Blockade of Yemen

The blockade of Yemen refers to a sea, land and air blockade on Yemen which started with the positioning of Saudi Arabian warships in Yemeni waters in 2015 with the Saudi Arabian-led intervention in Yemen. In November 2017, after a Houthi missile heading towards King Khalid International Airport was intercepted,[1] the Saudi-led military coalition stated it would close all sea land and air ports to Yemen,[2] but shortly began reopening them after criticism from the United Nations and over 20 aid groups[3] and some humanitarian supplies were allowed into the country.[4] In March 2021, Saudi Arabia denied the blockade continued, however, UN authorized ships continued to be delayed by Saudi warships.[5]

The blockade has contributed to the current famine in Yemen, which the United Nations said may become the deadliest famine in decades.[6][7] The World Health Organization announced in 2017, that the number of suspected persons with cholera in Yemen reached approximately 500,000 people.[8][9] In 2018, Save the Children estimated that 85,000 children have died due to starvation in the three years prior.[10][11]

Background

[edit]A military intervention was launched by Saudi Arabia in March 2015, which was leading a coalition of nine countries from the Middle East and Africa, in order to influence the outcome of the Yemeni civil war in favor of President Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi’s government.[12] The intervention code-named "Operation Decisive Storm" included a bombing campaign and subsequently saw a naval blockade and likewise deploying ground forces in Yemen.[13] As a result of that, there have been many innocent women and children killed, as well as Houthi fighters.[14][15]

Effects and supply shortage

[edit]

As a result of the blockade, there is a desperate shortage of necessary supplies such as food, water and medical supplies, to the extent that children are at risk of disease due to lack of drinkable water.[16]

A limited number of aid ships can unload, and the bulk of commercial shipping, on which the desperately poor country depends, is being blocked, creating a state of emergency for Yemenis.[17][18] In spite of entreaties, Saudi Arabia has failed to pay out any of the $274 million it promised to invest into humanitarian relief.[19][20]

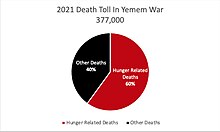

The UN estimated that by the end of 2021, the conflict in Yemen had claimed more than 377,000 lives, with 60% of them died due to issues associated with the conflict, such as starvation and preventable diseases.[21][22] In March 2022, more than 17 million people in Yemen were experiencing high levels of acute food insecurity.[23]

Impact on health

[edit]According to The Guardian, The blockade of Yemen by the Saudi-led coalition has caused medical supplies, food, and fuel to run low, doctors and aid organizations said.[25] Aditya Sarkar argues, that the blockade and military air attacks were a war tactic that aims to control food and control citizens.[26] The Hudaydah port was importing eighty percent of their food, other medical supplies and items necessary for survival.[26] Due to this, the Saudi-led coalition focused their attacks on this port.[26]

United States's role

[edit]The U.S. has supported the Arab coalition's intervention in the war, and the United States Navy actively participated in the naval blockade at the beginning of the intervention.[27][28][29] In mid-2015, Washington increased its logistical and intelligence support to Saudi Arabia by creating a joint coordination planning cell with the Saudi military to help manage the war.[30][31]

However, in mid-2016 and amid escalating, international concerns regarding some of the strategic initiatives undertaken by the Saudi Arabian military in the conflict, the U.S. pulled back significantly on its participation in this joint planning cell, reducing its staff commitment to only five US workers.[32] Saudi Arabia, reportedly relied on U.S. intelligence reports and surveillance images for airstrike target selection, some of which were against weapons and aircraft. The U.S. dispatched warships in the region after Houthi missiles targeted the UAE-operated HSV-2 Swift, which some critics interpreted as the U.S. reinforcing the coalition blockade.[33] According to Iranian sources, it has refueled Saudi planes, sent the Saudi military targeting intelligence, and resupplied them with tens of billions of dollars worth of bombs.[17][31]

U.S. President Donald Trump asked Saudi Arabia to allow humanitarian aid to enter Yemen in 2017.[34][35] In 2019, The United States Congress pushed to cease the sale of arms to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates to address the famine in Yemen, but this was ultimately vetoed by the Trump Administration on three occasions.[36]

