Warez scene

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

The Warez scene, often referred to as The Scene,[1] is an underground network of piracy groups specialized in obtaining and illegally releasing digital media before their official release date.[2] The Scene distributes all forms of digital media, including computer games, movies, TV shows, music, and pornography.[3] This network is meant to be hidden from the public, with the files shared only with members of the community. However, as files became commonly leaked outside the community and their popularity grew, some individuals from The Scene began leaking files and uploading them to file-hosts, torrents and EDonkey Networks.

The Scene has no central leadership, location, or other organizational culture. The groups themselves create a rule set for each Scene category (for example, MP3 or TV) that then becomes the active rules for encoding material. These rule sets include a rigid set of requirements that Warez groups (shortened as "grps") must follow in releasing and managing material. The groups must follow these rules when uploading material and, if the release has a technical error or breaks a rule, other groups may "nuke" (flag as bad content) the release.[4] Groups are in constant competition to get releases up as fast as possible. First appearing around the time of Bulletin Board Systems (BBSes), The Scene is composed primarily of people dealing with and distributing media content, for which special skills and advanced software are required.

History

[edit]The Warez Scene started emerging in the 1970s, used by predecessors of software cracking and reverse engineering groups. Their work was made available on privately run bulletin board systems (BBSes).[5] The first BBSes were located in the United States, but similar boards started appearing in Canada, the United Kingdom, Australia, and mainland Europe. At the time, setting up a machine capable of distributing data was not trivial, and required a certain amount of technical skill; this was usually taken on as a technical challenge. The BBSes typically hosted several megabytes of material, with the best boards having multiple phone lines, and up to one hundred megabytes of storage space, a considerable expense at the time.[6] Releases were mostly games and later software.

As the world of software development evolved to counter the distribution of material, and as the software and hardware needed for distribution became readily available to anyone, The Scene adapted to the changes and turned from simple distribution to actual software cracking of copying restrictions and non-commercial reverse engineering.[5] As many groups of people who wanted to do this emerged, a requirement for promotion of individual groups became evident, which prompted the evolution of the artscene, which specialized in the creation of graphical art associated with individual groups.[7] The groups would promote their abilities with ever more sophisticated and advanced software, graphical art, and later also music (demoscene).[8]

The subcommunities (artscene, demoscene, etc.), which were doing nothing illegal, eventually branched off. The programs containing the group promotional material (coding/graphical/musical presentations) evolved to become separate programs distributed through The Scene, and were nicknamed Intros and later Cracktros.

The demoscene grew especially strong in Scandinavia, where annual gatherings are hosted.[9]

Release procedure

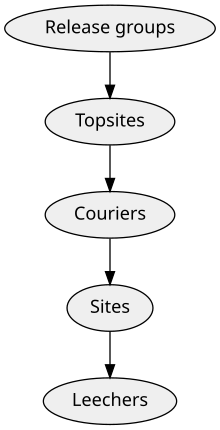

[edit]When releasing material, groups must first encode properly so as not to be nuked, which shows up as a cautionary flag to potential users. After encoding, they upload the files to a topsite, an FTP (a file transfer protocol) server with a large amount of bandwidth where all the files originate. When the upload is complete, they execute a command that causes the name and category of the release to be announced in the topsite's IRC (Internet Relay Chat) channel using an IRC bot hosting an IRC script which keeps track of activity. This FTP server and IRC are hidden and closed to the public.

New releases are also announced 0sec (meaning seconds to minutes after official scene pre) on various public websites. This is called a "pre" release. Once this is done, all other releases for the same material are nuked as duplicates ("dupes"). However, if there is a technical error or the file breaks the ruleset for the category, the original "pre" release will be nuked. Other groups then encode the same material and release it with a "PROPER" tag in the filename. The same group may re-encode the file, with the new release marked as "REPACK". If the issue was with something other than the main content, the same group can release a "fix", labelled "DIRFIX", "NFOFIX", etc. as appropriate. Release groups are exempt from FTP Share ratios in most cases, while "racers" in Topsite IRC channels will be given a ratio. Racers use FXP software and custom auto-trading software to transfer releases from one FTP to other FTP's and FTP Site-Rings (group of dedicated servers linked together) around the world. IRC site channels will use modes such as +s (secret) +p (private) and +i (invite only) to avoid detection.

