History of concubinage in the Muslim world

| Part of a series on |

| Forced labour and slavery |

|---|

|

Concubinage in the Muslim world was the practice of Muslim men entering into intimate relationships without marriage,[2] with enslaved women,[3] though in rare, exceptional cases, sometimes with free women.[4][5][6] If the concubine gave birth to a child, she attained a higher status known as umm al-walad.[7]

It was a common practice in the Ancient Near East for the owners of slaves to have intimate relations with individuals considered their property,[a] and Mediterranean societies, and had persisted among the three major Abrahamic religions, with distinct legal differences, since antiquity.[8][9][b] Islamic law has traditionalist and modern interpretations,[10] and while the former historically allowed men to have sexual relations with their female slaves,[11][12] most modern Muslims and Islamic scholars consider slavery in general and slave-concubinage to be unacceptable practices.[13]

Concubinage was widely practiced throughout the Umayyad, Abbasid, Mamluk, Ottoman, Timurid and Mughal Empires. The prevalence within royal courts also resulted in many Muslim rulers over the centuries being the children of concubines. The practice of concubinage declined with the abolition of slavery.[14]

Characteristics

[edit]

Classifications of concubinage often defines practices in Islamic societies as a distinct variant. In one reading, there are three cultural patterns of concubinage: European, Islamic and Asian.[15] Concubinage has also been categorised in terms of form and function, which in the Islamic world varied between times and places. The International Encyclopedia of Anthropology gives four distinct forms of concubinage,[16] three of which are applicable to the Muslim Word: 'elite concubinage', where concubine ownership was primarily related to social status, such as under the Umayyads; royal concubinage, where concubines became consorts to the ruler and perpetuated the royal bloodline and politics and reproduction were deeply intertwined, including under the Abbasids and in the Ottoman empire; and concubinage as a patriarchal function where concubines were of low status and the children of concubines became permanently inferior to the children of wives, such as in Mughal India.[16]

The expansion of various Muslim dynasties resulted in the acquisitions of concubines, through purchase, gifts from other rulers, and captives of war. To have a large number of concubines became a symbol of status.[17] While Muslim soldiers in the early Islamic conquests were given female captives as a reward for military participation, they were later frequently purchased and men were permitted to have as many concubines as they could afford. As slaves for pleasure were expensive, they were typically the preserve of privileged elites.[18]

The concubines of Islamic rulers could achieve considerable power,[19] and often enjoyed higher status than other slaves. Abu Hanifa and others argued for the extension of Islamic modesty practices to concubines, recommending that the concubine be established in the home and their chastity be protected from friends or kin.[20] Most Islamic schools of thought restricted concubinage to a relationship where the female slave was required to be monogamous to her master.[21] While scholars exhorted masters to treat their slaves equally, a master was allowed to show favoritism towards a concubine.[20] Some scholars recommended holding a banquet (walima) to celebrate the concubinage relationship, though not required by the teachings of Islam.[20]

In slave-owning societies, most concubines were slaves, but not all.[19] Concubines were typically freed after giving birth in the Muslim world, as in about one-third of non-Islamic slave-holding societies.[c] In Islamic culture, a slave who bore a child to a free man was known as an umm al-walad, could not be sold, and, in most circumstances, at her owner's death, was freed.[22] The children of concubines in Islamic societies were generally declared as legitimate.[20] Among societies that did not legally require the manumission of concubines, it was often done anyway.[citation needed]

Almost all Abbasid caliphs were born to concubines and several Twelver Shia imams were also born to concubines.[citation needed] The Ottoman sultans also appeared to have preferred concubinage to marriage,[23] and for a time all royal children were born of concubines.[24] Over time, the concubines of the Imperial Harem came to exercise a considerable degree of influence over Ottoman politics.[17] The consorts of Ottoman sultans were often neither Turkish, nor Muslim by birth, and it has been argued that this was intentional so as to limit the political leverage a concubine might possess as compared to a princess or a daughter of the local elite.[25] Ottoman sultans also appeared to have only one son with each concubine, and after a concubine gave birth to a son, would no longer have intercourse with them. This also limited the power of each concubine and son.[26] Even so, many concubines developed social networks, and accumulated personal wealth, both of which allowed them to rise in terms of social status.[citation needed] The practice declined with the abolition of slavery, starting in the 19th century.[17]

Islamic legal positions

[edit]

Enslavement

[edit]

The enslavement of other Muslims was expressly forbidden by Islamic jurists.[27] However, in times of war, non-Muslims who were captured in battle could be enslaved,[28] and the population of a conquered territory could also be enslaved, paving the way for concubinage.[29] During the early Muslim conquests, capture in war was a major source of concubines, but this source declined to a very small proportion later on.[30] Enslavement was intended both as a form of humiliation to the defeated for previous or continuing disbelief,[31] and as a debt.[29] However, non-Muslims could not be enslaved if they were either residents of a Muslim state (dhimmis) or protected foreign visitors (mustamin).[32][18] The sexual relationship between a concubine and her master was viewed as a debt upon the woman until she gave birth to her master's child and the master's later death.[33] Some men purchased female slaves, whereas Muslim soldiers in the early Islamic conquests were given female captives as a reward for military participation. Men were permitted to have as many concubines as they could afford, but as slaves for pleasure were expensive, they were typically an elite privilege.[18]

At the same time, the Qur'an and the hadith traditions hailed the manumission of slaves as a virtue that would be rewarded in the afterlife.[d] Some jurists argued that prisoners were either to be enslaved or killed. Others maintained that a Muslim military commander could choose between unconditionally releasing, ransoming or enslaving these war captives.[e] Later on in Muslim history, the purchase of slaves from outside the Muslim world became the most important source of concubines.[30] Hereditary slavery, though technically possible,[34] was rarely practiced in the Muslim world.[35][36][37] Slave-girls by descent are those that are born to slave mothers.[11] Although a slave girl who bore children to their master bore free children, owners who would marry off their female slaves to someone else, would be the masters of any children born from that marriage too.[38]

- Exceptions

Despite the Islamic prohibition, there were historical instances where Muslims enslaved Muslims from other ethnic groups.[27] In the 12th century, amid internecine war in Al-Andalus, the Umayyad caliph Muhammad II of Córdoba ordered that Berber women in Cordoba be captured and sold. The Berber Almohads in turn captured and sold Umayyad women.[39] There are also reports of Ottoman generals enslaving Mamluk wives and girls in the Ottoman–Mamluk War (1516–1517), and in 1786–87, in the region of modern-day Chad, Muslim women and children from the Sultanate of Bagirmi were likewise enslaved by the ruler of Wadai around 1800.[40]

Social rights

[edit]Islamic law obliged slave owners to provide their female slaves with food, clothing, and shelter, and gave female slaves protection from sexual exploitation by anyone who was not their owner.[41] If she bore her master a child and if he accepted paternity she could obtain the position of an Umm walad. Separately, if someone bought a woman with child, they could not be separated until, according to Ibn Abi Zayd, the child was six years old.[42] However, while slave concubines could rise to positions of influence, these position did not legally protect them from forced labour, forced marriage and sex, and even elite slaves were still traded as chattel.[41]

As sexual commodities, female slaves were, in some historical periods, not allowed to cover themselves in the fashion of free women.[43] The Caliph Umar prohibited slave girls from resembling free women and forbade them from covering their face.[44] Slave women were also not required to cover their arms, hair or legs below the knees.[45] Myrne writes Islamic jurists required female slaves to cover their whole body (except face and hands).[46] There is disagreement over what Hanafi jurists allowed: according to Ibn Abidin most Hanafi scholars did not allow the exposure of a female slave's body (including chest or back),[47] but Myrne writes they allowed this in the case of potential male buyers.[46] Amira Bennison writes that, during the Abbasid period, male buyers could not in practice examine female slaves (except her face and hands), but could request her examination by other women.[48]

In accordance with their lesser status, if a slave fornicated they received less punishment than a free woman. Female slaves could also be traded freely among many men, with few, if any, apparent restrictions.[49] While bearing a master's child could lead to freedom for a slave-girl, the motive that this gave female slaves to have sex with their owners was a cause of regular opposition to concubinage from free wives, and early moral stories depicted wives as the victims of concubinage.[50] While a free Muslim woman was considered to be a man's honour, a slave-girl was merely property and not a man's honour.[51]

