San Remo conference

| San Remo resolution | |

|---|---|

After the resolution on 25 April 1920, standing outside Villa Devachan, from left to right: Matsui, Lloyd George, Curzon, Berthelot, Millerand, Vittorio Scialoja, Nitti | |

| Created | 25 April 1920 |

| Author(s) | Lloyd George, Millerand, Nitti and Matsui |

| Purpose | Allocating the Class "A" League of Nations mandates for the administration of three then-undefined Ottoman territories in the Middle East: "Palestine", "Syria" and "Mesopotamia" |

| Paris Peace Conference |

|---|

|

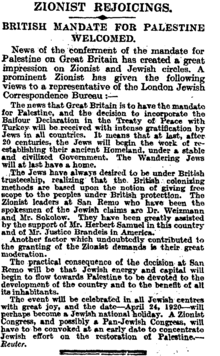

The San Remo conference was an international meeting of the post-World War I Allied Supreme Council as an outgrowth of the Paris Peace Conference, held at Castle Devachan in Sanremo, Italy, from 19 to 26 April 1920. The San Remo Resolution passed on 25 April 1920 determined the allocation of Class "A" League of Nations mandates for the administration of three then-undefined Ottoman territories in the Middle East: "Palestine", "Syria" and "Mesopotamia". The boundaries of the three territories were "to be determined [at a later date] by the Principal Allied Powers", leaving the status of outlying areas such as Zor and Transjordan unclear.

The conference was attended by the four Principal Allied Powers of World War I who were represented by the prime ministers of Britain (David Lloyd George), France (Alexandre Millerand), Italy (Francesco Nitti) and by Japan's Ambassador Keishirō Matsui.

Prior events

It was convened following the February Conference of London where the allies met to discuss the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire and the negotiation of agreements that would become the Treaty of Sèvres.

On 30 September 1918 supporters of the Arab Revolt in Damascus had declared a government loyal to Sharif Hussein, who had been declared "King of the Arabs" by religious leaders and other notables in Mecca.[1] During the meetings of the Council of Four in 1919, British Prime Minister Lloyd George stated that the McMahon–Hussein Correspondence was the basis for the Sykes–Picot Agreement, which proposed an independent Arab state or confederation of states.[2] In July 1919 the parliament of Greater Syria had refused to acknowledge any right claimed by the French Government to any part of Syrian territory.[3]

On 6 January 1920 Hussein's son Prince Faisal initialled an agreement with French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau which acknowledged "the right of the Syrians to unite to govern themselves as an independent nation".[4] A Pan-Syrian Congress, meeting in Damascus, had proclaimed an independent Arab Kingdom of Syria on 8 March 1920.[5] The new state included modern Syria and Jordan, portions of northern Mesopotamia which had been set aside under the Sykes–Picot Agreement for an independent Arab state or confederation of states, and nominally the areas of modern Israel–Palestine and Lebanon, although the latter areas were never under Faisal's control. Faisal was declared the head of state. At the same time Prince Zeid, Faisal's brother, was declared regent of Mesopotamia.

Attendees

The conference was attended by the allies, the US representative joining the meeting later in an observer capacity:[6]

British Empire:

- David Lloyd George, Prime Minister

- Lord Curzon, Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs

- Robert Vansittart

- Colonel Walter H. Gribbon

- Secretaries: Maurice Hankey, Lieutenant-Colonel L. Storr

France:

- Alexandre Millerand, President of the French Council of Ministers

- Philippe Berthelot

- Albert Kammerer

Italy:

- Francesco Saverio Nitti, Prime Minister (in the Chair)

- Vittorio Scialoja

- Secretaries: Signor Garbasso, Signor Galli, Signor Trombetti, Lieutenant Zanchi.

Japan:

- Matsui Keishirō

- Secretaries: Mr. Saito, Mr. Sawada.

Interpreter:

- Gustave Henri Camerlynck

United States of America (as observers):

- Robert Underwood Johnson, US Ambassador in Rome

- Leland Harrison

- T. Hart Anderson, Jr.

