Shanty town

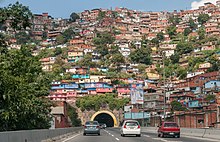

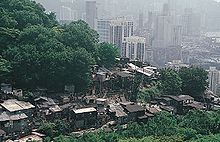

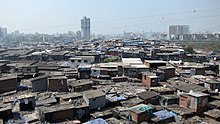

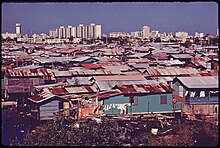

A shanty town, squatter area, squatter settlement, or squatter camp is a settlement of improvised buildings known as shanties or shacks, typically made of materials such as mud and wood, or from cheap building materials such as corrugated tin sheets. A typical shanty town is squatted and in the beginning lacks adequate infrastructure, including proper sanitation, safe water supply, electricity and street drainage. Over time, shanty towns can develop their infrastructure and even change into middle class neighbourhoods. They can be small informal settlements or they can house millions of people.

First used in North America to designate a shack, the term shanty is likely derived from French chantier (construction site and associated low-level workers' quarters), or alternatively from Scottish Gaelic sean (pronounced [ʃɛn]) meaning 'old' and taigh (pronounced [tʰɤj]) meaning 'house[hold]'.

Globally, some of the largest shanty towns are Ciudad Neza in Mexico, Orangi in Pakistan and Dharavi in India. They are known by various names in different places, such as favela in Brazil, villa miseria in Argentina and gecekondu in Turkey. Shanty towns are mostly found in developing nations, but also in the cities of developed nations, such as Athens, Los Angeles and Madrid. Cañada Real is considered the largest informal settlement in Europe, and Skid Row is an infamous shanty town in Los Angeles. Shanty towns are sometimes found on places such as railway sidings, swampland or disputed building projects. In South Africa, squatter camps, often referred to as "plakkerskampe", directly translated from the Afrikaans word for squatter camps, often starts and grows rapidly on vacant land or public spaces within or close to cities and towns, where there may be nearby work opportunities, without the cost of transport.

Construction

[edit]

Shanty towns tend to begin as improvised shelters on squatted land. People build shacks from whatever materials are easy to acquire, for example wood or mud. There are no facilities such as electricity, gas, sewage or running water. The squatters choose areas such as railway sidings, preservation areas or disputed building projects.[1] Swiss journalist Georg Gerster has noted (with specific reference to the invasões of Brasilia) that "squatter settlements [as opposed to slums], despite their unattractive building materials, may also be places of hope, scenes of a counter-culture, with an encouraging potential for change and a strong upward impetus".[2] Stewart Brand has observed that shanty towns are green, with people recycling as much as possible and tending to travel by foot, bicycle, rickshaw or shared taxi, though this is mainly due to the generally poor economic situation found.[3]

Development and future prospects

[edit]

While most shanty towns begin as precarious establishments haphazardly thrown together without basic social and civil services, over time, some have undergone a certain amount of development. Often the residents themselves are responsible for the major improvements.[4] Community organizations sometimes working alongside NGOs, private companies, and the government, set up connections to the municipal water supply, pave roads, and build local schools.[4] Some of these shanties have become middle class suburbs. One such example is the Los Olivos neighbourhood of Lima, Peru, which now contains gated communities, casinos, and plastic surgery clinics.[4]

Some Brazilian favelas have also seen improvements in recent years and can even attract tourists.[5] Development occurs over a long period of time and newer towns still lack basic services. Nevertheless, there has been a general trend whereby shanties undergo gradual improvements, rather than relocation to even more distant parts of a metropolis.[6]

In Africa, many shanty towns are starting to implement the use of composting toilets[7] and solar panels.[8] In India, people living in slums have access to cell phones and the internet.[9]

Other African shanty towns have even become popular tourist attractions. Soweto, an old squatter camp from apartheid-era South Africa is now classified as a city within a city, with a population of almost 2 million. It boasts the popular "Soweto Towers" and a multitude of guided excursions, often including a Shisa-nyama.

