Arabic. It has been asserted that the original meaning was in fact in reference to talismanic magic, and that this was lost in translation from Arabic to Latin (source: Mandosio 2005). Otherwise, the word telesmus was also understood to mean "perfection", as can be seen in Isaac Newton's translation, or "treasure", or other things.

- ^ Linden 2003, p. 27.

- ^ a b Debus 2004, p. 415.

- ^ "'Dark' Theories and Burning Questions: Jonas' Fate, the Wallpapered Room, and That Massive Back Tattoo". 8 December 2017. Archived from the original on 9 December 2017. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ^ "Dark – Season 1, Episode 6: "Sic Mundus Creatus Est"". Father Son Holy Gore. 4 December 2017. Archived from the original on 17 February 2018. Retrieved 17 February 2018.

- ^ Philip Jandovský. "A Tábua de Esmeralda – Jorge Ben". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 18 July 2018. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

Sources used

[edit]- Badawi, Abd al-Rahman (1954). al-Usūl al-Yūnāniyya li-l-naẓariyyāt al-siyāsiyya fī al-islām. Cairo: Maktabat al-Nahḍa al-Miṣriyya. OCLC 12629786.

- Bull, Christian H. (2018). The Tradition of Hermes Trismegistus: The Egyptian Priestly Figure as a Teacher of Hellenized Wisdom. Religions in the Graeco-Roman World: 186. Leiden: Brill. doi:10.1163/9789004370845. ISBN 978-90-04-37084-5. S2CID 165266222.

- Caiazzo, Irene (2004). "La Tabula smaragdina nel Medioevo latino, II. Note sulla fortuna della Tabula smaragdina nel Medioevo latino". In Lucentini, P.; Parri, I.; Perrone Compagni, V. (eds.). La tradizione ermetica dal mondo tardo-antico all'umanesimo. Atti del Convegno internazionale di studi, Napoli, 20–24 novembre 2001 [Hermetism from Late Antiquity to Humanism]. Instrumenta Patristica et Mediaevalia. Vol. 40. Turnhout: Brepols. pp. 697–711. doi:10.1484/M.IPM-EB.4.00122. ISBN 978-2-503-51616-5.

- Colinet, Andrée (1995). "Le livre d'Hermès intitulé Liber dabessi ou Liber rebis". Studi medievali. 36 (2): 1011–1052.

- Debus, Allen G. (2004). Alchemy and Early Modern Chemistry: Papers from Ambix. Jeremy Mills Publishing. ISBN 9780954648411.

- Ebeling, Florian (2007). The Secret History of Hermes Trismegistus: Hermeticism from Ancient to Modern Times. Translated by Lorton, David. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-4546-0. JSTOR 10.7591/j.ctt1ffjptt.

- Faivre, Antoine (1988). Présences d'Hermès Trismégiste. Cahiers de l'Hermétisme. Éditions Albin Michel.

- Hesteau, Clovis (1639). Traittez de l'harmonie et constitution généralle du vray sel, secret des philosophes, et de l'esprit universelle du monde, suivant le troisiesme principe du Cosmopolite [Treatise on the harmony and general constitution of true salt, secret of philosophers, and of the universal spirit of the world, following the third principle of the Cosmopolitan.] (in French). The Hague: De l'Imprimerie de Theodore Maire.

- Holmyard, Eric J. (1923). "The Emerald Table". Nature. 112: 525–526. doi:10.1038/112525a0.

- Hudry, Françoise (1997–1999). "Le De secretis nature du Ps. Apollonius de Tyane, traduction latine par Hugues de Santalla du Kitæb sirr al-halîqa". Chrysopoeia. 6: 1–154.

- Mandosio, Jean-Marc (2004a). "Françoise Hudry (éd.), «Le De secretis nature du ps.-Apollonius de Tyane, traduction latine par Hugues de Santalla du Kitâb sirr al-h̲alîqa», Chrysopœia, 6, 1997-1999 [2000] [compte-rendu]". Archivum Latinitatis Medii Aevi. 62: 317–321.

- Kahn, Didier (1994). La table d'émeraude et sa tradition alchimique. Paris: Les Belles Lettres. ISBN 9782251470054.

- Kraus, Paul (1942–1943). Jâbir ibn Hayyân: Contribution à l'histoire des idées scientifiques dans l'Islam. I. Le corpus des écrits jâbiriens. II. Jâbir et la science grecque. Cairo: Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale. ISBN 9783487091150. OCLC 468740510.

- Linden, Stanton J. (2003). The Alchemy Reader: From Hermes Trismegistus to Isaac Newton. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781107050846. ISBN 0-521-79234-7.

- Litwa, M. David (2018). Hermetica II: The Excerpts of Stobaeus, Papyrus Fragments, and Ancient Testimonies in an English Translation with Notes and Introductions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781316856567. ISBN 978-1-107-18253-0. S2CID 217372464.

- Mandosio, Jean-Marc (2003). "La Tabula smaragdina e i suoi commentari medievali". In Paolo Lucentini; Ilaria Parri; Vittoria Perrone Compagni (eds.). Hermetism from late antiquity to humanism. Brepols. pp. 681–696.

