Alistair McAlpine, Baron McAlpine of West Green

The Lord McAlpine of West Green | |

|---|---|

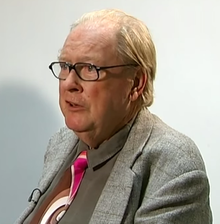

McAlpine in 2012 | |

| Member of the House of Lords | |

| In office 2 February 1984 – 26 May 2010 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Robert Alistair McAlpine 14 May 1942 Mayfair, London, England |

| Died | 17 January 2014 (aged 71) Diso, Lecce, Italy |

| Children | 3 |

Robert Alistair McAlpine, Baron McAlpine of West Green[1] (14 May 1942 – 17 January 2014) was a British businessman, politician and author who was an advisor to Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher.[2]

McAlpine was descended from the McAlpine baronets who made their fortune in the construction industry. McAlpine held a variety of jobs before becoming prominent in British politics in the 1980s as the treasurer and a major fundraiser of the Conservative Party. A close ally of Thatcher, McAlpine did not support her successor as Prime Minister John Major, and later joined James Goldsmith's Referendum Party. McAlpine later rejoined the Conservatives but resigned his seat in the House of Lords.

Outside politics McAlpine was prominent in a variety of business developments in Australia as well as being an art collector and memoirist.

Early life and business career

[edit]McAlpine was born at The Dorchester in Mayfair, London.[3] His great-grandfather was "Concrete Bob", Robert McAlpine,[2] the first of the McAlpine baronets and the founder of the McAlpine construction firm. He was the second son of Ella Mary Gardner (Garnett) and Edwin McAlpine, the fifth Baronet, and the brother of William McAlpine, the sixth Baronet. He described his childhood as "idyllic" but not luxurious.[4] He went to boarding school at the age of six.[4] He had dyslexia and left Stowe School at 16 with three O-levels.[4][5] He then worked on a McAlpine building site on the South Bank, keeping time and dealing with wage packets.[4][6]

At the age of 21, McAlpine became a director of the company, at the time named Sir Robert McAlpine & Sons.[6] He made money in property development in Australia and worked in the building business until he entered politics.[2]

McAlpine founded his own publishing house in London in the 1960s, and was an art dealer, art collector, zookeeper (in Broome, Western Australia), horticulturist, beekeeper, agriculturist, gardener and passionate traveller.[1]

Politics

[edit]Though the inner circle of the Labour Prime Minister Harold Wilson had once considered appointing McAlpine as a fundraiser, McAlpine was entranced by the new Conservative Party leader Margaret Thatcher at a 1975 dinner party, and she soon appointed him Conservative treasurer, a position he would retain until 1990.[6] They continued to have a close working relationship throughout her time as prime minister[2] and he led the fundraising efforts for the Conservative's general election campaigns.[2] He would later describe his relationship with Thatcher in his book The Servant.[2] Using Machiavelli's The Prince for his analogy, the "Servant" (himself) is an important part of the success of the "Prince" (Thatcher).[2][6] McAlpine's obituary in The Daily Telegraph described him as "... probably the most successful fundraiser the party ever had; yet by nature a dilettante, he did not become a significant political figure" and "... never really "into" politics. At heart he was an 18th-century amateur"[3]

McAlpine's personal political views were varied and included Euroscepticism, support for electric cars and the decriminalisation of all drugs.[3]

McAlpine was nominated to the Arts Council of Great Britain in 1980, despite protests at a perceived lack of experience in the field and his opposition to public subsidisation of the arts.[7] He served on the Council from 1981 to 1982.[8] Other public bodies on which McAlpine served included the Theatre Investment Fund, of which he was chairman.[3] He was also a trustee of the Royal Opera House and a director of the Institute of Contemporary Arts.[3]

McAlpine was created a life peer in the 1984 New Year Honours,[9] taking the title Baron McAlpine of West Green, of West Green in the County of Hampshire.[8][10]

