Christian Bale

Christian Bale | |

|---|---|

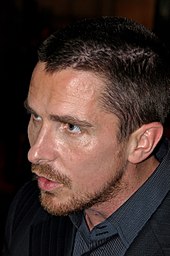

Bale in 2019 | |

| Born | Christian Charles Philip Bale 30 January 1974 Haverfordwest, Wales |

| Citizenship |

|

| Occupation | Actor |

| Years active | c. 1982–present |

| Works | Full list |

| Spouse |

Sibi Blazic (m. 2000) |

| Children | 2 |

| Father | David Bale |

| Relatives | Gloria Steinem (stepmother) |

| Awards | Full list |

| Signature | |

| |

Christian Charles Philip Bale (born 30 January 1974) is an English actor. Known for his versatility and physical transformations for his roles, he has been a leading man in films of several genres. He has received various accolades, including an Academy Award and two Golden Globe Awards. Forbes magazine ranked him as one of the highest-paid actors in 2014.

Born in Wales to English parents, Bale had his breakthrough role at age 13 in Steven Spielberg's 1987 war film Empire of the Sun. After more than a decade of performing in leading and supporting roles in films, he gained wider recognition for his portrayals of serial killer Patrick Bateman in the black comedy American Psycho (2000) and the title role in the psychological thriller The Machinist (2004). In 2005, he played superhero Batman in Batman Begins and again in The Dark Knight (2008) and The Dark Knight Rises (2012), garnering acclaim for his performance in the trilogy, which is one of the highest-grossing film franchises.

Bale continued in starring roles in a range of films outside his work as Batman, including the period drama The Prestige (2006), the action film Terminator Salvation (2009), the crime drama Public Enemies (2009), the epic film Exodus: Gods and Kings (2014) and the superhero film Thor: Love and Thunder (2022). For his portrayal of boxer Dicky Eklund in the 2010 biographical film The Fighter, he won an Academy Award and a Golden Globe Award. Further Academy Award and Golden Globe Award nominations came for his work in the black comedy American Hustle (2013) and the biographical dramedies The Big Short (2015) and Vice (2018). His performances as politician Dick Cheney in Vice and race car driver Ken Miles in the sports drama Ford v Ferrari (2019) earned him a second win and a fifth nomination respectively at the Golden Globe Awards.

Early life

Christian Charles Philip Bale[1] was born on 30 January 1974 in Haverfordwest, Pembrokeshire, to English parents—Jenny James, a circus performer, and David Bale, an entrepreneur and activist.[2][3][4] Bale has remarked, "I was born in Wales but I'm not Welsh—I'm English."[5] He has two elder sisters, Sharon and Louise, and a half-sister from his father's first marriage, Erin.[4] One of his grandfathers was a comedian while the other was a stand-in for John Wayne.[6] Bale and his family left Wales when he was two years old,[7] and after living in Portugal and Oxfordshire, England, they settled in Bournemouth.[8] As well as saying that the family had lived in 15 towns by the time he was 15, Bale described the frequent relocation as being driven by "necessity rather than choice" and acknowledged that it had a major influence on his career selection.[7][9][10] He attended Bournemouth School, later saying he left school at age 16.[11][12] Bale's parents divorced in 1991, and at age 17, he moved with his sister Louise and their father to Los Angeles.[13]

Bale trained in ballet as a child.[14] His first acting role came at eight years old in a commercial for the fabric softener Lenor.[15] He also appeared in a Pac-Man cereal commercial.[16] After his sister was cast in a West End musical, Bale considered taking up acting professionally.[17] He said later he did not find acting appealing but pursued it at the request of those around him because he had no reason not to do so.[18] After participating in school plays, Bale performed opposite Rowan Atkinson in the play The Nerd in the West End in 1984.[12][15] He did not undergo any formal acting training.[12]

Career

Early roles and breakthrough (1986–1999)

After deciding to become an actor at age ten, Bale secured a minor role in the 1986 television film Anastasia: The Mystery of Anna. Its star, Amy Irving, who was married to director Steven Spielberg, subsequently recommended Bale for Spielberg's 1987 film Empire of the Sun.[19] At age 13, Bale was chosen from over 4,000 actors to portray a British boy in a World War II Japanese internment camp.[20] For the film, he spoke with an upper-class cadence without the help of a dialogue coach.[21] The role propelled Bale to fame,[22] and his work earned him acclaim and the inaugural Best Performance by a Juvenile Actor Award from the National Board of Review of Motion Pictures.[23] Earlier in the same year, he starred in the fantasy film Mio in the Land of Faraway, based on the novel Mio, My Son by Astrid Lindgren.[24][25] The fame from Empire of the Sun led to Bale being bullied in school and finding the pressures of working as an actor unbearable.[26] He grew distrustful of the acting profession because of media attention but said that he felt obligated at a young age to continue to act for financial reasons.[22] Around this time, actor and filmmaker Kenneth Branagh persuaded Bale to appear in his film Henry V in 1989, which drew him back into acting.[23] The following year, Bale played Jim Hawkins opposite Charlton Heston as Long John Silver in Treasure Island, a television film adaptation of Robert Louis Stevenson's book of the same name.[27]

Bale starred in the 1992 Disney musical film Newsies, which was unsuccessful both at the box office and with critics.[28] Rebecca Milzoff of Vulture revisited the film in 2012 and found the cracks in Bale's voice during his performance of the song "Santa Fe" charming and apt even though he was not a great singer.[29] In 1993, he appeared in Swing Kids, a film about teenagers who secretly listen to forbidden jazz during the rise of Nazi Germany.[30] In Gillian Armstrong's 1994 film Little Women, Bale played Theodore "Laurie" Laurence following a recommendation from Winona Ryder, who starred as Jo March.[23] The film achieved critical and commercial success.[31] Of Bale's performance, Ryder said he captured the complex nature of the role.[31] He next voiced Thomas, a young compatriot of Captain John Smith, in the 1995 Disney animated film Pocahontas, which attracted a mixed critical reception.[32][33] Bale played a small part in the 1996 film The Portrait of a Lady, based on the Henry James novel of the same name,[34] and appeared in the 1998 musical film Velvet Goldmine, set in the 1970s during the glam rock era.[35] In 1999, he was part of an ensemble cast, which included Kevin Kline and Michelle Pfeiffer, portraying Demetrius in A Midsummer Night's Dream, a film adaptation of William Shakespeare's play of the same name.[36]

Rise to prominence and commercial decline (2000–2004)

Bale played Patrick Bateman, an investment banker and serial killer, in American Psycho, a film adaptation of Bret Easton Ellis's novel of the same name, directed by Mary Harron. While Harron had chosen Bale for the part, the film's production and distribution company, Lionsgate, originally disagreed and hired Leonardo DiCaprio to play Bateman with Oliver Stone to direct. Bale and Harron were brought back after DiCaprio and Stone had left the project.[37][38] Bale exercised and tanned himself for months to achieve Bateman's chiseled physique and had his teeth capped to assimilate to the character's narcissistic nature.[39][40] American Psycho premiered at the 2000 Sundance Film Festival. Harron said critic Roger Ebert named it the most hated film at the event.[41] Of Bale's work, Ebert wrote he "is heroic in the way he allows the character to leap joyfully into despicability; there is no instinct for self-preservation here, and that is one mark of a good actor."[42] The film was released in April 2000, becoming a commercial and critical success and later developing a cult following;[43][44] the role established Bale as a leading man.[15][45]

