Sea spider

| Sea spiders Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Left to right, top to bottom: Austrodecus bamberi (Austrodecidae), Colossendeis sp. (Colossendeidae), Pycnogonum stearnsi (Pycnogonidae), Ammothea hilgendorfi (Ammotheidae), Endeis flaccida (Endeinae), Nymphon signatum (Nymphonidae) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Chelicerata |

| Class: | Pycnogonida Latreille, 1810 |

| Order: | Pantopoda Gerstaecker, 1863 |

| Type genus | |

| Pycnogonum Brünnich, 1764

| |

| Families | |

|

See text. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Arachnopoda Dana, 1853 | |

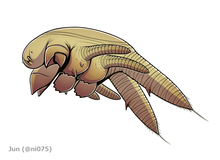

Sea spiders are marine arthropods of the order Pantopoda[1] (lit. ‘all feet’[2]), belonging to the class Pycnogonida,[3] hence they are also called pycnogonids (/pɪkˈnɒɡənədz/;[4] named after Pycnogonum, the type genus;[5] with the suffix -id). They are cosmopolitan, found in oceans around the world. The over 1,300 known species have leg spans ranging from 1 mm (0.04 in) to over 70 cm (2.3 ft).[6] Most are toward the smaller end of this range in relatively shallow depths; however, they can grow to be quite large in Antarctic and deep waters.

Although "sea spiders" are not true spiders, nor even arachnids, their traditional classification as chelicerates would place them closer to true spiders than to other well-known arthropod groups, such as insects or crustaceans, if correct. This is disputed, however, as genetic evidence suggests they may be a sister group to all other living arthropods.[7][8]

Description

[edit]

Sea spiders have long legs in contrast to a small body size. The number of walking legs is usually eight (four pairs), but the family Pycnogonidae includes species with five pairs, and the families Colossendeidae and Nymphonidae include species with both five and six pairs.[9] There are nine polymerous (i.e., extra-legged) species: seven species distributed among four genera (Decolopoda, Pentacolossendeis, Pentapycnon, and Pentanymphon) with five leg pairs and two species in two genera (Dodecolopoda and Sexanymphon) with six leg pairs.[10] Pycnogonids do not require a traditional respiratory system. Instead, gasses are absorbed by the legs and transferred through the body by diffusion. A proboscis allows them to suck nutrients from soft-bodied invertebrates, and their digestive tract has diverticula extending into the legs.

Certain pycnogonids are so small that each of their very tiny muscles consists of a single cell, surrounded by connective tissue. The anterior region (cephalon) consists of the proboscis, which has fairly limited dorsoventral and lateral movement, the ocular tubercle with eyes, and up to four pairs of appendages. The first of these are the chelifores, followed by the palps, the ovigers, which are used for cleaning themselves and caring for eggs and young as well as courtship, and the first pair of walking legs. Nymphonidae is the only family where both the chelifores and the palps are functional. In the others the chelifores or palps, or both, are reduced or absent. In some families, also the ovigers can be reduced or missing in females, but are always present in males.[11] In those species that lack chelifores and palps, the proboscis is well developed and flexible, often equipped with numerous sensory bristles and strong rasping ridges around the mouth. The last segment includes the anus and tubercle, which projects dorsally.

In total, pycnogonids have four to six pairs of legs for walking. A cephalothorax and a much smaller unsegmented abdomen make up the extremely reduced body of the pycnogonid, which has up to two pairs of dorsally located simple eyes on its non-calcareous exoskeleton, though sometimes the eyes can be missing, especially among species living in the deep oceans. The abdomen does not have any appendages, and in most species it is reduced and almost vestigial. The organs of this chelicerate extend throughout many appendages because its body is too small to accommodate all of them alone.

The morphology of the sea spider creates an efficient surface-area-to-volume ratio for respiration to occur through direct diffusion. Oxygen is absorbed by the legs and is transported via the hemolymph to the rest of the body.[12] The most recent research seems to indicate that waste leaves the body through the digestive tract or is lost during a moult.[citation needed] The small, long, thin pycnogonid heart beats vigorously at 90 to 180 beats per minute, creating substantial blood pressure. The beating of the sea spider heart drives circulation in the trunk and in the part of the legs closest to the trunk, but is not important for the circulation in the rest of the legs.[12][13] Hemolymph circulation in the legs is mostly driven by the peristaltic movement in the part of the gut that extends into every leg, a process called gut peristalsis.[12][13] These creatures possess an open circulatory system as well as a nervous system consisting of a brain which is connected to two ventral nerve cords, which in turn connect to specific nerves.