Medieval Muslim literature and legal documents show that those female slaves whose main use was for sexual purposes were distinguished in markets from those whose primary use was for domestic duties. The term suriyya was used for female slaves with whom masters enjoyed sexual relations. The Arabic term surriyya has been widely translated in Western scholarship as "concubine"[52][53][54][55] or "slave concubine".[53] In other texts they are referred to as "slaves for pleasure" or "slave-girls for sexual intercourse".[56] It was not a secure status as the concubine could be traded as long as the master had not impregnated her.[57] Many female slaves became concubines to their owners and bore their children. Others were just used for sex before being transferred. The allowance for men to use contraception with female slaves assisted in thwarting unwanted pregnancies.[56] Withdrawal before ejaculation (azl) did not require the consent of the slave.[58] Islamic law and Sunni ulama historically recognised two categories of concubines.[11]

Umm walad

[edit]Umm walad (Arabic: أم ولد, lit. 'mother of the child') was the title given to a slave-concubine in the Muslim world after she had born her master a child. She could not be sold, and became automatically free on her master's death.[59][60] The offspring of an umm walad were free and considered legitimate children of their father, including full rights of name and inheritance.[60] The Sunni law schools disagreements existed among some of the four major schools of Sunni law regarding the concubine's entitlement to this status. Hanafi jurists state that the umm walad status is contingent on the master acknowledging paternity of the child. If he does not accept that he is the father of the child then both the mother and child remain slaves. Maliki jurists ruled that the concubine becomes entitled to the status of umm walad even if her master did not acknowledge that the child is his.[61] This is decidedly different from the case of enslaved women who bore children to their masters in Mediterranean Christian cultures: there the child retained the same slave status as his mother.[f] The offspring of slave relationships could rise to great eminence, with no prejudice attached to their origins: most of the caliphs of the Abbasid Caliphate were born from relationships with enslaved concubines as were half of the imams of Imami Shi'ism.[g]

Sexual consent

[edit]

Classical Islamic family law generally recognized marriage and the creation of a master–slave relationship as the two legal instruments rendering permissible sexual relations between people and classical Islamic jurists made an analogy between the marriage contract and sale of concubines. They state that the factor of male ownership in both is what makes sex lawful with both a wife and female slave.[62][58] Hina Azam notes that in certain interpretations of Islamic law "coercion within marriage or concubinage may be repugnant, but it remained fundamentally legal".[63] According to Kecia Ali, the Qurʾanic passages on slavery differ strikingly in terms of their terminology and main preoccupations compared to the jurisprudential texts, that the text of the Qurʾan does not permit sexual access simply by the virtue of her being a milk al-yamīn or concubine while the "Jurists define zina as vaginal intercourse between a man and a woman who is neither his wife nor his slave. Though seldom discussed, forced sex with one's wife might (or, depending on the circumstances, might not) be an ethical infraction, and conceivably even a legal one like assault if physical violence is involved. One might speculate that the same is true of forced sex with a slave. This scenario is never, however, illicit in the jurists' conceptual world".[58]

Responding to a query about whether a man can be forced to have intercourse or if it is obligatory for him to have intercourse with his wife or concubine, Imam Al-Shafiʽi stated "If he has only one wife or an additional concubine with whom he has intercourse, he is commanded to fear Allah Almighty and to not harm her in regards to intercourse, although nothing specific is obligated upon him. He is only obligated to provide what benefits her such as financial maintenance, residence, clothing, and spending the night with her. As for intercourse, its position is one of pleasure and no one can be forced into it."[64][65] The statement is sometimes popularly misunderstood to concern the consent of enslaved women.[66]

Another viewpoint is of Rabb Intisar, who argues that according to the Quran, sexual relations with a concubine were subject to both parties' consent.[67] Similarly Tamara Sonn writes that consent of a concubine was necessary for sexual relations.[68] However, according to Kecia Ali, the Qurʾanic passages on slavery differ strikingly in terms of their terminology and main preoccupations compared to the jurisprudential texts, that the text of the Qurʾan does not permit sexual access simply by the virtue of her being a milk al-yamīn or concubine while among jurists notes that such views are not found in any pre-modern classical Islamic legal text between the 8th to 10th centuries, as there is no discussion about the topic of consent.[69] Jonathan Brown argues that the modern conception of sexual consent only came about since the 1970s, so it makes little sense to project it backwards onto classical Islamic law. Brown notes that premodern Muslim jurists rather applied the harm principle to judge sexual misconduct, including between a master and concubine.[70] He further states that historically, concubines could complain to judges if they were being sexually abused and that scholars like al-Bahūtī require a master to set his concubine free if he injures her during sex.[71]

All four law schools also have a consensus that the master can marry off his female slave to someone else without her consent. A master can also practice coitus interruptus during sex with his female slave without her permission.[72] A man having sex with someone else's female slave constitutes zina.[73]

According to Imam Shafi'i, if someone other than the master coerces a slave-girl to have sex, the rapist will be required to pay compensation to her master.[74] If a man marries off his own female slave and has sex with her even though he is then no longer allowed to have sexual intercourse with her, that sex is still considered a lesser offence than zina and the jurists say he must not be punished. It is noteworthy that while formulating this ruling, it is the slave woman's marriage and not her consent which is an issue.[73]

- Conversion of pagans

Islam prohibited sexual relations between Muslim men and pagan female captives.[75] In the early Muslim period, this appeared to delegitimize Muslim captors who wished to form relationships with female captives. To resolve this, coercion into Islam was tacitly permitted. Ibn Hanbal noted that if idolatrous women could be coerced into becoming Muslim, sexual relations with them were permissible, while if they did not embrace Islam, they could be used as servants, but not for sexual relations.[75] Hasan al-Basri recalled that Muslims achieved this objective through various methods, including pointing a pagan slave-girl towards the Kaaba, ordering them to recite the shahada and perform an ablution.[75] Other scholars specified that slave-girls must be taught to pray and perform ablutions by themselves before being considered eligible for sexual relations.[75]Ibn Qayyim argued that conversion of polytheist women to Islam was not necessary for sexual relations with her.[76]

Practice in the Middle East & Europe

[edit]

While Muslim cultures acknowledged concubinage, as well as polygamy, as a man's legal right, in reality, these were usually practiced only by the royalty and elite sections of society.[15] The large-scale availability of women for sexual slavery had a strong influence on Muslim thought, even though the "harem" culture of the elite was not mirrored by most of the Muslim population.[77]

Early Islam

[edit]Concubinage was rare in Arabia in the period immediate preceding the advent of Islam. One analysis of the information found there were only a few cases of children being born from concubines in the time of Muhammad's father and grandfather.[78] With the early Muslim conquests, concubinage expanded rapidly as a practice due to the wealth and power they brought to the Quraysh tribes.[h] Due to these conquests, a large number of female slaves became available and births from concubines arose.[80] A study of the Arab genealogical text Nasab Quraysh records the maternity of 3,000 Quraishi tribesmen, most of whom lived in between 500 and 750 CE. The data shows that there was a massive increase in the number of children born to concubines with the emergence of Islam.[80]

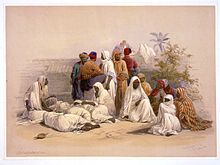

Women of Hawazin

[edit]The Banu Thaqif and Banu Hawazin tribes decided to go to war against Muhammad under the leadership of Malik ibn Awf.[81] Malik had the unfortunate idea of bringing the women, children and livestock with his army.[82] He believed that by bringing their women and children with the army, all his soldiers would fight more courageously to defend them.

The Muslim army defeated the Hawazin and captured their women and children and the pagan soldiers fled. The war booty which the Muslims obtained was 24,000 camels, more than 40,000 goats, 160,000 dirhams worth of silver and 6,000 women and children.[81] Muhammad waited for the Hawazin to come to him to reclaim their families and properties. However, none of them came. Finally, Muhammad distributed the war booty among the Muslim soldiers.[81] Anecdotes include those of one woman was given to Abd al-Rahman ibn Awf who resisted having sexual intercourse with her until her menses were over and then he had sex with her by virtue of her being his property. Jubayr bin Mu'tim also received a slave girl, who was not impregnated. Talha ibn Ubaydullah had sexual intercourse with the female captive given to him. Abu Ubaydah ibn Jarrah impregnated the slave girl he was given.[83]

A delegation from the Hawazin tribe came to Muhammad and converted to Islam. Muhammad granted a general pardon against those who fought the Muslims at Hunayn.