The U.S. (and the UK) support the effort through arms sales and technical assistance. Amnesty International urged the U.S. and the UK to stop supplying arms to Saudi Arabia and to the Saudi-led coalition.[37][38][36]

It has been reported[by whom?] that the U.S. is regarded as an indirect partner for Saudi Arabia in the war and blockade on Yemen.[39] According to a 2021 article in The Washington Post, the end of the United States support for the Saudi-led blockade against Yemen could create hope for millions of Yemenis. The article states that Biden and Congress have taken no real action to end support for the coalition after declaring that he would end "all American support for offensive operations in the war in Yemen, including relevant arms sales."[40]

In September 2019, a report by UN investigators team, commissioned by the United Nations Human Rights Council claimed that the United States, Britain, and France, are probably complicit in the war in Yemen due to persisted sales of weaponry and intelligence support to the Saudis and their allies, particularly the United Arab Emirates.[41] According to this report, the U.S. role in the Yemen war moves beyond supplying training and intelligence support and sales of billions of dollars of weaponry to the UAE and Saudi Arabia, America's largest weapons buyers.[41]

United Kingdom's role

[edit]Although the United Kingdom has called on Saudi Arabia to ease the siege on Yemen and the British government allocated 4 million pounds in aid to meet emergency requirements,[42][43] the UK government has officially supported the Saudi-led coalition since the beginning of the conflict.[44]

In 2015, the then Foreign Secretary, the Rt Hon Philip Hammond MP, confirmed that the Saudis were using UK-manufactured aircraft and weaponry in Yemen and set out the extent of UK support for Saudi Arabia: "We have a significant infrastructure supporting the Saudi air force generally and if we are requested to provide them with enhanced support—spare parts, maintenance, technical advice, resupply—we will seek to do so. We’ll support the Saudis in every practical way short of engaging in combat."[45]

In 2018, UN experts called on the UK government to stop giving Saudi Arabia bombs to use in Yemen.[46][47]

In a 2019 Guardian article titled: "The Saudis couldn’t do it without us: the UK's true role in Yemen's deadly war",[48] Journalist Arron Merat explains: "Every day Yemen is hit by British bombs – dropped by British planes that are flown by British-trained pilots and maintained and prepared inside Saudi Arabia by thousands of British contractors."

Merat makes it clear that: "Britain does not merely supply weapons for this war: it provides the personnel and expertise required to keep the war going. The British government has deployed RAF personnel to work as engineers, and to train Saudi pilots and targeteers – while an even larger role is played by BAE Systems, Britain’s biggest arms company, which the government has subcontracted to provide weapons, maintenance and engineers inside Saudi Arabia."[48]

In 2019, a Channel 4 documentary film named: "Britain's Hidden War: Channel 4 Dispatches", a former BAE Systems worker revealed that the Royal Saudi Air Force (RSAF) would be unable to fly its fleet of Typhoon fighter jets without BAE's support; the former BAE worker explained: "With the amount of aircraft they’ve got and the operational demands, if we weren’t there in 7 to 14 days there wouldn’t be a jet in the sky."[49]

According to the report of UN experts and the world's most valued NGOs documenting a consistent pattern of violations, the UK is responsible for international law violations as the leading arms provider of the Saudi Arabia-led.[50]

United Nations reaction

[edit]According to Agence France-Presse, The United Nations called the Saudi-led coalition to instantly/completely lift the blockade on Yemen. The World Health Organization announced that there is a rapid incidence of diphtheria disease in 13 provinces of Yemen. This organization also added, the incidence of diphtheria in Yemen is regarded as a worrying problem.[51] The Saudi Arabian-led coalition blocked all sea, land and air borders of Yemen after Ansar Allah's missile attack on Riyadh on 6 November 2017, and did not allow international aid to be delivered to Yemeni people.[52]

According to Iranian reports, there are approximately one million Yemenis who have been affected by cholera, and more than 2200 people have died due to the disease.[51] This has led to protests against the blockade where the United Nations appealed to the Saudi Arabian-led military coalition to entirely lift its blockade of Yemen, saying up to 8 million people were "right on the brink of famine".[52]

Port blockade

[edit]