As party treasurer, McAlpine raised large sums to support the Conservative Party in elections.[2] Often this was done over lunches with business leaders, by pointing out the problems with Labour candidates.[6] Money would never be discussed directly at the lunches, McAlpine would later say that "I used to lurk...I lurked all over London where rich people went."[3] The Conservative party had raised £1.5 million the year before McAlpine became treasurer, the figures had increased to £4 million by the 1979 general election, and more than £9 million by the time of Thatcher's departure in 1990.[3] McAlpine also channelled funds through offshore accounts, and received funds from US and Hong Kong nationals.[6] One of the funders of the era was Asil Nadir of Northern Cyprus, who was in 2012 convicted of stealing money from the Polly Peck company.[6] McAlpine said the Conservative party had a "moral duty" to return Nadir's donations, totaling £400,000, to the creditors of Polly Peck.[11] Other foreign businessmen courted by McAlpine included Li Ka-shing and Mohamed Al-Fayed.[3] McAlpine also claimed that he worked to help Major raise a large sum from Greek businessman Yiannis Latsis, though Major denied it.[12][13]

McAlpine was allegedly on a target list of the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA).[14] He was on Thatcher's team when the IRA bombed the Grand Hotel in Brighton in 1984, but was not injured.[2] In 1990 the IRA bombed[15] West Green House, a mansion in Hartley Wintney,[14] where he had lived just weeks before, and where in the past Thatcher had been a guest.[14] In the mid-1980s, for reasons of safety and tax, McAlpine decided to move to Monaco and Venice. Before his departure he had sold many of his possessions at Sotheby's.[3]

McAlpine was deputy chairman of the party from 1979 to 1983.[6] After Thatcher left in 1990, he remained fiercely supportive of her, and dismissive of her successor John Major, particularly his policies on the European Union. McAlpine joined James Goldsmith's Referendum Party six months before the 1997 general election, chairing its October 1996 party conference.[3] He was expelled from the Conservatives in the House of Lords soon thereafter.[16][17] In 1997 he became the Referendum Party's leader following Goldsmith's death,[18][19] although the party would soon become defunct. He was very critical of the Conservative Party under William Hague[2] and sat as an Independent Conservative for some time in the House of Lords before rejoining[when?] the Conservatives.

In 1997 McAlpine was briefly involved in the movement by some British conservatives to help Chechnya, especially by trying to support its oil industry.[20] Alongside former Chechen mafia boss and Chechen First Deputy Premier Khozh-Ahmed Noukhaev he created the private holding company Caucasian Common Market.

In order to maintain his non-domiciled status and so be able to avoid paying UK residents' taxes, McAlpine stepped down from his seat in the House of Lords in 2010 because of a constitutional amendment to the British tax code.[21]

McAlpine liked the Conservative Party chairman Cecil Parkinson, and disliked Parkinson's successor, John Gummer, whom he thought dull.[3] Owing to his influence over Thatcher, McAlpine was said to have ensured Gummer's replacement as party chairman by Norman Tebbit.[3]

Australia

[edit]

McAlpine first went to Western Australia around 1960, after hearing that the government was to privatise road-building.[4] In the mid-1960s he went to Perth to work, developing office blocks[4] and the first five-star hotel in the city.[4]

In the 1980s McAlpine attempted to invigorate the tourism business in Broome. McAlpine had first been impressed with Broome in the late 1970s.[22] He felt the area had great tourism potential. He invested $500 million on various developments, such as restoring crumbling buildings,[23] fixing up a cinema, and creating the Cable Beach Resort club[22] and the Pearl Coast Zoological Gardens.[24] He bought a stake in a pearl farm, and helped promote the South Sea Pearl.[22] He promoted local culture including Aboriginal artwork. He spent several months a year there, for a time.[23]

McAlpine gave to charities as well as startup businesses.[23] The changes were not without controversy,[22] explored for example in the 1990 documentary film Lord of the Bush by Tom Zubrycki.[25] Economic conditions worsened in the early 1990s, and tourism was affected by the 1989 Australian pilots' dispute.[23] McAlpine had to sell his stakes and leave in the mid-1990s.[23] The zoo closed, but many of his efforts lasted, such as the Cable Beach club. When he revisited Broome in 2012 he was described positively in several media stories and the town leaders honoured him as Freeman of the Municipality.[4][22][24]