Muhammad returned their women and children and their properties to them.[84] The girl who had been given to Abd al-Rahman ibn Awf was given a choice to stay with him or return to her family. She chose her family. Likewise, the girls given to Talha, Uthman, Ibn Umar and Safwan bin Umayya were also returned to their families.[85] Zaynab chose to return to her husband and cousin.[86] However, the girl who had been given to Saad ibn Abi Waqas chose to stay with him. Uyanya had taken an old woman. Her son approached him to ransom her for 100 camels. The old woman asked her son why would he pay 100 camels when Uyanya would leave her anyway without taking ransom. This angered Uyanya.[85] Uyaynah had earlier said at the Siege of Ta'if that he only came to fight for Muhammad so he could get a Thaqif girl and impregnate her so that she might bear him a son because Thaqif are clever (or fortunate) people.[87][88] When Umar told Muhammad about Uyayna's comment, Muhammad smiled and said "[The man exhibits] an acceptable foolishness".[89][88]

Umayyad Caliphate

[edit]The expansion of concubinage under the Umayyad period was motivated mainly by the Umayyad tribal desire for sons rather than sanction for it in the Quran and Prophetic practice.[90] Concubinage was allowed among the Sassanian elites and the Mazdeans but the children from such unions were not necessarily regarded as legitimate.[91] The position of Jewish communities is unclear although slave concubinage is mentioned in Biblical texts. Apparently, the practice had declined long before Muhammad. Some Jewish scholars during Islamic rule would forbid Jews from having sex with their female slaves.[91] Leo III in his letter to Umar II accused Muslims of "debauchery" with their concubines who they would sell "like dumb cattle" after having tired of using them.[91] One Umayyad ruler, Abd al-Rahman III, was known to have possessed more than 6000 concubines.[92]

The hajin half-Arab sons of Muslim Arab men and their slave concubines were viewed differently depending on the ethnicity of their mothers. Abduh Badawi noted that "there was a consensus that the most unfortunate of the hajins and the lowest in social status were those to whom blackness had passed from their mothers", since a son of African mother more visibly recognizable as non-Arab than the son of a white slave mother, and consequently "son of a black woman" was used as an insult, while "son of a white woman" was used as a praise and as boasting.[93]

Abbasid Caliphate

[edit]The royals and nobles during the Abbasid Caliphate kept large numbers of concubines. The Caliph Harun al-Rashid possessed hundreds of concubines in his harem. The Caliph al-Mutawakkil was reported to have owned four thousand concubines.[92] Slaves for pleasure were costly and were a luxury for wealthy men. In his sex manual, Ali ibn Nasr promoted experimental sex with female slaves on the basis that free wives were respectable and would feel humiliated by the use of the sex positions described in his book because they show low esteem and a lack of love from the man.[18] Women preferred that their husbands keep concubines instead of taking a second wife. This was because a co-wife represented a greater threat to their position. Owning many concubines was perhaps more common than having several wives.[94]

The child of a slave was born in to slavery unless an enslaver chose to awknowledge the child of a slave as his. A male enslaver could choose to officially awknowledge his son with his concubine if he wished to do so. If he choose to do so, the child would be automatically manumitted. During the preceding Umayyad dynasty, sons born of wives and sons born of female slaves where not treated as equals: while the Umayyad Caliphs could awknowledge their sons with slave concubines, slave sons where not considered suitable as heirs to the throne until during the Abbasid dynasty.[95] During the Abbasid dynasty, a number of Caliphs where the awknowledged sons of slave concubines. During the Abbasid era, appointing the acknowledged sons of slave concubines as heirs became common, and from the 9th-century onward, acquiring male heirs through a slave concubine became a common custom for Abbasid citizens.[96]

If a man choose to awknowledge the child of a female slave as his, the slave mother became an umm walad. This meant that they could no longer sold and where to become manumitted upon the death of their enslaver; during the first centuries of Islam, umm walad-slaves where still bought and sold and rented out until the death of their enslaver, but during the Abbasid era this slowly stopped.[97]

Female slaves were graded sexually depending on their race by contemporary slave dealers and authors. Jābir ibn Ḥayyān wrote in the 9th-century:

- "Byzantines have cleaner vaginas than other female slaves have. Andalusians […] are the most beautiful, sweet-smelling and receptive to learning […] Andalusians and Byzantines have the cleanest vaginas, whereas Alans (Lāniyyāt) and Turks have unclean vaginas and get pregnant easier. They have also the worst dispositions. Sindhis, Indians, and Slavs (Ṣaqāliba) and those similar to them are the most condemned. They have uglier faces, fouler odor, and are more spiteful. Besides, they are unintelligent and difficult to control, and have unclean vaginas. East Africans (Zanj) are the most heedless and coarse. If one finds a beautiful, sound and graceful woman among them, however, no their species can match her. […] Women from Mecca (Makkiyāt) are the most beautiful and pleasurable of all types."[98]

Al-Andalus empires

[edit]In Al-Andalus, the concubines of the Almoravid and Almohad Muslim elite were usually non-Muslim women from the Christian areas of the Iberian peninsula. Many of these had been captured in raids or wars and were then gifted to the elite Muslim soldiers as war booty or were sold as slaves in Muslim markets.[99] In Muslim society in general, monogamy was common because keeping multiple wives and concubines was not affordable for many households. The practice of keeping concubines was common in the Muslim upper class. Muslim rulers preferred having children with concubines because it helped them avoid the social and political complexities arising from marriage and kept their lineages separate from the other lineages in society.[99]

In the 11th century, Christian forces in Al-Andalus captured Muslim women in turn, and included eight-year-old Muslim virgins as part of their war booty.[100] and kept them as concubines.[101] When Granada passed from Muslim rule to Christian rule, thousands of Moorish women were enslaved and trafficked to Europe.[102] Muslim families tried to ransom their daughters, mothers and wives who had been captured and enslaved.[103] For both Christians and Muslims, the capture of women from the other religion was a show of power, while the capture and sexual use of their own women by men of the other religion was a cause of shame.[99]

The most famous of the Andalusian harems was perhaps the harem of the Caliph of Cordoba. Except for the female relatives of the Caliph, the harem women consisted of his slave concubines. The slaves of the Caliph were often European saqaliba slaves trafficked from Northern or Eastern Europe. While male saqaliba could be given work in a number offices such as: in the kitchen, falconry, mint, textile workshops, the administration or the royal guard (in the case of harem guards, they were castrated), but female saqaliba were placed in the harem.[104]

The harem could contain thousands of slave concubines; the harem of Abd al-Rahman I consisted of 6,300 women.[105] The saqaliba concubines were appreciated for their light skin.[106] The concubines (jawaris) were educated in accomplishments to make them attractive and useful for their master, and many became known and respected for their knowledge in a variety of subjects from music to medicine.[106] A jawaris concubine who gave birth to a child attained the status of an umm walad, and a favorite concubine was given great luxury and honorary titles such as in the case of Marjan, who gave birth to al-Hakam II, the heir of Abd al-Rahman III; he called her al-sayyida al-kubra (great lady).[107] Several concubines were known to have had great influence through their masters or their sons, notably Subh during the Caliphate of Cordoba, and Isabel de Solís during the Emirate of Granada.

However, concubines were always slaves subjected the will of their master. Caliph Abd al-Rahman III is known to have executed two concubines for reciting what he saw as inappropriate verses, and tortured another concubine with a burning candle in her face while she was held by two eunuchs after she refused sexual intercourse.[108] The concubines of Abu Marwan al-Tubni (d. 1065) were reportedly so badly treated that they conspired to murder him; women of the harem were also known to have been subjected to rape when rivaling factions conquered different palaces.[108]

The rulers of the Nasrid dynasty of the Emirate of Granada (1232–1492) customarily married their cousins, but also kept slave concubines in accordance with Islamic custom. The identity of these concubines is unknown, but they were originally Christian women (rūmiyyas) bought or captured in expeditions in the Christian states of Northern Spain, and given a new name when they entered the royal harem.[109]

Islamic Egypt

[edit]

The consorts of the Caliphs of the Fatimid Caliphate (909-1171) were originally slave-girls whom the Caliph either married or used as concubines (sex slaves).[110] The concubines in the Fatimid harem were in most cases of Christian origin, described as beautiful singers, dancers and musicians; they were often the subject of love poems, but also frequently accused of manipulating the Caliph.[111]

The consorts of the Sultans of the Bahri dynasty (1250–1382) were originally slave girls. The female slaves were supplied to the Bahri harem by the slave trade as children; they could be trained to perform as singers and dancers in the harem, and some were selected to serve as concubines (sex slaves) of the Sultan, who in some cases chose to marry them.[112]

During the Burji dynasty (1382–1517) the ruler of the Mamluk Sultanate often married free Muslim women of the Mamluk nobility. However, the Burji harem, as its predecessor, maintained the custom of slave concubinage, with Circassian slave girls being popular as concubines in the Burji harem.[113] Sultan Qaitbay (r. 1468–1496) had a favorite Circassian slave concubine, Aṣalbāy, who became the mother of Sultan Al-Nasir Muhammad (r. 1496–1498) and later married Sultan Al-Ashraf Janbalat (r. 1500–1501).[113] Her daughter-in-law, Miṣirbāy (d. 1522), a former Circassian slave concubine, married in succession Sultan Al-Nasir Muhammad (r. 1496–1498), sultan Abu Sa'id Qansuh (r. 1498–1500), and in 1517 the Ottoman Governor Khā’ir Bek.[113]