Although Saudi Arabia pledged on 20 December 2017 to lift the blockade for a month,[53] there is no reported aid or commerce coming in Yemen via the port of Hudaydah which is considered as a key port in Yemen.[citation needed] After Houthi fighters fired a missile at the capital of Saudi Arabia on 4 November 2017, Saudis sealed sea, air and land access to Yemen. Saudi officials did consent that they will lift the blockade of Hudaydah for a period of time. In the meanwhile, Riyadh mentioned that "The port of Hudaydah will remain open for humanitarian and relief supplies and the entry of commercial vessels, including fuel and food vessels, for a period of 30 days". Two weeks later, after Saudi Arabia's declaration, Hudaydah stayed empty. There are no relief vessels or traders to be seen anchored there. The manager of the port substantiated that the sea-hub did process merely two vessels whose permits were old.[54]

The port blockade also impacted Yemen's famine; because before the war, Hudaydah Port, was how Yemen would receive eighty-percent of their food.[36]

Houthi movement response

[edit]

Abdul-Malik al-Houthi as the leader of Yemen's Ansar Allah (Houthi) movement has vowed retaliatory attacks in reaction to the blockade. Recently, al-Houthi protested against “tightening the blockade” by addressing the adherents of Houthis through television. Since, Saudi Arabia has imposed a hard blockade on about all the air, sea ports and land of Yemen after Yemenis launched a solid propellant and scud-type missile against the international airport of King Khalid which is located thirty-five kilometers north of Riyadh as the capital of Saudi, in reaction to Saudi Arabia's devastating aerial bombardment campaign over Yemenis. Abdul-Malik al-Houthi declared that they are aware that what (targets) could cause big trouble and of course how to reach them.[55]

The leader of Ansar Allah emphasized that Saudi Arabia and UAE are within range of the missiles, and Yemeni's UAVs will begin bombing the targets over Saudi Arabia. Abdul-Malik al-Houthi also warned the companies and investors who are in UAE that all companies in UAE ought not to consider United Arab Emirates as a safe country from now on. He also said to invaders that they ought not to commit aggression to Al-Hudaydah if they want to protect their oil tankers.[56]

Legal background

[edit]According to the international law of naval blockade the naval measures conducted by the coalition led by Saudi Arabia do not amount to a naval blockade in the legal sense.[57] It is said that neither the international law of contraband nor the United Nations Security Council Resolution 2216 of 14 April 2015 cover the extensive enforcement measures.[58] Due to the devastating famine in Yemen and supply shortage of essential goods, which are caused by the enforcement measures, the naval operations off the coast of Yemen are criticized as a violation of international humanitarian law.[59]

See also

[edit]- Outline of the Yemeni Crisis, revolution, and civil war (2011-present)

- 2016–2022 Yemen cholera outbreak

- Airstrikes on Yemen

- Water supply and sanitation in Yemen

References

[edit]- ^ "Saudi Arabia: Missile intercepted near Riyadh". BBC News Services. 4 November 2017. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- ^ Westall, Sylvia; Nichols, Michelle; et al. (Reuters' Dubai newsroom) (5 November 2017). Kerry, Frances; Grebler, Dan; Peter, Peter (eds.). "Saudi-led forces close air, sea and land access to Yemen". Reuters. Dubai. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ^ al-Haj, Ahmed (13 November 2017). "Yemen rebels vow escalation as Saudis look to relax blockade". Associated Press News. Sanaa. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ^ Erickson, Amanda (1 December 2017). "Saudi Arabia lifted its blockade of Yemen. It's not nearly enough to prevent a famine". Washington Post. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- ^ Emmons, Alex. "MONTHS AFTER BIDEN PROMISED TO END SUPPORT FOR YEMEN WAR, CONGRESS STILL HAS NO DETAILS". Intercept. Retrieved 9 September 2021.

- ^ "Yemen conflict: UN official warns of world's biggest famine". BBC News. 9 November 2017. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ^ "Employee of the Month: Mohamed bin Salman". Reinventing Peace. 7 December 2017. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ^ Aleem, Zeeshan (22 November 2017). "Saudi Arabia's new blockade is starving Yemen". Vox. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ^ "Millions of people live in Yemen and their country نیم میلیون نفر در یمن وبا گرفتهاند" [A half million people in Yemen have been affected by Cholera]. BBC News فارسی (in Persian). Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ^ Karasz, Palko (21 November 2018). "85,000 Children in Yemen May Have Died of Starvation". The New York Times.