In the four years that followed American Psycho, Bale's career experienced critical and commercial failure.[46] He next played a villainous real estate heir in John Singleton's action film Shaft and appeared in John Madden's film adaptation of the Louis de Bernières novel Captain Corelli's Mandolin as Mandras, a Greek fisherman who vies with Nicolas Cage's title character for the affections of Pelagia, played by Penélope Cruz.[34] Bale said he found it refreshing to play Mandras, who is emotionally humane, after working on American Psycho and Shaft.[47] In 2002, he appeared in three films: Laurel Canyon, Reign of Fire and Equilibrium.[23] Reviewing Laurel Canyon for Entertainment Weekly, Lisa Schwarzbaum called Bale's performance "fussy".[48] After having reservations about joining the post-apocalyptic Reign of Fire, which involved computer-generated imagery, Bale professed his enjoyment of making films that could go awry and cited director Rob Bowman as a reason for his involvement.[49][50] In Equilibrium, he plays a police officer in a futuristic society and performs gun kata, a fictional martial art that incorporates gunfighting.[34][51][52] IGN's Jeff Otto characterised Reign of Fire as "poorly received" and Equilibrium as "highly underrated", while The Independent's Stephen Applebaum described the two films along with Shaft and Captain Corelli's Mandolin as "mediocre fare".[53][54]

Bale starred as the insomnia-ridden, emotionally dysfunctional title character in the psychological thriller The Machinist. To prepare for the role, he initially only smoked cigarettes and drank whiskey. His diet later expanded to include black coffee, an apple and a can of tuna per day.[55][56] Bale lost 63 pounds (29 kg), weighing 121 pounds (55 kg) to play the character, who was written in the script as "a walking skeleton".[57] His weight loss prompted comparisons with Robert De Niro's weight gain in preparation to play Jake LaMotta in the 1980 film Raging Bull.[58] Describing his transformation as mentally calming, Bale claimed he had stopped working for a while because he did not come upon scripts that piqued his interest and that the film's script drew him to lose weight for the part.[59][60] The Machinist was released in October 2004; it performed poorly at the box office.[57] Roger Moore of the Orlando Sentinel regarded it as one of the best films of the year, and Todd McCarthy of Variety wrote that Bale's "haunted, aggressive and finally wrenching performance" gave it a "strong anchor".[61][62]

Batman and dramatic roles (2005–2008)

Bale portrayed American billionaire Bruce Wayne and his superhero alias Batman in Christopher Nolan's Batman Begins, a reboot of the Batman film series. Nolan cast Bale, who was still fairly unknown at the time, because Bale had "exactly the balance of darkness and light" Nolan sought.[63][64] For the part, Bale regained the weight he lost for The Machinist and built muscle, weighing 220 pounds (100 kg).[65] He trained in weapons, Wing Chun Kung Fu and the Keysi Fighting Method.[66] Acknowledging the story's peculiar circumstances involving a character "who thinks he can run around in a batsuit in the middle of the night", Bale said he and Nolan had deliberately approached it with "as realistic a motivation as possible", referencing Wayne's parents' murder.[54] Bale voiced Wayne and Batman differently. He employed gravelly tone qualities for Batman, which Nolan believed reinforced the character's visual appearance.[67] Batman Begins was released in the US in June 2005.[68] Tim Grierson and Will Leitch of Vulture complimented Bale's "sensitive, intelligent portrayal of a spoiled, wayward Bruce who finally grows up (and fights crime)."[34] The performance earned Bale the MTV Movie Award for Best Hero.[69]

In the same year, Bale voiced the titular Howl, a wizard, in the English-language dub of Hayao Miyazaki's Howl's Moving Castle, a Japanese animated film adaptation of Diana Wynne Jones's novel of the same name.[70] He committed himself to voice the role after watching Miyazaki's animated film Spirited Away.[71] Later that year, he starred as a US war veteran who deals with post-traumatic stress disorder in the David Ayer-helmed crime drama Harsh Times, which premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival.[34][72] He portrayed colonist John Rolfe in The New World, a historical drama film inspired by the stories of Pocahontas, directed by Terrence Malick. The film was released on 25 December 2005.[73] The following year saw the premiere of Rescue Dawn, by German filmmaker Werner Herzog, in which Bale portrayed US fighter pilot Dieter Dengler, who fights for his life after being shot down while on a mission during the Vietnam War.[34] After the two worked together, Herzog stated that he had considered Bale to be among his generation's greatest talents long before he played Batman.[74] The Austin Chronicle's Marjorie Baumgarten viewed Bale's work as a continuance of his "masterful command of yet another American personality type."[75]

For the 2006 film The Prestige, Bale reunited with Batman Begins director Nolan, who said that Bale was cast after offering himself for the part. It is based on the novel of the same name by Christopher Priest about a rivalry between two Victorian era magicians, whom Bale and Hugh Jackman play in the film.[76][77] While it attracted acclaim from critics, the film performed more modestly during its run in theatres, earning $110 million against a $40 million budget.[78][79][80] In his review for The New York Times, A. O. Scott highlighted Bale's "fierce inwardness" and called his performance "something to savor".[81] Bale next starred in the 2007 drama films I'm Not There, portraying two incarnations of singer-songwriter Bob Dylan, and in 3:10 to Yuma, playing a justice-seeking cattleman. He characterised his Dylan incarnations as "two men on a real quest for truth" and attributed his interest in 3:10 to Yuma to his affinity for films where he gets to "just be dirty and crawling in the mud".[82][83] Bale reprised the role of Batman in Nolan's Batman Begins sequel The Dark Knight, which received acclaim and became the fourth film to gross more than $1 billion worldwide upon its July 2008 release.[84][85] He did many of his own stunts, including one that involved standing on the roof of the Sears Tower in Chicago.[86] The Dark Knight has been regarded by critics as the best superhero film.[87][88]

The Dark Knight trilogy completion and acclaim (2009–2012)

In February 2008, Warner Bros. announced that Bale would star as rebellion leader John Connor in the post-apocalyptic action film Terminator Salvation,[89] directed by McG, who cited Bale as "the most credible actor of his generation".[90] In February 2009, an audio recording of a tirade on the film's set in July 2008 involving Bale was released. It captured him directing profanities towards and threatening to attack the film's cinematographer Shane Hurlbut, who walked onto the set during the filming of a scene acted by Bale and Bryce Dallas Howard, and culminated in Bale threatening to quit the film if Hurlbut was not fired.[91][92] Several colleagues in the film industry defended Bale, attributing the incident to his dedication to acting.[91][93][94] Bale publicly apologised in February 2009, calling the outburst "inexcusable" and his behaviour "way out of order" and affirming to have made amends with Hurlbut.[95][96] Terminator Salvation was released in May 2009 to tepid reviews.[97][98] Claudia Puig of USA Today considered Bale's work to be "surprisingly one-dimensional", while The Age's Jake Wilson wrote he gave one of his least compelling performances.[99][100] Bale later admitted he knew during production that the film would not revitalise the Terminator franchise as he had wished.[101] He asserted he would not work with McG again.[98]