The Mamluk governor of Baghdad, Umar Pasha, died childless because his wife prevented him from having a concubine.[50] Writing in the early 18th century, one visitor noted that from among the Ottoman courtiers, only the imperial treasurer kept female slaves for sex and others thought of him as a lustful person.[114]

Edward Lane, who visited Egypt in the 1830s, noted that very few Egyptian men were polygamous and most of the men with only one wife did not keep concubines, usually for the sake of domestic peace. However, some kept Abyssinian slaves who were less costly than maintaining a wife. While white slave-girls would be in the keep of wealthy Turks, the concubines kept by upper and middle class Egyptians were usually Abyssinians.[115]

The harem of the Muhammad Ali dynasty of the Khedivate of Egypt (1805–1914) was modelled after Ottoman example, the khedives being the Egyptian viceroys of the Ottoman sultans. Muhammad Ali was appointed vice roy of Egypt in 1805, and by Imperial Ottoman example assembled a harem of slave concubines in the Palace Citadel of Cairo.[116]

Similar to the Ottoman Imperial harem, the harem of the khedive was modelled on a system of polygyny based on slave concubinage, in which each wife or concubine was limited to having one son.[117] The women harem slaves mostly came from Caucasus via the Circassian slave trade and were referred to as "white".[118] A minority of the slave women were selected to become the personal servants (concubines) of the khedive, often selected by his mother:[119] they could become his wives, and would become free as an umm walad (or mustawlada) if they had children with their enslaver.[120] However, the majority of the slave women served as domestics to his mother and wives.[121] The enslaved female servants of the khedivate harem were manumitted and married off with a trosseau in strategic marriages to the male freedmen or slaves (kul or mamluk) who were trained to become officers and civil servants as freedmen, in order to ensure the fidelity of their husband's to the khedive when they began their military or state official career.[122] The Egyptian elite of bureaucrat families, who emulated the khedive, had similar harem customs, and it was noted that it was common for Egyptian upper-class families to have slave women in their harem, which they manumitted to marry off to male protegees.[122]

Ottoman Empire

[edit]

The Ottoman rulers would keep hundreds, even thousands, of concubines in the Imperial harem. Most slaves in the Ottoman harem comprised women who had been kidnapped from Christian lands via the Barbary slave trade or the Crimean slave trade. Some had been abducted during raids by the Tatars while others had been captured by maritime pirates.[125] Female war captives were often turned into concubines for the Ottoman rulers. Ambitious slave families associated with the palace would also frequently offer their daughters up as concubines.[126] The most highly desired slave-concubines in the Muslim world were not African women, but white girls, typically of Circassian or Georgian origin. However, they were very expensive.[127] Both Circassian and Georgian women were systematically trafficked to eastern harems. This practice lasted into the 1890s.[126][128] Fynes Moryson noted that some Muslim men would keep their wives in various cities while others would keep them in a single house and would keep adding as many women as their lusts permitted. He wrote that "They buy free women to be their wives, or they buy 'conquered women' at a lesser price to be their concubines."[129] Ottoman society had provided avenues for men who wished to have extramarital sex. They could either marry more wives while wealthy men could possess slaves and use them for sex.[130]

Since the late 1300s Ottoman sultans would only permit heirs born from concubines to inherit their throne. Each concubine was only permitted to have one son. Once a concubine would bear a son she would spend the rest of her life plotting in favour of her son. If her son was to successfully become the next Sultan, she would become an unquestionable ruler. After the 1450s the Sultans stopped marrying altogether. Because of this there was great surprise when Sultan Sulayman fell in love with his concubine and married her. An Ottoman Sultan would have sexual relationships with only some women from his large collection of slave girls. This meant that a lot of the concubines were not given a family life if they were not desired by the Sultan. This effectively meant these women would have to spend the rest of their lives in virtual imprisonment. Some of these women would break the sharia by having homosexual relations.[92]

Research into Ottoman records show that polygamy was absent or rare in the 16th and 17th centuries.[131] Concubinage and polygamy were quite uncommon outside the elite. Goitein says that monogamy was a feature of the "progressive middle class" Muslims.[132] In Sudan "By the Turco-Egyptian period, slave-owners represented a broad range of the socio-economic spectrum, and slave-owning was no longer a confine of the rich. A man of average wealth may have enjoyed the comfort that a few slaves brought, but would not have had a harem of the type mentioned above. Instead, in this context, the slave woman who baked the bread or looked after the children also may have received the master's sexual advances. Thus the average slave woman probably played a double role as labourer and concubine."[133] Elite men were required to leave their wives and concubines if they wished to marry an Ottoman princess.[114] Enslaved European men also narrated accounts of women who "apostasised". The life stories of these women were similar to Roxelana, who rose from being a Christian slave-girl into the chief advisor of her husband, Sultan Suleyman of the Ottoman Empire. There are several accounts of such women of humble birth who associated with powerful Muslim men. While the associations were initially forced, the captivity gave women a taste for access to power. Diplomats wrote with disappointment about apostate women who wielded political influence over their masters-turned-husbands. Christian male slaves also recorded the presence of authoritative convert women in Muslim families. Christian women who converted to Islam and then became politically assertive and tyrannical were regarded by Europeans as traitors to the faith.[134]

Enslavement as a tool of the state

[edit]In the Ottoman Empire, repudiating the contract of dhimmah could always result in enslavement or other consequences. Rebellion was seen as the ultimate form of repudiating the contract. If non-Muslim subjects broke their contract with the Islamic state they were punished by enslavement but only with the approval of the state and in turn from the sharia.[135] This practice occurred frequently in the Balkans where local Christian groups from the late 17th century onwards sided with the Austrians and Russians. This resulted in slave-taking on an ongoing basis that further alienated Christian populations.[136] During the Greek Revolt, the Ottoman Empire enslaved former dhimmis. Local communities were dealt on a case-by-case basis, only those sections who had broken the contract were enslaved. The rest would not be affected as long as they retained their status as dhimmis. Rebels who had been pardoned by the state could also not be legally enslaved.[135]

The kadi of Ruscuk acknowledged receiving a general order in May 1821 that the enslavement of the wives and children of Greek rebels was legal because their crime had been treason. A hukum issued to the authorities in Izmir and Kusadasi endorsed the enslavement of the former dhimmis of Samos because they had rebelled and killed Muslims on the island.[135] A Maliki scholar in late-19th-century Cairo ruled that it was legitimate to enslave or kill the Jews and Christians who broke their pacts with Muslims,[137] but Ebussuud Efendi disagreed with the enslavement of certain dhimmis such as those who committed robbery or defaulted on their taxes.[135]

During the Armenian genocide, which climaxed around 1915–16, numerous Armenian women were raped and subjected to sexual slavery, with women forced into prostitution or forcibly married to non-Armenians,[138] or sold as sex slaves to military officials.[139] International reports at the time testified to the imprisonment of Armenian women as sex slaves and the complicity of the authorities in the setting up of slave markets and sale of Armenians.[140]

Barbary Coast

[edit]During Barbary pirate raids, Muslims enslaved an estimated 50–75,000 Christian women from Europe. Muslims took the slaves of non-Muslims when they won in battle.[102][134] Many such women were consigned to household service, with some European concubines achieved significant political power through their masters. For example, one 17th-century British diplomat reported that a European concubine had become the de facto ruler of the city state of Algiers.[134][vague] This refer to Mohammed Trik, the Dey of Algiers, who in an English report from 1676 is noted to have been married to his former slave concubine, described as a "cunning covetous English woman, who would sell her soule for a Bribe", with whom the English viewed it as "chargeable to bee kept in her favour... for Countrysake".[141]

European accounts typically condemned European concubines who converted to Islam as apostates, while praising women who bravely resisted the "depravity" of their Muslim masters.[134] This kind of writing would later give rise to the "harem fantasy" in 19th-century orientalism.[134] French general Thomas Robert Bugeaud wrote that children of concubines in Algeria were treated the same as other children and slaves enjoyed the same lifestyle as their owners.[142]

In Morocco, most slaves were black,[citation needed] and the 19th-century American journalist Stephen Bonsal remarked that high ranking Moroccan officials were sons of black concubines.[citation needed] Most Moroccan men remained monogamous as it was too expensive to have a concubine (or second wife),[143] while wealthy Moroccan men took concubines, and the sultans had large harems.[citation needed]

