Schuyler Cammann

Schuyler Cammann | |

|---|---|

| Born | Schuyler Van Rensselaer Cammann February 2, 1912 New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Died | September 9, 1991 (aged 79) |

| Education | St. Paul's School Kent School |

| Alma mater | Yale University Harvard University Johns Hopkins University |

| Occupation(s) | Professor Emeritus Department of Oriental Studies Curator Emeritus of the University Museum |

| Employer | University of Pennsylvania |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 5 |

Schuyler Van Rensselaer Cammann (February 2, 1912, in New York City – September 9, 1991, in Sugar Hill, New Hampshire) was an anthropologist best known for work in Asia.[1]

Early life

[edit]Cammann was born on February 2, 1912, in New York City.[2] He was the son of Herbert Schuyler Cammann (1884–1965)[3] and Katharine Van Rensselaer Fairfax (1888–1978).[4] His father, a great-grandson of Robert Fulton, inventor of the steamboat, was involved in real estate and insurance business he established in 1907.[3] His sister, Katharine Schuyler Cammann,[5] was married to Howard S. Lipson of Sugar Hill, New Hampshire.[6]

His paternal grandparents were Hermann Henry Cammann (d. 1930),[7] a former trustee of Columbia University and governor of New York Presbyterian Hospital, and Ella Crary Cammann.[6] His maternal grandparents were Hamilton Rogers Fairfax, of the Fairfax family of Virginia, and Eleanor Cecilia (née Van Rensselaer) Fairfax of the Van Rensselaer family of New York.[8] His grandmother was the granddaughter of Stephen Van Rensselaer III and Cornelia (née Paterson) Van Rensselaer.[8] His maternal uncle was Hamilton Van Rensselaer Fairfax (1891–1955).[4]

Cammann attended St. Paul's School on Long Island and Kent School in Kent, Connecticut, graduating in 1931.[9] Camman later graduated from Yale University with a BA in 1935, Harvard University with an MA in 1941, and from Johns Hopkins University with a Ph.D. in 1949, where he studied under Owen Lattimore.[1]

Career

[edit]From 1935 to 1941 he taught English in the Yale-in-China program. During World War II, he served as a lieutenant in the United States Navy, stationed in Washington D.C., and later in Western China and Inner Mongolia.[1]

In 1948, he joined the faculty of the Department of Oriental Studies at the University of Pennsylvania, which was founded by W. Norman Brown in 1931. He remained in the department until his retirement in 1982.[1] From 1948 through 1955, he was the Associate Curator of the East Asian Collections for the University of Pennsylvania Museum.[10] While at the museum, he was a member of excavation teams at Gordium (the capital city of ancient Phrygia in modern-day Turkey) and Kunduz (a city in northern Afghanistan). From 1951 until 1955, he was also a panel member for the television show What in the World?.[1]

Cammann served as vice-president of the American Oriental Society and was the editor of the Journal of the American Oriental Society.[11] He also served as president of the Philadelphia Anthropological Society and Oriental Club of Philadelphia, and was a fellow of the American Learned Societies and the American Anthropological Association.[1]

Legacy

[edit]

According to the History of Chinese Science and Culture Foundation, Cammann was

"a man of independent means who had no academic ambitions or need for a salary. His independence of 'the system' caused envy amongst several of his colleagues, who unlike himself were very ambitious for promotion. Even though he was a mild, polite, and gentle person of great friendliness, he experienced rebuffs and ostracism from several colleagues which were undeserved. He endured these affronts with great patience and tolerance."[12]

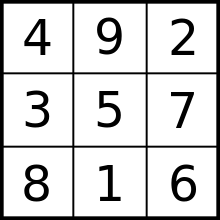

Cammann was also very interested in Chinese magic squares, which the Foundation further described:

"One of Cammann's other great passions was for Chinese magic squares, concerning which he made detailed studies and published various articles. He was a pioneer in realizing the importance and significance of magic squares, and his work laid the ground work for their wider appreciation today amongst scholars, as well as enriching the field for the many studies of them by mathematicians which today are increasingly common."[12]

Cammann wrote several articles exploring the history of magic squares in China and India.

