Every Man for Himself (1980 film)

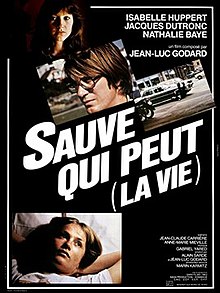

| Sauve qui peut (la vie) Every Man for Himself Slow Motion | |

|---|---|

French poster | |

| Directed by | Jean-Luc Godard |

| Written by | Jean-Claude Carrière Jean-Luc Godard Anne-Marie Miéville |

| Produced by | Jean-Luc Godard Alain Sarde |

| Starring | Jacques Dutronc Isabelle Huppert Nathalie Baye |

| Cinematography | Renato Berta William Lubtchansky Jean-Bernard Menoud |

| Edited by | Jean-Luc Godard Anne-Marie Miéville |

| Music by | Gabriel Yared |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | MK2 Diffusion |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 87 minutes |

| Countries | France Austria West Germany Switzerland |

| Language | French |

Every Man for Himself (French: Sauve qui peut (la vie)) is a 1980 drama film directed, co-written and co-produced by Jean-Luc Godard that is set in and was filmed in Switzerland. It stars Jacques Dutronc, Isabelle Huppert, and Nathalie Baye, with a score by Gabriel Yared. Nathalie Baye won the César Award for Best Supporting Actress. It also was submitted as the Swiss entry for the Best Foreign Language Film at the 53rd Academy Awards, but was not accepted as a nominee.

Constructed as a musical piece, it has a prologue followed by three movements, each of which focuses on one of the three key characters and their interactions with the others, and ends with a coda. Throughout the film an unnamed piece of music recurs, which is the aria Suicidio! (Suicide!) from the opera La Gioconda by Ponchielli.[2] Serving as leitmotiv for the whole story, it underscores the innate death-wish haunting the central character.[3]

Plot

[edit]The prologue introduces Paul Godard, a filmmaker, and his estranged girlfriend, Denise, in which a stressed Paul leaves the deluxe hotel to which he has moved and rebuffs the sexual advances of a male hotel attendant.

The first section, "The Imaginary," follows Denise as she takes her first steps to an independent life without Paul. She lands a manual job on a local paper run by an old friend, perhaps an old lover, in a country town and gets a room on a farm in return for helping with the cattle. She is also writing up some new project, which may become a novel. At the same time, she has to complete her job at the television station where she and Paul work, as well as find a new tenant for her flat in the city where she and Paul have been living together. Realising she is late to collect the author and filmmaker Marguerite Duras for an interview, she telephones Paul to ask if he can do it for her. Despite being in no mood to agree with her, he accepts.

The second section, "Fear," focuses on Paul. He is afraid of life without Denise, perhaps of life itself. After picking up his surly daughter Cécile from soccer practice, at which seemingly apropos of nothing he asks the coach if he has ever felt like touching or having sex with his own daughter, he fulfils his favour to Denise by collecting Marguerite Duras from a local college, where she was due to give a talk. When she refuses to do so (her voice is heard but she is not shown), Paul reads out some of her notes, in which she says that she only makes films because she lacks the courage to do nothing. Paul says this is true for himself as well. The celebrity then gets Paul to take her back to the airport, after which he has to face a furious Denise who has lost her interviewee. That evening, as it is Cécile's birthday, he takes her and her mother to a restaurant but all his scornful ex-wife wants is money and all the girl wants is presents. Leaving in fury, after again expressing his alienation with inappropriate sexual innuendo, he meets Denise in a bar, where the two quarrel and part. Standing alone in a late-night cinema queue, he is picked up by the prostitute Isabelle.

Part Three, "Commerce," is Isabelle's section, in which she devotes herself to increasing her earnings in order to achieve independence. After her night with Paul, in which she mechanically goes through the motions while mentally planning her next day, she is waylaid by a pimp who gives her a spanking to remind her that there is no independence in a commercial world and he must have 50% of her earnings. On returning to the apartment she shares with some other women, who all seem to detest her, her younger sister arrives unexpectedly and asks Isabelle for money because her lover and all his associates have just been jailed for robbing a bank. When Isabelle refuses, the sister asks if she will get her started in the local prostitution business. Isabelle agrees to coach her for a month, in exchange for 50% of the take. While continuing to service a variety of clients with different needs, sometimes inventive (one businessman choreographs a foursome while sitting at his desk), and all the while with her mind elsewhere, she is also searching for an apartment of her own. An old school friend she meets in a hotel corridor, probably a dealer and maybe a prostitute as well, offers her a lucrative opportunity to be a courier, but the boss of the operation finds Isabelle too dangerously naive. Going to inspect an apartment, it turns out to be that of Denise, and Paul is also there trying to rekindle the relationship. Isabelle and Denise form an immediate bond.