Art and collecting

[edit]McAlpine had been a passionate collector of a wide range of objets d'art and ephemera since his youth. He had a "cupboard of curiosities" as a child, including a snake in a bottle, and a piece of a Zeppelin air ship.[3] Later objects collected by McAlpine included beads, books, furniture, police truncheons, dolls, textiles, ties, sculpture, rare breeds of chicken, Renaissance tapestries, a five-legged lamb in formaldehyde, and a dinosaur penis.[3][26][27] He was an early collector of the American painter Mark Rothko.[2] He was very interested in Abstract expressionism and artists such as Morris Louis and Jackson Pollock.[26] He also collected the work of Australian painter Sidney Nolan.[26] McAlpine made collections of folk art from various continents.[26] In the 1980s he commissioned 100 stone sculptures of human heads from Big John Dodo, at a price of A$1,000 per head.[28] He was also interested in modern sculpturists such as William Turnbull, Naum Gabo, Michael Bolus and David Annesley.[26] He owned a gallery on Cork Street as well.[6] He once owned a warehouse to store his collections, but also he periodically sold or donated portions of them to museums.[29]

In 1970 McAlpine donated 60 sculptures to the Tate, including works by Turnbull, Annesley, and Bolus, as well as Phillip King, Tim Scott, William Tucker, and Isaac Witkin.[30] McAlpine also donated hundreds of erotic pictures to the Art Gallery of New South Wales, including works by Bob Carlos Clarke, Karl Lagerfeld, David Bailey, Terence Donovan, and others. Bloomsbury Book Auctions sold many of these items in 2003. The auction was entitled "A (Very) Private Collection: Fashion and Eroticism Photographs 1970–1990".[31]

In the 1970s McAlpine and the classical architect Quinlan Terry constructed various follies in the grounds of West Green House.[32] One of these, a 50 foot high column topped by an elaborately carved design, bears a Latin inscription declaring that "this monument was built with a great deal of money which otherwise someday would have been given into the hands of the public revenue".[33] McAlpine also constructed a classical triumphal arch topped with an obelisk that bears a plaque dedicating the arch to the "first lady Prime Minister of Great Britain".[33] Other features in the folly garden include a trompe-l'œil nymphaeum, a smoke house, an "eye catcher", Chinese cow sheds and an island gazebo.[33]

Personal life

[edit]McAlpine lived in several parts of the world including England,[6] Western Australia,[6] Paris,[citation needed] Venice[6] and Southern Italy.[34]

In 1987 he had heart bypass surgery, which led him to relax his lifestyle and stop smoking.[6] In 1999 he had further heart bypass surgery, which led to complications resulting in his having a tracheotomy and, as a result of that, difficulty in speaking.[2][35] He was in a coma for a month on a life-support machine following his second heart operation,[3] after which he experienced a deathbed conversion to Catholicism. He emerged declaring that he felt "more casual about life".[3]

Marriages

[edit]McAlpine was married three times.[36] He married for the first time in 1964, to Sarah Baron.[3] They had two daughters together and divorced shortly after McAlpine became the Conservative Party treasurer.[3] His two daughters did not speak to him for years following the divorce.[3]

McAlpine married his second wife, Romilly Hobbs, in 1980.[3] She had been his political secretary and was a "glamorous and popular hostess" during Thatcher's premiership. McAlpine and Hobbs had a daughter, cook book writer Skye McAlpine,[37] and divorced shortly after McAlpine's second heart operation, owing to his adultery.[3] McAlpine said of his relationships that "I keep changing my life, houses and relationships. I reinvent myself every few years. My first marriage lasted 15 years and this one [to Romilly] 20. It's hardly into bed and out the other side. There was a great deal of love. But there comes a point when life is just a habit, and I'm rather against habits. I just didn't want to carry on."[3]

In early 2002 McAlpine married his third wife, Athena Malpas.[4] She was born in Dublin of a Greek shipping family. The couple met when she was working for the youth wing of the Referendum Party, and married in Paris, with his reconciled daughters present. She was 32 and he 59. They moved to Southern Italy, renovated an old convent, and opened a bed and breakfast.[34][38] Convento di Santa Maria di Costantinopoli is near the village of Diso, in the vicinity of the coastal city of Lecce.

