Pupil

| Pupil | |

|---|---|

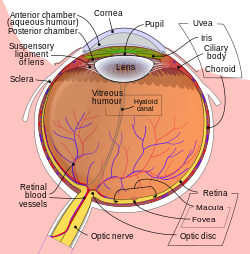

The pupil is the central opening of the iris on the inside of the eye, which normally appears black. The grey/blue or brown area surrounding the pupil is the iris. The white outer area of the eye is the sclera. The central outermost transparent colorless part of the eye (through which we can see the iris and pupil) is the cornea. | |

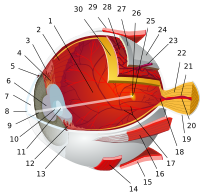

Cross-section of the human eye, showing the position of the pupil. | |

| Details | |

| Part of | Eye |

| System | Visual system |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | pupilla. (plural: pupillae) |

| MeSH | D011680 |

| TA98 | A15.2.03.028 |

| TA2 | 6754 |

| FMA | 58252 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The pupil is a hole located in the center of the iris of the eye that allows light to strike the retina.[1] It appears black because light rays entering the pupil are either absorbed by the tissues inside the eye directly, or absorbed after diffuse reflections within the eye that mostly miss exiting the narrow pupil.[citation needed] The size of the pupil is controlled by the iris, and varies depending on many factors, the most significant being the amount of light in the environment. The term "pupil" was coined by Gerard of Cremona.[2]

In humans, the pupil is circular, but its shape varies between species; some cats, reptiles, and foxes have vertical slit pupils, goats and sheep have horizontally oriented pupils, and some catfish have annular types.[3] In optical terms, the anatomical pupil is the eye's aperture and the iris is the aperture stop. The image of the pupil as seen from outside the eye is the entrance pupil, which does not exactly correspond to the location and size of the physical pupil because it is magnified by the cornea. On the inner edge lies a prominent structure, the collarette, marking the junction of the embryonic pupillary membrane covering the embryonic pupil.

Function

The iris is a contractile structure, consisting mainly of smooth muscle, surrounding the pupil. Light enters the eye through the pupil, and the iris regulates the amount of light by controlling the size of the pupil. This is known as the pupillary light reflex.

The iris contains two groups of smooth muscles; a circular group called the sphincter pupillae, and a radial group called the dilator pupillae. When the sphincter pupillae contract, the iris decreases or constricts the size of the pupil. The dilator pupillae, innervated by sympathetic nerves from the superior cervical ganglion, cause the pupil to dilate when they contract. These muscles are sometimes referred to as intrinsic eye muscles.

The sensory pathway (rod or cone, bipolar, ganglion) is linked with its counterpart in the other eye by a partial crossover of each eye's fibers. This causes the effect in one eye to carry over to the other.

Effect of light

The pupil gets wider in the dark and narrower in light. When narrow, the diameter is 2 to 4 millimeters. In the dark it will be the same at first, but will approach the maximum distance for a wide pupil 3 to 8 mm. However, in any human age group there is considerable variation in maximal pupil size. For example, at the peak age of 15, the dark-adapted pupil can vary from 4 mm to 9 mm with different individuals. After 25 years of age, the average pupil size decreases, though not at a steady rate.[4][5] At this stage the pupils do not remain completely still, therefore may lead to oscillation, which may intensify and become known as hippus. The constriction of the pupil and near vision are closely tied. In bright light, the pupils constrict to prevent aberrations of light rays and thus attain their expected acuity; in the dark, this is not necessary, so it is chiefly concerned with admitting sufficient light into the eye.[6]

When bright light is shone on the eye, light-sensitive cells in the retina, including rod and cone photoreceptors and melanopsin ganglion cells, will send signals to the oculomotor nerve, specifically the parasympathetic part coming from the Edinger-Westphal nucleus, which terminates on the circular iris sphincter muscle. When this muscle contracts, it reduces the size of the pupil. This is the pupillary light reflex, which is an important test of brainstem function. Furthermore, the pupil will dilate if a person sees an object of interest.[citation needed]

Clinical significance

Effect of drugs

If the drug pilocarpine is administered, the pupils will constrict and accommodation is increased due to the parasympathetic action on the circular muscle fibers, conversely, atropine will cause paralysis of accommodation (cycloplegia) and dilation of the pupil.

Certain drugs cause constriction of the pupils, such as opioids.[7] Other drugs, such as atropine, LSD, MDMA, mescaline, psilocybin mushrooms, cocaine and amphetamines may cause pupil dilation.[8][9]

The sphincter muscle has a parasympathetic innervation, and the dilator has a sympathetic innervation. In pupillary constriction induced by pilocarpine, not only is the sphincter nerve supply activated but that of the dilator is inhibited. The reverse is true, so control of pupil size is controlled by differences in contraction intensity of each muscle.

