Saved from the Titanic

| Saved from the Titanic | |

|---|---|

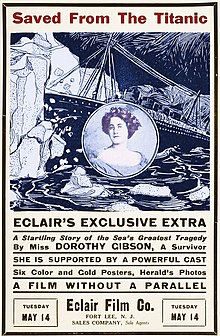

Retinted 1912 advertisement of film | |

| Directed by | Étienne Arnaud |

| Starring |

|

| Distributed by | Eclair Film Company |

Release date |

|

Running time | 10 min. (300 m) |

| Country | United States |

| Language | Silent (English Intertitles) |

Saved from the Titanic was a 1912 American silent short film starring Dorothy Gibson, an American film actress who survived the sinking of the RMS Titanic on April 15, 1912. Premiering in the United States just 31 days after the event, it was the earliest dramatization of the tragedy.[1]

Gibson had been one of 28 people aboard the first lifeboat to be launched from Titanic and was rescued about five and a half hours after leaving the ship. On returning to New York City, she co-wrote the script and played a fictionalized version of herself. The plot involves her recounting the story of the disaster to her fictional parents and fiancé, with the footage interspersed with stock footage of icebergs, Titanic's sister ship Olympic and the ship's captain, Edward Smith. To add to the film's authenticity, Gibson wore the same clothes as on the night of the disaster. The filming took place in a Fort Lee, New Jersey studio and aboard a derelict ship in New York Harbor.

The film was released internationally and attracted large audiences and positive reviews, though some criticized it for commercializing the tragedy so soon after the event. It is now regarded as a lost film,[1] as the last known prints were destroyed in the Éclair studio fire in March 1914. Only a few printed stills and promotional photos are known to survive. It is Gibson's final film, as she reportedly suffered a mental breakdown after completing it.[2]

Gibson's voyage on the Titanic

[edit]The 22-year-old Gibson was a passenger aboard Titanic's maiden voyage, joining the ship at Cherbourg in France on the evening of April 10. She had been on vacation in Europe with her mother when her employers, the Eclair Film Company, recalled her to New York City to participate in a new production. On the evening of the sinking, she was playing bridge (this would have been bridge whist, a predecessor to today's game) in a first-class saloon before retiring to the cabin that she shared with her mother.[3][4] The game was later credited with saving the lives of the players who had stayed up late to finish it, despite it being (as one American writer put it) "a violation of the strict Sabbath rules of English vessels."[4] The collision with the iceberg at 11:40 pm sounded to Gibson like a "long, drawn, sickening scrunch". After going to investigate, she fetched her mother when she saw Titanic's deck beginning to list as water flooded into the ship's boiler rooms.[3]

Two of the bridge players, Frederic Seward and William Sloper, accompanied Gibson and her mother to the lifeboats.[5] The group boarded lifeboat no. 7, the first to be launched.[6] Around 27 other people were on board the boat when it was lowered at 12:40 am, just over an hour after the collision.[7] The lifeboat's plug could not be found, causing water to gush in until, as Gibson later put it, "this was remedied by volunteer contributions from the lingerie of the women and the garments of men."[3] Around 1,500 people were still aboard Titanic when she sank, throwing them into freezing water where they soon died of hypothermia. As they struggled in the water, Gibson heard what she described as a "terrible cry that rang out from people who were thrown into the sea and others who were afraid for their loved ones."[3] The sinking deeply affected her; according to Sloper, she became "quite hysterical and kept repeating over and over so that people near us could hear her, 'I'll never ride in my little grey car again.'"[8] The occupants of the lifeboat were finally rescued at 6:15 am by the RMS Carpathia and taken to New York.[9]

Production

[edit]

Only a few days after she returned to New York, Gibson began work on a film based on the disaster. The impetus may have come from Jules Brulatour, an Éclair Film Company producer with whom she was having an affair. According to Billboard magazine he sent "specially chartered tugboats and an extra relay of cameramen" to film the arrival of Carpathia. The footage was spliced together with other scenes such as Titanic's Captain Edward Smith on the bridge of the RMS Olympic, Titanic's sister ship, images of the launch of Titanic in 1911 and stock footage of icebergs. On April 22, the resulting newsreel was released as part of the studio's Animated Weekly series.[10] It was an enormous success with sold-out showings across America. President William Howard Taft, whose friend and military aide Archibald Butt was among the victims of the disaster, received a personal copy of the film.[11]