Issues addressed

The peace treaty with Turkey, the granting of League of Nation mandates in the Middle East, Germany's obligations under the Versailles Peace Treaty of 1919, and the Allies' position on Soviet Russia.[7]

Agreements reached

Asserting that not all parts of the Middle East were ready for full independence, mandates were established for the government of three territories: Syria, Mesopotamia and Palestine. In each case, one of the Allied Powers was assigned to implement the mandate until the territories in question could "stand alone." Great Britain and France agreed to recognize the provisional independence of Syria and Mesopotamia, while claiming mandates for their administration. Palestine was included within the Ottoman administrative districts of the Mutasarrifate of Jerusalem together with the Sanjak of Nablus and Sanjak of Akka (Acre).[8][9][10]

The decisions of the San Remo conference confirmed the mandate allocations of the Conference of London. The San Remo Resolution adopted on 25 April 1920 incorporated the Balfour Declaration of 1917. It and Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations were the basic documents upon which the British Mandate for Palestine was constructed. Under the Balfour Declaration, the British government had undertaken to favour the establishment of a national home for the Jewish people in Palestine without prejudice to the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.[11] Article 22, para.4 of the Covenant, classified certain populations as "communities formerly belonging to the Turkish Empire" as having "reached a stage of development where their existence as [an] independent nation can be provisionally recognized" (the Class A mandates under the League of Nations), and tasked the mandatory with rendering to those territories "administrative advice and assistance until such time as they are able to stand alone"[12][13] . Britain received the mandate for Palestine and Iraq; France gained control of Syria, including present-day Lebanon. Following the 1918 Clemenceau–Lloyd George Agreement, Britain and France also signed the San Remo Oil Agreement, whereby Britain granted France a 25 percent share of the oil production from Mosul, with the remainder going to Britain[14] and France undertook to deliver oil to the Mediterranean. The draft peace agreement with Turkey signed at the conference became the basis for the 1920 Treaty of Sèvres. Germany was called upon to carry out its military and reparation obligations under the Versailles Treaty, and a resolution was adopted in favor of restoring trade with Russia.[7]

Whilst Syria and Mesopotamia were provisionally recognized as states which would be given Mandatory assistance, Palestine would instead be administered by the Mandatory under an obligation to implement the Balfour Declaration and Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations.

San Remo Resolution – 25 April 1920

It was agreed –

(a) To accept the terms of the Mandates Article as given below with reference to Palestine, on the understanding that there was inserted in the procès-verbal an undertaking by the Mandatory Power that this would not involve the surrender of the rights hitherto enjoyed by the non-Jewish communities in Palestine; this undertaking not to refer to the question of the religious protectorate of France, which had been settled earlier in the previous afternoon by the undertaking given by the French Government that they recognized this protectorate as being at an end.

(b) that the terms of the Mandates Article should be as follows:

The High Contracting Parties agree that Syria and Mesopotamia shall, in accordance with the fourth paragraph of Article 22, Part I (Covenant of the League of Nations), be provisionally recognized as independent States, subject to the rendering of administrative advice and assistance by a mandatory until such time as they are able to stand alone. The boundaries of the said States will be determined, and the selection of the Mandatories made, by the Principal Allied Powers.[15]

The High Contracting Parties agree to entrust, by application of the provisions of Article 22, the administration of Palestine, within such boundaries as may be determined by the Principal Allied Powers, to a Mandatory, to be selected by the said Powers. The Mandatory will be responsible for putting into effect the declaration originally made on the 8th [2nd] November, 1917, by the British Government, and adopted by the other Allied Powers, in favour of the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.[a]

La Puissance mandataire s’engage à nommer dans le plus bref delai une Commission speciale pour etudier toute question et toute reclamation concernant les differentes communautes religieuses et en etablir le reglement. Il sera tenu compte dans la composition de cette Commission des interets religieux en jeu. Le President de la Commission sera nommé par le Conseil de la Societé des Nations. [The Mandatory undertakes to appoint in the shortest time a special commission to study any subject and any queries concerning the different religious communities and regulations. The composition of this Commission will reflect the religious interests at stake. The President of the Commission will be appointed by the Council of the League of Nations.]

The terms of the mandates in respect of the above territories will be formulated by the Principal Allied Powers and submitted to the Council of the League of Nations for approval.