In the coda, entitled "Music," Isabelle seems to prosper in her new apartment and Denise has moved on in life. After having spent several days adrift, Paul runs into his ex-wife and daughter and asks plaintively to spend more time with them. Walking backwards away from the two, Paul accidentally steps in front of a car and is hit. Isabelle's sister, now apparently a prostitute, flees the scene with the driver of the car, her client. Paul's ex-wife also urges Cécile to come away, saying "it's nothing to do with us." As the two walk off, they pass a small orchestra set up in a garage yard that is playing the theme music which has echoed through the film.

Cast

[edit]- Jacques Dutronc as Paul Godard

- Isabelle Huppert as Isabelle Rivière

- Nathalie Baye as Denise Rimbaud

- Cécile Tanner as Cecile, Paul's daughter

Background

[edit]After twelve years of low budget, militant left-wing, and otherwise experimental film and video projects outside of commercial distribution, Every Man for Himself was Godard's return to "mainstream" filmmaking, with a sizable budget and French film stars. Godard promoted what he referred to as his "second first film" heavily in the United States, notably appearing on two episodes of The Dick Cavett Show. Nevertheless, in addition to Godard's typical refusal to keep viewers oriented through expository dialogue and continuity editing, the film is experimental in its use of the technique that Godard called "decomposition," which he first employed for the 1979 French television series France/tour/détour/deux/enfants. In the technique, there is a periodic slowing down of the action to a frame by frame advancement. Consequently, the film was given the name Slow Motion when it was released in the UK. The French title Sauve Qui Peut literally means "save who can," and is a common phrase shouted among a crowd of people when there is danger—hence the American title of the film, Every Man for Himself. Godard has stated that a better title in American English would be "Save Your Ass."

In his initial proposal for the film, a 20 minute video known as Scénario de Sauve Qui Peut (la vie) (included as a supplement on the Criterion Collection DVD), Godard suggested a guest appearance by Werner Herzog that is not in the finished film, including a still photo that is apparently of Herzog doing a backflip. Perhaps this is a joke, Herzog having made Every Man for Himself and God Against All six years earlier.

Poet and author Charles Bukowski is credited with the English subtitles for the American release though he doesn't speak French. He adapted existing subtitles translated to English from the original French.

Reception

[edit]Release and box office

[edit]The film premiered at the 1980 Cannes Film Festival, and went on to garner 620,147 admissions in France.[4]

Critical response

[edit]Every Man for Himself has an approval rating of 90% on review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, based on 10 reviews, and an average rating of 8.9/10.[5]

Film critic Vincent Canby, writing in The New York Times, described the film effusively as "stunning," "beautiful," and "brilliant".[6]

In the 2012 Sight & Sound polls of the greatest films ever made, Every Man for Himself made the top-10 lists of two critics and two directors.[7]

Awards and honors

[edit]- 1980 Cannes Film Festival (France)

- Nominated: Palme d'Or (Jean-Luc Godard)[8]

- César Awards (France)

- Won: Best Actress – Supporting Role (Nathalie Baye)

- Nominated: Best Director (Jean-Luc Godard)

- Nominated: Best Film

It was submitted as the Swiss entry for the Best Foreign Language Film at the 53rd Academy Awards, but was not accepted as a nominee.[9]

See also

[edit]- Isabelle Huppert on screen and stage

- List of submissions to the 53rd Academy Awards for Best Foreign Language Film

- List of Swiss submissions for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film

References

[edit]- ^ "American Zoetrope Filmography". zoetrope.com. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- ^ "SWISS FILMS: Sauve Qui Peut (la vie)". www.swissfilms.ch.

- ^ "Beim Leben erwischt". Der Spiegel. 23 November 1981 – via Spiegel Online.

- ^ "Sauve qui peut (la vie) (1980)". JPBox-Office. 1980-10-15. Retrieved 2019-04-11.

- ^ "Every Man for Himself". Rotten Tomatoes.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (8 October 1980). "Movie Review: Every Man for Himself (1979), NYT Critics' Pick". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 September 2011.

- ^ "Votes for Sauve qui peut (la vie) (1979)". www.bfi.org.uk. Archived from the original on January 14, 2019. Retrieved 2019-01-14.

- ^ "Festival de Cannes: Sauve qui peut (la vie)". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 2009-05-28.

- ^ Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

External links

[edit]- 1980 films

- 1980s avant-garde and experimental films

- French avant-garde and experimental films

- Austrian drama films

- Swiss drama films

- West German films

- 1980s French-language films

- Films directed by Jean-Luc Godard

- Films scored by Gabriel Yared

- Films with screenplays by Jean-Claude Carrière

- American Zoetrope films

- French-language Swiss films

- German drama films

- French drama films

- 1980s French films

- 1980s German films

- Films featuring a Best Supporting Actress César Award–winning performance