Zanzibar

[edit]Richard Francis Burton wrote "Public prostitutes are here few, and the profession ranks low where the classes upon which it depends can always afford to gratify their propensities in the slave-market."[144] Abdul Sheriff writes that the foregoing suggests "the easy availability of slave secondary wives affected even the oldest profession."[145]

The Islamic Law formally prohibited prostitution. However, since Islamic Law allowed a man to have sexual intercourse with his female slave, prostitution was practiced by a pimp selling his female slave on the slave market to a client, who returned his ownership of her after 1–2 days on the pretext of discontent after having had intercourse with her, which was a legal and accepted method for prostitution in the Islamic world.[146]

In 1844 the British Consul noted that there were 400 free Arab women and 800 men in Zanzibar, and the British noted that while prostitutes were almost nonexistent, men bought "secondary wives" (slave concubines) on the slave market for sexual satisfaction; "public prostitutes are few, and the profession ranks low where the classes upon which it depends can easily afford to gratify their propensities in the slave market",[147] and the US Consul Richard Waters commented in 1837 that the Arab men in Zanzibar "commit adultery and fornication by keep three or four and sometimes six and eight concubines".[148] Sultan Seyyid Said replied to the British Consul that the custom was necessary, because "Arabs won't work; they must have slaves and concubines".[149]

The concubines of the Royal harem of Zanzibar were referred to as sarari or suria, and could be of several different ethnicities, often Ethiopian or Circassian.[150] Ethiopian, Indian or Circassian (white) women were much more expensive than the majority of African women sold in the slave market in Zanzibar, and white women in particular were so expensive that they were in practice almost reserved for the royal harem.[151] White slave women were called jariyeh bayza and imported to Oman and Zanzibar via Persia (Iran) and it was said that a white slave girl "soon renders the house of a moderately rich man unendurable".[152] The white slave women were generally referred to as "Circassian", but this was a general term and did not specifically refer to Circassian ethnicity as such but could refer to any white women, such as Georgian or Bulgarian.[153] Emily Ruete referred to all white women in the royal harem as "Circassian" as a general term, one of whom was her own mother Jilfidan, who had arrived via the Circassian slave trade to become a concubine at the royal harem as a child.[154] When the sultan Said bin Sultan died in 1856, he had 75 enslaved sararai-concubines in his harem.[155]

Practice in Asia

[edit]Delhi Sultanate

[edit]The Muslim Sultanates in India before the Mughal Empire captured large numbers of non-Muslims from the Deccan. The children of Muslim masters and non-Muslim concubines would be raised as Muslims.[156] When Muslims would surround Rajput citadels, the Rajput women would commit jauhar (collective suicide) to save themselves from being dishonoured by their enemies. In 1296 approximately 16,000 women committed jauhar to save themselves from Alauddin Khalji's army.[157] Rajput women would commit it when they saw that defeat and enslavement was imminent for their people. In 1533 in Chittorgarh nearly 13,000 women and children killed themselves instead of being taken captive by Bahadur Shah's army.[158] For them rape was the worst form of humiliation. Rajputs practised jauhar mainly when their opponents were Muslims.[159]

Timurids

[edit]Historical records show that numerous royal Timurid concubines were not slaves, but free women from prestigious Muslim families.[160] The reason for that is men were only allowed a maximum of four wives,[161] so instead they would secure additional marital alliances through concubinage instead. Likewise 15th-century texts from the region advise princes to seek marital alliances through unions with noble women as opposed to with a female slave.[161] Taking free women as concubines was condemned by some contemporaries.[162]

Mughal Empire

[edit]

Under the Mughal Empire, the royalty and nobility kept concubines in addition to wives.[163] While concubines are often a feature of royal households, Mughal harems stood out for their elaborateness, size and pomp.[164] Francisco Pelseart describes that noblemen kept both wives and concubines, who lived in extravagant quarters.[165] Early Mughal harems were small, but Akbar had a harem of more than 5000 women and Aurangzeb's harem was even larger.[164] Mughals attempted to suppress slavery, with emperor Akbar forbidding enslavement of women and children in 1562, prohibiting slave trade, and freeing thousands of his own slaves.[166] However, Akbar wasn't always consistent and may have kept his own concubines.[166] After Akbar's death there was a return to older patterns, such as Jahangir taking the wives and daughters of a rebel into his harem and soldiers enslaving women from rebellious villages,[164] but the sale of slaves remained banned.[167] Ahmad Shah Abdali's army captured Maratha women to fill Afghan harems.[168] The Sikhs attacked Abdali and rescued 2,2000 Maratha girls.[169] Ovington, a voyager who wrote about his journey to Surat, stated that Muslim men had an "extraordinary liberty for women" and kept as many concubines as they could afford.[163] The nobles in India could possess as many concubines as they wanted.[170] Ismail Quli Khan, a Mughal noble, possessed 1200 girls. Another nobleman, Said, had many wives and concubines from whom he fathered 60 sons in just four years.[171]

Lower class Muslims were generally monogamous. Since they hardly had any rivals, women of the lower and middle class sections of society fared better than upper-class women who had to contend with their husbands' other wives, slave-girls and concubines.[172] A wife could enforce that her husband remain monogamous, by stipulating in the Islamic marriage contract that the husband was not allowed to take another wife or concubine. Such conditions were "commonplace" among middle-class Muslims in Surat in the 1650s.[173]

There is no evidence that concubinage was practiced in Kashmir where, unlike the rest of the medieval Muslim world, slavery was abhorred and not widespread. Except for the Sultans, there is no evidence that the Kashmiri nobility or merchants kept slaves.[174] In medieval Punjab the Muslim peasants, artisans, small tradesmen, shopkeepers, clerks and minor officials could not afford concubines or slaves,[175] but the Muslim nobility of medieval Punjab, such as the Khans and Maliks, kept concubines and slaves. Female slaves were used for concubinage in many wealthy Muslim households of Punjab.[176]

Colonial court cases from 19th-century Punjab show that the courts recognised the legitimate status of children born to Muslim zamindars (landlords) from their concubines.[177] The Muslim rulers of Indian princely states, such as the Nawab of Junagadh, also kept slave girls.[178] The Nawab of Bahawalpur, according to a Pakistani journalist, kept 390 concubines. He only had sex with most of them once.[179] Marathas captured during their wars with the Mughals had been given to the soldiers of the Mughal Army from the Baloch Bugti tribe. The descendants of these captives became known as "Mrattas" and their women were traditionally used as concubines by the Bugtis. They became equal citizens of Pakistan in 1947.[180]

Abolition in the Muslim World

[edit]While classical Islamic law permitted slavery, the abolition movement starting in the late 18th century in England and later in other Western countries influenced slavery in Muslim lands both in doctrine and in practice.[181] According to Smith "the majority of the faithful eventually accepted abolition as religiously legitimate and an Islamic consensus against slavery became dominant", though this continued to be disputed by some literalists.[182][183]

During the 20th century, the issue of chattel slavery was addressed and investigated globally by international bodies created by the League of Nations and the United Nations, such as the Temporary Slavery Commission in 1924–1926, the Committee of Experts on Slavery in 1932, and the Advisory Committee of Experts on Slavery in 1934–1939.[184] By the time of the UN Ad Hoc Committee on Slavery in 1950–1951, legal chattel slavery still existed only in the Arabian Peninsula: in Oman, in Qatar, in Saudi Arabia, in the Trucial States and in Yemen.[184] Legal chattel slavery was finally abolished in the Arabian Peninsula in the 1960s: Saudi Arabia and Yemen in 1962, in Dubai in 1963, and Oman as the last in 1970.[184]

The big royal harems in the Muslim world begun to dissolve in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, often due to either abolition or modernization of the Muslim monarchies, where the royal women where given a public role and no longer lived in seclusion. The Ottoman Imperial harem, the harem of the Muhammad Ali dynasty of Egypt, as well as the Qajar harem of Persia where all dissolved in the early 20th century. In other cases, the custom lasted longer. Chattel slavery, and thus the existence of secluded harem concubines, lasted longer in some Islamic states. The report of the Advisory Committee of Experts on Slavery (ACE) about Hadhramaut in Yemen in the 1930s described the existence of Chinese girls (Mui tsai) trafficked from Singapore for enslavement as concubines,[185] and the King and Imam of Yemen, Ahmad bin Yahya (r. 1948–1962), were reported to have had a harem of 100 slave women.[186] Sultan Said bin Taimur of Oman (r. 1932–1970) reportedly owned around 500 slaves, an estimated 150 of whom were women, who were kept at his palace at Salalah.[187]