Bale portrayed FBI agent Melvin Purvis opposite Johnny Depp as gangster John Dillinger in Michael Mann's crime drama Public Enemies.[102] Released in July 2009,[103] it earned critical praise and had a commercially successful theatrical run.[104] Dan Zak of The Washington Post was unsatisfied with the casting of Bale and Depp, believing their characters' rivalry lacked electricity, while The New Republic's Christopher Orr found Bale's "characteristically closed off" performance "nonetheless effective".[105][106] The following year, Bale starred in the role of Dicky Eklund, a professional boxer whose career has ended due to his drug addiction, in David O. Russell's drama film The Fighter. It chronicles the relationship between Eklund and his brother and boxing trainee, Micky Ward, played by Mark Wahlberg. To balance Eklund's tragic condition, Bale incorporated humor in his characterisation. The portrayal, for which he lost 30 pounds (14 kg), was acclaimed, the San Francisco Chronicle's Mick LaSalle describing it as "shrewdly observed, physically precise and psychologically acute".[107][108] Bale won the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor and the Golden Globe Award for Best Supporting Actor – Motion Picture for his performance.[109][110] In 2011, he starred in Zhang Yimou's historical drama film The Flowers of War, which was the highest-grossing Chinese film of the year.[111] Critics described it as "nationalistic", "anti-Japanese" and "too long, too melodramatic, too lightweight".[111][112]

Bale played Batman again under Christopher Nolan's direction in the sequel The Dark Knight Rises, released in July 2012.[113] He described Batman in the film as a remorseful recluse in poor mental and physical health, who has surrendered following the events of The Dark Knight.[114] Following the shooting at a midnight showing of the film in Aurora, Colorado, Bale and his wife visited survivors, doctors and first responders at The Medical Center of Aurora as well as a memorial to victims.[115] The Dark Knight Rises was the 11th film to gross more than $1 billion worldwide, surpassing The Dark Knight.[116] Nolan's Batman film series, dubbed the Dark Knight trilogy, is one of the highest-grossing film franchises.[117][118] It is also regarded as one of the best comic book film franchises.[119] Bale's performance in the three films garnered universal acclaim,[15][120] with The Guardian, The Indian Express, MovieWeb, NME and a poll conducted by the Radio Times ranking it as the best portrayal of Batman on film.[121] Bale later revealed his dissatisfaction with his work throughout the trilogy, saying he "didn't quite nail" his part and that he "didn't quite manage" what he had hoped he would as Batman.[122]

Continued critical success (2013–2018)

In 2013, Bale played a steel mill worker in Scott Cooper's thriller Out of the Furnace.[123] Cooper rewrote the film's script with Bale in mind before the two even met and would not proceed with the project without the actor's involvement.[12] Critics commended the film and deemed it an excellent beginning of the next phase in Bale's career after playing Batman,[124][125] with Kristopher Tapley of Variety noting his work in the film was his best.[126] That same year, he starred in American Hustle, which reunited him with David O. Russell after their work on The Fighter.[127] To play con artist Irving Rosenfeld, Bale studied footage of interviews with real-life con artist Mel Weinberg, who served as inspiration for the character.[12] He gained 43 pounds (20 kg), shaved part of his head and adopted a slouched posture, which reduced his height by 3 inches (7.6 cm) and caused him to suffer a herniated disc.[128][129] Russell indicated that Robert De Niro, who appeared in an uncredited role, did not recognise Bale when they were first introduced.[130] Writing for the New York Daily News, Joe Neumaier found Bale's performance to be "sad, funny and riveting".[131] He was nominated for an Academy Award and a Golden Globe Award for his work.[110][132]

Bale portrayed Moses in Ridley Scott's epic film Exodus: Gods and Kings. Released in December 2014, the film faced accusations of whitewashing for the casting of Caucasian actors in Middle Eastern roles. Scott justified casting decisions citing financing needs, Bale stating that Scott had been forthright in getting the film made.[133] Its critical response varied between negative and mixed,[134] and the St. Louis Post-Dispatch's Joe Williams called Bale's performance in the film the most apathetic of his career.[135] Bale appeared in Terrence Malick's drama Knight of Cups, which The Atlantic critic David Sims dubbed a "noble failure".[136] During its premiere at the 65th Berlin International Film Festival in February 2015, he said he filmed the project without having learned any dialogue and that Malick had only given him a character description.[137] Later that year, he starred as Michael Burry, an antisocial hedge fund manager, in Adam McKay's The Big Short, a biographical comedy-drama film about the financial crisis of 2007–08.[34] He used an ocular prosthesis in the film.[138] The Wall Street Journal's Joe Morgenstern found his portrayal "scarily hilarious—or in one-liners and quick takes, deftly edited".[139] The role earned Bale Academy Award and Golden Globe Award nominations for Best Supporting Actor.[140][141]

In the 2016 historical drama The Promise, set during the Armenian Genocide, he played an American journalist who becomes involved in a love triangle with a woman, played by Charlotte Le Bon, and an Armenian medical student, played by Oscar Isaac.[34] Critics disapproved of the film, which accrued a $102 million loss.[142] Reviewing the film for The New York Times, Jeannette Catsoulis wrote that Bale appeared "muffled and indistinct".[143] In Cooper's 2017 film Hostiles, Bale starred as a US Army officer escorting a gravely ill Cheyenne war chief and his family back to their home in Montana. He calls the film "a western with brutal, modern-day resonance" and his character "a bigoted and hate-filled man".[15][144] Bale learned the Cheyenne language while working on the film.[144] Empire critic Dan Jolin considered his performance striking and one of the strongest of his career.[145] In 2018, Bale voiced Bagheera in the adventure film Mowgli: Legend of the Jungle. Rolling Stone's David Fear wrote that his voice work and that of Andy Serkis, who directed the film, "bring the soul as well as sound and fury".[146]

Recent career (2018–present)

For the 2018 biographical comedy drama Vice, written and directed by Adam McKay, Bale underwent a major body transformation once again, as he gained over 40 pounds (18 kg) and shaved his head to portray US Vice President Dick Cheney.[128] He described Cheney, who is reckoned the most influential and loathed vice president in US history, as "quiet and secretive".[147][148] The film reunited Bale with Amy Adams, with whom he had co-starred in The Fighter and American Hustle.[149] It received positive reviews, and The Guardian's Peter Bradshaw commended Bale's "terrifically and in fact rather scarily plausible" Cheney impersonation.[150] Lauded by critics, the performance won Bale the Golden Globe Award for Best Actor – Motion Picture Musical or Comedy and garnered him an Academy Award nomination.[151][152] During his acceptance speech at the 76th Golden Globe Awards, Bale thanked Satan for inspiring his Cheney portrayal, which elicited a response from Cheney's daughter and US Representative Liz Cheney, who stated that Bale ruined his opportunity to play "a real superhero".[153]

Bale portrayed sports car racing driver Ken Miles in the 2019 sports drama Ford v Ferrari, for which he lost 70 pounds (32 kg) after playing Cheney.[154] Directed by James Mangold, the film follows Miles and automotive designer Carroll Shelby, played by Matt Damon, in events surrounding the 1966 24 Hours of Le Mans race.[155] The role earned Bale a fifth Golden Globe Award nomination.[156] While promoting the film, he said he would no longer go through weight fluctuations for roles.[154]

Bale played Gorr the God Butcher, a villain, in the Marvel Cinematic Universe superhero film Thor: Love and Thunder, which was released in July 2022. He cited a character in the music video for the Aphex Twin song "Come to Daddy" as an inspiration for his characterisation of Gorr.[157] Bale's portrayal drew praise from critics, who deemed it "grounded and non-campy".[158] He produced and appeared in David O. Russell's period film Amsterdam and Scott Cooper's thriller The Pale Blue Eye,[159] reuniting with both directors for the third time.[160][161] Amsterdam was released in October 2022, receiving dire reviews and failing at the box office.[162][163] The Pale Blue Eye, adapted from the novel of the same name by Louis Bayard, was released in December 2022, receiving mixed reviews from critics.[159][164] With his involvement in the 2023 Japanese animated film The Boy and the Heron, Bale voiced a character in an English-language dub of a film by Hayao Miyazaki for the second time.[165]