Turkey hereby undertakes, in accordance with the provisions of Article [132 of the Treaty of Sèvres] to accept any decisions which may be taken in this connection.

(c) Les mandataires choisis par les principales Puissances alliés sont: la France pour la Syrie, et la Grande Bretagne pour la Mesopotamie, et la Palestine. [The officers chosen by the principal allied Powers are: France for Syria and Great Britain for Mesopotamia and Palestine.]

In reference to the above decision the Supreme Council took note of the following reservation of the Italian Delegation:

La Delegation Italienne en consideration des grands interêts economiques que l’Italie en tant que puissance exclusivement mediterranéenne possède en Asie Mineure, reserve son approbation à la presente resolution, jusqu’au reglement des interêts italiens en Turquie d’Asie. [The Italian delegation, in view of the great economic interests that Italy, as an exclusively Mediterranean power, possesses in Asia Minor, withholds its approval of this resolution until Italian interests in Turkey in Asia shall have been settled.][16]

Subsequent events

While Transjordan was not mentioned during the discussions,[17] three months later, in July 1920, the French defeat of the Arab Kingdom of Syria state precipitated the British need to know 'what is the "Syria" for which the French received a mandate at San Remo?' and "does it include Transjordania?"[18] – it subsequently decided to pursue a policy of associating Transjordan with the mandated area of Palestine but not to apply the special provisions which were intended to provide a national home for the Jewish people West of the Jordan[b][c][d][e] – and the French proclaimed Greater Lebanon and other component states of its Syrian mandate on 31 August 1920. For France, the San Remo decision meant that most of its claims in Syria were internationally recognized and relations with Faisal were now subject to French military and economic considerations. The ability of Great Britain to limit French action was also significantly diminished.[19] France issued an ultimatum and intervened militarily at the Battle of Maysalun in July 1920, deposing the Arab government and removing King Faisal from Damascus in August 1920. In 1920, Great Britain appointed Herbert Samuel, 1st Viscount Samuel as high commissioner and established a mandatory government in Palestine that remained in power until 1948.[20]

Article 22 of the League of Nations Covenant, which contained the general rules to be applied to all Mandated Territories, was written two months before the signing of the Versaille Peace Treaty. It was not known at that time to which territories paragraphs 4, 5 and 6 would relate. The territories which came under the regime set up by this article were three former parts of the Ottoman Empire and seven former overseas possessions of Germany referred to in Part IV, Section I, of the treaty of peace. Those 10 territorial areas were originally administered under 15 mandates.[21]

See also

Notes

- ^ Quigley (2010, p. 29) "The provision on Palestine thus read differently from the provision on Syria and Mesopotamia and omitted reference to any provisional recognition of Palestine as an independent state. The provision on Palestine read differently for the apparent reason that the mandatory would administer, hence the thrust of the provision was to make that point clear. In any event, the understanding of the resolution was that all the Class A mandates were states. Before leaving San Remo, Curzon telegraphed a memorandum to the Foreign Office in London to explain the San Remo decisions. In explaining to the Foreign Office how the boundaries between the mandate territories would he fixed, Curzon wrote that "[t]he boundaries of these States will not be included in the Peace Treaty [with Turkey] but are also to be determined by the principal Allied Powers."

- ^ Karsh & Karsh (2001) A telegram from Earl Curzon to Sir Herbert Samuel, dated 6 August 1920 stated: "I suggest that you should let it be known forthwith that in the area south of the Sykes-Picot line, we will not admit French authority and that our policy for this area to be independent but in closest relations with Palestine;" (in Rohan Butler et al., Documents of British Foreign Policy, 1919–1939, first series volume XIII London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1963, p. 331.) Karsh writes that at the same time Curzon wrote to Vansittart, stating: "His Majesty's Government are already treating 'Trans-Jordania' as separate from the Damascus State, while at the same time avoiding any definite connection between it and Palestine, thus leaving the way open for the establishment there, should it become advisable, of some form of independent Arab government, perhaps by arrangement with King Hussein or other Arab chiefs concerned."