Another term for the constriction of the pupil is miosis. Substances that cause miosis are described as miotic. Dilation of the pupil is mydriasis. Dilation can be caused by mydriatic substances such as an eye drop solution containing tropicamide.

Diseases

A condition called bene dilitatism occurs when the optic nerves are partially damaged. This condition is typified by chronically widened pupils due to the decreased ability of the optic nerves to respond to light. In normal lighting, people affected by this condition normally have dilated pupils, and bright lighting can cause pain. At the other end of the spectrum, people with this condition have trouble seeing in darkness. It is necessary for these people to be especially careful when driving at night due to their inability to see objects in their full perspective. This condition is not otherwise dangerous.

Size

The size of the pupil (often measured as diameter) can be a symptom of an underlying disease. Dilation of the pupil is known as mydriasis and contraction as miosis.

Not all variations in size are indicative of disease however. In addition to dilation and contraction caused by light and darkness, it has been shown that solving simple multiplication problems affects the size of the pupil.[10] The simple act of recollection can dilate the size of the pupil,[11] however when the brain is required to process at a rate above its maximum capacity, the pupils contract.[12] There is also evidence that pupil size is related to the extent of positive or negative emotional arousal experienced by a person.[13]

Myopic individuals have larger resting and dark dilated pupils than hyperopic and emmetropic individuals, likely due to requiring less accommodation (which results in pupil constriction).[14]

Some humans are able to exert direct control over their iris muscles, giving them the ability to manipulate the size of their pupils (i.e. dilating and constricting them) on command, without any changes in lighting condition or eye accommodation state.[15] However, this ability is likely very rare and its purpose or advantages over those without it are unclear.

Animals

Not all animals have circular pupils. Some have slits or ovals which may be oriented vertically, as in crocodiles, vipers, cats and foxes, or horizontally as in some rays, flying frogs, mongooses and artiodactyls such as elk, red deer, reindeer and hippopotamus, as well as the domestic horse. Goats, sheep, toads and octopus pupils tend to be horizontal and rectangular with rounded corners. Some skates and rays have crescent shaped pupils,[16] gecko pupils range from circular, to a slit, to a series of pinholes,[17] and the cuttlefish pupil is a smoothly curving W shape. Although human pupils are normally circular, abnormalities like colobomas can result in unusual pupil shapes, such as teardrop, keyhole or oval pupil shapes.

There may be differences in pupil shape even between closely related animals. In felids, there are differences between small- and large eyed species. The domestic cat (Felis sylvestris domesticus) has vertical slit pupils, its large relative the Siberian tiger (Panthera tigris altaica) has circular pupils and the Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx) is intermediate between those of the domestic cat and the Siberian tiger. A similar difference between small and large species may be present in canines. The small red fox (Vulpes vulpes) has vertical slit pupils whereas their large relatives, the gray wolf (Canis lupus lupus) and domestic dogs (Canis lupus familiaris) have round pupils.[citation needed]

Evolution and adaptation

One explanation for the evolution of slit pupils is that they can exclude light more effectively than a circular pupil.[citation needed] This would explain why slit pupils tend to be found in the eyes of animals with a crepuscular or nocturnal lifestyle that need to protect their eyes during daylight. Constriction of a circular pupil (by a ring-shaped muscle) is less complete than closure of a slit pupil, which uses two additional muscles that laterally compress the pupil.[18] For example, the cat's slit pupil can change the light intensity on the retina 135-fold compared to 10-fold in humans.[19] However, this explanation does not account for circular pupils that can be closed to a very small size (e.g., 0.5 mm in the tarsier) and the rectangular pupils of many ungulates which do not close to a narrow slit in bright light.[20] An alternative explanation is that a partially constricted circular pupil shades the peripheral zones of the lens which would lead to poorly focused images at relevant wavelengths. The vertical slit pupil allows for use of all wavelengths across the full diameter of the lens, even in bright light.[3] It has also been suggested that in ambush predators such as some snakes, vertical slit pupils may aid in camouflage, breaking up the circular outline of the eye.[21]

Activity pattern and behavior

In a study of Australian snakes, pupil shapes correlated both with diel activity times and with foraging behavior. Most snake species with vertical pupils were nocturnal and also ambush foragers, and most snakes with circular pupils were diurnal and active foragers. Overall, foraging behaviour predicted pupil shape accurately in more cases than did diel time of activity, because many active-foraging snakes with circular pupils were not diurnal. It has been suggested that there may be a similar link between foraging behaviour and pupil shape amongst the felidae and canidae discussed above.[21]

A 2015 study[22] confirmed the hypothesis that elongated pupils have increased dynamic range, and furthered the correlations with diel activity. However it noted that other hypotheses could not explain the orientation of the pupils. They showed that vertical pupils enable ambush predators to optimise their depth perception, and horizontal pupils to optimise the field of view and image quality of horizontal contours. They further explained why elongated pupils are correlated with the animal's height.