Reproduction and development

[edit]

All pycnogonid species have separate sexes, except for one species that is hermaphroditic.[citation needed] Females possess a pair of ovaries, while males possess a pair of testes located dorsally in relation to the digestive tract. Reproduction involves external fertilisation after "a brief courtship".[citation needed] Only males care for laid eggs and young.[citation needed]

The larva has a blind gut and the body consists of a head and its three pairs of cephalic appendages only: the chelifores, palps and ovigers. The abdomen and the thorax with its thoracic appendages develop later. One theory is that this reflects how a common ancestor of all arthropods evolved; starting its life as a small animal with a pair of appendages used for feeding and two pairs used for locomotion, while new segments and segmental appendages were gradually added as it was growing.

At least four types of larvae have been described: the typical protonymphon larva, the encysted larva, the atypical protonymphon larva, and the attaching larva. The typical protonymphon larva is most common, is free living and gradually turns into an adult. The encysted larva is a parasite that hatches from the egg and finds a host in the shape of a polyp colony where it burrows into and turns into a cyst, and will not leave the host before it has turned into a young juvenile.[14]

Little is known about the development of the atypical protonymphon larva. The adults are free living, while the larvae and the juveniles are living on or inside temporary hosts such as polychaetes and clams. When the attaching larva hatches it still looks like an embryo, and immediately attaches itself to the ovigerous legs of the father, where it will stay until it has turned into a small and young juvenile with two or three pairs of walking legs ready for a free-living existence.

Distribution and ecology

[edit]

These animals live in many different parts of the world, from Australia, New Zealand, and the Pacific coast of the United States, to the Mediterranean Sea and the Caribbean Sea, to the north and south poles. They are most common in shallow waters, but can be found as deep as 7,000 metres (23,000 ft), and live in both marine and estuarine habitats. Pycnogonids are well camouflaged beneath the rocks and among the algae that are found along shorelines.

Sea spiders either walk along the bottom with their stilt-like legs or swim just above it using an umbrella pulsing motion.[15] Sea spiders are mostly carnivorous predators or scavengers that feed on cnidarians, sponges, polychaetes, and bryozoans. Although they can feed by inserting their proboscis into sea anemones, which are much larger, most sea anemones survive this ordeal, making the sea spider a parasite rather than a predator of anemones. Sea spiders might also be endoparasites of clams.[16]

Classification

[edit]The class Pycnogonida comprises over 1,300 species, which are normally split into eighty-six genera. The correct taxonomy within the group is uncertain, and it appears that no agreed list of orders exists. All families are considered part of the single order Pantopoda.

Sea spiders have long been considered to belong to the Chelicerata, together with horseshoe crabs, and the Arachnida, which includes spiders, mites, ticks, scorpions, and harvestmen, among other lesser-known orders.[17]

A competing hypothesis proposes that Pycnogonida belong to their own lineage, distinct from chelicerates, crustaceans, myriapods, or insects. This Cormogonida hypothesis contended that the sea spider's chelifores, which are unique among extant arthropods, are not positionally homologous to the chelicerae of Chelicerata, as was previously supposed. Instead of developing from the deutocerebrum like the chelicerae, the sea spider chelifores were thought to be innervated by the protocerebrum, the anterior part of the arthropod brain and found in the first head segment that in all other arthropods give rise to the eyes and the labrum. This condition of having protocerebral appendages is not found anywhere else among arthropods, except in fossil forms like Anomalocaris, which was taken as evidence that Pycnogonida may be a sister group to all other living arthropods, the latter having evolved from some ancestor that had lost the protocerebral appendages. If this result had been confirmed, it would have meant the sea spiders are the last surviving (and highly modified) members of an ancient stem group of arthropods that lived in Cambrian oceans.[18] However, a subsequent study using Hox gene expression patterns demonstrated the developmental homology between chelicerates and chelifores, with chelifores innervated by a deuterocerebrum that has been rotated forwards; thus, the protocerebral Great Appendage clade does not include the Pycnogonida.[19][20][21]

Phylogenomic studies place the Pycnogonida as the sister group to the remaining Chelicerata (consistent with the chelifore-chelicera putative homology[22]), though few other relationships at the base of the chelicerates are well resolved.[23][24][25][26] The first phylogenomic study of sea spiders was able to establish a backbone tree for the group and showed that Austrodecidae is the sister group to the remaining families.[27]

Group taxonomy

[edit]According to the World Register of Marine Species, the order Pantopoda is subdivided as follows:[28]

- suborder Eupantopodida,[29] including the following superfamilies:

- Ammotheoidea Dohrn, 1881

- Family Ammotheidae Dohrn, 1881

- Family Pallenopsidae Fry, 1978

- Ascorhynchoidea Pocock, 1904

- Family Ascorhynchidae Hoek, 1881

- Family incertae sedis

- Bango Bamber, 2004

- Bradypallene Kim & Hong, 1987 (uncertain)

- Chonothea Nakamura & Child, 1983

- Decachela Hilton, 1939

- Ephyrogymna Hedgpeth, 1943

- Hannonia Hoek, 1881

- Mimipallene Child, 1982

- Pigrogromitus Calman, 1927

- Pycnopallene Stock, 1950

- Pycnothea Loman, 1921

- Queubus Barnard, 1946

- Ammotheoidea Dohrn, 1881

- Colossendeoidea Hoek, 1881 (Synonyms: Pycnogonoidea Pocock, 1904; Rhynchothoracoidea Fry, 1978)

- Family Colossendeidae Jarzynsky, 1870

- Family Pycnogonidae Wilson, 1878

- Family Rhynchothoracidae Thompson, 1909

- Nymphonoidea Pocock, 1904

- Family Callipallenidae Hilton, 1942

- Family Nymphonidae Wilson, 1878

- Phoxichilidioidea Sars, 1891

- Family Endeidae Norman, 1908

- Family Phoxichilidiidae Sars, 1891

- Colossendeoidea Hoek, 1881 (Synonyms: Pycnogonoidea Pocock, 1904; Rhynchothoracoidea Fry, 1978)

- suborder Stiripasterida Fry, 1978,[30] including the following family:

- Family Austrodecidae Stock, 1954

- suborder incertae sedis,[31] including the following genera and families:

- †Palaeopycnogonididae Sabroux, Edgecombe, Pisani & Garwood, 2023

- †Flagellopantopus Poschmann & Dunlop, 2005

- †Palaeothea Bergstrom, Sturmer & Winter, 1980

- Alcynous Costa, 1861 (nomen dubium)

- Foxichilus Costa, 1836 (nomen dubium)

- Oiceobathys Hesse, 1867 (nomen dubium)

- Oomerus Hesse, 1874 (nomen dubium)

- Paritoca Philippi, 1842 (nomen dubium)

- Pephredro Goodsir, 1842 (nomen dubium)

- Phanodemus Costa, 1836 (nomen dubium)

- Platychelus Costa, 1861 (nomen dubium)

Fossil record

[edit]The fossil record of pycnogonids is scant. The earliest fossils are known from the Cambrian 'Orsten' of Sweden (Cambropycnogon), though some researchers have argued that this putative larval sea spider is not a pycnogonid at all.[27] Unambiguous sea spider body fossils include the Silurian Coalbrookdale Formation of England (Haliestes) and the Devonian Hunsrück Slate of Germany (Flagellopantopus, Palaeopantopus, Palaeoisopus, Palaeothea and Pentapantopus). Some of these specimens are significant in that they possess a longer 'trunk' behind the abdomen and in two fossils the body ends in a tail, something never seen in living sea spiders.

The first fossil pycnogonid found within an Ordovician deposit (Palaeomarachne) was reported in 2013, found in William Lake Provincial Park, Manitoba.[32][a]

Remarkably well preserved fossils were exposed in fossil beds at La Voulte-sur-Rhône in 2007, south of Lyon in south-eastern France. Researchers from the University of Lyon discovered about 70 fossils from three distinct species in the 160 million-year-old Jurassic La Voulte Lagerstätte. The find will help fill in an enormous gap in the history of these creatures.[33]

Footnotes

[edit]- ^

"Here we report the first known occurrence of fossil pycnogonids from rocks of Ordovician age, bridging a 65 Myr gap between controversial late Cambrian larval forms and a single documented Silurian specimen. The new taxon, Palaeomarachne granulata n. gen. n. sp., [is] from the Upper Ordovician (c. 450 Ma) William Lake Konservat-Lagerstätte deposit in Manitoba, Canada; [it] is also the first reported from Laurentia. It is the only record thus far of a fossil sea spider in rocks of demonstrably shallow marine origin." — Rudkin et al. (2013), p. 395[32]

References

[edit]- ^ "Pycnogonida". World Register of Marine Species. Taxon details.

- ^ "Pantopoda". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster.: "taxonomic synonym of Pycnogonida < Neo-Latin, from pant- + -poda"

- ^ "Pycnogonida". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster.: "New Latin, from Pycnogonum [...] + -ida"

- ^ "pycnogonid". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster.

- ^ "pycnogonid". The Free Dictionary.

From Neo-Latin Pycnogonida, class name, from Pycnogonum, type genus.