- ^ Merchan, Davi; Davies, Guy (23 November 2018). "85,000 children in Yemen have starved to death: Save the Children report". ABC News.

- ^ Almeida, Alex; Knights, Michael (25 March 2016). "Gulf Coalition Operations in Yemen (Part 1): The Ground War". The Washington Institute. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ^ "Mohammed bin Salman's ill-advised ventures have weakened Saudi Arabia's position in the world". en.alalam.ir. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ^ "ادامه جنایات عربستان در یمن با كشته شدن 7 زن و كودك در استان صعده" [Continuation of Saudi Arabia in Yemen]. www.irna.ir (in Persian). Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ^ Gatten, Emma (19 September 2015). "Saudi blockade starves Yemen of vital supplies, as bombing continues". The Independent. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ^ Ratcliffe, Rebecca (30 August 2017). "Yemen conflict: human rights groups urge inquiry into Saudi coalition abuses". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ^ a b Borger, Julian (23 December 2017). "Saudi-led naval blockade leaves 20m Yemenis facing humanitarian disaster". The Guardian.

- ^ Almosawa, Shuaib (16 March 2022). "As U.S. Focuses on Ukraine, Yemen Starves". The Intercept.

- ^ "Saudi blockade leaves 20mn Yemeni in crisis". World Bulletin. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ^ Saudi Arabia fatally bombs ANOTHER Yemeni hospital + 18 Billion in US weapons + Bowie democraticunderground.org Retrieved 7 January 2018

- ^ "Yemen war deaths will reach 377,000 by end of the year: UN". Al Jazeera. 23 November 2021.

- ^ "Yemen: Why is the war there getting more violent?". BBC News. 22 March 2022.

- ^ "Yemen facing 'outright catastrophe' over rising hunger, warn UN humanitarians". UN News. 14 March 2022.

- ^ "Yemen war deaths will reach 377,000 by end of the year: UN". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 27 September 2023.

- ^ al-Mujahed, Ali; Naylor, Hugh (2 June 2015). "Yemen conflict: doctors warn of crisis as medical supplies run low". The Guardian.

- ^ a b c Sarkar, Aditya (30 September 2022), Conley, Bridget; de Waal, Alex; Murdoch, Catriona; Jordash QC, Wayne (eds.), "'Once We Control Them, We Will Feed Them': Mass Starvation in Yemen", Accountability for Mass Starvation (1 ed.), Oxford University PressOxford, pp. 217–C9.N181, doi:10.1093/oso/9780192864734.003.0009, ISBN 978-0-19-286473-4, retrieved 5 October 2023

- ^ Brook, Tom Vanden. "U.S. carrier moving off coast of Yemen to block Iranian arms shipments". USA TODAY. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ^ Sheline, Annelle R.; Riedel, Bruce (16 September 2021). "Biden's broken promise on Yemen". Brookings Institution.

- ^ McKernan, Bethan (7 November 2018). "Battle rages in Yemen's vital port as showdown looms". The Guardian.

The port has been blockaded by the Saudi-led coalition for the past three years, a decision aid organizations say has been the main contributing factor to the famine that threatens to engulf half of Yemen's 28 million population.

- ^ Hosenball, Mark; Stewart, Phil; Strobel, Warren (10 April 2015). Grudgings, Stuart (ed.). "Exclusive: U.S. expands intelligence sharing with Saudis in Yemen operation". Reuters. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ^ a b Almasy, Steve; Hanna, Jason (13 January 2018). "Saudi Arabia launches airstrikes in Yemen". CNN.

- ^ Stewart, Phil (19 August 2016). "Exclusive: U.S. withdraws staff from Saudi Arabia dedicated to Yemen planning". Reuters. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ^ Emmons, Alex (21 November 2017). "In Yemen's "60 Minutes" Moment, No Mention That the U.S. Is Fueling the Conflict". The Intercept. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ^ Holland, Steve; Stewart, Phil (6 December 2017). "Trump asks Saudi Arabia to allow immediate aid to Yemen". Reuters. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ^ "درخواست ترامپ از عربستان سعودی درباره یمن - اخبار تسنیم" [The request of Trump from KSA about Yemen]. Tasnim (in Persian). Retrieved 31 December 2017.