Personal life

[edit]In February 1943,[13] Cammann was married to Marcia de Forest Post at St. John's Chapel of the Washington Cathedral.[13] She was the daughter of Charles Addison Post, of Providence, Rhode Island, and Marcia de Forest Post of Hamilton, Bermuda, and granddaughter of Mrs. Isaac Judson Boothe of Providence.[14] Together, they were the parents of five children: Francis Cammann, Stephen Van Rensselaer Cammann, Hamilton Cammann, Elizabeth Cammann, and William Cammann.[1]

On December 27, 1980, he married Mary Lyman Muir in Philadelphia.[15][16] Mary was the widow of John Brinley Muir, a stockbroker, and the daughter of John Lyman Cox[citation needed], an engineer and inventor.[16]

Cammann died in an auto accident on September 9, 1991, near his summer home in Sugar Hill, New Hampshire.[1]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h "Schuyler V. R. Cammann papers, 1946-1991". dla.library.upenn.edu. University of Pennsylvania: Penn Museum Archives. Retrieved 30 November 2017.

- ^ "Son Born to Mrs. H.S. Cammann". The New York Times. 6 February 1912. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- ^ a b "SCHUYLER CAMMANN, A REAL-ESTATE MAN". The New York Times. 4 March 1965. Retrieved 30 November 2017.

- ^ a b "MISS FAIRFAX WEDS IN GRACE CHURCH | Only Daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Hamilton R. Fairfax Married to H. Schuyler Cammann. CHOIR MEETS BRIDAL PARTY Flower Girl Faints During Ceremony -- Reception at Fairfax Home, Where Couple Receives Under Floral Bell". The New York Times. 19 April 1911. Retrieved 30 November 2017.

- ^ "MISS K. S. CAMMANN MAKES HER DEBUT; Large Tea Dance Given for Her by Parents in Roof Garden of the Pierre. GUESTS ARE OF YOUNG SET Debutante Gowned in Aqua Marine Blue Crepe and Mother in Fuchsia-Colored Velvet". The New York Times. 17 December 1933. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- ^ a b "Katharine S. Cammann to Be Bride Of Howard S. Lipson Late in April; Mr. and Mrs. H. Schuyler Cammann Announce Betrothal of Their Only Daughter--She Is Descended From Prominent Families--Fiance Yale Alumnus". The New York Times. 11 March 1937. Retrieved 30 November 2017.

- ^ "H.H. CAMMANN DIES AT THE AGE OF 85; He Was Active for Half a Century as a Realty Man in This City. WAS TRUSTEE OF COLUMBIA Also for Many Years Controller of Trinity Parish--Initiated the Fulton Trust Company". The New York Times. 21 December 1930. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- ^ a b Glenn, Thomas Allen (1898). Some Colonial Mansions: And Those who Lived in Them : with Genealogies of the Various Families Mentioned. H. T. Coates. p. 468. Retrieved 30 November 2017.

- ^ "Sill Society Recognizes Four New Inductees in 2010", Kent Quarterly, vol. XXXVI.3, Summer 2010, p. 39.

- ^ Steele, Valerie; Major, John S. (1999). China Chic: East Meets West. Yale University Press. p. 192. ISBN 0300079303. Retrieved 30 November 2017.

- ^ Appadurai, Arjun (1988). The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective. Cambridge University Press. p. 233. ISBN 9780521357265. Retrieved 30 November 2017.

- ^ a b "Schuyler Cammann". www.chinesehsc.org. The History of Chinese Science and Culture Foundation. Retrieved 30 November 2017.

- ^ a b "MARCIA DE F. POST IS WED IN CAPITAL; Bride of Ensign Schuyler Var R. Cammann in Chapel at the Washington Cathedral". The New York Times. 7 February 1943. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- ^ "ENSIGN M. DE F. POST BECOMES ENGAGED; Officer in Waves Will Be Wed to Ensign Schuyler Cammann of the Naval Reserve". The New York Times. January 11, 1943. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- ^ "Mary C. Muir Sets Bridal for Dec. 27". The New York Times. November 2, 1980. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- ^ a b "Mary Lyman Muir Bride of Professor". The New York Times. 28 December 1980. Retrieved 30 November 2017.

External links

[edit]- Schuyler V. R. Cammann papers

- Mongol Dwellings (1963) Published in Aspects of Altaic Civilization, Vol. 23 (University of Pennsylvania)

- Interchange of East and West (1959) Published in Asia Perspective (University of Pennsylvania)

- The Evolution of Magic Squares in China (University of Pennsylvania)

- Guest expert on the television show "What in the World" [1]

- Guest expert on the television show "What in the World" 2 [2]

- Interview, part 1 [3]

- Interview, part 2 [4]

- 1912 births

- 1991 deaths

- Harvard University alumni

- Johns Hopkins University alumni

- Kent School alumni

- Livingston family

- People from Sugar Hill, New Hampshire

- Scientists from New York City

- United States Navy officers

- University of Pennsylvania faculty

- Van Rensselaer family

- Yale University alumni

- 20th-century American anthropologists