In the 20th century, women and girls for the harem market in the Arabian Peninsula were kidnapped not only from Africa and Baluchistan, but also from the Trucial States, the Nusayriyah Mountains in Syria, and the Aden Protectorate.[188] In 1943, it was reported that girls lower in the Baluchi hierarchical nature were shipped via Oman to Mecca, where they were popular as concubines since Caucasian girls were no longer available, and were sold for $350–450.[189]They belonged to the lower social and economic classes. The dealers were mostly wealthy Baluchs from Makran, Jask, Bahu and Dashtiyari.[190][191] Harem concubines existed in Saudi Arabia until the very end of the abolition of slavery in Saudi Arabia in 1962. In August 1962, the king's son Prince Talal stated that he had decided to free his 32 slaves and fifty slave concubines.[192] After the abolition of slavery in Saudi Arabia in 1962, the Anti-Slavery International and the Friends World Committee expressed their appreciation over the emancipation edict of 1962, but did ask if any countries would be helped to find their own nationals in Saudi harems who might want to return home; this was a very sensitive issue, since there was an awareness that women were enslaved as concubines (sex slaves) in the seclusion of the harems, and that there were no information as to whether the abolition of slavery had affected them.[193]

Colonial governments and independent Muslim states restricted slave raids and the slave trade in response to pressure from Western liberals and nascent Muslim abolitionist movements. Eliminating slavery was an even more difficult task. Many Muslim governments had refused to sign the international treaties against slavery which the League of Nations was co-ordinating since 1926. This refusal was also an issue at the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights and at the 1956 Anti-Slavery Convention.[194] It was mostly because of the pressure from European colonial powers and economic changes that slavery was abolished. While the institution was eventually abolished, there was no internally well-developed Islamic narrative against slave-ownership.[27]

In the 1830s, a group of ulama led by Waji al-Din Saharanpuri issued a fatwa that it was lawful to enslave even those men and women "who sought refuge" after battle. Sayyed Imdad Ali Akbarabadi led ulama in publishing a lot of material in defence of traditional kinds of slavery. Sayyid Muhammad Askari condemned the idea of abolishing slavery.[195] In the 19th century, some ulama in Cairo refused to allow slave girls, who had been freed under secular law, to marry unless they had obtained permission from their owner. After 1882 the Egyptian ulama refused to prohibit slavery on the grounds that the Prophet had never forbidden it. In 1899 a scholar from Al-Azhar, Shaykh Muhammad Ahmad al-Bulayqi implicitly defended concubinage and refuted modernist arguments.[196] Most ulama in West Africa opposed abolition. They ruled that concubinage was still allowed with women of slave descent.[197]

Female slavery, being a condition necessary to the legality of this coveted indulgence [concubinage], will never be put down, with a willing or hearty co-operation by any Mussalman community.

William Muir, Life of Mahomet.[198]

Ehud R. Toledano states that abolitionist views were very rare in Muslim societies and that there was no indigenous abolitionist narrative in the Muslim world. According to Toledano, the first anti-slavery views came from Syed Ahmad Khan in the subcontinent. The next anti-slavery texts are to be found, from the 1920s onwards, in the works of non-ulema who were writing outside the realm of Islamic tradition and Shariah. According to Amal Ghazal, the abolitionist stances of modernist ulema in Egypt such as Muhammad 'Abduh and his disciples were strongly opposed by the majority of Islamic jurists. While 'Abduh took a stand in favour of abolition, he noted that only a gradualist approach, which encouraged manumission, would work because slavery itself was sanctioned in Islamic law.[199]

While in the late 19th century some Indian Muslim modernists had rejected the legitimacy of slavery in Islam, a reformist take on slavery was a part of regenerated Indian Muslim thinking in the 1860s and 1870s.[200] Syed Ahmad Khan and Syed Ameer Ali were primarily concerned with refuting Western criticism of Islamic slavery. However, they did not directly refute the European criticism about female slavery and concubinage.[201] According to Dilawar Husain Ahmad, polygamy and concubinage were responsible for "Muslim decline".[202] Chiragh Ali denied the Qur'anic permission for concubinage. However, he accepted William Muir's view that Muslims would not abandon female slavery willingly, but he asserted that Islamic jurists did not allow concubinage with the female slaves being imported from Africa, Central Asia and Georgia in that time. However, he did not specify who these Islamic jurists were.[198] Syed Ahmad Khan was opposed by the ulama on a number of issues, including his views on slavery.[202]

In 1911 one Qadi in Mombasa ruled that no government can free a slave without the owner's permission. Spencer Trimingham observed that in coastal Arab areas masters continued to take concubines from slave families because the descendants of slaves are still considered to be enslaved under religious law even if they had been freed according to secular law.[197] The Ottoman ulama maintained the permissibility of slavery due to its Islamic legal sanction. They rejected demands by Young Ottomans for fatwas to ban slavery.[196]

In Pakistan, where the Deobandi Islamic revivalist movement is prevalent, the ulama called for the revival of slavery in 1947. The wish to enslave enemies and take concubines was noted in the Munir Commission Report. When Zia ul Haq came to power in 1977 and started applying sharia, some argued that the reward for freeing slaves meant that slavery should not be abolished "since to do so would be to deny future generations the opportunity to commit the virtuous deed of freeing slaves."[203] Similarly, many ulama in Mauritania did not recognise the legitimacy of abolishing slavery. In 1981 a group of ulama argued that only owners could free their slaves and that the Mauritanian government was breaking a fundamental religious rule. In 1997 one Mauritanian scholar stated that abolition[197]

... is contrary to the teachings of the fundamental text of Islamic law, the Koran... [and] amounts to the expropriation from Muslims of their goods, goods that were acquired legally. The state, if it is Islamic, does not have the right to seize my house, my wife or my slave.

The translator of Ibn Kathir's treatise on slaves, Umar ibn Sulayman Hafyan, felt obliged to explain why he published a slave treatise when slavery no longer exists. He states that just because slavery no longer exists does not mean that the laws about slavery have been abrogated. Moreover, slavery was only abolished half a century ago and could return in the future. His comments were a reflection of the predicament modern Muslims find themselves in.[204]

Modern Muslim perspectives

[edit]Today, most ordinary Muslims ignore the existence of slavery and concubinage in Islamic history and texts. Most also ignore the millennia-old consensus permitting it and a few writers even claim that those Islamic jurists who allowed sexual relations outside marriage with female slaves were mistaken.[205] Ahmed Hassan, a 20th-century translator of Sahih Muslim, who prefaced the translated chapter on marriage by claiming that Islam only allows sex within marriage. This was despite the fact that the same chapter included many references to Muslim men having sex with slave-girls.[205] Muhammad Asad also rejected the notion of any sexual relationship outside of marriage.[206] Ali notes that one reason for this defensive attitude may lie with the desire to argue against the common Western media portrayal of "Islam as uniquely oppressive toward women" and "Muslim men as lascivious and wanton toward sexually controlled females".[205]

Asifa Quraishi-Landes observes that most Muslims believe that sex is only permissible within marriage and they ignore the permission for keeping concubines in Islamic jurisprudence.[207] Furthermore, the majority of modern Muslims are not aware that Islamic jurists had made an analogy between the marriage contract and sale of concubines and many modern Muslims would be offended by the idea that a husband owns his wife's private parts under Islamic law. She notes that "Muslims around the world nevertheless speak of marriage in terms of reciprocal and complementary rights and duties, mutual consent, and with respect for women's agency" and "many point to Muslim scripture and classical literature to support these ideals of mutuality — and there is significant material to work with. But formalizing these attitudes in enforceable rules is much more difficult."[207] She personally concludes that she is "not convinced that sex with one's slave is approved by the Quran in the first place", claiming that reading the respective Quranic section has led her to "different conclusions than that held by the majority of classical Muslim jurists."[62] She agrees "with Kecia Ali that the slavery framework and its resulting doctrine are not dictated by scripture".[208]

Cognitive scientist Steven Pinker noted in The Better Angels of Our Nature that despite the de jure abolitions of slavery by Islamic countries in the 20th century,[209] the majority of the countries where human trafficking still occurs are Muslim-majority,[210] while political scientists Valerie M. Hudson and Bradley Thayer have noted that Islam is the only major religious tradition that still allows polygyny.[211]

Modern parallels

[edit]Since slavery existed in some states of the Muslim world until the mid-20th century, concubinage existed in some Muslim countries as late as the 1960s. For instance, a large number of women lower in the Baluch hierarchical nature (Afro-Baluchs[212][213] and low class Baluchs)[214] were kidnapped in the first half of the 20th century by slave traders and sold for sex across the Persian Gulf in settlements such as Sharjah, [215] where slavery in the Trucial States was legal until 1963.[216]

After the abolition of slavery in Muslim countries in the 19th and 20th centuries, however, there have been a number of examples of the revival of concubinage or slavery-like practices in the Muslim world.