Bale will next play Frankenstein's monster in Maggie Gyllenhaal's fantasy period film The Bride! It is scheduled for release in 2025.[166]

Artistry and public image

Bale is known for his exhaustive dedication to the weight fluctuations that his parts demand as well as "the intensity with which he completely inhabits his roles",[6][167] with The Washington Post's Ann Hornaday rating him among the most physically gifted actors of his generation.[168] Max O'Connell of RogerEbert.com deemed Bale's commitment to altering his physical appearance "an anchoring facet to a depiction of obsession" in his performances,[169] while the Los Angeles Times's Hugh Hart likened the urgency that drives Bale's acting style to method acting, adding that it "convincingly animates even his most extreme physical transformations."[128] Bale has said that he does not practise method acting and that he does not use a particular technique.[170] He named Rowan Atkinson as his template as an actor and added that he was mesmerised by him when they worked together.[171] He also studied the work of Gary Oldman, crediting him as the reason for his pursuit of acting.[172]

Bale has been recognised for his versatility;[40][126] Martha Ross of The Mercury News named him one of his generation's most versatile actors.[173] Known to be very private about his personal life,[9] Bale has said that his objective was to embody characters without showing any aspect of himself.[174] He explained that "letting people know who you are" does not help create different characters, viewing anonymity as "what's giving you the ability to play those characters".[18] During interviews to promote films in which he puts on an accent, Bale would continue speaking in the given accent.[175] Bale has also been noted for portraying roles with an American accent, with The Atlantic's Joe Reid listing him among those who "work least in their native accents";[176][177] in real life, Bale speaks in an "emphatic, non-posh" English accent.[15]

Bale was ranked at number eight on Forbes magazine's list of the highest-paid actors of 2014, earning $35 million.[178] He has been described as a sex symbol.[35][179]

Personal life

Bale has lived in Los Angeles since the 1990s.[15] He holds US citizenship.[147][180] Bale married Sandra "Sibi" Blažić, a former American model of Serbian descent, in Las Vegas on 29 January 2000.[175][181][182][183] They have a daughter and a son.[181] In 2000, Bale became feminist Gloria Steinem's stepson following her marriage to his father, who died in 2003 of brain lymphoma.[184][185]

Bale became a vegetarian at seven years old but in 2009 said he was "in and out of the vegetarianism now".[186] He had stopped eating red meat after reading the children's book Charlotte's Web.[175] An animal rights activist, he supports the organisations Greenpeace, the World Wide Fund for Nature, the Doris Day Animal League, the Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund International and Redwings Horse Sanctuary.[187][188] While promoting The Flowers of War in December 2011, Bale, with a crew from the television network CNN, attempted to visit Chen Guangcheng, a confined blind barefoot lawyer, in a village in eastern China. He was forced to retreat after scuffling with guards at a checkpoint.[189] Bale finally met Chen at a dinner held by the nonprofit Human Rights First the following year, during which he presented Chen with an award.[190] Bale voiced Chen's story in Amnesty International's podcast, In Their Own Words.[191] He co-founded California Together, an organisation aiming to construct a village in Palmdale, California to help siblings in foster care remain together.[192]

On 22 July 2008, Bale was arrested in London after his mother and his sister Sharon reported him to the police for an alleged assault at a hotel.[8] He was released on bail.[8] Bale denied the allegations and later called the incident "a deeply personal matter".[35] On 14 August, the Crown Prosecution Service declared they would take no further action against him because of "insufficient evidence to afford a realistic prospect of conviction".[193]

Acting credits and accolades

According to the review aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes, which assigns films scores based on the number of positive critical reviews they receive, some of Bale's highest-scoring films are The Dark Knight (2008), Ford v Ferrari (2019), American Hustle (2013), Little Women (1994), The Fighter (2010), Rescue Dawn (2007), 3:10 to Yuma (2007), The Big Short (2015), Howl's Moving Castle (2005) and The Dark Knight Rises (2012); the first, third and last of which are also listed by the data website The Numbers as his highest-grossing films, alongside Terminator Salvation (2009), Batman Begins (2005), Pocahontas (1995), Thor: Love and Thunder (2022) and Exodus: Gods and Kings (2014).[194][195]

Bale has garnered four Academy Award nominations, including two in the Best Actor category for his work in American Hustle and Vice (2018) as well as two in the Best Supporting Actor category for his work in The Fighter (2010) and The Big Short; he won one for The Fighter.[196] He has earned two Golden Globe Awards, including Best Supporting Actor – Motion Picture for his role in The Fighter and Best Actor – Motion Picture Musical or Comedy for his role in Vice, and received two nominations for Best Actor – Motion Picture Musical or Comedy for his performances in American Hustle and The Big Short and a nomination for Best Actor – Motion Picture Drama for his performance in Ford v Ferrari.[110][156] Bale has also been nominated for eight Screen Actors Guild Awards,[197] winning in the Outstanding Performance by a Male Actor in a Supporting Role category for The Fighter and the Outstanding Performance by a Cast in a Motion Picture category as part of the American Hustle cast.[198][199]

References

- ^ Ceròn, Ella (6 January 2019). "Christian Bale's Accent Is Always a Shock". The Cut. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ "Celebrity birthdays for the week of Jan. 24–30". Associated Press. 19 January 2021. Archived from the original on 20 January 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ "Christian Bale surprises the world with his British accent". Harper's Bazaar UK. 7 January 2019. Archived from the original on 19 May 2021. Retrieved 19 May 2021.

- ^ a b Francis, Damien (22 July 2008). "Batman star Christian Bale arrested". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ^ Butler, Tom (3 June 2019). "Christian Bale's accent is seriously confusing people in the first 'Le Mans '66' trailer". Yahoo! Movies. Archived from the original on 5 December 2020. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- ^ a b Hiscock, John (21 January 2011). "Christian Bale: Yes, it is the same guy". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 23 January 2011. Retrieved 9 February 2014.

- ^ a b Fisher, Luchina (27 July 2008). "Big Tent Childhood: Growing up in the Circus". ABC News. Archived from the original on 27 October 2020. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- ^ a b c Irvine, Chris; Edwards, Richard (22 July 2008). "Batman actor Christian Bale released after assault allegation arrest". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 9 September 2019. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ a b Heaf, Jonathan (23 July 2012). "Christian Bale on suffering from insomnia and running into Viggo Mortensen in Rome". British GQ. Archived from the original on 23 September 2016. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ Black, Johnny (6 December 2013). "Christian Bale: 20 Things You (Probably) Don't Know About the 'Out of the Furnace' Star". Moviefone. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ^ "Dorset celebrities". BBC News. 24 September 2014. Archived from the original on 16 April 2021. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Riley, Jenelle (26 November 2013). "Christian Bale: Reluctant Movie Star Talks 'Furnace', 'Hustle'". Variety. Archived from the original on 31 July 2020. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- ^ Blunden, Mark (13 April 2012). "Christian Bale's sister says actor needs help to deal with temper". Evening Standard. Archived from the original on 8 June 2021. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ^ Burns, Judith (3 June 2017). "Sporting plan to boost boys in ballet". BBC News. Archived from the original on 21 January 2019. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g Carroll, Rory (5 January 2018). "Christian Bale: 'I was asked to do a romantic comedy. I thought they'd lost their minds'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ Gerardi, Matt (8 September 2016). "A brief history of video game cereals and their ridiculous commercials". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on 9 February 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ Yarrow, Andrew L. (16 December 1987). "Boy In 'Empire' Calls Acting 'Really Good Fun'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 23 July 2020. Retrieved 1 May 2021.