False allegations of child abuse

[edit]In November 2012, McAlpine was falsely implicated in the North Wales child abuse scandal, after the BBC Newsnight programme accused an unnamed "senior Conservative" of abuse.[39] McAlpine was widely rumoured on Twitter and other social media platforms to be the person in question.[39] After The Guardian reported that the accusations were the result of mistaken identity,[40] McAlpine issued a strong denial that he was in any way involved.[41] The accuser, a former care home resident, unreservedly apologised after seeing a photograph of McAlpine and realising that he had been mistaken, leading to a report in The Daily Telegraph that the BBC was "in chaos".[42] The BBC also then apologised.[42]

The decision to broadcast the Newsnight report without contacting McAlpine first led to further criticism of the BBC, and to the resignation of its Director-General, George Entwistle.[43] The BBC subsequently paid McAlpine £185,000 in damages plus costs, which he donated to charity.[44] He also won £125,000 in damages plus costs from ITV following a November 2012 edition of This Morning which linked Conservative politicians to allegations of child sex abuse, again donating the damages to charity.[45][46]

McAlpine expressed his intention to pursue twenty "high profile" Twitter users who had reported or alluded to the rumours.[47] He decided to drop the defamation claims against those with fewer than 500 followers in return for a £25 donation to the Children in Need charity.[48] One high-profile case was settled out of court: in March 2013, McAlpine's representatives reached an agreement with writer George Monbiot, who had tweeted on the case and had at that time more than 55,000 followers on Twitter, for the latter to carry out work on behalf of three charities of his choice whose value amounts to £25,000 as compensation. Monbiot described this settlement as "unprecedented" and "eminently decent", reflecting well on McAlpine.[49]

Another case went to court: McAlpine v Bercow. The defendant was Sally Bercow, the wife of John Bercow, Speaker of the House of Commons, a high-profile, politically neutral role. On 24 May 2013, the High Court of Justice ruled that her tweet, "Why is Lord McAlpine trending? *innocent face*", was libellous. The two parties agreed on a settlement, and McAlpine donated the damages awarded to the charity Children in Need.[50][51]

Death

[edit]McAlpine died on 17 January 2014 at his home in Italy, aged 71.[5]

Arms

[edit]  |

|

Writing

[edit]McAlpine wrote (sometimes in collaboration) a number of books and contributed to periodicals, including The World of Interiors.[2][53] A partial bibliography follows.

- The Servant. London: Faber & Faber, 1992. ISBN 9780571173402.[2][54] This work discusses his relationship with Thatcher.[2][6] He later re-released it as part of a compilation called The Ruthless Leader, which also included The Art of War by Sun Tzu and The Prince by Niccolò Machiavelli, along with an introduction.[55]

- Letters to a Young Politician – From his uncle. London: Faber & Faber, 1995. ISBN 9780571170579.[56]

- Once a Jolly Bagman: Memoirs. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1997. ISBN 9780297817376.[54]

Contains numerous critical comments about former associates such as John Major, Edward Heath, and Michael Heseltine.[13]

- The New Machiavelli: The art of politics in business. New York; Chichester: John Wiley, 1998. ISBN 9780471350958.[54][57]

- Collecting and Display, with Cathy Giangrande. London: Conran Octopus, 1998. ISBN 9781850299561.[54]

- The Collector's Companion: A source book of public collections in Europe and the USA, with Cathy Giangrande. London: Everyman, 2001. ISBN 9781841590806.[54]

- Bagman to Swagman. London: Allen & Unwin, 1999. ISBN 9781865083896.[53][54]

- Adventures of a Collector. London: Allen & Unwin, 2002. ISBN 9781865087863.[53][54]

- Triumph from Failure: Lessons from Life for Business Success, with Kate Dixey. New York: Texere, 2003. ISBN 9781587991813.[54]

