Sensus divinitatis

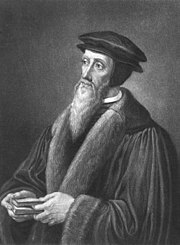

Sensus divinitatis (Latin for "sense of divinity"), also referred to as sensus deitatis ("sense of deity") or semen religionis ("seed of religion"), is a term first employed by French Protestant reformer John Calvin to describe a postulated human sense. Instead of knowledge of the environment (as with, for example, smell or sight), the sensus divinitatis is believed to give humans a knowledge of God.[1]

History

[edit]In Calvin's view, there is no reasonable non-belief:

That there exists in the human mind and indeed by natural instinct, some sense of Deity [sensus divinitatis], we hold to be beyond dispute, since God himself, to prevent any man from pretending ignorance, has endued all men with some idea of his Godhead…. …this is not a doctrine which is first learned at school, but one as to which every man is, from the womb, his own master; one which nature herself allows no individual to forget.[2]

Jonathan Edwards, the 18th-century American Calvinist preacher and theologian, claimed that while every human being has been granted the capacity to know God, a sense of divinity, successful use of these capacities requires an attitude of "true benevolence".[citation needed] Analytic philosopher Alvin Plantinga of the University of Notre Dame posits a similar modified form of the sensus divinitatis in his Reformed epistemology whereby all have the sense, only it does not work properly in some humans, due to sin's noetic effects.[3][page needed]

Roman Catholic theologian Karl Rahner proposed an innate sense or pre-apprehension of God, which has been noted to share elements in common with Calvin's Sensus Divinitatis.[4] This concept of innate knowledge of God is similar to the Islamic concept of Fitra.[citation needed]

Neo-Calvinists who adhere to the presuppositionalist school of Christian apologetics sometimes appeal to a sensus divinitatis to argue that there are no genuine atheists.[citation needed]

Science

[edit]Research in the cognitive science of religion suggests that the human brain has a natural and evolutionary predisposition towards theistic beliefs, which Kelly James Clark argues is empirical evidence for the presence of a sensus divinitatis.[5]

Criticism

[edit]Philosopher Evan Fales presents three arguments against the presence of a sensus divinitatis:[6]

- The divergence of claims and beliefs (lack of reliability, even within Christian sects).

- The lack of demonstrably superior morality of Christians versus non-Christians.

- Bible verses, accepted by most Christians as authored by men inspired by the Holy Spirit—presumably with a functioning sensus divinitatis—in which "God performs, commands, accepts or countenances rape, genocide, human sacrifice, pestilence to punish David for taking a census, killing David's infant to punish him, hatred of family, capital punishment for breaking a monetary promise, and so on".

Philosopher Steven Maitzen claimed in 2006 that the demographics of religious belief make the existence of the sensus divinitatis unlikely, as this sense appears so unevenly distributed.[7] However, Maitzen may[according to whom?] have confused Aquinas's sensus dei[citation needed] with sensus divinitatis—sensus divinitatis (a religious sense) only necessitates a core religious/faith component to one's beliefs, whereas the sensus dei aims at a natural knowledge of God—compare In the Twilight of Western Thought by Herman Dooyeweerd (1894–1977).[8]

Hans Van Eyghen further argues that the phenomenological description of the sensus divinitatis does not match what the cognitive sciences show about religious belief.[9]

References

[edit]- ^ Helm, Paul (1998). "John Calvin, the Sensus Divinitatis, and the noetic effects of sin". International Journal for Philosophy of Religion. 43 (2): 87–107. doi:10.1023/A:1003174629151. S2CID 169082078.

- ^ Calvin, John (1960). Institutes of the Christian Religion. US: Westminster/John Knox Press. ISBN 0-664-22028-2.

- ^ Plantinga, Alvin (2000). Warranted Christian Belief. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-513192-4.

- ^ Sire, James W (2014). Echoes of a Voice. Oregon: Cascade. p. 55. ISBN 9781625644152.

- ^ Stewart, Melville Y. (2010). Science and Religion in Dialogue. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 9781405189217.

- ^ Fales, Evan (2003-05-13). "Critical Discussion of Alvin Plantinga's Warranted Christian Belief". Noûs. 37 (2). Wiley Periodicals, Inc: 353–370. doi:10.1111/1468-0068.00443.

- ^ Maitzen, Steven (2006). "Divine hiddenness and the demographics of theism" (PDF). Religious Studies. 42 (2). Cambridge University Press: 177–91. doi:10.1017/S0034412506008274. Retrieved 2012-01-26.

- ^ Dooyeweerd, Herman (1960). In the Twilight of Western Thought. Paideia Press, Ltd (published 2012). p. 24. ISBN 978-0-88815217-6. Retrieved 2013-10-24.

- ^ Van Eyghen, Hans (2016). "There is no Sensus Divinitatis". Journal for the Study of Religions and Ideologies: 24–40.