- ^ a b Feinberg, Scott (7 December 2013). "'Out of the Furnace' Star Christian Bale on His 'Love-Hate' Relationship with Acting (Q&A)". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 18 May 2021. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- ^ Lewis, Andy; Anderman, Maya (6 May 2016). "Discovered by Spielberg: How a Lucky Encounter With the Director Launched These 6 Stars". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 8 June 2021. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ^ Kappes, Serena (20 October 2004). "5 Things You Gotta Know About Christian Bale". People. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ Sanello, Frank (20 December 1987). "Christian Bale: Spielberg's Newest Child Star". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 23 July 2021. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- ^ a b Child, Ben (9 December 2013). "Christian Bale: pressure as a child formed 'love/hate' relationship with acting". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 9 October 2015. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Christian Bale". BBC Cymru Wales. Archived from the original on 13 February 2009. Retrieved 13 April 2009.

- ^ Clute, John; Grant, John (1997). The Encyclopedia of Fantasy. London: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 558. ISBN 978-0312158972.

- ^ Hedberg, Mats (16 October 1987). "Fler premiärer". Svenska Dagbladet (in Swedish). p. 50 (4:2). Archived from the original on 16 August 2021. Retrieved 16 August 2021.

- ^ Singh, Anita (22 July 2008). "Christian Bale – profile". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 16 February 2018. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ Willman, Chris (22 January 1990). "TV Review : Hestons Sail for 'Treasure Island'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 30 April 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ Jensen, Jeff (17 July 2012). "The Dark Knight Rises...but not for Broadway musicals: Why Christian Bale won't be seeing 'Newsies'". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ Milzoff, Rebecca (29 February 2012). "How Does Newsies Hold Up?". Vulture. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 17 June 2021.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (5 March 1993). "Review/Film; Jazz in Nazi Germany: Youthful Resistance". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ a b Spencer, Ashley (12 September 2019). "'Little Women': An Oral History of the 1994 Adaptation". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 8 February 2021. Retrieved 17 June 2021.

- ^ Allen, Kelly; Miller, Gregory E. (20 August 2020). "40 Actors You Completely Forgot Voiced Disney Characters". Cosmopolitan. Archived from the original on 3 September 2020. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ Horn, John (30 June 1995). "'Batman Forever' Bloodies 'Pocahontas'". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 24 May 2015. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Grierson, Tim; Leitch, Will (20 April 2020). "The Best Christian Bale Movies, Ranked". Vulture. Archived from the original on 30 January 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ a b c "'Knight's' Bale: Who is that masked man?". CNN. 28 July 2008. Archived from the original on 25 March 2021. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ Stack, Peter (14 May 1999). "'Dream' Interpretation / Stellar cast adds comic madness to lush, over-the-top 'Midsummer'". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on 24 October 2020. Retrieved 1 May 2021.

- ^ Gopalan, Nisha (23 March 2000). "American Psycho: the story behind the film". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- ^ Mazziotta, Julie (22 January 2020). "Christian Bale 'Had Never Gone to a Gym' Before American Psycho". People. Archived from the original on 23 January 2020. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ Fischer, Paul (14 April 2000). "Unmasking an American Psycho". Dark Horizons. Archived from the original on 2 February 2018. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ a b "The method in my madness". The Guardian. 6 April 2000. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- ^ Kaufman, Anthony (14 April 2000). "Interview: 9-Months Pregnant and Delivering "American Psycho," Director Mary Harron". IndieWire. Archived from the original on 12 October 2008. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (14 April 2000). "American Psycho". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on 20 January 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ Sharf, Zack (14 April 2020). "Mary Harron Reflects on Nearly Losing 'American Psycho' Director Gig for Rejecting DiCaprio". IndieWire. Archived from the original on 11 March 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ Garner, Dwight (24 March 2016). "In Hindsight, an 'American Psycho' Looks a Lot Like Us". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 1 May 2021.

- ^ Desta, Yohana (5 October 2018). "Eight Times Christian Bale Totally Transformed for a Movie Role". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ Dilard, Clayton (3 December 2013). "Box Office Rap: Out of the Furnace and Christian Bale's Body (of Work)". Slant Magazine. Archived from the original on 28 October 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- ^ Fuller, Graham (17 July 2012). "New Again: Christian Bale". Interview. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 17 June 2021.

- ^ Schwarzbaum, Lisa (14 March 2003). "Laurel Canyon". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 29 October 2020. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- ^ Cawthorne, Alec. "Christian Bale interview: Reign Of Fire (2002)". BBC Cymru Wales. Archived from the original on 27 December 2020. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- ^ Chavel, Sean. "Interview with Christian Bale of Reign of Fire". UGO Networks. Archived from the original on 10 April 2005. Retrieved 8 June 2006.

- ^ Francisco, Eric (1 June 2020). "The one sci-fi movie you need to watch before it leaves Netflix this week". Inverse. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 1 May 2021.

- ^ Lincoln, Kevin (12 October 2016). "The Gun-Fu of John Wick and John Woo: A Primer". Vulture. Archived from the original on 13 October 2016. Retrieved 1 May 2021.

- ^ Otto, Jeff (15 June 2005). "Interview: Christian Bale". IGN. Archived from the original on 30 June 2017. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- ^ a b Applebaum, Stephen (25 February 2005). "Christian Bale: Cinema's extremist". The Independent. Archived from the original on 30 January 2021. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- ^ Nash, Brad (14 May 2020). "The Story Of Christian Bale's The Machinist Transformation Is Insane". GQ Australia. Archived from the original on 18 January 2021. Retrieved 1 May 2021.

- ^ Schwarzbaum, Lisa (21 January 2014). "The Thin Men: Actors who starve themselves for an Oscar". BBC. Archived from the original on 12 June 2021. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- ^ a b Rosen, Lisa (21 October 2004). "Losing himself in the role". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 1 May 2021. Retrieved 1 May 2021.

- ^ McClelland, Nicholas Hegel (2 July 2012). "The Evolution of Christian Bale". Time. Archived from the original on 27 December 2019. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- ^ Topel, Fred (15 October 2004). "Christian Bale talks The Machinist". MovieWeb. Archived from the original on 22 July 2010. Retrieved 5 May 2008.

- ^ Applebaum, Stephen. "Christian Bale interview: The Machinist (2004)". BBC Cymru Wales. Archived from the original on 27 December 2020. Retrieved 20 April 2009.

- ^ Moore, Roger (10 December 2004). "Bale Chills to the Bone". Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on 1 December 2020. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- ^ McCarthy, Todd (29 January 2004). "The Machinist". Variety. Archived from the original on 16 May 2021. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- ^ Greenberg, James (8 May 2005). "Rescuing Batman". Los Angeles Times. p. E-10. Archived from the original on 2 December 2008. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- ^ "Actor Bale lands Batman role". BBC News. 12 September 2003. Archived from the original on 30 November 2008. Retrieved 9 July 2021.

- ^ Dibin, Emma (14 April 2016). "Why Christian Bale-Style Yo-Yo Dieting Is Terrible For You". Esquire. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 1 May 2021.

- ^ Evans, Matthew (11 February 2017). "Christian Bale's 5 Craziest Body Transformations". Men's Health. Archived from the original on 24 January 2021. Retrieved 1 May 2021.

- ^ Maher, John (16 July 2018). "Christian Bale's infamous Dark Knight voice was the only option". Polygon. Archived from the original on 2 January 2021. Retrieved 28 May 2021.

- ^ Dargis, Manohla (15 June 2005). "Dark Was the Young Knight Battling His Inner Demons". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 29 May 2015. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ "Gay cowboys the best kissers". The Sydney Morning Herald. 4 June 2006. Archived from the original on 6 June 2009. Retrieved 13 April 2009.