Each release in The Scene consists of a folder containing the material (sometimes split into RAR pieces), plus an NFO and SFV file. The NFO is a text file which has essential information about the files encoded, including a reason for the nuke if the file is a PROPER or REPACK release. A robust NFO file may contain a group's mission statement, recruitment requirements, greetings, and contact info; many groups have a standard ASCII art template for the file, with the most prolific exhibiting elaborate artistic examples. The SFV file uses checksums to ensure that the files of a release are working properly and have not been damaged or tampered with. This is typically done with the aid of an external executable like QuickSFV or SFV Checker. Failure to include an NFO or SFV file in the release will generally result in a nuke, as these are essential components of the warez standard to which The Scene adheres.

In 2012, The Scene had over 100 active groups releasing material. Over 1,000 releases were made each day, with a cumulative total of more than five and a half million releases through 2012.[10]

As of 2023, the number of releases has doubled since 2012, surpassing 11 million in total. With now over 400 active scene release groups, more than 2,000 releases are made every day.[11]

Crackers and reverse engineers

[edit]Software cracking has been the core element of The Scene since its beginning. This part of The Scene community, sometimes referred to as the crack scene, specializes in the creation of software cracks and keygens. The challenge of software cracking and reverse engineering complicated software is what makes it an attraction.[12] The game cracking group SKIDROW described it as follows in one of their NFO files:[13]

Keep in mind we do all this, because we can and because we like the thrilling excitement of winning over the other competing groups. We absolutely don't do all these releases, to please the general user that rather want to spend their cash on updating to the latest hardware, and sees the scene releases as a source to play all these games for free. Enjoy playing and remember if you like it, support the developer!

The game ripping group MYTH expressed it as follows in their NFO files:[14]

We do this just for FUN. We are against any profit or commercialisation of piracy. We do not spread any release, others do that. In fact, we BUY all our own games with our own hard earned and worked for efforts. Which is from our own real life non-scene jobs. As we love game originals. Nothing beats a quality original. "If you like this game, BUY it. We did!"

David Grime, former DrinkOrDie member, describes the motivation of The Warez Scene as follows: "It's all about stature. They are just trying to make a name for themselves for no reason other than self-gratification."[15][16]

See also

[edit]- Copyright infringement

- Crack intro

- FXP board

- Hacker subculture

- How Music Got Free – book by Stephen Witt

- I Am... (Nas album) – one of the first major label releases to be widely leaked using MP3 technology.

- Legal aspects of file sharing

- List of warez groups

- SCA (computer virus) – first computer virus for the Commodore Amiga, created by Swiss Cracking Association[17]

- Standard (warez)

- The Scene – miniseries

- Topsite

- Twilight – pressed warez disks sold in the Netherlands in the late nineties using scene releases

References

[edit]- ^ Walleij, Linus (1998). "Chapter 5 – Subculture of the Subcultures". Copyright does not exist (PDF). Translated by Øien, Daniel A.

The Scene (capital S) is thus a label for the large group of users that exchange programs (primarily games) and also so-called demos.

- ^ Eve, Martin Paul (2021). Warez: The Infrastructure and Aesthetics of Piracy. Earth, Milky Way: punctum books. p. 21. ISBN 978-1-68571-036-1.

- ^ Crisp, Virginia (2017). Film Distribution in the Digital Age: Pirates and Professionals. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 186.

- ^ Eve, Martin Paul (2021). Warez: The Infrastructure and Aesthetics of Piracy. Earth, Milky Way: punctum books. p. 186. ISBN 978-1-68571-036-1.

- ^ a b "The History of the Warez Scene (unfinished)". Retrieved 2012-07-07.

- ^ McCandless, David (April 1997). "Warez Wars". Wired. Retrieved 2009-06-06.

- ^ "scene history". Retrieved 2009-06-06.

- ^ The BBS Documentary – MOVIE

- ^ "ASSEMBLY Summer 2011 – Finland's largest computer festival in Helsinki". 2011.

- ^ "PreDB.in". Archived from the original on 2012-01-15. Retrieved 2012-01-19.

- ^ "PreDB.net".

- ^

Craig, Paul; Honick, Ron (April 2005). "Chapter 4: Cracking". In Burnett, Mark (ed.). Software Piracy Exposed – Secrets from the Dark Side Revealed. United States of America: Syngress Publishing. p. 63. doi:10.1016/B978-193226698-6/50029-5. ISBN 1-932266-98-4.