- Animals with non-circular pupils

-

A goat with horizontal rectangular pupils

-

A stingray with crescent pupils

-

A crocodile with thin vertical slit pupils

-

A cuttlefish with W-shaped pupils

-

A gecko with 'thin string of pearls' pupils

-

A cat with thick vertical slit pupils

Society and culture

The pupil plays a role in eye contact and nonverbal communication. The voluntary or involuntary enlargement or dilation of the pupils indicates cognitive arousal, interest in the subject of attention, and/or sexual arousal. On the other hand, when the pupil is voluntarily or involuntarily contracted, it could indicate the opposite - disinterest or disgust. Exceptionally large or dilated pupils are also perceived to be an attractive feature in body language.[23]

In a surprising number of unrelated languages, the etymological meaning of the term for pupil is "little person".[24][25] This is true, for example, of the word pupil itself: this comes into English from Latin pūpilla, which means "doll, girl", and is a diminutive form of pupa, "girl". (The double meaning in Latin is preserved in English, where pupil means both "schoolchild" and "dark central portion of the eye within the iris".)[26] This may be because the reflection of one's image in the pupil is a minuscule version of one's self.[24] In the Old Babylonian period (c. 1800-1600 BC) in ancient Mesopotamia, the expression "protective spirit of the eye" is attested, perhaps arising from the same phenomenon.

The English phrase apple of my eye arises from an Old English usage, in which the word apple meant not only the fruit but also the pupil or eyeball.[27]

See also

- Pupillary response

- Pupil function

- Dilated fundus examination

- Eye contact

- Horner's syndrome

- Mydriasis

- Synechia (eye)

- Anisocoria

- Adie's pupil

- Argyll Robertson pupil

- Light-near dissociation

- Marcus Gunn Pupil

References

- ^ Cassin, B. and Solomon, S. (1990) Dictionary of Eye Terminology. Gainesville, Florida: Triad Publishing Company.

- ^ Arráez-Aybar, Luis-A (2015). "Toledo School of Translators and their influence on anatomical terminology". Annals of Anatomy - Anatomischer Anzeiger. 198: 21–33. doi:10.1016/j.aanat.2014.12.003. PMID 25667112.

- ^ a b Malmström T, Kröger RH (January 2006). "Pupil shapes and lens optics in the eyes of terrestrial vertebrates". J. Exp. Biol. 209 (Pt 1): 18–25. doi:10.1242/jeb.01959. PMID 16354774.

- ^ "Aging Eyes and Pupil Size". Amateurastronomy.org. Archived from the original on 2013-10-23. Retrieved 2013-08-28.

- ^ Winn, B.; Whitaker, D.; Elliott, D. B.; Phillips, N. J. (March 1994). "Factors Affecting Light-Adapted Pupil Size in Normal Human Subjects" (PDF). Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 35 (3): 1132–1137. PMID 8125724. Retrieved 2013-08-28.

- ^ "Sensory Reception: Human Vision: Structure and Function of the Eye" Encyclopædia Brtiannicam Chicago, 1987

- ^ Larson, Merlin D. (2008-06-01). "Mechanism of opioid-induced pupillary effects". Clinical Neurophysiology. 119 (6): 1358–64. doi:10.1016/j.clinph.2008.01.106. PMID 18397839. S2CID 9591926.

- ^ Johnson, Michael D. (October 1, 1999). "How to spot illicit drug abuse in your patients" (PDF). Postgraduate Medicine. 106 (4): 199–200, 203–6, 211–4 passim. doi:10.3810/pgm.1999.10.1.721. PMID 10533519. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- ^ Alderman, Elizabeth M.; Schwartz, Brian (1997-06-01). "Substances of Abuse". Pediatrics in Review. 18 (6): 204–215. doi:10.1542/pir.18-6-204. S2CID 73382801.

- ^ Hess, Eckhard H.; Polt, James M. (1964-03-13). "Pupil Size in Relation to Mental Activity during Simple Problem-Solving". Science. 143 (3611): 1190–2. Bibcode:1964Sci...143.1190H. doi:10.1126/science.143.3611.1190. PMID 17833905. S2CID 27169110.