- ^ Forbes, Jake (5 June 2005). "'Howl's' a natural draw for an anime master". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 30 April 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ Winning, Joshua (7 August 2012). "Worst To Best: Christian Bale". Total Film. Archived from the original on 13 August 2021. Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- ^ "Blanchett joins Toronto festival lineup". USA Today. 26 July 2005. Archived from the original on 30 June 2012. Retrieved 13 April 2009.

- ^ Dargis, Manohla (20 January 2006). "A Briefer Account of Jamestown's Founding". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ "Herzog hails Bale". Irish Examiner. 24 March 2006. Archived from the original on 1 May 2021. Retrieved 1 May 2021.

- ^ Baumgarten, Marjorie (27 July 2007). "Rescue Dawn – Movie Review". The Austin Chronicle. Archived from the original on 3 March 2021. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- ^ Jolin, Dan (17 August 2020). "The Prestige: Inside Christopher Nolan's Movie Magic Trick". Empire. Archived from the original on 2 February 2021. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- ^ Carle, Chris (12 October 2006). "Casting The Prestige". IGN. Archived from the original on 2 December 2020. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- ^ Child, Ben (28 November 2014). "Prestige novelist: Christopher Nolan's Batman movies 'boring and pretentious'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- ^ Sims, David (4 August 2020). "'Inception' at 10: Christopher Nolan Is Still Saving Cinema". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 27 February 2021. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- ^ Mendelson, Scott (1 November 2020). "Box Office: 'Tenet' Tops Chris Nolan's Best Movie, 'After We Collided' Plunges 76%". Forbes. Archived from the original on 12 June 2021. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- ^ Scott, A. O. (20 October 2006). "Two Rival Magicians, and Each Wants the Other to Go Poof". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 28 May 2021.

- ^ Hill, Logan (24 August 2007). "The Great Obsessive". New York. Archived from the original on 10 April 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ "3:10 to Yuma: Christian Bale vs. Russell Crowe". ComingSoon.net. 3 September 2007. Archived from the original on 5 March 2009. Retrieved 26 February 2010.

- ^ Stolworthy, Jacob (12 March 2021). "The Dark Knight almost featured a scene that would have changed the entire movie". The Independent. Archived from the original on 12 March 2021. Retrieved 1 May 2021.

- ^ Sharf, Zack (18 July 2018). "'The Dark Knight' Returning to IMAX Theaters". IndieWire. Archived from the original on 19 July 2018. Retrieved 1 May 2021.

- ^ Celizic, Mike (14 July 2008). "Christian Bale: Ledger had 'wonderful time' as Joker". Today. Archived from the original on 23 November 2020. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- ^ Tapley, Kristopher (17 July 2018). "'Dark Knight' Changed Movies, and the Oscars, Forever". Variety. Archived from the original on 24 April 2021. Retrieved 19 May 2021.

- ^ Dockterman, Eliana (30 August 2018). "35 Sequels That Are Better Than the Original Movie". Time. Archived from the original on 29 January 2021. Retrieved 19 May 2021.

- ^ "New "Terminator" film set for May 2009 release". Reuters. 6 February 2008. Archived from the original on 30 April 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ Anthony, Andrew (16 May 2009). "Christian Bale: The Terminator with a temper". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 19 May 2021.

- ^ a b "Whoopi Goldberg defends Christian Bale". Today. 3 February 2009. Archived from the original on 7 January 2018. Retrieved 6 February 2009.

- ^ Adams, Guy (4 February 2009). "Bale turns American psycho with expletive-laden tantrum on set". The Independent. Archived from the original on 5 February 2009. Retrieved 4 February 2009.

- ^ "Wrestler director supports Bale". BBC News. 5 February 2009. Archived from the original on 16 February 2009. Retrieved 6 February 2009.

- ^ Romano, Nick (25 March 2021). "Sharon Stone defends Christian Bale's famous Terminator outburst". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 26 March 2021. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- ^ Duke, Alan (6 February 2009). "Bale apologizes for 'Terminator' tantrum". CNN. Archived from the original on 28 January 2020. Retrieved 13 April 2009.

- ^ "Actor Bale speaks out over rant". BBC News. 6 February 2009. Archived from the original on 21 October 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2009.

- ^ Scott, A. O. (20 May 2009). "A Crude, Imperfect Enemy, Bolts and All, in McG's Film". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ a b Child, Ben (3 December 2014). "Christian Bale: I won't be back to work with McG". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 30 January 2021. Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- ^ Puig, Claudia (20 May 2009). "There's little to salvage from this 'Terminator'". USA Today. Archived from the original on 15 October 2020. Retrieved 28 May 2021.

- ^ Wilson, Jake (4 June 2009). "Headed for termination not salvation". The Age. Archived from the original on 4 November 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2021.

- ^ Sharf, Zack (9 January 2018). "Christian Bale Never Wanted to Star in 'Terminator Salvation' and Said No Three Times: 'It's a Great Thorn in My Side'". IndieWire. Archived from the original on 28 February 2021. Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- ^ Jurgensen, John (16 July 2009). "Christian Bale and Michael Mann on John Dillinger, Gangsters, and 'Public Enemies'". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 30 April 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ Donahue, Ann (18 July 2009). "Q&A: "Enemies" composer gives voice to "inner snarling"". Reuters. Archived from the original on 18 May 2021. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- ^ Stolworthy, Jacob (23 August 2016). "Michael Mann toned down Public Enemies scene because the real-life events were so unbelievable". The Independent. Archived from the original on 5 June 2021. Retrieved 19 May 2021.

- ^ Zak, Dan (1 July 2009). "Movie Review: 'Public Enemies' With Johnny Depp". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 24 September 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- ^ Orr, Christopher (2 July 2009). "The Movie Review: 'Public Enemies'". The New Republic. Archived from the original on 27 February 2021. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- ^ Riley, Jenelle (25 November 2010). "The great 'Contender' – Christian Bale cracks wise". Reuters. Archived from the original on 1 May 2021. Retrieved 1 May 2021.

- ^ LaSalle, Mick (17 December 2010). "'The Fighter' review: Actors pack a punch". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on 26 September 2020.

- ^ "Christian Bale wins Oscar for "The Fighter"". Reuters. 28 February 2011. Archived from the original on 7 August 2020. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- ^ a b c Kay, Jeremy (7 January 2019). "Christian Bale thanks 'Satan' in Golden Globes speech". Screen Daily. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ a b "The story behind Chinese war epic The Flowers of War". BBC News. 24 January 2012. Archived from the original on 12 February 2018. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ^ von Tunzelmann, Alex (2 August 2012). "The Flowers of War fails to bloom for Chinese film industry". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 23 November 2018. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ^ Mitchell, Robert (20 July 2012). "Biz, nation reel from Colorado shooting". Variety. Archived from the original on 23 September 2016. Retrieved 1 May 2021.

- ^ Hiscock, John (18 July 2012). "Christian Bale interview: The Dark Knight Rises". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 27 April 2020. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- ^ Lee, Kurtis; Parker, Ryan (24 July 2012). "Batman actor Christian Bale visits victims, hospital personnel". The Denver Post. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ^ Finke, Nikki (3 September 2012). "'The Dark Knight Rises' Becomes 11th Film in History To Pass $1 Billion Milestone". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 1 May 2021.