During the partition of India, some of the violence against women resembled concubinage with religious undertones,[217] with some women being kept captives as forced wives and concubines.[218][219] According to some accounts, non-Muslim women captured by the Pakistan Army would be forcibly converted to Islam to be "worthy" of their captors' harems.[217] In Kashmir, Pashtun tribesmen allegedly captured a large number of non-Muslim girls from Kashmir and sold them as slave-girls in West Punjab.[220] The violence was paralleled on both sides of the conflict, with Muslim girls in East Punjab also being taken by and distributed among the Sikh jathas, Indian military and police for sex and sold on multiple times.[221] The governments of India and Pakistan later agreed to restore Hindu and Sikh women to India and Muslim women to Pakistan.[222]

In Afghanistan, reportedly one of the atrocities committed by the Taliban was the enslavement of women for use as concubines.[27][223] In 1998, eyewitnesses in Afghanistan reported that hundreds of girls in Kabul and elsewhere had been abducted by Taliban fighters.[224] One source suggests that up to 400 women were involved in the abductions across Afghanistan. However the Taliban vehemently denied all these claims as propaganda against them by their enemies in Afghanistan.[225]

During the 1983-2005 Second Sudanese Civil War, the Sudanese army also revived the use of enslavement as a weapon against the South,[226] particularly against black Christian prisoners of war,[227] on the purported basis that Islamic law allowed it.[27] In raids by Janjaweed militias on black Christian villages, thousands of women and children were taken captive,[228] with some (Dinka girls) kept in Northern Sudanese households for use as sex slaves,[229] while others sold in slave markets as far afield as Libya.[227]

In the 21st century, when ISIL fighters attacked the city of Sinjar in 2014, they kidnapped and raped local women.[230] ISIL's extremist agenda extended to women's bodies and that women living under their control, with fighters being told that they were theologically sanctioned to have sex with non-Muslim captive women.[231]

Muslim community response

[edit]The justifications for modern reiterations of slavery and violence against women, most notably in the context of ISIL, have been vocally condemned by Islamic scholars from around the world at the time.[232][233][234]

In response to the Nigerian extremist group Boko Haram's Quranic justification for kidnapping and enslaving people,[235][236] and ISIL's religious justification for enslaving Yazidi women as spoils of war as claimed in their digital magazine Dabiq,[237][238][239] 126 Islamic scholars from around the Muslim world signed an open letter in September 2014 to the Islamic State's leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi decrying his group's interpretations of the Qur'an and hadith.[240][241] The letter also accused the group of committing sedition by re-instituting slavery under its rule in contravention of the anti-slavery consensus of the Islamic scholarly community.[242]

In popular culture

[edit]- Magnificent Century, Turkish TV series about the Ottoman Harem and Hürrem Sultan

- Muhteşem Yüzyıl: Kösem, Turkish TV series about the Ottoman Harem and Kösem Sultan

- Hayriye Melek Hunç was the first female author of Circassian descent. Melek wrote an essay "Dertlerimizden: Beylik-Kölelik" (One of our troubles: Seigniory-Slavery) to encourage Ottoman palace to do away with slavery. Through her story "Altun Zincir" (Golden Chain) Melek narrates the story of sorrow of Caucasian concubines of the harem for missing their Caucasus homeland and pointed out that in spite of elite life opportunities for some of these concubines, at the end of the day they remain slaves and their existence as a woman gets ruined.[243][244]

- Leyla Achba was the first Ottoman court lady who wrote memoirs. Book name: "Bir Çerkes Prensesinin Harem Hatıratı. " (Harem Memoirs of a Circassian Princess).

- Rumeysa Aredba was a lady-in-waiting to Nazikeda Kadın, wife of Mehmed VI, the last Sultan of the Ottoman Empire. She is known for writing memoirs, which give details of the exile, and personality of Sultan Mehmed at San Remo. Book name: "Sultan Vahdeddin'in San Remo Günleri." (San Remo Days of Sultan Vahdeddin).

- Leyla Saz was a poet in the Ottoman Harem. She wrote her memories in the book "Haremde Yaşam - Saray ve Harem Hatıraları." (Life in the Harem - Memories of the Palace and Harem).

- Melek Hanım, as the wife of Mehmed Pasha of Cyprus, Melek Hanım is perhaps the first Ottoman woman to write her memoirs. Book name: Haremden Mahrem Hatıralar-Melek Hanım (Private Memories from the Harem-Melek Hanım).

- DOMENİCO'S İSTANBUL, memories of Domenico Herosolimitano, Ottoman court physician to Sultan Murad III.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ 'The study of the ancient Near East, the modern Middle East from Iran to Turkey to Egypt, has been pursued in the last two centuries in societies of Europe and the Americas that have themselves been mired in industrial slavery. Scholars of the ancient region have consequently been quick to point out that nowhere do we see the kind of mass exploitation that we find since the sixteenth century of our era..' (Snell 2011, p. 4)

- ^ 'Nowhere in the New Testament epistles does Paul or any other letter writer state explicitly that the sexual use of slaves constitutes sexual immorality or sexual impurity..the practice of using slaves as a benign and safe sexual outlet persisted throughout antiquity.' (Glancy 2002, pp. 49–51, 144)

- ^ Many societies in addition to those advocating Islam automatically freed the concubine, especially after she had had a child. About a third of all non-Islamic societies fall into this category.[citation needed]

- ^ 'Encouragement to manumit slaves, enshrined in the Qur'an and law, likely contributed to social mobility., Manumitting slaves earned their owner eternal rewards. The Qur'an advocated manumission of slaves as an act of a righteous person or as a religious boon...Key hadith also support manumission: "He who has a slave-girl and teaches her good manners and improves her education then manumits and marries her, will get a double reward." Concubines, however, sometimes had a surer route to manumission than their owners' desire for spiritual coinage; under certain conditions their wombs could provide escape from slavery. A slave who bore a child to a free man, known as an umm al-walad, could not be sold, in most circumstances, and at her owner's death, she was to be freed (Hain 2017, p. 328).

- ^ 'Other issues differentiating the classical doctrine and modernist approaches include the treatment of prisoners of war, with some of the early jurists allowing Muslim commanders a choice only between killing or enslaving them, and others – on the principle of serving the public interest (maṣlaḥa) –giving commanders more discretion to ransom prisoners (for example, in exchange for Muslim prisoners or for money) or even to release them unconditionally. Seizing on this principle of public interest, and pointing to the obsolescence of practices such as slavery, virtually all modernists by contrast narrow the options to those sanctioned by contemporary international norms: releasing prisoners upon the cessation of hostilities either unconditionally or as part of reciprocal exchanges.' (Mufti 2019, p. 5)

- ^ 'Female slaves around the Mediterranean were subject to sexual and reproductive demands as well as demands on their physical labour. Focusing on the sexual and reproductive aspects of the shared culture of Mediterranean slavery reveals three things. First, though historians have paid more attention to the sexual exploitation of slave women in Islamic contexts, sexual exploitation was also common and well documented in Christian contexts. Second, the most important difference between Islamic and Christian practices of slavery had to do with the status of children. Under Christian and Roman law, children inherited the status of their mothers, so the child of a free man and a slave woman would be a slave. In contrast, under Islamic law, if a free man acknowledged paternity of a child by his slave woman, that child was born free and legitimate.' (Barker 2019, p. 61)

- ^ 'With the transition from the Umayyads to the Abbasids, the upward swell of subaltern demographics thrust individual concubines unambiguously into the realm of elite politics. Whereas only the last three Umayyad caliphs were born to concubines, the great majority of the early Abbasid caliphs were sons of this heretofore nameless class of women.' (Hain 2017, p. 328,4,246)

- ^ The conquests, however, had consequences that ultimately upset the pre-Islamic system. As the Umayyad dynasty matured, certain families within the Quraysh became significantly wealthier and more powerful than tribes that had once been equal to them...In this new order, the Muslim elites turned to the cheapest, safest, and most loyal women available to them: cousins and concubines.[79]

Citations

[edit]- ^ "Harem Scene with Mothers and Daughters in Varying Costumes (1997.3.26)". Brooklyn Museum.

- ^ Peter N. Stearns (ed.). "Concubinage". Encyclopedia of Social History. p. 317.

The system in Muslim societies was an arrangement in which a slave woman lived with a man as his wife without being married to him in a civil or normal way.

- ^ Hain 2017, p. 326: "Concubines in Islamic society, with few exceptions, were slaves. Sex with your own property was not considered to be adultery (zina). Owners purchased the sexuality of the enslaved along with their bodies."

