Plantation (settlement or colony)

In the history of colonialism, a plantation was a form of colonization in which settlers would establish permanent or semi-permanent colonial settlements in a new region. The term first appeared in the 1580s in the English language to describe the process of colonization before being also used to refer to a colony by the 1610s. By the 1710s, the word was also being used to describe large farms where cash crop goods were produced, typically in tropical regions.[1]

The first plantations were established during the Edwardian conquest of Wales and the plantations of Ireland by the English Crown. In Wales, King Edward I of England began a policy of constructing a chain of fortifications and castles in North Wales to control the native Welsh population; the Welsh were only permitted to enter the fortifications and castles unarmed during the day and were forbidden from trading.[2] In Ireland, during the Tudor and Stuart eras the English Crown initiated a large-scale colonization of Ireland, in particular the province of Ulster, with Protestant settlers from Great Britain. These plantations led to the demography of Ireland becoming permanently altered, creating a new Protestant Ascendancy which would dominate Irish society for the next few centuries.[3]

In North America, during the period of European colonization in the early modern period, several plantations were established by English settlers, including in Virginia, Rhode Island, and elsewhere throughout the Thirteen Colonies. Other European colonial powers used the plantation method of colonization as well, though not to the extent of English settlers.[4]

Europe

[edit]Wales

[edit]

Starting in the reign of King Edward I of England, the English Crown began a policy of castle building and settlement building in Wales to control the population, and strategically surround the newly conquered Kingdom of Gwynedd.[5]

Most of these castles were built with an integrated fortified town, which was designed to be provisioned from safer territories and hold out against Welsh attacks, an idea that the Normans had developed from the bastides of Gascony. These bastide towns were defended by stone fortifications some designed by James of St. George d'Esperanche. The towns were exclusively populated with English or Flemish settlers, who depended on the crown for their survival in Wales. The Welsh themselves were not permitted to enter the town after dark, held no rights to trade and were not allowed to carry arms.[6][7]

Today, the Iron Ring is a contentious part of Welsh history. In 2017, when plans were announced for an iron sculpture of a giant ring as part of a restoration project of Flint Castle, the project was met with criticism and accusations that it was commemorating the Edwardian conquest of Wales, a contentious event among the Welsh public.[8] The plans were ultimately cancelled after social media campaign and petition.[9]

Ireland

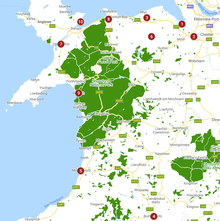

[edit]The Plantations of Ireland occurred in the 16th and 17th centuries and involved the English Crown confiscating lands owned by the Irish people, starting in the 1550s with Queen Mary I who was Catholic, with British Catholic settlers. Later plantations involved redistributing them to Protestant settlers from Great Britain. Though there had been periodic immigration from Great Britain to Ireland since the Anglo-Norman invasion, these immigrants had largely assimilated into Irish culture or were driven off from what little land they controlled by the 15th century, and the direct area controlled by the English Crown had shrunk mostly to an area known as the Pale.[10][11][12][13][14]

Beginning in the 1540's, the Tudor conquest of Ireland began, and roughly a decade later the first English plantations were established by British settlers on Irish soil. These plantations began during the reign of Queen Mary I of England in the counties of Laois and Offaly. However, these efforts at establishing plantations largely failed due to attacks from the local Irish clans.[15][16] The next wave of plantations began during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I of England and were spearheaded by the West Country Men. Elizabeth's policy in Ireland was to grant land to prospective planters and prevent the Irish from giving Spain a base from which to attack England.[17]

The plantation of Ulster began in the 1610s, during the reign of James I. Following their defeat in the Nine Years' War, many rebel Ulster lords fled Ireland and their lands were confiscated. This was the biggest and most successful of the plantations and comprised most of the province of Ulster. While the province was mainly Irish-speaking and Catholic, the new settlers were required to be English-speaking and Protestant, with most coming from England and Scotland. This created a distinct Ulster Protestant community.[18]

North America

[edit]

Beginning in the 15th century with the voyages of Christopher Columbus, various European colonial powers established colonies in the Americas.

The Portuguese introduced Sugar plantations in the Caribbean in the 1550s.