- ^ Ryan, Joal (24 January 2020). "Biggest movie franchises: Marvel, Star Wars, Harry Potter and more ranked by box office". CBS News. Archived from the original on 12 June 2021. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- ^ Eames, Tom (23 August 2017). "The highest-grossing film franchises – the 50 biggest film series ever". Digital Spy. Archived from the original on 12 June 2021. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- ^ Sharf, Zack (18 November 2019). "Christian Bale Turned Down Request for Fourth Batman Movie Because of Nolan's Wish". IndieWire. Archived from the original on 27 November 2020. Retrieved 1 May 2021.

- ^ "Christian Bale keen for Star Wars role". Associated Press. 5 January 2018. Archived from the original on 30 April 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^

- Child, Ben (4 March 2016). "Why Christian Bale will always be the best Batman". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 5 February 2021. Retrieved 1 May 2021.

- Rawat, Kshitij (7 March 2022). "After The Batman, a ranking of every live-action Bruce Wayne: Who's the best among Ben Affleck, Christian Bale, Robert Pattinson?". The Indian Express. Archived from the original on 7 August 2022. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- Naidoo, Neville (7 August 2023). "10 Reasons Why Christian Bale Will Always be The Greatest Batman Ever". MovieWeb. Archived from the original on 7 August 2023. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- Bradshaw, Paul (17 March 2021). "Every actor who's played Batman – ranked from worst to best". NME. Archived from the original on 17 March 2021. Retrieved 1 May 2021.

- "Christian Bale voted the best Batman ever by fans". Radio Times. Archived from the original on 1 May 2021. Retrieved 1 May 2021.

- ^ Stolworthy, Jacob (4 March 2016). "Christian Bale doesn't rate his Batman performance in the Dark Knight trilogy". The Independent. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- ^ Dargis, Manohla (3 December 2013). "'Out of the Furnace,' With Christian Bale". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 11 December 2020. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- ^ Lang, Brent (11 November 2013). "'Out of the Furnace' Reviews: Do Critics Think It's Another 'Deer Hunter'?". TheWrap. Archived from the original on 23 August 2014. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- ^ Labrecque, Jeff (6 December 2013). "'Out of the Furnace': The reviews are in..." Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- ^ a b Tapley, Kristopher (31 August 2017). "Top 10 Christian Bale Performances". Variety. Archived from the original on 22 February 2021. Retrieved 1 May 2021.

- ^ Reid, Joe (13 December 2013). "'American Hustle' Can't Close the Deal". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 18 January 2021. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- ^ a b c Hart, Hugh (29 January 2019). "Christian Bale: Man of a thousand physiques". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ Rosen, Christopher (20 December 2013). "Christian Bale's 'American Hustle' Transformation Even Fooled Co-Star". HuffPost. Archived from the original on 20 January 2021. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- ^ Bernstein, Paula (11 December 2013). "10 New Things We Learned About 'American Hustle:' De Niro Didn't Recognize Christian Bale, Why Bradley Cooper Curled His Hair & More". IndieWire. Archived from the original on 18 January 2021. Retrieved 19 May 2021.

- ^ Neumaier, Joe (12 December 2013). "'American Hustle': Movie review". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on 17 December 2020. Retrieved 19 May 2021.

- ^ Merry, Stephanie (27 February 2014). "Why 'American Hustle' should win the Best Picture Oscar". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 18 January 2021. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- ^ Child, Ben (9 December 2014). "Christian Bale defends Ridley Scott over Exodus 'whitewashing'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 27 February 2021. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- ^ Faughdner, Ryan (12 December 2014). "'Exodus: Gods and Kings' rides in with $1.2 million Thursday night". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 31 July 2020. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- ^ Williams, Joe (11 December 2014). "Thou shalt not waste time on 'Exodus: Gods and Kings'". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- ^ Sims, David (3 March 2016). "Movie Review: 'Knight of Cups,' with Christian Bale, Cate Blanchett, and Natalie Portman, Is Terrence Malick's Version of Hollywood Satire". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 26 October 2020. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- ^ Child, Ben (9 February 2021). "Christian Bale baffled by Terrence Malick on Knight of Cups shoot". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2 December 2020. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- ^ Barker, Andrew (13 November 2015). "Film Review: 'The Big Short'". Variety. Archived from the original on 29 January 2016. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- ^ Morgenstern, Joe (10 December 2015). "'The Big Short' Review: The Comic Beauties of a Bubble". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 27 January 2016. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- ^ King, Susan (28 February 2016). "'The Big Short' wins the Oscar for adapted screenplay". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 1 July 2017. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- ^ Lang, Brent (10 December 2015). "'Carol,' Netflix Lead Golden Globes Nomination". Variety. Archived from the original on 11 December 2015. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- ^ D'Alessandro, Anthony (29 March 2018). "'King Arthur', 'Great Wall', 'Geostorm' & More: Box Office Bombs Of 2017". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on 12 February 2021. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- ^ Catsoulis, Jeannette (20 April 2017). "Review: 'The Promise' Finds a Love Triangle in Constantinople". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- ^ a b Morgan, David (18 December 2017). "Christian Bale on western "Hostiles," and gaining weight to play Dick Cheney". CBS News. Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- ^ Jolin, Dan (4 September 2017). "Hostiles Review". Empire. Archived from the original on 17 December 2019. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- ^ Fear, David (2 December 2018). "'Mowgli' Review: Welcome to the Jungle (Book)". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 4 December 2018. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- ^ a b "Christian Bale: Donald Trump is a 'clown' who doesn't understand government". The Scotsman. 24 January 2019. Archived from the original on 3 November 2020. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ Smith, David (20 December 2018). "Dick Cheney is back but rehabilitation is not on Darth Vader's agenda". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- ^ Miller, Julie (2 October 2018). "See Christian Bale's Incredible Dick Cheney Transformation in First Vice Photo". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on 29 December 2020. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- ^ Schaffstall, Katherine (17 December 2018). "'Vice' Reviews: Critics on Dick Cheney Film Starring Christian Bale". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 18 May 2021. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- ^ Phillips, Kristine (8 January 2019). "Christian Bale thanked Satan for his portrayal of Dick Cheney. The Church of Satan approves". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 10 November 2020. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- ^ Kurtz, Judy (22 January 2019). "Christian Bale gets Oscar nomination for Cheney portrayal". The Hill. Archived from the original on 30 June 2019. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ Samuels, Brett (9 January 2019). "Liz Cheney on Christian Bale: He had chance to play 'a real superhero' and 'screwed it up'". The Hill. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- ^ a b Desta, Yohana (11 November 2019). "Christian Bale Swears He's Done Gaining and Losing Weight for Roles". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on 29 October 2020. Retrieved 1 May 2021.

- ^ Kelly, Mary Louise (14 November 2019). "Matt Damon On Playing A Race Car Driver in Famous Ford-Ferrari Rivalry Of The '60s". NPR. Archived from the original on 20 December 2019. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ a b D'Alessandro, Anthony (6 January 2020). "'Dark Knight' Star Christian Bale in Talks For Marvel's 'Thor: Love And Thunder'". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ Ettenhofer, Valerie (27 June 2022). "Christian Bale Reveals A Terrifying Cut Scene From Thor: Love And Thunder". /Film. Archived from the original on 27 June 2022. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- ^ Ortiz, Andi (5 July 2022). "'Thor: Love and Thunder' Reviews: Critics Enjoy Taika Waititi's 'Surface Pleasures,' But Question Its Place in the MCU". TheWrap. Archived from the original on 9 July 2022. Retrieved 10 July 2022.

- ^ a b Chuba, Kirsten (7 January 2023). "Christian Bale on Taking Producer Credits on Amsterdam, Pale Blue Eye". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 7 January 2023. Retrieved 11 January 2023.