- ^ Hamid 2017, p. 190: "Timurid sources from the later period list numerous women as royal concubines who were not slaves."

- ^ Dalton Brock. "Concubines - Islamic Caliphate". In Colleen Boyett; H. Micheal Tarver; Mildred Diane Gleason (eds.). Daily Life of Women: An Encyclopedia from Ancient Times to the Present. ABC-CLIO. p. 70.

However, that did not deter wealthy households from also seeking and acquiring freewomen as concubines, although such a practice was argued to be in violation of sharia law.

- ^ Hamid 2017, p. 193: "The disregard for Muslim legal codes regulating marriage and concubinage did not go uncommented on by contemporaries. In his memoirs, Babur disapproved of the practice of taking free Muslim women as concubines [in the Tamurid dynasty], deeming the relationships to be unlawful."

- ^ Schacht, J. (2012-04-24), "Umm al-Walad", Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, Brill, retrieved 2023-09-17

- ^ Nirenberg 2014, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Yagur 2020, pp. 101–102.

- ^ Mufti 2019, pp. 1–6.

- ^ a b c Clarence-Smith 2006, p. 22.

- ^ Brandeis University.

- ^ Ali 2015a, p. 52: "the vast majority of Muslims do not consider slavery, especially slave concubinage, to be acceptable practices for the modern world"

- ^ Cortese 2013.

- ^ a b Rodriguez 2011, p. 203.

- ^ a b The International Encyclopedia of Anthropology 1999.

- ^ a b c Cortese & Calderini 2006

- ^ a b c d Myrne 2019, p. 203.

- ^ a b Klein 2014, p. 122

- ^ a b c d Katz 1986

- ^ Bloom & Blair 2002, p. 48.

- ^ Gordon & Hain 2017, p. 328.

- ^ Peirce 1993, p. 30.

- ^ Peirce 1993, p. 39.

- ^ Peirce 1993, p. 37–39.

- ^ Peirce 1993, p. 42-43.

- ^ a b c d e Ali 2015a, p. 53–54.

- ^ Badawi 2019, p. 17.

- ^ a b Clarence-Smith 2006, p. 27–28.

- ^ a b Bernard Lewis (1992). Race and Slavery in the Middle East: An Historical Enquiry. Oxford University Press. pp. 9–10.

- ^ McMahon 2013, p. 18.

- ^ Antunes, Trivellato & Halevi 2014, p. 57.

- ^ Willis 2014.

- ^ Erdem 1996, p. 52.

- ^ Mary Ann Fay. Unveiling the Harem: Elite Women and the Paradox of Seclusion in Eighteenth-Century Cairo. Syracuse University Press. p. 78.

Without war captives or a system of slave breeding, which did not exist in the Middle East, slaves would have to be imported from outside as they were from Caucasus and Africa.

- ^ Williams, Hettie V.; Adekunle, Julius O. (eds.). Color Struck: Essays on Race and Ethnicity in Global Perspective. University Press of America. p. 63.

Not only was slavery not racialized under Islamic rule nor was it hereditary...

- ^ Alan Mikhail (2020). God's Shadow: Sultan Selim, His Ottoman Empire, and the Making of the Modern World. p. 137.

In Islam, slavery was temporary, not hereditary

- ^ Ali 2015a, p. 57.

- ^ Gleave 2015, p. 166–168.

- ^ Clarence-Smith 2006, p. 43–44.

- ^ a b Myrne 2019, pp. 222–223.

- ^ Bellagamba, Greene & Klein 2016, p. 24.

- ^ Kamrava 2011, p. 193.

- ^ Abou El Fadl 2014, p. 198.

- ^ Abou El Fadl 2006, p. 198.

- ^ a b Myrne 2019, p. 218.

- ^ Khaled Abou El Fadl (1 October 2014). Speaking in God's Name: Islamic Law, Authority and Women. p. 525.

- ^ Amira Bennison. The Great Caliphs: The Golden Age of the 'Abbasid Empire. Yale University Press. pp. 146–147.

- ^ Afary 2009, p. 81–82.

- ^ a b Clarence-Smith 2006, p. 81.

- ^ Bouachrine 2014, p. 8.

- ^ Layish, p. 331.

- ^ a b Brown 2019, p. 70.

- ^ Robinson, p. 90.

- ^ Reda & Amin, p. 228.

- ^ a b Myrne 2019, pp. 196–197.

- ^ Ali 2015a, p. 50–51.

- ^ a b c Ali 2017.

- ^ Bowen 1928, p. 13.

- ^ a b "Umm al-Walad". Oxford Islamic Studies. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015.

- ^ Brockopp 2000, pp. 195–196.

- ^ a b Quraishi-Landes 2016, p. 178.

- ^ Azam 2015, p. 69.

- ^ Asy-Syafi'i R. A., Al-Imam (1989). Al-Umm = Kitab induk. Vol. 5. Kuala Lumpur: Victory Agencie. p. 203. ISBN 9789839581522.

- ^ Ali 2010, p. 119

- ^ Kecia Ali. "Muwatta Roundtable: The Handmaiden's Tale". Islamiclaw.blog.

Some offer whole theories about the need for enslaved women's and girls' consent to sex with their owners based on a decontextualized legal maxim or quotation—a purportedly pro-consent snippet from Shafiʿī has been making the rounds lately. (footnote 2) The phrase from the Umm is "فَأَمَّا الْجِمَاعُ فَمَوْضِعُ تَلَذُّذٍ وَلَا يُجْبَرُ أَحَدٌ عَلَيْهِ" ("However, intercourse is a matter of pleasure and no one is compelled to it"). ... However, this passage, understood in its context, doesn't speak to consent but rather asserts that men have no obligation to have sex equally with their wives.

- ^ Intisar, p. 152.

- ^ Sonn 2015, p. 18.

- ^ Ali 2017, p. 148.

- ^ Brown 2019, p. 282–283.

- ^ Brown 2019, p. 96.

- ^ Ali 2017, p. 149.

- ^ a b Ali 2017, p. 150.

- ^ Ali 2011, p. 76.

- ^ a b c d Friedmann 2003, pp. 107–108

- ^ Friedmann 2003, pp. 176–178.

- ^ Ali 2015a, p. 41.

- ^ Majied 2017, p. 16–17.

- ^ Majied 2017, pp. 20–21

- ^ a b Majied 2017, pp. 11–12

- ^ a b c Mubarakpuri 1998, pp. 259–264

- ^ Saron 1986, p. 266.

- ^ Faizer 2013, p. 462.

- ^ Ibn Rashid 2015, p. 68.

- ^ a b Faizer 2013, p. 466.

- ^ Ibn al-Athir 1998.

- ^ Al-Tabari 1990, p. 25.

- ^ a b Faizer 2013, p. 459.

- ^ Al-Tabari 1990, p. 26.

- ^ Robinson 2020, p. 107.

- ^ a b c Robinson 2020, p. 96–97.

- ^ a b c Clarence-Smith 2006, p. 89.

- ^ Lewis, B. (1990). Race and Slavery in the Middle East: An Historical Enquiry. Storbritannien: Oxford University Press. p. 40

- ^ Myrne 2019, p. 206.

- ^ The Cambridge World History of Slavery: Volume 2, AD 500-AD 1420. (2021). Storbritannien: Cambridge University Press. p. 197

- ^ The Cambridge World History of Slavery: Volume 2, AD 500-AD 1420. (2021). Storbritannien: Cambridge University Press. p. 198

- ^ The Cambridge World History of Slavery: Volume 2, AD 500-AD 1420. (2021). Storbritannien: Cambridge University Press. p. 199

- ^ Myrne, P. (2019). Slaves for Pleasure in Arabic Sex and Slave Purchase Manuals from the Tenth to the Twelfth Centuries. Journal of Global Slavery, 4(2), 196-225. https://doi.org/10.1163/2405836X-00402004

- ^ a b c Bennison 2016, p. 155–156.

- ^ Gleave 2015, p. 171.

- ^ Schaus 2006, p. 593.

- ^ a b Capern 2019, p. 22.

- ^ Salzmann 2013, p. 397.

- ^ Scales, Peter C. (1993). The Fall of the Caliphate of Córdoba: Berbers and Andalusis in Conflict. Brill. p. 66. ISBN 9789004098688.

- ^ Man, John (1999). Atlas of the Year 1000. Harvard University Press. p. 72. ISBN 9780674541870.

- ^ a b Ruiz, Ana (2007). Vibrant Andalusia: The Spice of Life in Southern Spain. Algora Publishing. p. 35. ISBN 9780875865416.

- ^ Barton, Simon (2015). Conquerors, Brides, and Concubines: Interfaith Relations and Social Power in Medieval Iberia. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 1. ISBN 9780812292114.