Pope Francis argues in his 2015 encyclical letter Laudato si' that shanty town settlements should be developed, if possible, rather than people being moved on and their settlements destroyed. He and the Catholic Church's Council for Justice and Peace have emphasised the need for information, involvement and choice being offered to people being moved on.[10][11]

Instances

[edit]Shanty towns are present in a number of developing countries. In Francophone countries, shanty towns are referred to as bidonvilles (French for "can town"); such countries include Haiti, where Cité Soleil houses between 200,000 and 300,000 people on the edge of Port-au-Prince.[12]

Africa

[edit]In 2016, 62% of Africa's population was living in shanty towns.[13]

Squatter camps in South Africa typically use cheap, and easily acquired building materials such as corrugated tin sheets to build shacks. Offering very little protection against extreme weather conditions, these squatter camps, often built near streams or rivers due to the steady water supply, are often subjected to flash floods. They are also prone to runaway fires due to the close proximity they are built in. They often cause a great deal of damage to naturally occurring ecosystems, both directly, and indirectly. An example of severe indirect damage is the use of washing detergents, and refuse disposal in the nearby water source, which can often be seen for hundreds of kilometers down stream.

Due to the lack of infrastructure, and the cost of basic services, such as water and electricity, the overall squatted area is often barren, with the ground sweeped and stamped to minimise dust, and where gardening is simply impossible and unaffordable. Illegal and dangerous electricity connections are abundant, another danger for fires, and electrical accidents,

The Joe Slovo squatter camp, in Cape Town, houses an estimated 20,000 people.[14] Shack dwellers in South Africa organise themselves in groups such as Abahlali baseMjondolo and Western Cape Anti-Eviction Campaign.[15][better source needed]

In Nairobi, the capital of Kenya, Kibera has between 200,000 and 1 million residents. There is no running water and inhabitants use a flying toilet in which faeces are collected in a plastic bag then thrown away.[16] Mathare is a collection of slums which contain around 500,000 people.[17] In Zambia, the informal housing areas are known as kombonis and approximately 80% of the people in the capital Lusaka are living in them.[18]

Asia

[edit]

The largest shanty town in Asia is Orangi in Karachi, Pakistan, which had an estimated 1.5 million inhabitants in 2011.[16] The Orangi Pilot Project aims to lift local people out of poverty. It was begun by Akhtar Hameed Khan and run by Parveen Rehman until her murder in 2013.[19] Residents laid sewage pipes themselves and almost all of Orangi's 8,000 streets are now connected.[20] In India, an estimated one million people live in Dharavi, a shanty town built on a former mangrove swamp in Mumbai.[16] It is one of the most densely populated places on the globe.[21] In 2011, there were at least four improvised settlements in Mumbai containing even more people.[22] There are in total 3.4 million people living in the 5,000 informal settlements of Bangladesh's capital city Dhaka.[23]

Thailand has 5,500 informal settlements, one of the largest being a shanty town in the Khlong Toei District of Bangkok.[24] In China, 171 urban villages were demolished before the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing.[25] As of 2005, there were 346 shanty towns in Beijing, housing 1.5 million people.[26] Author Robert Neuwirth wrote that around six million people, half the population of Istanbul lived in gecekondu areas.[27]

In Hong Kong, the Kowloon Walled City housed up to 50,000 people,[28] with rooftop slums currently providing some additional housing.

| Part of a series on |

| Living spaces |

|---|

|

Latin America

[edit]The world's largest shanty town is Ciudad Neza or Neza-Chalco-Itza, which is part of the city of Ciudad Nezahualcóyotl, next to Mexico City. Estimates of its population range from 1.2 million to 4 million.[13][16]

Brazil has many favelas. In Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, it was calculated in 2000 that over 20% of its 6.5 million inhabitants were living in more than 600 favelas. For example, Rocinha is home to an estimated 80,000 inhabitants. It has developed into a densely populated neighbourhood with some buildings reaching six storeys high. There are theatres, schools, nurseries and local newspapers.[1]

In Argentina, shanty towns are known as villas miseria. As of 2011, there were 500,000 people living in 864 informal settlements in the metropolitan Buenos Aires area. In Peru, they are known as pueblos jóvenes ("young towns"), as campamentos in Chile, and as asentamientos in Guatemala.

Developed countries

[edit]

During the 1930s Great Depression, shanty towns nicknamed Hoovervilles sprang up across the United States.[29] Following the Great Depression, squatters lived in shacks on landfill sites beside the Martin Pena canal in Puerto Rico and were still there in 2010.[30] More recently, cities such as Newark and Oakland have witnessed the creation of tent cities. The Umoja Village shanty town was squatted in 2006 in Miami, Florida.[31] There are also colonias near the border with Mexico.[32]

Although shanty towns are now generally less common in developed countries in Europe, they still exist. The growing influx of migrants has fuelled shantytowns in cities commonly used as a point of entry into the European Union, including Athens and Patras in Greece.[33] The Calais Jungle in France had grown to over 8,000 people by the time of its clearance in October 2016.[34] Bidonvilles exist in the peripheries of some French cities. The state authorities recorded 16,399 people living in 391 slums across the country in 2012. Of these, 41% lived on the outskirts of Paris.[35]