England's efforts at colonization primarily focused on North America, where the first English plantation was established in 1607 at Jamestown. Over the next century, more English plantations would be established along the Eastern Seaboard, which collectively came to be known as the Thirteen American Colonies, consisting of the New England, Middle and Southern colonies. Other European colonial powers used the plantation method of colonization as well, though not to the extent of English settlers.[19]

A typical example of a colonial plantation was Providence Plantations, the first permanent European settlement in Rhode Island.[20][21] Providence Plantations was established along the Providence River by Puritan minister Roger Williams and a small band of followers, who were fleeing religious persecution in Massachusetts Bay.[22] Upon arriving in Rhode Island, Williams and his followers received a land grant from two Narragansett sachems, Canonicus and Miantonomi.[23] The settlers in Providence Plantations adopted a covenant which stressed the separation of religious and civil affairs.[24]

That plantation was part a larger series of English plantations in New England. These plantations played a large role in developing the Northern economy in opposing lines from the plantation-based economy of the American South. Compared to the large-scale cash crop plantations which underpinned the Southern economy, plantations in New England were small-scale, and meant mainly for subsistence purposes rather than profit making.[25]

Sources

[edit]- Albert Galloway Keller, 1908, Colonization: A Study of the Founding of New Societies, Bastion: Ginn & Company

References

[edit]- ^ "Etymology of plantation". Online etymology dictionary. Online etymology dictionary. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ^ John Davies (1990). A History of Wales. Penguin Books. ISBN 9780140284751.

- ^ David Edwards, The Origins of Sectarianism in Early Modern Ireland, p. 116

- ^ James E. Seelye Jr.; Shawn Selby (2018). Shaping North America: From Exploration to the American Revolution [3 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. p. 344. ISBN 978-1-4408-3669-5.

- ^ John Davies (1990). A History of Wales. Penguin Books. ISBN 9780140284751.

- ^ Thomas, Jeffrey (2009). "Welsh Castles of Edward I". Castles of Wales. Retrieved October 20, 2019.

- ^ Beresford, Maurice Warwick (1967). New Towns of the Middle Ages: Town Plantation in England, Wales, and Gascony. Praeger.

- ^ "Flint iron ring sculpture plans met with criticism". BBC News. 24 July 2017.

- ^ "'Insulting' Flint Castle iron ring plans scrapped". BBC News. 7 September 2017.

- ^ Falkiner, Caesar Litton (1904). Illustrations of Irish history and topography, mainly of the 17th century. London: Longmans, Green, & Co. p. 117. ISBN 1-144-76601-X.

- ^ Moody, T. W.; Martin, F. X., eds. (1967). The Course of Irish History. Cork: Mercier Press. p. 370.

- ^ Ranelagh, John (1994). A Short History of Ireland. Cambridge University Press. p. 36.

- ^ Kearney, Hugh (2012). The British Isles: A History of Four Nations. Cambridge University Press. p. 117.

- ^ Ruth Dudley Edwards; Bridget Hourican (2005). An Atlas of Irish History. Psychology Press. pp. 33–34.

- ^ Tittler, Robert (1991). The Reign of Mary I. Second edition. London & New York: Longman. ISBN 0-582-06107-5.

- ^ Brady, Ciaran. The Chief Governors: The Rise and Fall of Reform Government in Tudor Ireland 1536-1588. Cambridge University Press, 2002. p.130

- ^ Somerset, Anne (2003), Elizabeth I (1st Anchor Books ed.), London: Anchor Books, ISBN 978-0-385-72157-8

- ^ Ellis, Steven (2014). The Making of the British Isles: The State of Britain and Ireland, 1450-1660. Routledge. p. 296.

- ^ Robert Neelly Bellah; Richard Madsen; William M. Sullivan; Ann Swidler; Steven M. Tipton (1985). Habits of the Heart: Individualism and Commitment in American Life. University of California Press. p. 220. ISBN 978-0-520-05388-5. OL 7708974M.

- ^ Mudge, Zachariah Atwell (1871). Foot-Prints of Roger Williams: A Biography, with Sketches of Important Events in Early New England History, with Which He Was Connected. Hitchocok & Waldon. Sunday-School Department. ISBN 1270833367.

- ^ Straus, Oscar Solomon (1936). Roger Williams: The Pioneer of Religious Liberty. Ayer Co Pub. ISBN 9780836955866.

- ^ Mattern, Joanne (2003). Rhode Island: The Ocean State. Gareth Stevens. pp. 8–11. ISBN 9780836851595. Retrieved May 3, 2018.

- ^ Moyer, Sandra M.; Worthington, Thomas A. (2014). Cranston revisited. Charleston, S.C.: Arcadia Pub. p. 7. ISBN 9781467120791. Retrieved May 5, 2018.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 22 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 512.

- ^ The Agricultural Revolution in New England. Percy W. Bidwell. The American Historical Review, Vol. 26, No. 4 (J ul., 1921), 683–702. http://people.brandeis.edu/~dkew/David/Bidwell-agriculture-1921.pdf.