- ^ "Sea spiders provide insights into Antarctic evolution" (Press release). Department of the Environment and Energy, Australian Antarctic Division. 22 July 2010. Archived from the original on 31 July 2018. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- ^ Regier, Jerome C.; Shultz, Jeffrey W.; Zwick, Andreas; Hussey, April; Ball, Bernard; Wetzer, Regina; Martin, Joel W.; Cunningham, Clifford W. (2010). "Arthropod relationships revealed by phylogenomic analysis of nuclear protein-coding sequences". Nature. 463 (7284): 1079–83. Bibcode:2010Natur.463.1079R. doi:10.1038/nature08742. PMID 20147900. S2CID 4427443.

- ^ Sharma, P. P.; Kaluziak, S. T.; Perez-Porro, A.R.; Gonzalez, V. L.; Hormiga, G.; Wheeler, W. C.; Giribet, G. (2014). "Phylogenomic Interrogation of Arachnida Reveals Systemic Conflicts in Phylogenetic Signal". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 31 (11): 2963–84. doi:10.1093/molbev/msu235. PMID 25107551.

- ^ Ruppert, Edward E. (1994). Invertebrate Zoology. Barnes, Robert D. (6th ed.). Fort Worth, TX: Saunders College Pub. ISBN 0-03-026668-8. OCLC 30544625.

- ^ Crooker, Allen (2008). "Sea Spiders (Pycnogonida)". In Capinera, John L. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Entomology. Dordrecht, NL: Springer Netherlands. pp. 3321–3335. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-6359-6_4098. ISBN 978-1-4020-6359-6.

- ^ Phylogenomic Resolution of Sea Spider Diversification through Integration of Multiple Data Classes

- ^ a b c Woods, H. Arthur; Lane, Steven J.; Shishido, Caitlin; Tobalske, Bret W.; Arango, Claudia P.; Moran, Amy L. (2017-07-10). "Respiratory gut peristalsis by sea spiders". Current Biology. 27 (13): R638–R639. Bibcode:2017CBio...27.R638W. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2017.05.062. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 28697358. S2CID 35014992.

- ^ a b Bastide, A.; Peretti, D.; Knight, J. R.; Grosso, S.; Spriggs, R. V.; Pichon, X.; Sbarrato, T.; Roobol, A.; Roobol, J.; Vito, D.; Bushell, M.; von Der Haar, T.; Smales, C. M.; Mallucci, G. R.; Willis, A. E. (2017). "RTN3 is a Novel Cold-Induced Protein and Mediates Neuroprotective Effects of RBM3". Current Biology. 27 (5): 638–650. Bibcode:2017CBio...27..638B. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2017.01.047. PMC 5344685. PMID 28238655.

- ^ Bain, B. A. (2003). "Larval types and a summary of postembryonic development within the pycnogonids". Invertebrate Reproduction & Development. 43 (3): 193–222. Bibcode:2003InvRD..43..193B. doi:10.1080/07924259.2003.9652540. S2CID 84345599.

- ^ McClain, Craig (August 14, 2006). "Sea Spiders". Deep Sea News Info. Archived from the original on 9 July 2007.

- ^ Yamada, Katsumasa; Miyazaki, Katsumi; Tomiyama, Takeshi; Kanaya, Gen; Miyama, Yoshifumi; Yoshinaga, Tomoyoshi; Wakui, Kunihiro; Tamaoki, Masanori; Toba, Mitsuharu (June 2018). "Impact of sea spider parasitism on host clams: susceptibility and intensity-dependent mortality". Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 98 (4): 735–742. doi:10.1017/S0025315417000200. ISSN 0025-3154.

- ^ Margulis, Lynn; Schwartz, Karlene (1998). Five Kingdoms, An Illustrated Guide to the Phyla of Life on Earth (third ed.). W.H. Freeman and Company. ISBN 978-0-7167-3027-9.[page needed]

- ^ Maxmen, Amy; Browne, William E.; Martindale, Mark Q.; Giribet, Gonzalo (2005). "Neuroanatomy of sea spiders implies an appendicular origin of the protocerebral segment". Nature. 437 (7062): 1144–8. Bibcode:2005Natur.437.1144M. doi:10.1038/nature03984. PMID 16237442. S2CID 4400419.

- ^ Jager, Muriel; Murienne, Jérôme; Clabaut, Céline; Deutsch, Jean; Guyader, Hervé Le; Manuel, Michaël (2006). "Homology of arthropod anterior appendages revealed by Hox gene expression in a sea spider". Nature. 441 (7092): 506–8. Bibcode:2006Natur.441..506J. doi:10.1038/nature04591. PMID 16724066. S2CID 4307398.