References

[edit]- Headley, Gwyn and Meulenkamp, Wim. (1986) Follies: A National Trust Guide Jonathan Cape ISBN 978-0-22402-105-0

- ^ a b "The Rt Hon the Lord McAlpine of West Green Authorised Biography". Debrett's People of Today. London: Debretts. Archived from the original on 6 November 2012. Retrieved 9 November 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Simon Hattenstone (11 March 2001). "I'm in the market, Tony". The Guardian. London.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v "Lord McAlpine of West Green – obituary". The Daily Telegraph. London. 18 January 2014. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Who are you? Lord Alistair McAlpine". 22 March 2012. ABC Perth (Australia) audio interview with Geoff Hutchison, in Broome studios. Text summary by Tamara Binama. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- ^ a b "Tory grandee Lord McAlpine dies in home in Italy". BBC News. 18 January 2014. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Profile: Lord Midas, his zenith and nadir: Lord McAlpine, party treasurer for Mrs Thatcher". The Independent. London. 19 June 1993. Archived from the original on 6 November 2012.

- ^ Stefan Collini (28 October 2000). "Culture Inc". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

- ^ a b "The Rt Hon the Lord McAlpine of West Green". Debretts. Archived from the original on 6 November 2012.

- ^ "Queen Elizabeth honors politicians, actor, writer". The Ledger. Lakeland, Florida. Associated Press. 1 January 1984. p. 13A. Retrieved 5 November 2012.

- ^ "No. 49641". The London Gazette. 7 February 1984. p. 1747.

- ^ Andrew Sparrow and agencies (24 August 2012). "Tory party 'has moral duty' to return £440,000 in donations from Polly Peck". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- ^ Kevin Maguire; Will Woodward (4 March 1997). "Get the Greek's cash". The Mirror. London. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ^ a b Sarah Whitebloom (15 March 1997). "McAlpine: The victims speak". The Spectator. London. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ^ a b c "IRA Suspected In Bombing Of Home Used By Conservative Party Figure". Associated Press Archive. 13 June 1990. Retrieved 3 November 2012. Describes location of mansion, Thatcher visit, residency.

- ^ "IRA Claims Blame in Wave of Blasts". Los Angeles Times. 16 June 1990.

- ^ Colin Brown (8 October 1996). "McAlpine may lose Tory whip". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014.

- ^ "Former Thatcher ally is expelled by Tories". The Independent. London. 25 October 1996. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014.

- ^ "Top 50 most influential people of Margaret Thatcher's era [K-M]". The Daily Telegraph. London. 9 April 2008. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- ^ John Rentoul (16 March 1995). "Lord McAlpine: Tories should lose the election". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 21 June 2013.

- ^ Matthew Evangelista (2002). The Chechen Wars: Will Russia Go the Way of the Soviet Union?. Washington DC: Brookings Institution. p. 54. ISBN 9780815724988. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- ^ The Guardian. For Lord retirement lists see also "Tory donor Lord Ashcroft gives up non-dom tax status". BBC News. 7 July 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Stephen Fay (30 March 2012). "Lord Knows". The Global Mail. Sydney. Archived from the original on 8 November 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Flip Prior (8 January 2011). "McAlpine re-enters Broome debate". The West Australian (Perth). Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- ^ a b Flip Prior (15 March 2012). "Lord returns to tourism 'ark'". The West Australian (Perth). Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- ^ "Lord of the bush", Bibliographic record from the National Library of Australia, for 1990 film directed by Tom Zubrycki. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Susan Moore (1 July 2011). "The Inveterate Collector". Apollo Magazine. London. Archived from the original on 17 January 2013.

- ^ "From Rothko to rag dolls: A voracious collector sells his textiles". The Economist. London. 26 May 2007. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- ^ Jorgensen, Darren (2019). "Big John Dodo and Karajarri histories" (PDF). Aboriginal History. 43. ANU Press: 77–92. doi:10.22459/AH.43.2019.04.

- ^ Joanna Pitman (12 May 2007). "Material World". The Spectator. London. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- ^ "Tate Gallery".

- ^ Kate McClymont (17 May 2003). "Expressing the flesh in chic circles". The Sydney Morning Herald.

