Yan'an Soviet

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Chinese. (January 2022) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

| Shaan-Gan-Ning Border Region 陝甘寧邊區 | |

|---|---|

| Rump state of the Chinese Soviet Republic | |

| 1937–1950 | |

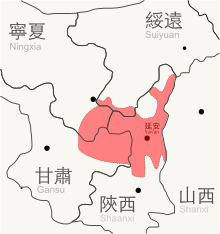

Map of Shaan-Gan-Ning Border Region. | |

| Capital | Yan'an (1937–47, 1948–49) Xi'an (1949–50) |

| Area | |

• 1937 | 134,500 km2 (51,900 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 1937 | 1,500,000 |

| Government | |

| Chairman | |

• 1937–1948 | Lin Boqu |

| Deputy Chairman | |

• 1937–1938 | Zhang Guotao |

• 1938–1945 | Gao Zili |

| Historical era | Chinese Civil War |

• Established | 6 September 1937 |

• Disestablished | 19 January 1950 |

| Today part of | China |

The Yan'an Soviet was a soviet governed by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) during the 1930s and 1940s.[1] In October 1936 it became the final destination of the Long March, and served as the CCP's main base until after the Second Sino-Japanese War.[2]: 632 After the CCP and Kuomintang (KMT) formed the Second United Front in 1937, the Yan'an Soviet was officially reconstituted as the Shaan–Gan–Ning Border Region (traditional Chinese: 陝甘寧邊區; simplified Chinese: 陕甘宁边区; pinyin: Shǎn gān níng Biānqū; Wade–Giles: Shan3-kan1-ning2 Pien1-ch'ü1).[a][3]

Organization

[edit]The Shaan-Gan-Ning base area, of which Yan'an was a part, was founded in 1934.[4]: 129

During the Second Sino-Japanese War, the Shaan-Gan-Ning Border Region became one of a number of border region governments established by the Communists. Other regions included the Jin-Sui Border Region (in Shanxi and Suiyuan),[b] the Jin-Cha-Ji Border Region (in Shanxi, Chahar, and Hebei) and the Ji-Lu-Yu Border Region (in Hebei, Henan and Shandong).

Although not on the front lines of the Second Sino-Japanese War, the Shaan-Gan-Ning Border Region was the most politically important and influential revolutionary base area due to its function as the de facto capital of the Chinese Communist Revolution.[5]: 129

Economy

[edit]Immediately after setting up the Soviet, the CCP began their "land revolution", confiscating property en-masse from the landlords and gentry of the region.[3]: 265 Its vigour in doing so resulted from two factors, its ideological commitment to peasant revolution and economic necessity. The base area's economic situation was precarious.[4]: 129 , such that in 1936 the entire Soviet's revenue stood at just 1,904,649 yuan, of which some 652,858 yuan came from confiscation of property.[3]: 266 The program of land redistribution, the party's hostility towards merchants and its ban on opium depressed the local economy severely, and by 1936 the Communists were reduced to raiding nearby Shanxi (then ruled by Nationalist-backed warlord Yan Xishan) in order to acquire grain and other supplies.[3]: 266 The tightening of the Nationalist blockade in the same year made it difficult to secure resources from outside the region.[4]: 129 At no point during the period 1934-1941 was the Yan'an Soviet financially solvent, being dependent first on the confiscation of property from "enemy classes" and then on Nationalist aid,[3]: 265 the latter of which comprised around 70% of the Soviet's revenue from 1937 to 1940. [3]: 269

The blockade decreased during the Second United Front, but the Nationalists intensified it after military hostilities began again in 1941.[4]: 129 Japanese assaults in the region and poor harvests worsened the effects of blockade and the region had a severe economic crisis in 1941 and 1942.[4]: 130 By 1944, the region had suffered cumulative inflation of 564,700% since 1937, compared with 75,550% in Nationalist areas.[6] CCP leaders raised the issue of abandoning the area, which Mao Zedong refused to do.[4]: 130 Mao implemented a mass line strategy,[4]: 130 and imposed heavy taxes on the population in order to pay military expenses, which resulted in what is known as the "Yan'an Way", establishing the Border Region's independence from Nationalist subsidy.[6] However, the economy of the Border Region was also substantially supported by the production and export of opium into Japanese and Nationalist areas,[6] with academic Chen Yung-fa arguing that the economy of the Border Region was so dependent on opium that, had the CCP not engaged in opium trading, the so-called "Yan'an Way" would have been impossible.

