Secondary source

In scholarship, a secondary source[1][2] is a document or recording that relates or discusses information originally presented elsewhere. A secondary source contrasts with a primary, or original, source of the information being discussed. A primary source can be a person with direct knowledge of a situation or it may be a document created by such a person.

A secondary source is one that gives information about a primary source. In a secondary source, the original information is selected, modified and arranged in a suitable format. Secondary sources involve generalization, analysis, interpretation, or evaluation of the original information.

The most accurate classification for any given source is not always obvious. Primary and secondary are relative terms, and some sources may be classified as primary or secondary, depending on how they are used.[3][4][5][6] A third level, the tertiary source, such as an encyclopedia or dictionary, resembles a secondary source in that it contains analysis, but a tertiary source has a different purpose; it aims to elaborate a broad introductory overview of the topic at hand.[1][7]

Classification of sources

[edit]Information can be interpreted from a wide variety of found objects, but source classification for primary or secondary status, etc., is applicable only to symbolic sources, which are those objects meant to communicate information, either publicly or privately, to some person, known or unknown. Typical symbolic sources include written documents such as letters, notes, receipts, ledgers, manuscripts, reports, or public signage, or graphic art, etc,; but do not include, for example, bits of broken pottery or scraps of food excavated from a midden—and this regardless of how much information can be extracted from an ancient trash heap, or how little can be extracted from a written document.[8]

Making distinctions between primary and secondary symbolic sources is both subjective and contextual,[9] such that precise definitions can sometimes be difficult to make.[10] And indeed many sources can be classified as either primary or secondary based upon the context in which they are being considered.[8] For example, if in careful study a historical text discusses certain old documents to the point of disclosing a new historical conclusion, then that historical text may now be considered a primary source for the new conclusion, but it is still a secondary source as regarding the old documents.[11] Other examples for which a source can be assigned both primary and secondary roles would include an obituary or a survey of several volumes of a journal to count the frequency of articles on a certain topic.[12]

Further, whether a source is regarded as primary or secondary in a given context may change over time, depending upon the past and present states of knowledge within the field of study.[13] For example, if a certain document refers to the contents of a previous but undiscovered letter, that document may be considered "primary", because it is the closest known thing to an original source—but if the missing letter is later found, that certain document may then be considered "secondary".[14]

Attempts to map or model scientific and scholarly communications need the concepts of primary, secondary and further "levels" of classification. One such model is provided by the United Nations as the UNISIST model of information dissemination. Within such a model, source classification concepts are defined in relation to each other, and acceptance of a particular way of defining the concepts for classification are connected to efficiently using the model. (Note: UNISIST is the United Nations International Scientific Information System; it is a model of a social system for communications between knowledge producers, knowledge users, and their intermediaries. The system also comprises institutions such as libraries, research institutes, and publishers.) [15]

Some modern languages use more than one word for the English word "source". German usually uses Sekundärliteratur ("secondary literature") for secondary sources regarding historical facts, leaving Sekundärquelle ("secondary source") to historiography. A Sekundärquelle may be a source, perhaps a letter, that quotes from a lost Primärquelle ("primary source")—say a report of minutes that is not known to still exist—such that the report of minutes is unavailable to the researcher as the sought-after Primärquelle.

Science, technology, and medicine

[edit]In general, secondary sources in a scientific context may be referred to as "secondary literature",[16] and can be self-described as review articles or meta-analysis.

Primary source materials are typically defined as "original research papers written by the scientists who actually conducted the study." An example of primary source material is the Purpose, Methods, Results, Conclusions sections of a research paper (in IMRAD style) in a scientific journal by the authors who conducted the study.[17] In some fields, a secondary source may include a summary of the literature in the introduction of a scientific paper, a description of what is known about a disease or treatment in a chapter in a reference book, or a synthesis written to review available literature.[17] A survey of previous work in the field in a primary peer-reviewed source is secondary source information. This allows secondary sourcing of recent findings in areas where full review articles have not yet been published.