- ^ a b c Runge, Carlisle Ford; Graham, Linnea (1 April 2020). "Viewpoint: Hunger as a weapon of war: Hitler's Hunger Plan, Native American resettlement and starvation in Yemen". Food Policy. 92: 101835. doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2020.101835. ISSN 0306-9192.

- ^ Gatehouse, Gabriel (11 September 2015). "Inside Yemen's forgotten war". BBC News. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ^ Sandhu, Serina (8 October 2015). "Amnesty International urges Britain to stop supplying arms to Saudi Arabia". The Independent. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ^ Hanna, Steve Almasy,Jason (25 March 2015). "Saudi Arabia launches airstrikes in Yemen". CNN. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Saleh, Iman (9 April 2021). "I'm on hunger strike until the U.S. ends all support for the Saudi-led blockade against Yemen". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 8 April 2021.

- ^ a b Bazzi, Mohamad (3 October 2019). "America is likely complicit in war crimes in Yemen. It's time to hold the US to account". The Guardian.

- ^ Loveluck, Louisa (11 September 2015). "Britain 'fuelling war in Yemen' through arms sales, says charity". The Telegraph. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ^ "Theresa May: Saudi blockade on Yemen must be eased". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ^ Foster, Peter (27 March 2015). "UK 'will support Saudi-led assault on Yemeni rebels - but not engaging in combat'". The Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- ^ "House of Commons - The use of UK-manufactured arms in Yemen - Foreign Affairs Committee". publications.parliament.uk. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ Sanchez, Raf (28 August 2018). "UN experts call on UK to stop giving Saudi Arabia bombs to use in Yemen". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 13 January 2024.

- ^ "Situation of human rights in Yemen, including violations and abuses since September 2014 (A/HRC/39/43) (Advance edited version) [EN\AR] - Yemen | ReliefWeb". reliefweb.int. 28 August 2018. Retrieved 13 January 2024.

- ^ a b Merat, Arron (18 June 2019). "'The Saudis couldn't do it without us': the UK's true role in Yemen's deadly war". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- ^ "Britain's Hidden War: Channel 4 Dispatches". Channel 4. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- ^ Wearing, David Wearing (6 September 2019). "Britain is behind the slaughter in Yemen. Here's how you could help end it". The Guardian.

- ^ a b "United Nations calls for complete lifting of Saudi blockade". tasnimnews.com. 11 January 2018.

- ^ a b Miles, Tom (31 December 2017). Jones, Gareth (ed.). "United Nations calls for complete lifting of Saudi blockade". Reuters.

- ^ No Ships in Yemen's Key Port Despite Saudi Arabia Claim of Lifting Blockade Archived 2018-01-08 at the Wayback Machine en.farsnews.com Retrieved 7 January 2018

- ^ NO SHIPS IN YEMEN’S KEY PORT DESPITE SAUDI CLAIM OF LIFTING BLOCKADE Archived 2018-01-07 at the Wayback Machine yemenpress.org Retrieved 7 January 2018

- ^ "Saudi Arabia 'intercepts another Houthi missile'". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ^ Al-Houthi: Abu Dhabi and Riyadh are within range of Yemini missiles / the flight of UAVs over Saudi tasnimnews.com Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- ^ Fink, Martin D. (1 July 2017). "Naval Blockade and the Humanitarian Crisis in Yemen". Netherlands International Law Review. 64 (2): 291–307. doi:10.1007/s40802-017-0092-3. hdl:11245.1/bf2c3102-23de-4cbc-b4ff-9009276b5569. ISSN 0165-070X.

- ^ Daum, Oliver. "War in Yemen (1): Why the Saudi-led coalition's blockade is not a naval blockade". www.juwiss.de. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- ^ Daum, Oliver. "War in Yemen (2): Why the Saudi-led coalition has not obeyed the law of naval blockade and violates IHL". www.juwiss.de. Retrieved 28 May 2018.