The success of the newsreel appears to have convinced Brulatour to capitalize further with a drama based on the sinking. He had a unique advantage – a leading actress who was a survivor and eyewitness to what had happened. Gibson later described her decision to participate as an "opportunity to pay tribute to those who gave their lives on that awful night."[12] Jeffrey Richards suggests that it was more likely that Brulatour persuaded her that the disaster offered an opportunity to advance her career.[13] The filming took place at Éclair's studio in Fort Lee, New Jersey[14] and aboard a derelict transport vessel in New York Harbor.[13] It was completed in only a week and the entire process of filming, processing and distribution took only half the time normally required for a one-reel film – a sign of the producers' eagerness to get the film onto screens while news of the disaster was still fresh.[15] The film was only ten minutes long[6] but this was typical of the time, as feature films had not yet become the norm. Instead, a program typically consisted of six to eight short films, each between ten and fifteen minutes long and covering a range of genres. Although newsreels were the main vehicle for presenting current events, dramas and comedies also picked up on such issues. There was very little footage of Titanic herself, which hindered the ability of newsreels to depict the sinking; however, the disaster was an obvious subject for a drama.[16]

Gibson was plainly still traumatized – a reporter from the Motion Picture News described her as having "the appearance of one whose nerves had been greatly shocked" – and she was said to have burst into tears during filming. To add to the film's air of authenticity, she even wore the same clothes that she was rescued in.[3] Nonetheless, as well as starring as "Miss Dorothy" – herself, in effect – Gibson is said to have co-written the script, which was based on a fictionalized version of her own experiences. Her parents and (fictional) fiancé, Ensign Jack, are shown waiting anxiously for her return after hearing news of the disaster. She arrives safely back home and recounts the events of the disaster in a long flashback, illustrated with newsreel footage of Titanic and a mockup of the collision itself. Titanic sinks but Dorothy is saved. When she concludes her story, her mother urges Dorothy's fiancé to leave the navy as it is too dangerous a career. Jack ultimately rejects the mother's advice, deciding that he must do his duty for his flag and his country. Dorothy's father is moved by his patriotism and the film ends with him blessing their marriage.[17]

The film's structure aimed to promote its story's authenticity and credibility through the integration of newsreel footage and the presence of a genuine survivor as the "narrator". Audiences had previously seen survivors of disasters only as unspeaking "objects" shown as part of a story told by someone else. Gibson, by contrast, was a survivor given voice as the narrator of what was ostensibly her personal story.[18]

Release and reception

[edit]

Saved from the Titanic was released in the United States on May 16, 1912 [19] and was also released internationally, in the United Kingdom as A Survivor of the Titanic[20] and in Germany as Was die Titanic sie lehrte ("What the Titanic Taught Her").[21] It attracted a positive review in The Moving Picture World of May 11, 1912, which described Gibson's performance as "a unique piece of acting in the sensational new film-play of the Éclair Company ... [which is] creating a great activity in the market, for the universal interest in the catastrophe has made a national demand."[22] The review went on:

Miss Gibson had hardly recovered from her terrible strain in the wreck, when she was called upon to take part in this new piece, which she constructed as well. It was a nerve-racking task, but like actresses before the footlights, this beautiful young cinematic star valiantly conquered her own feelings and went through the work. A surprising and artistically perfect reel has resulted.[22]

The Motion Picture News commended the film's "wonderful mechanical and lighting effects, realistic scenes, perfect reproduction of the true history of the fateful trip, magnificently acted. A heart-stirring tale of the sea's greatest tragedy depicted by an eye-witness." However, some criticized the questionable tastefulness of portraying a disaster that had so recently occurred. "Spectator" in the New York Dramatic Mirror condemned the venture as "revolting":

The bare idea of undertaking to reproduce in a studio, no matter how well equipped, or by re-enacted sea scenes an event of the appalling character of the Titanic disaster, with its 1,600 victims, is revolting, especially at this time when the horrors of the event are so fresh in mind. And that a young woman who came so lately, with her good mother, safely through the distressing scenes can now bring herself to commercialize her good fortune by the grace of God, is past understanding ... [23]

Fate

[edit]Saved from the Titanic is now considered a lost film, as the only known prints were destroyed in a fire at the Fort Lee, New Jersey studio of the Éclair Moving Picture Company in March 1914. Its only surviving visual records are a few production stills, printed in the Moving Picture News and Motion Picture World, showing scenes of the family and a still of Dorothy standing in front of a map of the North Atlantic pointing to the location of the Titanic.[23] Frank Thompson highlights the film as one of a number of "important movies that disappeared", noting that it was unique for having "an actual survivor of the Titanic playing herself in a film" while wearing "the very clothes ... in which she abandoned ship":