- ^ Wilson (1988, p. 44) Since the end of the war the territory north of Ma'an had been ruled by Damascus as a province of Faysal's Kingdom of Syria. Although it fell within the British zone according to the Sykes-Picot agreement, Britain was content with the arrangement because it favoured Arab rule in the interior and Faysal was, after all, British protege. However, when France occupied Damascus the picture changed dramatically. Britain did not want to see France extend its control southward to the borders of Palestine and closer to the Suez Canal.... It suddenly became important to know 'what is the "Syria" for which the French received a mandate at San Remo?' and 'does it include Transjordania?'... The British foreign secretary, Lord Curzon, decided that it did not and that Britain henceforth would regard the area as independent, but in 'closest relation' with Palestine.

- ^ Wilson (1988, pp. 46–48) Samuel then organised a meeting of Transjordanian leaders at Salt on 21 August, at which he would announce British plans... On 20 August Samuel and a few political officers left Jerusalem by car, headed for the Jordan river, the frontier of British territory at that time. ‘It is an entirely irregular proceeding,’ he noted, ‘my going outside my own jurisdiction into a country which was Faisal's, and is still being administered by the Damascus Government, now under French influence. But it is equally irregular for a government under French influence to be exercising functions in territory which is agreed to be within the British sphere: and of the two irregularities I prefer mine.’... The meeting, held in the courtyard of the Catholic church, was attended by about 600 people..... Sentence by sentence his speech describing British policy was translated into Arabic: political officers would be stationed in towns to help organise local governments; Transjordan would not come under Palestinian administration; there would be no conscription and no disarmament......On balance, Samuel's statement of policy was unobjectionable. Three things feared by the Arabs of Transjordan – conscription, disarmament, and annexation by Palestine – were abjured.... The presence of a few British agents, unsupported by troops, seemed a small concession in return for the protection Britain's presence would afford against the French, who, it was feared, might press their occupation southward... Samuel returned to Jerusalem well pleased with the success of his mission. He left behind several officers to see to the administration of Transjordan and the maintenance of British influence.

- ^ Wasserstein (2003, pp. 105–106) "Palestine, therefore, was not partitioned in 1921–1922. Transjordan was not excised but, on the contrary, added to the mandatory area. Zionism was barred from seeking to expand there – but the Balfour Declaration had never previously applied to the area east of the Jordan. Why is this important? Because the myth of Palestine's 'first partition' has become part of the concept of 'Greater Israel' and of the ideology of Jabotinsky's Revisionist movement."

References

- ^ George 2005, p. 6.

- ^ "FRUS: Papers relating to the foreign relations of the United States, The Paris Peace Conference, 1919: The Council of Four: minutes of meetings March 20 to May 24, 1919". digicoll.library.wisc.edu.

- ^ Baker 1979, p. 161.

- ^ Paris 2003, p. 69.

- ^ King, William C. (24 April 1922). King's Complete History of the World War ...: 1914–1918. Europe's War with Bolshevism 1919–1920. War of the Turkish Partition 1920–1921. Warfare in Ireland, India, Egypt, Far East 1916–1921. Epochal Events Thruout the Civilized World from Ferdinand's Assassination to Disarmament Conference. History Associates. ISBN 9780598443120 – via Google Books.

- ^ "San Remo Peace Conference Minutes". Office For Israeli Constitutional Law. 25 April 1920. Archived from the original on 28 July 2019. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

- ^ a b Olson, James Stuart (24 April 1991). Historical Dictionary of European Imperialism. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780313262579 – via Google Books.

- ^ Büssow, Johann (11 August 2011). Hamidian Palestine: Politics and Society in the District of Jerusalem 1872–1908. BRILL. p. 5. ISBN 978-90-04-20569-7. Retrieved 17 May 2013.

- ^ The 1915 Filastin Risalesi ("Palestine Document") is a country survey of the VIII Corps of the Ottoman Army, which identified Palestine as a region including the sanjaqs of Akka (the Galilee), the Sanjaq of Nablus, and the Sanjaq of Jerusalem (Kudus Sherif), see Ottoman Conceptions of Palestine-Part 2: Ethnography and Cartography, Salim Tamari

- ^ "Annex III – Ottoman Administrative Districts – Map". UN. 1915.

