Sierra de las Nieves National Park

| Sierra de las Nieves National Park | |

|---|---|

| Parque Nacional de la Sierra de las Nieves | |

| |

Location of Sierra de las Nieves | |

| Location | Province of Málaga, Spain |

| Nearest city | Tolox |

| Coordinates | 36°41′00″N 05°00′00″W / 36.68333°N 5.00000°W |

| Area | 93,930 ha (362.7 sq mi) |

| Established | July 28, 1989 |

| Visitors | 100,000 |

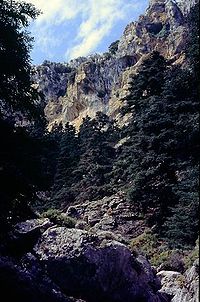

The Sierra de las Nieves National Park (Spanish: Parque Nacional de la Sierra de las Nieves) is a national park in the Sierra de las Nieves range, Andalusia, southern Spain. It is located behind Marbella and to the east of the road to Ronda from the Costa del Sol. In 2019, the Council of Ministers proposed to Parliament the transformation of the Natural Park into a National Park.[1] On 1 July 2021, King Felipe VI gave royal assent to the Sierra de las Nieves National Park Act, which declares it as a National Park.[2]

Sierra de las Nieves stands out for the great variety of landscapes and ecosystems it boasts and this is due to the complex geology and geomorphology it presents, as well as the special climatic conditions to which it is exposed.

The true hallmark of this territory are the Spanish fir forests, a botanical relic of the Tertiary conifer forests, endemic to the mountain ranges of Malaga and Cadiz, and which have in this protected natural area their largest area of distribution in the world with nearly 2,000 hectares.[3]

Caves

[edit]There are a considerable number of large caves in the park, several taking the traditional form of horizontal caverns. Three are of particular interest,[according to whom?] namely Hoyos del Pilar, Hoyos de Lifa and Cuevas del Moro.

The area is known for its shafts. One of these, GESM, is one of the deepest in Europe and was named after the Grupo de Exploraciones Subterráneas de Málaga (GESM) which explored it in September 1978. The entrance to this shaft is located at 1670 m and descends 1098 m with a few large drops. The Gran Pozo drops 115 m and the Pozo Paco de la Torre has a vertical fall of 194 m. At a depth of 900 m there are some interesting rock formations in the Sala de Maravillas, and Lake Ere is located almost at the bottom. It has still[when?] not been fully explored.

Sima de la Tinaja is located in the area of the Tajo de la Caina at an altitude of 760 m. It is 54 m deep. It can be reached from Tolox. Many prehistoric artefacts have been recovered from this cave and many are to be found in the Málaga Museum.

Some of the other shafts are mentioned here. The list is by no means exclusive and many are surely yet to be discovered.

- Sima Honda is located at an altitude of 1640 m and drops to a depth of 133 m and is formed from two vertical wells of 52 m and 80 m.

- Sima de Horcajuelos is located at an altitude of 1600 m, dropping only 22 m.

- Sima Bambi is near GESM and drops 7 m.

- Sima de las Grajas is located 500 m from the Quejigales recreation area and is 10 m deep.

- Sima de la Espalda is located near Hoyos de Pilar at 1750 m altitude and drops 38 m.

- Sima Erotica, located near Hoyo de las Pilones, is 103 m deep with various drops, one of which is 53 m.

- Complejo Raya Heleda located near Hoyos de Pilar is 57 m deep.

- Sima de las Palomas located near Hoyos de Pilar is 56 m deep.

Tourism

[edit]There is a network of accommodation and tourist services that allow it to be visited comfortably and enjoy its beauty.

The national park has an extensive network of paths and trails that allow hiking, although the scarcity of water sources in the area should be taken into account. There are two main accesses that lead to the heart of the park: one from the Ronda road to San Pedro de Alcántara, along a forest track that leads to the Los Quejigales recreational area, and another from Yunquera along a forest track that reaches the Pº Saucillo viewpoints, and Caucón or Luis Ceballos. There are also accesses through the town of Tolox, Istán and El Burgo. The main routes of the national park are Quejigales-Torrecilla and Pº Saucillo-Torrecilla which lead to the highest peak in western Andalusia. Another popular path is the Mirador Ceballos-Tajo de la Caína, which leads to the Pinsapar de Caucón and allows you to observe the impressive landscapes that exist from the Tajo de la Caína.[4]

The towns of the region also have many places to visit and stand out for their historical heritage and for their unique festivals, such as the Polvos and the Cohetá de Tolox, the Alozaina Flour Carnival, the Siete Ramales Soup and the Quema de Judas in El Burgo or Corpus Christi in Yunquera.

Threats

[edit]Overgrazing has been one of the main causes that has hindered the regeneration of many areas, a threat that has decreased with the regulation of livestock use. It is widely accepted that moderate loads do not reduce, and even stimulate, pasture productivity, maintain high levels of biological diversity, and reduce fire risk. However, the overload of livestock in the mountains leads to the reduction of plant cover and the simplification of its structure and composition, seriously damaging the natural regeneration of tree and shrub species. In fact, overgrazing is responsible for the strong erosion suffered by the highest areas of the sierra, preventing the regeneration of the high mountain gall oak.[5]

Another important threat factor is derived from climate change. High temperatures and prolonged droughts will enhance the negative effects of forest fires, pests and diseases in the future and consequently increase the risk of soil erosion. The latter can be seen equally intensified as a result of the increase in the irregularity and torrentiality of precipitation and the topography of the area. In addition, studies carried out reflect a reduction in the potential habitat of the Spanish fir at the end of the 21st century.[6]

In relation to forest pests and diseases, the fungi Heterobasidium annosum and Armillaria mellea, together with the lepidoptera Dioryctria aulloi and the borer Cryphalus numidicus have caused numerous damages to the Spanish fir during the last decades. It is considered likely that its expansion has been favored by the weakening of plant formations as a result, among other things, of periods of drought, although currently the phytosanitary status of the Spanish firs has reached an “ecological balance”. The Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, Fisheries and Sustainable Development is carrying out a Pinsapo Recovery Plan9 through which conservation actions are being carried out, which began in the mid-20th century and culminated in 2011 with the approval of said plan, consisting of the protection and improvement of the existing populations, as well as the restoration of their habitat, attempting to regenerate and reforest the areas in which they have disappeared as a result of the forest fires.[7]

References

[edit]- ^ "El BOE publica la aprobación de la propuesta de declaración del Parque Nacional de la Sierra de las Nieves". Diario Sur (in Spanish). 8 January 2019. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- ^ "Ley 9/2021, de 1 de julio, de declaración del Parque Nacional de la Sierra de las Nieves". boe.es (in Spanish). 3 July 2021.

- ^ "Decreto 162/2018, de 4 de septiembre, por el que se aprueban el Plan de Ordenación de los Recursos Naturales del ámbito de Sierra de las Nieves y el Plan Rector de Uso y Gestión del Parque Natural Sierra de las Nieves".

- ^ Sánchez, Nacho (2019-01-30). "Bosques prehistóricos y pueblos blancos en la sierra de las Nieves". EL PAÍS (in Spanish). Retrieved 2022-05-15.

- ^ Alvarez Calvente (1996). "Repoblaciones y trabajos de regeneración en el Pinsapar de la Sierra de las Nieves".

- ^ J. C. Linares • J. A. Carreira • V. Ochoa (2011). "Human impacts drive forest structure and diversity. Insights from Mediterranean mountain forest dominated by Abies pinsapo (Boiss.)".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Plan de Recuperación del Pinsapo