- ^ "Chelifores, chelicerae, and invertebrate evolution | ScienceBlogs". scienceblogs.com. Retrieved 2022-01-10.

- ^ Brenneis, Georg; Ungerer, Petra; Scholtz, Gerhard (2008-10-27). "The chelifores of sea spiders (Arthropoda, Pycnogonida) are the appendages of the deutocerebral segment: Chelifores of sea spiders". Evolution & Development. 10 (6): 717–724. doi:10.1111/j.1525-142X.2008.00285.x. PMID 19021742. S2CID 6048195.

- ^ Dunlop, J. A.; Arango, C. P. (2005). "Pycnogonid affinities: A review". Journal of Zoological Systematics and Evolutionary Research. 43: 8–21. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.714.8297. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0469.2004.00284.x.

- ^ Sharma, Prashant P.; Kaluziak, Stefan T.; Pérez-Porro, Alicia R.; González, Vanessa L.; Hormiga, Gustavo; Wheeler, Ward C.; Giribet, Gonzalo (November 2014). "Phylogenomic Interrogation of Arachnida Reveals Systemic Conflicts in Phylogenetic Signal". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 31 (11): 2963–2984. doi:10.1093/molbev/msu235. ISSN 1537-1719. PMID 25107551.

- ^ Ballesteros, Jesús A; Sharma, Prashant P (2019-11-01). Halanych, Ken (ed.). "A Critical Appraisal of the Placement of Xiphosura (Chelicerata) with Account of Known Sources of Phylogenetic Error". Systematic Biology. 68 (6): 896–917. doi:10.1093/sysbio/syz011. ISSN 1063-5157. PMID 30917194.

- ^ Ballesteros, Jesús A.; Santibáñez López, Carlos E.; Kováč, Ľubomír; Gavish-Regev, Efrat; Sharma, Prashant P. (2019-12-18). "Ordered phylogenomic subsampling enables diagnosis of systematic errors in the placement of the enigmatic arachnid order Palpigradi". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 286 (1917): 20192426. doi:10.1098/rspb.2019.2426. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 6939912. PMID 31847768.

- ^ Ballesteros, Jesús A; Santibáñez-López, Carlos E; Baker, Caitlin M; Benavides, Ligia R; Cunha, Tauana J; Gainett, Guilherme; Ontano, Andrew Z; Setton, Emily V W; Arango, Claudia P; Gavish-Regev, Efrat; Harvey, Mark S; Wheeler, Ward C; Hormiga, Gustavo; Giribet, Gonzalo; Sharma, Prashant P (2022-02-03). Teeling, Emma (ed.). "Comprehensive Species Sampling and Sophisticated Algorithmic Approaches Refute the Monophyly of Arachnida". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 39 (2): msac021. doi:10.1093/molbev/msac021. ISSN 0737-4038. PMC 8845124. PMID 35137183.

- ^ a b Ballesteros, Jesús A; Setton, Emily V W; Santibáñez-López, Carlos E; Arango, Claudia P; Brenneis, Georg; Brix, Saskia; Corbett, Kevin F; Cano-Sánchez, Esperanza; Dandouch, Merai; Dilly, Geoffrey F; Eleaume, Marc P; Gainett, Guilherme; Gallut, Cyril; McAtee, Sean; McIntyre, Lauren (2021-01-23). Crandall, Keith (ed.). "Phylogenomic Resolution of Sea Spider Diversification through Integration of Multiple Data Classes". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 38 (2): 686–701. doi:10.1093/molbev/msaa228. ISSN 1537-1719. PMC 7826184. PMID 32915961.

- ^ "WoRMS - World Register of Marine Species - Pantopoda". marinespecies.org. Retrieved 2023-12-04.

- ^ "WoRMS - World Register of Marine Species - Eupantopodida". marinespecies.org. Retrieved 2023-12-04.

- ^ "WoRMS - World Register of Marine Species - Stiripasterida". marinespecies.org. Retrieved 2023-12-04.

- ^ "WoRMS - World Register of Marine Species - Pantopoda incertae sedis". marinespecies.org. Retrieved 2023-12-04.

- ^ a b Rudkin, Dave; Cuggy, Michael B.; Young, Graham A.; Thompson, Deborah P. (2013). "An Ordovician pycnogonid (sea spider) with serially subdivided 'head' region". Journal of Paleontology. 87 (3): 395–405. Bibcode:2013JPal...87..395R. doi:10.1666/12-057.1. S2CID 83924778. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- ^ "Fossil sea spiders thrill experts". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. 16 August 2007. Retrieved 3 Nov 2024.