Sensibility

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (May 2016) |

Sensibility refers to an acute perception of or responsiveness toward something, such as the emotions of another. This concept emerged in eighteenth-century Britain, and was closely associated with studies of sense perception as the means through which knowledge is gathered. It also became associated with sentimental moral philosophy.

Origins

[edit]One of the first of such texts would be John Locke's Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1690), where he says, "I conceive that Ideas in the Understanding, are coeval with Sensation; which is such an Impression or Motion, made in some part of the body, as makes it be taken notice of in the Understanding."[2] George Cheyne and other medical writers wrote of "The English Malady," also called "hysteria" in women or "hypochondria" in men, a condition with symptoms that closely resemble the modern diagnosis of clinical depression. Cheyne considered this malady to be the result of over-taxed nerves. At the same time, theorists asserted that individuals who had ultra-sensitive nerves would have keener senses, and thus be more aware of beauty and moral truth. Thus, while it was considered a physical and/or emotional fragility, sensibility was also widely perceived as a virtue.

In literature

[edit]Originating in philosophical and scientific writings, sensibility became an English-language literary movement, particularly in the then-new genre of the novel. Such works, called sentimental novels, featured individuals who were prone to sensibility, often weeping, fainting, feeling weak, or having fits in reaction to an emotionally moving experience. If one were especially sensible, one might react this way to scenes or objects that appear insignificant to others. This reactivity was considered an indication of a sensible person's ability to perceive something intellectually or emotionally stirring in the world around them. However, the popular sentimental genre soon met with a strong backlash, as anti-sensibility readers and writers contended that such extreme behavior was mere histrionics, and such an emphasis on one's own feelings and reactions a sign of narcissism. Samuel Johnson, in his portrait of Miss Gentle, articulated this criticism:

She daily exercises her benevolence by pitying every misfortune that happens to every family within her circle of notice; she is in hourly terrors lest one should catch cold in the rain, and another be frighted by the high wind. Her charity she shews by lamenting that so many poor wretches should languish in the streets, and by wondering what the great can think on that they do so little good with such large estates.[3]

Criticism

[edit]Objections to sensibility emerged on other fronts. For one, some conservative thinkers believed in a priori concepts, that is, knowledge that exists independent of experience, such as innate knowledge believed to be imparted by God. Theorists of the a priori distrusted sensibility because of its over-reliance on experience for knowledge. Also, in the last decades of the eighteenth century, anti-sensibility thinkers often associated the emotional volatility of sensibility with the exuberant violence of the French Revolution, and in response to fears of a revolution emerging in Britain, sensible figures were coded as anti-patriotic or even politically subversive. Maria Edgeworth's 1806 novel Leonora, for example, depicts the "sensible" Olivia as a villainess who contrives her passions or at least bends them to suit her selfish wants; the text also makes a point to say that Olivia has lived in France and thus adopted "French" manners. Jane Austen's 1811 novel Sense and Sensibility provides a more familiar example of this reaction against the excesses of feeling, especially those associated with women. Readers and many critics have seen the novel as a critique of the "cult" of sentimentalism prevalent in the late eighteenth century.[4]

The effusive nature of many sentimental heroes, such as Harley in Henry Mackenzie's 1771 novel The Man of Feeling, was often decried by contemporary critics as celebrating a weak, effeminate character, which ultimately contributed to a discrediting of previously popular sentimental novels (and to a lesser extent, all novels) as unmanly works. This concern coincided with a marked rise in the production of novels by women writers of the period, whether they chose to write in a sentimental mode or not, and played a significant role in larger debates about gender, genre, literary value, and nationalist political aims during the last decade of the eighteenth century and the first decades of the nineteenth, when the "National Tale" concept emerged in the wake of the French Revolutionary Wars and the union of Great Britain and Ireland.[5][6]

See also

[edit]References

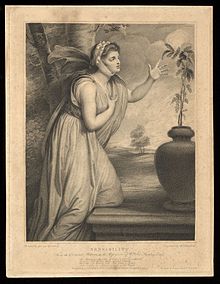

[edit]- ^ "Emma Hamilton in an attitude towards a mimosa plant, causing it to demonstrate sensibility. Stipple engraving by R. Earlom, 1789, after G. Romney".

- ^ J. Locke, An Essay Concerning Humane Understanding (London, 1690), p. 44.

- ^ Johnson, Samuel. The Idler, No. 100.

- ^ Todd, Janet (1986). Sensibility: An introduction. London: Methuen. ISBN 9780416377200.

- ^ Johnson, Claudia (1995). Equivocal Beings: Politics, Gender, and Sentimentality in the 1790s--Wollstonecraft, Radcliffe, Burney, Austen. Chicago: Chicago UP. ISBN 978-0226401843.

- ^ Trumpener, Katie (1997). Bardic Nationalism: The Romantic Novel and the British Empire. Princeton: Princeton UP. ISBN 978-0691044804.

Further reading

[edit]- Barker-Benfield, G.J. The Culture of Sensibility: Sex and Society in Eighteenth-Century Britain. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992.

- Brissenden, R. F. Virtue in Distress: Studies in the Novel of Sentiment from Richardson to Sade. New York: Barnes and Noble, 1974.

- Crane, R.S. “Suggestions Toward a Genealogy of the ‘Man of Feeling.’” ELH 1.3 (1934): 205-230.

- Ellis, Markman. The Politics of Sensibility: Race, Gender and Commerce in the Sentimental Novel. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

- Ellison, Julie. Cato’s Tears and the Making of Anglo-American Emotion. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999.

- Goring, Paul. The Rhetoric of Sensibility in Eighteenth-Century Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

- Jones, Chris. Radical Sensibility: Literature and ideas in the 1790s. London: Routledge, 1993.

- McGann, Jerome. The Poetics of Sensibility: a Revolution in Literary Style. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996.

- Mullan, John. Sentiment and Sociability: The Language of Feeling in the Eighteenth Century. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988.

- Nagle, Christopher. Sexuality and the Culture of Sensibility in the British Romantic Era. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007.

- Pinch, Adela. Strange Fits of Passion: Epistemologies of Emotion, Hume to Austen. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1996.

- Rousseau, G.S. “Nerves, Spirits, and Fibres: Towards Defining the Origins of Sensibility.” Studies in the Eighteenth Century 3: Papers Presented at the Third David Nichol Smith Memorial Seminar, Canberra 1973. Ed. R.F. Brissenden and J.C. Eade. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1976.

- Tompkins, Jane. Sensational Designs: The Cultural Work of American Fiction 1790-1860. New York: Oxford University Press, 1986.

- Van Sant, Ann Jessie. Eighteenth-Century Sensibility and the Novel: The senses in social context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

External links

[edit]- "Sensibility", BBC Radio 4 discussion with Claire Tomalin, John Mullan and Hermione Lee (In Our Time, Jan. 3, 2002)