Sheep farming

Sheep farming or sheep husbandry is the raising and breeding of domestic sheep. It is a branch of animal husbandry. Sheep are raised principally for their meat (lamb and mutton), milk (sheep's milk), and fiber (wool). They also yield sheepskin and parchment.

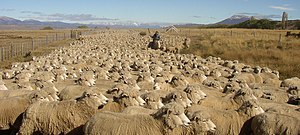

Sheep can be raised in a range of temperate climates, including arid zones near the equator and other torrid zones. Farmers build fences, housing, shearing sheds, and other facilities on their property, such as for water, feed, transport, and pest control. Most farms are managed so sheep can graze pastures, sometimes under the control of a shepherd or sheep dog.

Farmers can select from various breeds suitable for their region and market conditions. When the farmer sees that a ewe (female adult) is showing signs of heat or estrus, they can organise for mating with males. Newborn lambs are typically subjected to lamb marking, which involves tail docking, mulesing, earmarking, and males may be castrated.[1]

Sheep production worldwide

[edit]

According to the FAOSTAT database of the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, the top five countries by number of head of sheep (average from 1993 to 2013) were: mainland China (146.5 million head), Australia (101.1 million), India (62.1 million), Iran (51.7 million), and the former Sudan (46.2 million).[2] Approximately 540 million sheep are slaughtered each year for meat worldwide.[3]

In 2013, the five countries with the largest number of head of sheep were mainland China (175 million), Australia (75.5 million), India (53.8 million), the former Sudan (52.5 million), and Iran (50.2 million). In 2018, Mongolia had 30.2 million sheep. In 2013, the number of head of sheep were distributed as follows: 44% in Asia, 28.2% in Africa; 11.2% in Europe, 9.1% in Oceania, 7.4% in the Americas.

The top producers of sheep meat (average from 1993 to 2013) were as follows: mainland China (1.6 million); Australia (618,000), New Zealand (519,000), the United Kingdom (335,000), and Turkey (288,857).[2] The top five producers of sheep meat in 2013 were mainland China (2 million), Australia (660,000), New Zealand (450,000), the former Sudan (325,000), and Turkey (295,000).[2]

U.S. sheep production

[edit]In the United States, inventory data on sheep began in 1867, when 45 million head of sheep were counted in the United States.[4] The numbers of sheep peaked in 1884 at 51 million head, and then declined over time to almost 6 million head.[4]

Between the 1960s and 2012, per capita per year consumption of lamb and mutton has declined from nearly five pounds (about 2 kg) to just about one pound (450g), because of competition from poultry, pork, beef, and other meats.[4] Between the 1990s and 2012, U.S. sheep operations declined from around 105,000 to around 80,000 because of shrinking revenues and low rates of return.[4] According to the Economic Research Service of the United States Department of Agriculture, the sheep industry accounts for less than one percent of U.S. livestock industry receipts.[4]

Reproduction

[edit]Lambing

[edit]

Most lambs are born outdoors. Ewes can be made to give birth in fall, winter, or spring months, either by artificial insemination or by facilitating natural mating.[5] Fall lambing is generally not done as the lamb crop percentage is likely to be low; ewes often need hormone therapy to induce estrus and ovulation, and farm labor is often busy elsewhere during fall lambing. Furthermore, fall-born lambs can be weak and small because of heat stress during the summer gestation period. Spring lambing has the advantage of coinciding with the natural breeding and lambing seasons, but supplemental feed is often needed. The advantage of winter lambing is that the lambs are weaned in spring when pastures are most fertile. This allows the lambs to grow more quickly, and to be sold for slaughter during the summer (when prices are generally high), but it results in roughly one in every four newborn lambs dying within a few days of birth of malnutrition, disease, or exposure to the harsh cold. In the UK, it results in around 4 million newborn lamb deaths.[6] "Accelerated lambing" is the practice of lambing more than once a year, typically every 6 to 8 months. The advantages of accelerated lambing include increased lamb production, having lambs available for slaughter at different seasons, year-round use of labor and facilities, and increased income per ewe. It requires intensive management, early weaning, exogenous hormones, and artificial impregnation. It is often used to make old or soon-to-be infertile ewes give birth one more time before they are slaughtered.[5]

Lamb marking

[edit]

After lambs are several weeks old, lamb marking is carried out.[7] This involves ear tagging, docking, mulesing, and castrating.

Ear tags with numbers are attached, or ear marks are applied, for ease of later identification of sheep.

Tail docking is commonly done for welfare, having been shown to reduce risk of flystrike when compared to the alternative of letting sheep collect waste around their buttocks.[8]

The Merino breed, accounting for around 80% of the wool produced in Australia, have been selectively bred to have wrinkled skin resulting in excessive amounts of wool while making them much more prone to flystrike.[9][10][11] To reduce the risk of flystrike caused by soiling for the lambs who make it to summer, Merino lambs are often mulesed at the same time, which involves cutting off the skin around their buttocks and the base of their tail with metal shears. If the lambs are younger than 6 months, it is legal to do this in Australia without any pain relief.[12]

Male lambs are typically castrated. Castration is performed on ram lambs not intended for breeding, although some shepherds choose to omit this for ethical, economic or practical reasons.[7] A common castration technique is "elastration", which involves a thick rubber band being placed around the base of the infant's scrotum, obstructing the blood supply and causing atrophy. This method causes severe pain to the lambs who are provided no pain relief during the process.[13] Elastration is also commonly used for docking.