- ^ Headley and Meulenkamp 1986, p. 78.

- ^ a b c Headley and Meulenkamp 1986, p. 79.

- ^ a b Sandra Ballentine (15 May 2005). "The Originals: Alistair and Athena McAlpine – Innkeepers". The New York Times.

- ^ "Obituary: Lord McAlpine 1942-2014". BBC News. 9 November 2012. Archived from the original on 5 July 2023.

- ^ The Independent

- ^ "Skye McAlpine, A Table for Friends". The Australian. 1 September 2020. Retrieved 18 December 2022.

- ^ Rita Konig (25 August 2011). "There's No Place Like (Someone Else's) Home". The Wall Street Journal. New York.

- ^ a b David Leigh (10 November 2012). "The Newsnight fiasco that toppled the BBC director general". The Observer. London. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- ^ "'Mistaken identity' led to top Tory abuse claim". The Guardian. London. 8 November 2012. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- ^ "Lord McAlpine responds: statement in full". The Daily Telegraph. London. 9 November 2012. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- ^ a b Sam Marsden; Gordon Rayner (9 November 2012). "BBC in chaos as abuse victim says Lord McAlpine was not my attacker". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- ^ Ben Fenton; Andrew Edgecliffe-Johnson; Hannah Kuchler (11 November 2012). "BBC director-general Entwistle resigns". Financial Times. London. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- ^ "BBC reaches settlement with Lord McAlpine". BBC News. 15 November 2012.

- ^ Mark Sweney (22 November 2012). "ITV to pay Lord McAlpine £125,000 in damages". The Guardian. London.

- ^ Josh Halliday (18 December 2012). "BBC and ITV apologise to Lord McAlpine for sex abuse allegations". The Guardian. London.

- ^ Ben Dowell (23 November 2012). "McAlpine libel: 20 tweeters including Sally Bercow pursued for damages". The Guardian. London.

- ^ Ellen Branagh (21 February 2013). "Lord McAlpine drops defamation claims against Twitter users with fewer than 500 followers". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 24 February 2013.

- ^ George Monbiot – My Agreement with Lord McAlpine 12 March 2013. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- ^ "High Court: Sally Bercow's Lord McAlpine tweet was libel". BBC News. 24 May 2013. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- ^ Dowell, Ben (23 November 2012). "McAlpine libel: 20 tweeters including Sally Bercow pursued for damages". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ^ "Life Peerages – M".

- ^ a b c Adventures of a Collector. London: Allen and Unwin. 2002. ISBN 9781865087863. Archived from the original on 27 April 2012. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Worldcat author search, from the Online Computer Library Center, 3 November 2012.

- ^ Howard Hyman (20 September 2000). "Book of the Week: Want to be a ruthless boss? Read Machiavelli". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 27 March 2009. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- ^ Andrew Marr (18 March 1995). "Book review: Rich coves in tweed suits – Letters to a Young Politician". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ^ "The New Machiavelli: The Art of Politics in Business". Publishers Weekly. New York. 11 February 1998.

External links

[edit]- 1942 births

- 2014 deaths

- 20th-century English businesspeople

- 21st-century English businesspeople

- 20th-century English memoirists

- 21st-century English memoirists

- 20th-century Roman Catholics

- 21st-century Roman Catholics

- People from Mayfair

- British people of Scottish descent

- People educated at Stowe School

- British art collectors

- Art dealers from London

- British zoologists

- British beekeepers

- British non-fiction writers

- British publishers (people)

- British expatriates in Australia

- British expatriates in Italy

- British expatriates in Monaco

- People with non-domiciled status in the United Kingdom

- People educated at Sandroyd School

- British male writers

- Converts to Roman Catholicism

- British drug policy reform activists

- Provisional Irish Republican Army actions in England

- Child abuse in the United Kingdom

- Conservative Party (UK) officials

- Conservative Party (UK) life peers

- Younger sons of baronets

- Sons of life peers

- McAlpine family

- British male non-fiction writers

- Children of peers and peeresses created life peers

- Life peers created by Elizabeth II

- Writers from London

- Peers retired from the House of Lords