- ^ Ryan, Patrick (27 April 2022). "Taylor Swift brings the waterworks with Chris Rock in 'Amsterdam' film". USA Today. Archived from the original on 28 April 2022. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ Wiseman, Andreas (6 March 2021). "Netflix Strikes EFM Record $55M Worldwide Deal For Christian Bale Cross Creek Thriller 'The Pale Blue Eye'". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on 7 March 2021. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- ^ McClintock, Pamela (11 October 2022). "'Amsterdam' Box Office: Movie to Lose $80M-$100M". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 11 October 2022. Retrieved 21 November 2022.

- ^ Rubin, Rebecca (24 October 2022). "Black Adam, Ticket to Paradise Benefit From Star Power at Box Office". Variety. Archived from the original on 24 October 2022. Retrieved 21 November 2022.

- ^ Hayes, Patrick (11 January 2023). "Why The Pale Blue Eye Has Been Greeted with Such Critical Negativity". MovieWeb. Archived from the original on 21 January 2023. Retrieved 28 April 2023.

- ^ Taylor, Drew (17 October 2023). "Hayao Miyazaki's 'The Boy and the Heron' English Voice Cast Includes Christian Bale, Robert Pattinson". TheWrap. Archived from the original on 17 October 2023. Retrieved 17 October 2023.

- ^ Sharf, Zack (4 April 2024). "Christian Bale Transforms Into Frankenstein's Monster in First Look at Maggie Gyllenhaal's 'The Bride'". Variety. Archived from the original on 15 June 2024. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ Lattanzio, Ryan (9 November 2019). "Christian Bale Says He's Done Getting Fat for Roles". IndieWire. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ Hornaday, Ann (13 July 2007). "'Rescue Dawn': A Light in War's Densest Jungle". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 27 September 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- ^ O'Connell, Max (14 January 2019). "Obsession and The Void: The Performances of Christian Bale". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on 4 December 2020. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ "Christian Bale 'wings it' on set". Associated Press. 28 December 2018. Archived from the original on 29 April 2021. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ McGurk, Stuart (1 October 2019). "Matt Damon and Christian Bale interview: When Bourne met Batman". British GQ. Archived from the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved 19 May 2021.

- ^ Mathew, Suresh (26 November 2018). "Christian Bale Says He's Almost Done With Physical Transformations". The Quint. Archived from the original on 30 November 2018. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- ^ Ross, Martha (13 April 2017). "Christian Bale goes from 'American Psycho' to Dick Cheney with new role". The Mercury News. Archived from the original on 3 December 2018. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ^ Marchese, David (12 December 2014). "Christian Bale Is Our Least Relatable Movie Star". Vulture. Archived from the original on 4 December 2020. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ a b c Hilton, Beth (2 July 2008). "Ten Things You Never Knew About Christian Bale". Digital Spy. Archived from the original on 3 June 2020. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- ^ Stolworthy, Jacob (14 November 2019). "Christian Bale's accent confuses British television viewers: 'It's weird hearing him speak in his real voice'". The Independent. Archived from the original on 14 November 2019. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ Reid, Joe (6 December 2013). "Christian Bale and the Actors Who Work Least in Their Native Accents". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 15 August 2020. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ Child, Ben (22 July 2014). "Robert Downey Jr tops list of highest paid actors for second year running". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 May 2021. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ Robinson, Tasha (16 October 2007). "A filmgoer's guide to bad sex with Christian Bale". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on 3 July 2020. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ "Christian Bale: The Full Shoot And Interview". Esquire. 10 December 2014. Archived from the original on 8 January 2019. Retrieved 17 February 2018.

- ^ a b Russian, Ale (30 January 2019). "Christian Bale and Wife Enjoy Bike Ride on 19th Wedding Anniversary – Day Before His Birthday!". People. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ Mitchell, Amanda (17 January 2019). "Who Is Christian Bale's Wife Sibi Blazic? The Model Changed Everything for the Actor". Marie Claire. Archived from the original on 6 February 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ Stets, Regina (17 July 2021). "Sibi Blažić's biography: what is known about Christian Bale's wife?". Legit.ng - Nigeria news. Retrieved 19 October 2024.

- ^ von Zeilbauer, Paul (1 January 2004). "David Bale, 62, Activist and businessman". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 11 November 2014. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- ^ Denes, Melissa (16 January 2005). "'Feminism? It's hardly begun'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ^ Corsello, Andrew (1 May 2009). "A Nice Quiet Chat with Christian Bale". GQ. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ Jan, Stuart (13 April 2000). "Bale's 'Psycho' Analysis". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 30 April 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ Walsh, Nick Paton (20 June 1999). "Christian Bale". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 1 October 2019. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ Jiang, Steven (17 December 2011). "'Batman' star Bale punched, stopped from visiting blind Chinese activist". CNN. Archived from the original on 16 December 2011. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- ^ "Chen Guangcheng Honored by Human Rights First, Meets Bale". The Wall Street Journal. 25 October 2012. Archived from the original on 8 July 2021. Retrieved 9 July 2021.

- ^ Sturges, Fiona (3 February 2016). "In Their Own Words, podcast review: Christian Bale is outshone by a human rights champion". The Independent. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 9 July 2021.

- ^ Gardner, Chris (8 February 2024). "Christian Bale Breaks Ground on 16-Year Passion Project: Homes for Foster Siblings". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 9 February 2024. Retrieved 10 February 2024.

- ^ "No assault charge for Batman Bale". BBC News. 14 August 2008. Archived from the original on 27 December 2020. Retrieved 6 February 2009.

- ^ "All Christian Bale Movies Ranked". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on 6 February 2021. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

- ^ "Christian Bale – Box Office". The Numbers. Archived from the original on 10 July 2022. Retrieved 10 July 2022.

- ^ Roeper, Richard (11 November 2019). "Christian Bale says his 'Ford v Ferrari' ride beats the Batmobile". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on 11 November 2019. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ Turan, Kenneth (16 January 2020). "Performances we love: Christian Bale fools us again". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 20 January 2021. Retrieved 10 September 2021.

- ^ Kit, Borys; Powers, Lindsay (30 January 2011). "SAG Awards 2011: Christian Bale Surprised On Stage by Dicky Eklund". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 10 September 2021. Retrieved 10 September 2021.

- ^ "American Hustle cast tops SAG awards". BBC News. 19 January 2014. Archived from the original on 10 September 2021. Retrieved 10 September 2021.

Further reading

- Holmstrom, John (1996). The Moving Picture Boy: An International Encyclopaedia from 1895 to 1995. Norwich: Michael Russell. p. 394. ISBN 978-0859551786.

External links

- Christian Bale at IMDb

- Christian Bale at AllMovie

- Christian Bale collected news and commentary at The New York Times

- 1974 births

- Living people

- 20th-century English male actors

- 21st-century American male actors

- 21st-century English male actors

- Actors from Haverfordwest

- American male film actors

- American male video game actors

- American male voice actors

- Best Musical or Comedy Actor Golden Globe (film) winners

- Best Supporting Actor Academy Award winners

- Best Supporting Actor Golden Globe (film) winners

- English emigrants to the United States

- English expatriates in Portugal

- English film producers

- English male child actors

- English male film actors

- English male video game actors

- English male voice actors

- Film producers from Los Angeles

- Male actors from Bournemouth

- Male actors from Los Angeles

- Male actors from Pembrokeshire

- Male actors from Surrey

- Naturalized citizens of the United States

- Outstanding Performance by a Cast in a Motion Picture Screen Actors Guild Award winners

- Outstanding Performance by a Male Actor in a Supporting Role Screen Actors Guild Award winners

- People educated at Bournemouth School