In Madrid, Spain, a shanty town named Cañada Real is considered the largest informal settlement in Europe. It has an estimated 8,628 inhabitants, who are mainly Spanish, Romani and north African, but only one mobile health unit.[36][37] After 40 years, property developers began to take an interest in the site in 2012.[38]

There have been cardboard cities in London and Belgrade. In some cases, shanty towns can persist in gentrified areas that local governments have yet to redevelop, or in regions of political dispute. A major historical example was the Kowloon Walled City in Hong Kong.[39]

In Australia and New Zealand, there were many shanty towns before World War II, some of which still exist (for example Wyee,[40] a suburb of the Central Coast).

In popular culture

[edit]

Many films have been shot in shanty towns. Slumdog Millionaire centres on characters who spend most of their lives in Indian shanty towns.[41] The Brazilian film City of God was set in Cidade de Deus and filmed in another favela, called Cidade Alta.[42] White Elephant, a 2012 Argentinian movie, is set in a villa miseria in Buenos Aires.[43] The South African film District 9 is largely set in a township called Chiawelo, from which people had been forcibly resettled.[44]

The 2016 Chinese TV series Housing tells the story of shantytown clearance in Beiliang, Baotou, Inner Mongolia.[45]

A 2023 Nigerian crime thriller titled Shanty Town was released on Netflix on January 20, 2023. It is a six-part series that tells the story of a ruthless leader named Scar (Chidi Mokeme) who handles a lot of dirty business and is popularly regarded as the King of Shanty Town.[46]

Video games such as Max Payne 3 have levels located in fictional shanty towns.[47]

Reggae singer Desmond Dekker sang a song called "007 (Shanty Town)".[48]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Caves, R. W. (2004). Encyclopedia of the city. Routledge. p. 176. ISBN 0-415-25225-3.

- ^ Gerster, Georg (1978). Flights of Discovery: The Earth from Above. London: Paddington. p. 116.

- ^ Stewart Brand,Stewart Brand on New Urbanism and squatter communities Archived 2011-03-20 at the Wayback Machine, The New Urban Network, reprinted from Whole Earth Discipline, Penguin.

- ^ a b c "Some "Young Towns" in Lima Not So Young Anymore". COHA Staff. Archived from the original on 23 August 2011. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ^ Clarke, Felicity (May 16, 2011). "Favela Tourism Provides Entrepreneurial Opportunities in Rio". Forbes. Archived from the original on July 29, 2017. Retrieved September 11, 2017.

- ^ "Informality: Re-Viewing Latin American Cities". Archived from the original on 22 July 2015. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ^ Thomson Reuters Foundation. "Thomson Reuters Foundation". Archived from the original on 16 April 2013. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ^ "Youth Bring Low-Cost Solar Panels to Kenyan Slum". Archived from the original on 22 July 2015. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ^ "IT for schools, Schools, Education, Technology, UK news, Online learning e-learning (Education)". The Guardian. London. May 8, 2001. Archived from the original on March 5, 2017. Retrieved December 13, 2016.

- ^ Pope Francis (2015), Laudato si', paragraph 152, accessed 16 February 2024

- ^ Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace (2004), Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church, paragraph 482, accessed 16 February 2024

- ^ "Cité-Soleil: Grinding poverty, relentless violence". International Committee of the Red Cross. Archived from the original on 2007-09-30. Retrieved 2007-08-16.

- ^ a b Totaro, Paola (17 October 2016). "Slumscapes: How the world's five biggest slums are shaping their futures". Reuters. Archived from the original on 1 May 2019. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ "Gateway housing project in a shambles". The Times. 23 Nov 2008. Archived from the original on 15 February 2009. Retrieved 23 November 2008.

- ^ Losier, Toussaint (2010). "A Quiet Coup: South Africa's largest social movement under attack as the World Cup Looms". Desinformémonos. Archived from the original on 28 June 2019. Retrieved 30 May 2020. Originally published in Spanish at Desinformémonos.

- ^ a b c d Tovrov, Daniel (9 December 2011). "5 Biggest Slums in the World". International Business Times. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ Gettleman, Jeffrey (10 November 2006). "Chased by Gang Violence, Residents Flee Kenyan Slum". The New York Times. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ Chigunta, Francis; Gough, Katherine V.; Langevang, Thilde (2016). "Young entrepreneurs in Lusaka: Overcoming constraints through ingenuity and social entrepreneurship". In Gough, Katherine V.; Langevang, Thilde (eds.). Young Entrepreneurs in Sub-Saharan Africa. Routledge Spaces of Childhood and Youth Series. Routledge. pp. 67–79. ISBN 978-1-317-54837-9.