- ^ L. Andreassi, John (2006). Psychophysiology: Human Behavior and Physiological Response (Psychophysiology: Human Behavior & Physiological Response) (5th ed.). Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0805849516.

- ^ "My Brain is Overloaded". prezi.com. Retrieved 2017-02-28.

- ^ Partala, T. & Surakka, V. (2003). "Pupil size variation as an indication of affective processing". International Journal of Human-Computer Studies. 59 (1–2): 185–198. doi:10.1016/S1071-5819(03)00017-X. S2CID 7007209.

- ^ Cakmak, Hasan Basri; Cagil, Nurullah; Simavlı, Hüseyin; Duzen, Betul; Simsek, Saban (February 2010). "Refractive Error May Influence Mesopic Pupil Size". Current Eye Research. 35 (2): 130–136. doi:10.3109/02713680903447892. ISSN 0271-3683. PMID 20136423. S2CID 27407880.

- ^ Eberhardt, Lisa V.; Grön, Georg; Ulrich, Martin; Huckauf, Anke; Strauch, Christoph (2021-10-01). "Direct voluntary control of pupil constriction and dilation: Exploratory evidence from pupillometry, optometry, skin conductance, perception, and functional MRI". International Journal of Psychophysiology. 168: 33–42. doi:10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2021.08.001. ISSN 0167-8760. PMID 34391820.

- ^ Murphy, C.J. & Howland, H.C. (1990). "The functional significance of crescent-shaped pupils and multiple pupillary apertures". Journal of Experimental Zoology. 256 (S5): 22. Bibcode:1990JEZ...256S..22M. doi:10.1002/jez.1402560505.

- ^ Roth, Lina S. V.; Lundström, Linda; Kelber, Almut; Kröger, Ronald H. H.; Unsbo, Peter (2009-03-01). "The pupils and optical systems of gecko eyes". Journal of Vision. 9 (3): 27.1–11. doi:10.1167/9.3.27. PMID 19757966.

- ^ Walls, G.L. (1967) [1942]. The vertebrate eye and its adaptive radiation. Cranbrook Institute of Science Bulletin. Vol. 19. Hafner. OCLC 10363617.

- ^ Hughes, A. (2013) [1977]. "The topography of vision in mammals of contrasting life style: comparative optics and retinal organisation". In Crescitelli, F. (ed.). The Visual System in Vertebrates. Handbook of Sensory Physiology. Vol. 7/5. Springer. pp. 613–756. ISBN 978-3-642-66468-7.

- ^ Land, M.F. (2006). "Visual optics: the shapes of pupils". Current Biology. 16 (5): R167–8. Bibcode:2006CBio...16.R167L. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2006.02.046. PMID 16527734.

- ^ a b Brischoux, F., Pizzatto, L. and Shine, R. (2010). "Insights into the adaptive significance of vertical pupil shape in snakes". Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 23 (9): 1878–85. doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2010.02046.x. PMID 20629855.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Banks, Martin S.; Sprague, William W.; Schmoll, Jürgen; Parnell, Jared A. Q.; Love, Gordon D. (2015). "Why do animal eyes have pupils of different shapes?". Science Advances. 1 (7): e1500391. Bibcode:2015SciA....1E0391B. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1500391. PMC 4643806. PMID 26601232.

- ^ Tombs, Selina; Silverman, Irwin (2004-07-01). "Pupillometry: A sexual selection approach". Evolution and Human Behavior. 25 (4): 221–228. Bibcode:2004EHumB..25..221T. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2004.05.001. ISSN 1090-5138.

- ^ a b Brown, Donald E. (2004). "Human Universals, Human Nature & Human Culture". Daedalus. 133 (4): 49. doi:10.1162/0011526042365645. JSTOR 20027944. S2CID 8522764.

- ^ Brown, Cecil H.; Witkowski, Stanley R. (1981). "Figurative Language in a Universalist Perspective". American Ethnologist. 8 (3): 596–615. doi:10.1525/ae.1981.8.3.02a00110. JSTOR 644304.

- ^ "pupil, n.2.", Oxford English Dictionary Online, 3rd. edn (Oxford University Press, 2007).

- ^ apple, n.", Oxford English Dictionary Online, 3rd ed. (Oxford University Press, 2008), § 6 B.

External links

- Atlas image: eye_1 at the University of Michigan Health System — "Sagittal Section Through the Eyeball"

- Atlas image: eye_2 at the University of Michigan Health System — "Sagittal Section Through the Eyeball"

- A pupil examination simulator, demonstrating the changes in pupil reactions for various nerve lesions.