Media

[edit]In January 1937, American journalist Agnes Smedley visited Yan'an.[7]: 165–166 In April, Helen Foster Snow traveled to Yan'an for research, interviewing Mao and other leaders.[7]: 166

The Eighth Route Army established its first film production group in the Yan'an Soviet during September 1938.[8]: 69

Yuan Muzhi arrived in Yan'an in fall 1938.[4]: 128 With Wu Yinxian, Yuan made a feature-length documentary, Yan'an and the Eighth Route Army, which depicted the Eighth Route Army's combat against the Japanese.[4]: 128 They also filmed Norman Bethune performing surgeries close to the front lines.[4]: 128

In 1943, the CCP released their first campaign film, Nanniwan, which sought to develop relationships between the CCP army and local people in the Yan'an area by showcasing the army's production campaign to alleviate material shortages.[4]: 16

In 1944, the CCP welcomed a large group of foreign (primarily American) journalists to Yan'an.[7]: 17 In an effort to contrast the party with the Nationalists, the CCP generally did not censor these foreign reports.[7]: 17 In December 1945, the party's Central Committee instructed the party to facilitate the work of American journalists out of the hope that it would have a progressive influence on American policies toward China.[7]: 17–18

Diplomacy

[edit]After the US entry into World War II, the CCP sought military support from the US.[7]: 15 Mao welcomed the American Military Observation Group in Yan'an and in 1944 invited the US to establish a consulate there.[7]: 15

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Postal romanization: Shen–Kan–Ning. The name comes from the Chinese abbreviations of Shaanxi, Gansu, and Ningxia provinces.

- ^ Suiyuan is no longer a province, being incorporated into Inner Mongolia in 1954.

Citations

[edit]- ^ "The Yan'an Soviet". 18 September 2019.

- ^ Van Slyke, Lyman (1986). "The Chinese Communist movement during the Sino-Japanese War 1937–1945". In Fairbank, John K.; Feuerwerker, Albert (eds.). Republican China 1912–1949, Part 2. The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 13. Cambridge University Press. pp. 609–722. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521243384.013. ISBN 9781139054805.

- ^ a b c d e f Saich, Tony; Van De Ven, Hans J. (2015-03-04). "The Blooming Poppy under the Red Sun: The Yan'an Way and the Opium Trade". New Perspectives on the Chinese Revolution (0 ed.). Routledge. pp. 263–297. doi:10.4324/9781315702124. ISBN 978-1-317-46391-7. OCLC 904437646.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Qian, Ying (2024). Revolutionary Becomings: Documentary Media in Twentieth-Century China. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231204477.

- ^ Opper, Marc (2020). People's Wars in China, Malaya, and Vietnam. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. doi:10.3998/mpub.11413902. hdl:20.500.12657/23824. ISBN 978-0-472-90125-8. JSTOR 10.3998/mpub.11413902. S2CID 211359950.

- ^ a b c Mitter, Rana (2013). "Hunger in Henan". China's War with Japan (1 ed.). Penguin Books. pp. 279–280.

- ^ a b c d e f g Li, Hongshan (2024). Fighting on the Cultural Front: U.S.-China Relations in the Cold War. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. doi:10.7312/li--20704. ISBN 9780231207058. JSTOR 10.7312/li--20704.

- ^ Li, Jie (2023). Cinematic Guerillas: Propaganda, Projectionists, and Audiences in Socialist China. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231206273.