Based on the preference of the shepherd, docking and castration are commonly done after 24 hours (to avoid interference with maternal bonding and consumption of colostrum) and are often done not later than one week after birth to minimize pain, stress, recovery time, and complications.[14][15] Ram lambs that will either be slaughtered or separated from ewes before sexual maturity are not usually castrated.[16] Objections to all these procedures have been raised by animal rights groups, but farmers defend them by saying they reduce costs, and inflict only temporary pain.[17][7]

Healthcare

[edit]Nutrition

[edit]Although sheep primarily consume pasture roughage, they are sometimes given supplemental feed, such as corn and hay provided by the shepherds from their own fields.

Shearing

[edit]Sheep not meant to be eaten are typically shorn annually in a shearing shed. Ewes tend to be shorn immediately prior to lambing.[18] Shearing can be done with either manual blades or machine shears. In Australia, sheep shearers are paid by the number of sheep shorn, not by the hour, and there are no requirements for formal training or accreditation.[19] Because of this, it is alleged that speed is prioritised over precision and care of the animal.[20]

Crutching

[edit]Crutching is the practice of removing wool for hygiene reasons, typically from around the face and buttocks.

Saleyards

[edit]Sheep sold for slaughter often pass through saleyards, also known as auctions.

Slaughter

[edit]

When sheep can no longer produce enough wool to be considered profitable, they are sent to slaughter and sold as mutton, and lambs raised for meat are killed between 4 and 12 months of age.[21] Sheep have a natural lifespan of 12–14 years.

Herding

[edit]Breeds

[edit]Environmental impact

[edit]George Monbiot's 2013 book Feral[22] attacks sheep farming in the United Kingdom as "a slow-burning ecological disaster, which has done more damage to the living systems of this country than either climate change or industrial pollution. Yet scarcely anyone seems to have noticed."[23] He particularly looks at sheep farming in Wales.

See also

[edit]- Dolly (sheep)

- Glossary of sheep husbandry

- Guard llama

- History of the domestic sheep

- Jacob

- Livestock guardian dog

- Patagonian sheep farming boom

- Sheep station, a large property for raising of sheep in Australia or New Zealand

- Transhumance

References

[edit]- ^ A Beginner's Guide to Raising Sheep.

- ^ a b c FAOSTAT database.

- ^ "FAOSTAT". www.fao.org. Retrieved 2019-10-25.

- ^ a b c d e Sheep, Lamb & Mutton: Background, United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service (last updated May 26, 2012).

- ^ a b College of Agriculture and Home Economics. "Sheep Production and Management" (PDF).

- ^ "The suffering of farmed sheep". Animal Aid. Retrieved 2019-06-04.

- ^ a b c Wooster

- ^ French, N. P.; et al. (1994). "Lamb tail docking: a controlled field study of the effects of tail amputation on health and productivity". Vet. Rec. 134 (18): 463–467. doi:10.1136/vr.134.18.463. PMID 8059511. S2CID 32586633.

- ^ "History of Wool". The Big Merino. Retrieved 2019-08-30.

- ^ "Genetic selection and using Australian Sheep Breeding Values (ASBV)". www.agric.wa.gov.au. Retrieved 2019-08-30.

- ^ "Managing flystrike in sheep". www.agric.wa.gov.au. Retrieved 2019-08-30.

- ^ "preventing flystrike – management". www.agric.wa.gov.au. Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development. 2017.

- ^ Bright, Ashleigh. "The short scrotum method of castration in lambs: a review" (PDF). FAI Farms Ltd.

- ^ MAFF (UK) 2000. Sheep: codes of recommendations for the welfare of livestock. Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, London.

- ^ Canadian Veterinary Medical Association. Position Statement, March 1996.

- ^ Brown, Dave; Meadowcroft, Sam (1996). The Modern Shepherd. Ipswich, United Kingdom: Farming Press. ISBN 978-0-85236-188-7.

- ^ Simmons & Ekarius

- ^ Moule, G.R. (1972). Handbook for Woolgrowers. Australian Wool Board. p. 186.

- ^ "MA000035: Pastoral Award 2010". awardviewer.fwo.gov.au. Retrieved 2019-08-30.

- ^ "Welfare group targets abuse in Australian shearing sheds". ABC News. 10 July 2014. Retrieved 17 September 2014.

- ^ "Sheepmeat market structures and systems investigation" (PDF). Meat and Livestock Australia.

- ^ George Monbiot (October 2013). Feral - Rewilding the land, sea and human life. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-1846147487.

- ^ "Philip Hoare is enchanted by a call for the return of bear, beaver and bison to Britain". The Daily Telegraph. London. 28 May 2013. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

Further reading

[edit]- Carlson, Alvar Ward. "New Mexico's Sheep Industry: 1850–1900, Its Role in the History of the Territory." New Mexico Historical Review 44.1 (1969).

- Fraser, Allan H. H. "Economic aspects of the Scottish sheep industry." Transactions of the Royal Highland and Agricultural Society of Scotland 51 (1939): 39–57.

- Hawkesworth, Alfred. "Australasian sheep & wool.": a practical and theoretical treatise ( W. Brooks & co., ltd., 1900).

- Jones, Keithly G. "Trends in the US sheep industry" (USDA Economic Research Service, 2004).

- Minto, John. "Sheep Husbandry in Oregon. The Pioneer Era of Domestic Sheep Husbandry." The Quarterly of the Oregon Historical Society (1902): 219–247. in JSTOR

- Perkins, John. "Up the Trail From Dixie: Animosity Toward Sheep in the Culture of the US West." Australasian Journal of American Studies (1992): 1–18. in JSTOR

- Witherell, William H. "A comparison of the determinants of wool production in the six leading producing countries: 1949–1965." American Journal of Agricultural Economics 51.1 (1969): 138–158.

External links

[edit] Media related to Ovis aries at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ovis aries at Wikimedia Commons Media related to Sheep shearing at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Sheep shearing at Wikimedia Commons