- ^ The two-fold aims of the Mandate granted to Britain were reflected in the final text of Palestine Mandate granted to Britain by the League of Nations in 1922 [1]. It preamble stated that the purpose of the Mandate was both "giving effect to the provisions of Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations" and "putting into effect the declaration issued by the British govenemnt on November 2, 1917" (i.e. the Balfour Declaration". Article 2 stated that "The Mandatory shall be responsible for placing the country under such political, administrative and economic conditions as will secure the establishment of the Jewish national home" but also "the development of self-governing institutions, and also for safeguarding the civil and religious rights of all the inhabitants of Palestine, irrespective of race and religion".

- ^ Arnulf Becker Lorca (2014). Mestizo International Law. Cambridge University Press. pp. 296–. ISBN 978-0-521-76338-7.

- ^ Malcolm Evans (24 June 2010). International Law. OUP Oxford. pp. 214–. ISBN 978-0-19-956566-5.

- ^ Blakeslee, George Hubbard; Hall, Granville Stanley; Barnes, Harry Elmer (24 April 1921). "The Journal of International Relations". Clark University – via Google Books.

- ^ Quigley 2010, p. 29.

- ^ San Remo Resolution-Palestine Mandate 1920, MidEastWeb

- ^ Biger 2004, p. 173.

- ^ Hubert Young to Ambassador Hardinge (Paris), 27 July 1920, FO 371/5254, cited in Wilson (1988, p. 44)

- ^ "France in Syria: the abolition of the Sharifian government, April–July 1920. Middle Eastern Studies | HighBeam Research". 27 February 2011. Archived from the original on 27 February 2011.

- ^ Wasserstein, Bernard (1 October 1976). "Herbert Samuel and the Palestine problem". The English Historical Review. XCI (CCCLXI): 753–775. doi:10.1093/ehr/XCI.CCCLXI.753 – via academic.oup.com.

- ^ "FRUS: Papers relating to the foreign relations of the United States, The Paris Peace Conference, 1919: I: The treaty of peace between the Allied and Associated Powers and Germany, signed at Versailles, June 28, 1919". digicoll.library.wisc.edu.

Sources

- Baker, Randall (1979). King Husain and the Kingdom of Hejaz. Oleander. ISBN 978-0900891489.

- Biger, Gideon (2004). The Boundaries of Modern Palestine, 1840–1947. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-76652-8.

- George, Alan (2005). Jordan: Living in the Crossfire. Zed Books. ISBN 978-1842774717.

- Karsh, Efraim; Karsh, Inari (2001). Empires of the Sand: The Struggle for Mastery in the Middle East, 1789–1923. Harvard UP. ISBN 978-0674005419.

- Paris, Timothy J (2003). Britain, the Hashemites and Arab Rule, 1920–1925. Routledge. ISBN 978-0714654515.

- Quigley, John (2010). The Statehood of Palestine: International Law in the Middle East Conflict. CUP. ISBN 978-1139491242.

- Wasserstein, Bernard (2003). Israelis and Palestinians : Why do they fight? Can they stop?. Yale UP. ISBN 978-0300101720.

- Wilson, Mary Christina (1988). King Abdullah, Britain and the Making of Jordan. (Cambridge Middle East Library). CUP. ISBN 978-0521324212.

Further reading

- Fromkin, David (1989). A Peace to End All Peace. New York: Henry Holt.

- Stein, Leonard (1961). The Balfour Declaration. London: Valentine Mitchell.

- "Conferees Depart from San Remo", New York Times, 28 April 1920, Wednesday. "CONFEREES DEPART FROM SAN REMO; Millerand Receives Ovation from Italians on His Homeward Journey. RESULTS PLEASE GERMANS; Berlin Liberal Papers Rejoice at Decision to Invite Chancellor to Spa Conference."

External links

- 1920 conferences

- 1920 in Europe

- 1920 in international relations

- 1920 in Italy

- 20th-century diplomatic conferences

- World War I conferences

- Aftermath of World War I

- Borders of Israel

- Borders of the State of Palestine

- Diplomatic conferences in Italy

- History of Zionism

- Liguria

- Sanremo

- Zionism

- Documents of Mandatory Palestine

- April 1920 events