- ^ "Pakistan mourns murdered aid worker". BBC News. 14 March 2013. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ "These are the world's five biggest slums". World Economic Forum. 19 October 2016. Archived from the original on 29 April 2020. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ "10 famous slums in the world and the challenges they face". The Straits Times. 24 July 2014. Archived from the original on 9 December 2017. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ Lewis, Clara (6 July 2011). "Dharavi in Mumbai is no longer Asia's largest slum". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 23 November 2019. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ "ISUH home" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 February 2013. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ^ "Bangkok's Klong Toey Slum". Borgen Magazine. 28 April 2014. Archived from the original on 18 December 2019. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ Ma, Josephine (22 July 2008). "Demolitions limit slum villages to city Outskirts". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 2 May 2009. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ "People's Daily Online -- "Slums" sting Chinese cities, hamper building of harmonious society". Archived from the original on 6 December 2013. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ^ Neuwirth, Robert (2004). Shadow cities : a billion squatters, a new urban world. Routledge. p. 8. ISBN 0-415-93319-6.

- ^ "Life Inside The Most Densely Populated Place On Earth [Infographic]". Popular Science. 2019-03-18. Retrieved 2021-05-24.

- ^ Gregory, James (2009). "Hoovervilles and Homelessness". Civil Rights and Labor History Consortium. University of Washington. Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ What America Looked Like: Puerto Rican Slums in the Early 1970s Archived 2016-12-20 at the Wayback Machine The Atlantic (July 17, 2012)

- ^ Samuels, Robert (24 October 2007). "Housing Activists Try Squatter Strategy". Miami Herald. Archived from the original on 29 February 2012. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ "Colonias FAQ's (Frequently Asked Questions)". Texas Secretary of State. Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Office of Community Affairs. Archived from the original on 9 October 2008. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ Squires, Nick; Anast, Paul (September 7, 2009). "Greek immigration crisis spawns shanty towns and squats". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on June 24, 2018. Retrieved April 5, 2018.

- ^ "Calais 'Jungle' cleared of migrants, French prefect says". BBC News. 26 October 2016. Archived from the original on 27 June 2019.

- ^ Aguilera, Thomas (2017). "Everyday resistances in French slums". In Chattopadhay, Sutapa; Mudu, Pierpaolo (eds.). Migration, squatting and radical autonomy. Routledge. p. 132. ISBN 978-1-138-94212-7.

- ^ García Gallo, Bruno (March 12, 2012). "Cañada Real, censo definitivo: 8.628 personas". El País. Madrid. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ Fotheringham, Alasdair (November 27, 2011). "In Spain's heart, a slum to shame Europe". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on September 14, 2017. Retrieved September 11, 2017.

- ^ Showdown Looms Over Europe's Largest Shantytown Archived 2018-06-22 at the Wayback Machine LAUREN FRAYER, National Public Radio (Washington DC), April 27, 2012.

- ^ "Kowloon Walled City Park". Archived from the original on 7 February 2010. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ "Inside the 100-year-old 'shantytown' almost unchanged since WWI". ABC News. 6 October 2017.

- ^ Roston, Tom (11 April 2008). "'Slumdog Millionaire' shoot was rags to riches". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 27 August 2019. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ Vieira, Karina; Watts, Jonathan; Kaiser, Anna (9 June 2014). "How we made City of God". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 9 January 2019. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ Robey, Tim (25 April 2013). "White Elephant, review". Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 28 November 2017. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ Woerner, Meredith (19 August 2009). "5 Things You Didn't Know About District 9". io9. Archived from the original on 25 April 2020. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ Wei, Lu (17 October 2016). "Housing tells story of shantytown clearence [sic][1]". China Daily. Archived from the original on 4 May 2020. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ Shanty town at IMDb. Retrieved 2023-05-02.

- ^ Parker, Laura (17 October 2012). "Max Payne 3 hostage negotiation DLC landing October 30". GameSpot. Archived from the original on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ 007 (Shanty Town) by Desmond Dekker - Track Info | AllMusic, retrieved 2023-06-16

Further reading

[edit]- Daniel Carter Beard (1920). Shelters, shacks, and shanties. C. Scribner's Sons. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- Slate article about an economist proposing New Orleans to be reconstructed with shanties