- Mandosio, Jean-Marc (2004b). "La Tabula smaragdina nel Medioevo latino, I. La Tabula smaragdina e i suoi commentari medievali". In Lucentini, P.; Parri, I.; Perrone Compagni, V. (eds.). La tradizione ermetica dal mondo tardo-antico all'umanesimo. Atti del Convegno internazionale di studi, Napoli, 20–24 novembre 2001 [Hermetism from Late Antiquity to Humanism]. Instrumenta Patristica et Mediaevalia. Vol. 40. Turnhout: Brepols. pp. 681–696. doi:10.1484/M.IPM-EB.4.00121. ISBN 978-2-503-51616-5.

- Mandosio, Jean-Marc (2005). "La création verbale dans l'alchimie latine du Moyen Âge". Archivum Latinitatis Medii Aevi. 63: 137–147. doi:10.3406/alma.2005.894.

- Manzalaoui, Mahmoud (1974). "The Pseudo-Aristotelian Kitāb Sirr al-asrār: Facts and Problems". Oriens. 23/24: 147–257. doi:10.2307/1580104. JSTOR 1580104.

- Principe, Lawrence M. (2013). The Secrets of Alchemy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226103792.

- Rosenthal, Franz (1975). The Classical Heritage in Islam. London: Routledge. ISBN 9780415076937.

- Ruska, Julius (1926). Tabula Smaragdina. Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der hermetischen Literatur. Heidelberg: Winter. OCLC 6751465.

- Selwood, Dominic (2023). "The Emerald Tablet and the Origins of Chemistry". medievalists.net. Retrieved 24 April 2023.

- Stapleton, H. E.; Lewis, G. L.; Taylor, F. Sherwood (1949). "The sayings of Hermes quoted in the Māʾ al-waraqī of Ibn Umail". Ambix. 3 (3–4): 69–90. doi:10.1179/amb.1949.3.3-4.69.

- Steele, Robert (1920). Secretum secretorum cum glossis et notulis. Opera hactenus inedita Rogeri Baconi, vol. V. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 493365693.

- Steele, Robert; Singer, Dorothea Waley (1928). "The Emerald Table". Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. 21 (3): 41–57/485–501. doi:10.1177/003591572802100361. PMC 2101974. PMID 19986273.

- Thorndike, Lynn (1959). "John of Seville". Speculum. 34 (1): 20–38. doi:10.2307/2847976. ISSN 0038-7134. JSTOR 2847976.

- Van Bladel, Kevin (2009). The Arabic Hermes: From Pagan Sage to Prophet of Science. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195376135.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-537613-5.

- Weisser, Ursula (1979). Buch über das Geheimnis der Schöpfung und die Darstellung der Natur (Buch der Ursachen) von Pseudo-Apollonios von Tyana. Sources and Studies in the History of Arabic-Islamic Science. Aleppo: Institute for the History of Arabic Science. OCLC 13597803.

- Weisser, Ursula (1980). Das "Buch über das Geheimnis der Schöpfung" von Pseudo-Apollonios von Tyana. Berlin: De Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9783110866933. ISBN 978-3-11-086693-3.

- Zirnis, Peter (1979). The Kitāb Usṭuqus al-uss of Jābir ibn Ḥayyān (Unpublished PhD diss.). New York University.

Further reading

[edit]- Davis, Tenney L. (1926). "The Emerald Table of Hermes Trismegistus. Three Latin Versions Which Were Current among Later Alchemists". Journal of Chemical Education. 3 (8): 863–875. doi:10.1021/ed003p863.

- Dobbs, Betty J. T. (1988). "Newton's Commentary on The Emerald Tablet of Hermes Trismegistus: Its Scientific and Theological Significance". In Merkel, Ingrid; Debus, Allen G. (eds.). Hermeticism and the Renaissance: Intellectual History and the Occult in Early Modern Europe. Washington, D.C.: The Folger Shakespeare Library. pp. 182–191. ISBN 9780918016850.

- Forshaw, Peter (2007). "Alchemical Exegesis: Fractious Distillations of the Essence of Hermes". In Principe, Lawrence M. (ed.). Chymists and Chymistry: Studies in the History of Alchemy and Early Modern Chemistry. Sagamore Beach, MA: Science History Publications. pp. 25–38. ISBN 9780881353969.

- Holmyard, E.J., Alchemy, Pelican, Harmondsworth, 1957. pp 95–98.

- Needham, J., Science and Civilisation in China, vol. 5, part 4: Spagyrical discovery and invention: Apparatus, Theories and gifts. CUP, 1980.

- Plessner, Martin (1927). "Neue Materialien zur Geschichte der Tabula Smaragdina". Der Islam. 16 (1): 77–113.

- Quispel, Gilles (2000). "Gnosis and Alchemy: The Tabula Smaragdina". In Van den Broek, Roelof; Van Heertum, Cis (eds.). From Poimandres to Jacob Böhme: Gnosis, Hermetism and the Christian Tradition. Leiden: Brill. pp. 303–333. doi:10.1163/9789004501973_014. ISBN 978-90-71-60810-0.

- Ruska, Julius (1925). "Der Urtext der Tabula Smaragdina". Orientalistische Literaturzeitung. 28: 349–351.

- Ruska, Julius. Quelques problemes de literature alchimiste. n.p., 1931.

- Ruska, Julius. Die Alchimie ar-Razi's. n.p., 1935.

- M. Robinson. The History and Myths surrounding Johannes Hispalensis, in Bulletin of Hispanic Studies vol. 80, no. 4, October 2003, pp. 443–470, abstract.