A book review that contains the judgment of the reviewer about the book is a primary source for the reviewer's opinion, and a secondary source for the contents of the book.[18][19] A summary of the book within a review is a secondary source.

Library and information science

[edit]In library and information sciences, secondary sources are generally regarded as those sources that summarize or add commentary to primary sources in the context of the particular information or idea under study.[1][2]

Mathematics

[edit]An important use of secondary sources in the field of mathematics has been to make difficult mathematical ideas and proofs from primary sources more accessible to the public;[20] in other sciences tertiary sources are expected to fulfill the introductory role.

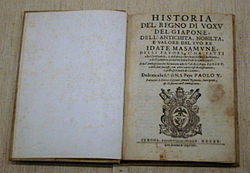

Humanities and history

[edit]Secondary sources in history and humanities are usually books or scholarly journals, from the perspective of a later interpreter, especially by a later scholar. In the humanities, a peer reviewed article is always a secondary source. The delineation of sources as primary and secondary first arose in the field of historiography, as historians attempted to identify and classify the sources of historical writing. In scholarly writing, an important objective of classifying sources is to determine the independence and reliability of sources.[21] In original scholarly writing, historians rely on primary sources, read in the context of the scholarly interpretations.[22]

Following the Rankean model established by German scholarship in the 19th century, historians use archives of primary sources.[23] Most undergraduate research projects rely on secondary source material, with perhaps snippets of primary sources.[24]

Law

[edit]In the legal field, source classification is important because the persuasiveness of a source usually depends upon its history. Primary sources may include cases, constitutions, statutes, administrative regulations, and other sources of binding legal authority, while secondary legal sources may include books, the headnotes of case reports, articles, and encyclopedias.[25] Legal writers usually prefer to cite primary sources because only primary sources are authoritative and precedential, while secondary sources are only persuasive at best.[26]

Family history

[edit]"A secondary source is a record or statement of an event or circumstance made by a non-eyewitness or by someone not closely connected with the event or circumstances, recorded or stated verbally either at or sometime after the event, or by an eye-witness at a time after the event when the fallibility of memory is an important factor."[27] Consequently, according to this definition, a first-hand account written long after the event "when the fallibility of memory is an important factor" is a secondary source, even though it may be the first published description of that event.

Autobiographies

[edit]An autobiography or a memoir can be a secondary source in history or the humanities when used for information about topics other than its subject.[28] For example, many first-hand accounts of events in World War I written in the post-war years were influenced by the then prevailing perception of the war, which was significantly different from contemporary opinion.[29]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Primary, secondary and tertiary sources". University Libraries, University of Maryland.

- ^ a b "Secondary sources Archived 2014-11-06 at the Wayback Machine". James Cook University.

- ^ "Primary and secondary sources". Ithaca College Library.

- ^ Kragh, Helge (1989), An Introduction to the Historiography of Science, Cambridge University Press, p. 121, ISBN 0-521-38921-6,

[T]he distinction is not a sharp one. Since a source is only a source in a specific historical context, the same source object can be both a primary or secondary source according to what it is used for.

- ^ Delgadillo, Roberto; Lynch, Beverly (1999), "Future Historians: Their Quest for Information", College & Research Libraries, 60 (3): 245–259, at 253, doi:10.5860/crl.60.3.245,

[T]he same document can be a primary or a secondary source depending on the particular analysis the historian is doing

, - ^ Monagahn, E.J.; Hartman, D.K. (2001), "Historical research in literacy", Reading Online, 4 (11), archived from the original on 2012-02-13, retrieved 2022-01-21,

[A] source may be primary or secondary, depending on what the researcher is looking for.

- ^ Richard Veit and Christopher Gould, Writing, Reading, and Research (8th ed. 2009) p 335

- ^ a b Kragh, Helge (1989-11-24). An Introduction to the Historiography of Science. Cambridge University Press. p. 121. ISBN 9780521389211.

- ^ Dalton, Margaret Steig; Charnigo, Laurie (September 2004). "Historians and Their Information Sources". College & Research Libraries: 416 n.3, 419 n.18.

- ^ Delgadillo & Lynch 1999, p. 253.