For many, it is the challenge of the game; trying to defeat technology designed specifically to stop them. For others, there is a significant financial incentive involved. Many black market counterfeiting operations employ crackers to remove copy protection from software titles, thereby allowing the material to be copied and sold. Cracking is taken very seriously, and is the most respected role in the warez group scene.

- ^ Trainz.Simulator.12.Nfo.Fix-SKIDROW, 2011-04-18

- ^ Yager.DVDRiP-MYTH, 2003-09-25

- ^ Lee, Jennifer (2002-07-11). "Pirates on the Web, Spoils on the Street". The New York Times.

- ^ Chandra, Priyank (2016). "Order in the Warez Scene". Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems – CHI '16. pp. 372–383. doi:10.1145/2858036.2858341. ISBN 9781450333627. S2CID 15919355.

- ^ "The Movers Collection, Part 2". got papers?. 2016-01-27.

SCA sending out custom-made anti-virus software to protect their friends from their own SCA Virus

Further reading

[edit]- Crisp, Virginia (2017). Film Distribution in the Digital Age: Pirates and Professionals. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Eve, Martin Paul (2021). Warez: The Infrastructure and Aesthetics of Piracy. Earth, Milky Way: punctum books. ISBN 978-1-68571-036-1.

- Huizing, Ard; van der Wal, Jan A. (2014-10-06). "Explaining the rise and fall of the Warez MP3 scene: An empirical account from the inside". First Monday. 19 (10). doi:10.5210/fm.v19i10.5546. ISSN 1396-0466.

- Hitzler, R.; Niederbacher, A. (2010). Leben in Szenen: Formen Juveniler Vergemeinschaftung Heute [Living in Scenes. Forms of Youth Communities] (in German). VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften GmbH. ISBN 9783531925325. Retrieved 2013-06-23.

- Maher, Jimmy (2012). "Chapter 7: The Scene". The Future Was Here: The Commodore Amiga. The MIT Press. ISBN 9780262017206.

- Maher, Jimmy (2016-01-01). "A Pirate's Life for Me, Part 2: The Scene". The Digital Antiquarian.

- Rau, Lars (2004-10-22). Phänomenologie und Bekämpfung von "Cyberpiraterie": eine kriminologische und kriminalpolitische Analyse [Phenomenology and combat "cyber piracy": a criminological and criminal policy analysis] (Ph.D.) (in German). Justus-Liebig-Universität. ISBN 3-86537-246-5. Retrieved 2013-07-27.

- Sockanathan, Andrew (2011). Digital Desire and Recorded Music: OiNK, Mnemotechnics and the Private BitTorrent Architecture (Ph.D.). Goldsmiths, University of London, Centre for Cultural Studies.

- Wasiak, Patryk (2014-04-15). ""Amis and Euros." Software Import and Contacts Between European and American Cracking Scenes". WiderScreen (1–2).

- Wasiak, Patryk (2012). "'Illegal Guys'. A History of Digital Subcultures in Europe during the 1980s". Zeithistorische Forschungen/Studies in Contemporary History, Online-Ausgabe. 9 (2): 257–276.

- Stephen Witt, How Music Got Free: The End of an Industry, the Turn of the Century, and the Patient Zero of Piracy, Viking (June 16, 2015), hardcover, 304 pages, ISBN 978-0525426615

- van der Wal, Jan Adriaan (2009). The "rise" and "fall" of the MP3scene: A Global and Virtual Organization - An organizational, social relational and technological analysis (Thesis).

- Martin Paul Eve (2021-12-14). Warez: The Infrastructure and Aesthetics of Piracy. Punctum Books. doi:10.53288/0339.1.00. ISBN 978-1-68571-036-1. OL 35740478M. S2CID 245239564.

External links

[edit]- Scene history in video on YouTube

- The Recollection Magazine – Recollections of the early scene.

- Ultimate C64 Scene Mag Archive – Collection of C64 disk and paper magazines.

- Scenet FAQ – What kind of creation/building/element/organisation is the SCENE?

- Warez Warz – 04/01/1997 Article detailing some major scene events in 1996 and the scene in general. Includes interviews.