[T]hat all this was committed to film within days of the disaster is enough to make any Titanic enthusiast sigh with frustration. No matter what melodramatic hocum found its way into the film – and the synopsis suggests that there was plenty – Saved from the Titanic is an irreplaceable piece of Titanic lore.[24]

It was also Dorothy Gibson's last film, as the effort of making it appears to have brought on an existential crisis for her. According to a report in the Harrisburg Leader, "she had practically lost her reason, by virtue of the terrible strain she had been under to graphically portray her part."[25]

Cast

[edit]- Dorothy Gibson as Miss Dorothy

- Alec B. Francis as Father

- Julia Stuart as Mother

- John G. Adolfi as Ensign Jack

- William R. Dunn as Jack's pal

- Guy Oliver as Jack's pal[26]

See also

[edit]- In Nacht und Eis (1912), the second film about the disaster

- List of lost films

- List of films about the RMS Titanic

- "La hantise" (1912), the third film about the disaster

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ a b Thompson, Frank (March 2, 1998). "'Saved': The Real First Titanic Movie". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ S, Lea (April 27, 2015). "Lost Films: Saved From The Titanic (1912)". Silent-ology. Retrieved March 2, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Bottomore 2000, p. 109.

- ^ a b Mowbray 1912, p. 32.

- ^ Davenport-Hines 2012.

- ^ a b Spignesi 2012, p. 267.

- ^ Wormstedt & Fitch 2011, p. 137.

- ^ Wilson 2011, p. 255.

- ^ Wormstedt & Fitch 2011, pp. 137, 144.

- ^ Wilson 2011, p. 259.

- ^ Wilson 2011, p. 260.

- ^ Wilson 2011, p. 261.

- ^ a b Richards 2003, p. 11.

- ^ Wilson 2011, p. 262.

- ^ Shapiro 1998, p. 119.

- ^ Bottomore 2000, pp. 106–7.

- ^ Bottomore 2000, p. 111.

- ^ Wedel 2004, p. 99.

- ^ Leavy 2007, p. 153.

- ^ Howells 1999.

- ^ Wedel 2004, p. 98.

- ^ a b Koszarski 2004, p. 106.

- ^ a b Bottomore 2000, p. 114.

- ^ Thompson 1996, p. 18.

- ^ Wilson 2011, p. 247.

- ^ Thompson 1996, p. 12.

References

[edit]- Bottomore, Stephen (2000). The Titanic and Silent Cinema. Hastings, UK: The Projection Box. ISBN 978-1-903000-00-7.

- Davenport-Hines, Richard (2012). Titanic Lives: Migrants and Millionaires, Conmen and Crew. London: HarperCollins UK. ISBN 978-0-00-732165-0.

- Howells, Richard (1999). The Myth of the Titanic. United Kingdom: MacMillan Press. ISBN 978-0-333-72597-9.

- Koszarski, Richard (2004). Fort Lee: The Film Town. Rome, Italy: John Libbey Publishing. ISBN 978-0-86196-653-0.

- Leavy, Patricia (2007). Iconic Events: Media, Politics, and Power in Retelling History. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-1520-6.

- Mowbray, Jay Henry (1912). Sinking of the Titanic. Harrisburg, PA: The Minter Company. OCLC 9176732.

- Richards, Jeffrey (2003). A Night to Remember: The Definitive Titanic Film. London: I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-86064-849-6.

- Shapiro, Marc (1998). Total Titanic. New York: Byron Preiss. ISBN 978-0-671-01202-1.

- Spignesi, Stephen J. (2012). The Titanic For Dummies. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-20651-5.

- Wedel, Michael (2004). "Early German Cinema and the Modern Media Event". In Bergfelder, Tim; Street, Sarah (eds.). The Titanic in Myth and Memory : Representations in Visual and Literary Culture. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-0-7524-6210-3.

- Thompson, Frank (1996). Lost Films: Important Movies That Disappeared. New York: Carol Publishing Group. ISBN 9780806516042.

- Wilson, Andrew (2011). Shadow of the Titanic. London: Simon & Schuster Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84737-730-2.

- Wormstedt, Bill; Fitch, Tad (2011). "An Account of the Saving of Those on Board". In Halpern, Samuel (ed.). Report into the Loss of the SS Titanic: A Centennial Reappraisal. Stroud, UK: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-6210-3.

External links

[edit]