- ^ "Important Sources of History (Primary and Secondary Sources)". History Discussion - Discuss Anything About History. 2013-09-23. Retrieved 2020-02-06.

- ^ Duffin, Jacalyn (1999), History of Medicine: A Scandalously Short Introduction, University of Toronto Press, p. 366, ISBN 0-8020-7912-1

- ^ Henige, David (1986), "Primary Source by Primary Source? On the Role of Epidemics in New World Depopulation", Ethnohistory, 33 (3), Duke University Press: 292–312, at 292, doi:10.2307/481816, JSTOR 481816, PMID 11616953,

[T]he term 'primary' inevitably carries a relative meaning insofar as it defines those pieces of information that stand in closest relationship to an event or process in the present state of our knowledge. Indeed, in most instances, the very nature of a primary source tells us that it is actually derivative.…[H]istorians have no choice but to regard certain of the available sources as 'primary' since they are as near to truly original sources as they can now secure.

- ^ Henige 1986, p. 292.

- ^ "UNISIST Study Report on the feasibility of a World Science Information System, by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization and the International Council of Scientific Unions". Unesco, Paris, 1971.

- ^ Open University, "4.2 Secondary literature", Succeeding in postgraduate study, session 5, accessed 22 March 2023.

- ^ a b Garrard, Judith (2010). Health Sciences Literature Review Made Easy. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4496-1868-1. Retrieved 16 September 2012.

- ^ Princeton (2011). "Book reviews". Scholarly definition document. Princeton. Retrieved September 22, 2011.

- ^ Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University (2011). "Book reviews". Scholarly definition document. Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University. Archived from the original on September 10, 2011. Retrieved September 22, 2011.

- ^ Edwards, H.M. (2001), Riemann's Zeta Function, Mineola, New York: Courier Dover Publications, p. xi, ISBN 0-486-41740-9,

The purpose of a secondary source is to make the primary sources accessible to you. If you can read and understand the primary sources without reading this book, more power to you. If you read this book without reading the primary sources you are like a man who carries a sack lunch to a banquet

- ^ Helge (1989), p. 121.

- ^ Cipolla (1992), Between Two Cultures: An Introduction to Economic History, W.W. Norton & Co., ISBN 978-0-393-30816-7

- ^ Frederick C. Beiser (2011). The German Historicist Tradition. Oxford U.P. p. 254. ISBN 9780199691555.

- ^ Charles Camic; Neil Gross; Michele Lamont (2011). Social Knowledge in the Making. U. of Chicago Press. p. 107. ISBN 9780226092096.

- ^ Bouchoux, Deborah E. (2000), Cite Checker: A Hands-On Guide to Learning Citation Form, Thomson Delmar Learning, p. 45, ISBN 0-7668-1893-4

- ^ Bouchoux 2000, p. 45.

- ^ Harland, p. 39

- ^ Wallach, Jennifer J. (2006). "Building a bridge of words: the literary autobiography as historical source material". Biography. 29 (3): 446–61. Retrieved 18 November 2024.

- ^ Holmes, particularly the introduction

Further reading

[edit]- Jules R. Benjamin, A Student's Guide to History (2013) ISBN 9781457621444

- Edward H. Carr, What is History? (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2001) ISBN 9780333977019

- Wood Gray, Historian's handbook, a key to the study and writing of history (Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press, 1991, ©1964) ISBN 9780881336269

- Derek Harland, A Basic Course in Genealogy: Volume two, Research Procedure and Evaluation of Evidence (Bookcraft Inc, 1958) WorldCat record

- Richard Holmes, Tommy (HarperCollins, 2004) ISBN 9780007137510

- Martha C. Howell and Walter Prevenier, From Reliable Sources: An Introduction to Historical Methods (2001) ISBN 9780801435737

- Richard A. Marius and Melvin E. Page, A Short Guide to Writing About History (8th Edition) (2012) ISBN 9780205118601

- Hayden White, Metahistory: the historical imagination in nineteenth-century Europe (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1973) ISBN 9780801814693