Samurai

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2021) |

Samurai (侍) or bushi (武士, [bɯ.ɕi]) were members of the warrior class who served as retainers to lords (including daimyo) in Japan. They were originally provincial warriors who served the Kuge and imperial court in the late 12th century, and eventually came to play a major political role until their abolition in the late 1870s during the Meiji era.[1][2]

Although they had predecessors in earlier military and administrative officers, the bushi truly emerged during the Kamakura shogunate, ruling from c.1185 to 1333. They became the ruling political class, with significant power but also significant responsibility. During the 13th century, the bushi proved themselves as adept warriors against the invading Mongols. During the Sengoku Period, the term was vague and some samurai owned land, others were retainers or mercenaries.[3] Many served as retainers to lords (including daimyo). There was a great increase in the number of men who styled themselves samurai by virtue of bearing arms.[4] During the Edo period, 1603 to 1868, they were mainly the stewards and chamberlains of the daimyo estates, roles they had also filled in the past. During the Edo period, they came to represent a hereditary class.[5] On the other hand, from the mid-Edo period, chōnin (townsman) and farmers could be promoted to the samurai class by being adopted into gokenin families or by serving in daikan offices, and low-ranking samurai could be transferred to lower social classes, such as chōnin, by changing jobs.[6][7]

In the 1870s, samurai families comprised 5% of the population.[citation needed] As modern militaries emerged in the 19th century, the samurai were rendered increasingly obsolete and very expensive to maintain compared to the average conscript soldier. The Meiji Restoration formally abolished the status, and most former samurai became Shizoku. This allowed them to move into professional and entrepreneurial roles.

Terminology

In Japanese, historical warriors are usually referred to as bushi (武士, [bɯ.ɕi]), meaning 'warrior', or buke (武家), meaning 'military family'. According to translator William Scott Wilson: "In Chinese, the character 侍 was originally a verb meaning 'to wait upon', 'accompany persons' in the upper ranks of society, and this is also true of the original term in Japanese, saburau. In both countries the terms were nominalized to mean 'those who serve in close attendance to the nobility', the Japanese term saburai being the nominal form of the verb." According to Wilson, an early reference to the word saburai appears in the Kokin Wakashū, the first imperial anthology of poems, completed in the early 900s.[8]

Originally, the word samurai referred to anyone who served the emperor, the imperial family, or the imperial court nobility, even in a non-military capacity.[9][10] It was not until the 17th century that the term gradually became a title for military servants of warrior families, so that, according to Michael Wert, "a warrior of elite stature in pre-seventeenth-century Japan would have been insulted to be called a 'samurai'".[11]

In modern usage, bushi is often used as a synonym for samurai.[12][13][14]

The changing definition of "samurai"

The definition of "samurai" varies from period to period. From the Heian period to the Edo period, bushi were people who fought with weapons for a living.[9][10] In the Heian period, on the other hand, the definition of samurai referred to officials who served the emperor, the imperial family, and the nobles of the imperial court, the upper echelons of society. They were responsible for assisting the nobles in their daily duties, guarding the nobles, guarding the court, arresting bandits, and suppressing civil wars, much like secretaries, butlers, and police officers today.[9][10] Samurai in this period referred to the Fifth (go-i) and Sixth Ranks (roku-i) of the court ranks.

During the Kamakura period, the definition of samurai became synonymous with gokenin (御家人), which refers to bushi who owned territory and served the shogun. However, some samurai of exceptional status, hi-gokenin (非御家人), did not serve the shogun. Subordinate bushi in the service of the samurai were called rōtō, rōdō (郎党) or rōjū (郎従). Some of the rōtō were given a territory and a family name, and as samuraihon or saburaibon (侍品), they acquired a status equivalent to that of a samurai. In other words, a high-ranking person among the bushi was called a samurai.[9][10]

During the Muromachi period, as in the Kamakura period, the definition of samurai referred to high-ranking bushi in the service of the shogun. Bushi serving shugo daimyo (守護大名, feudal lords) were not considered samurai. Those who did not serve a particular lord, such as the rōnin (浪人), who were vagabonds, the nobushi (野武士), who were armed peasants, and the ashigaru (足軽), who were temporarily hired foot soldiers, were not considered samurai.[9][10]

During the Sengoku period, the traditional master-servant relationship in Japanese society collapsed, and the traditional definition of samurai changed dramatically. Samurai no longer referred to those serving the shogun or emperor, and anyone who distinguished themselves in war could become samurai regardless of their social status.[10] Jizamurai (地侍) came from the powerful myōshu (名主), who owned farmland and held leadership positions in their villages, and became vassals of sengoku daimyō (戦国大名). Their status was half farmer, half bushi (samurai).[15] On the other hand, it also referred to local bushi who did not serve the shogun or daimyo. According to Stephen Morillo, during this period the term refers to "a retainer of a lord - usually ... the retainer of a daimyo" and that the term samurai "marks social function and not class", and "all sorts of soldiers, including pikemen, bowmen, musketeers and horsemen were samurai".[16]

During the Azuchi–Momoyama period (late Sengoku period), "samurai" often referred to wakatō (若党), the lowest-ranking bushi, as exemplified by the provisions of the temporary law Separation Edict enacted by Toyotomi Hideyoshi in 1591. This law regulated the transfer of status classes:samurai (wakatō), chūgen (中間), komono (小者), and arashiko (荒子). These four classes and the ashigaru were chōnin (町人, townspeople) and peasants employed by the bushi and fell under the category of buke hōkōnin (武家奉公人, servants of the buke).[17][18] In times of war, samurai (wakatō) and ashigaru were fighters, while the rest were porters. Generally, samurai (wakatō) could take family names, while some ashigaru could, and only samurai (wakatō) were considered samurai class.[17][19] Wakatō, like samurai, had different definitions in different periods, meaning a young bushi in the Muromachi period and a rank below kachi (徒士) and above ashigaru in the Edo period.

In the early Edo period, even some daimyō (大名, feudal lords) with territories of 10,000 koku or more called themselves samurai.[6] At the beginning of the Tokugawa shogunate, there was no clear distinction between hatamoto (旗本) and gokenin, which referred to direct vassals of the shogun, but from the second half of the 17th century a distinction was made between hatamoto, direct vassals with territories of 10,000 koku or less who were entitled to an audience with the shogun, and gokenin, those without such rights. Samurai referred to hatamoto in the Tokugawa shogunate and to chūkoshō (中小姓) or higher status bushi in each han (藩, domains). During this period, most bushi came to serve the shogun and the daimyo of each domains, and as the distinction between bushi and chōnin or peasants became stricter, the boundaries between the definitions of samurai and bushi became blurred. Since then, the term "samurai" has been used to refer to "bushi".[9][10] Officially, however, the high-ranking bushi were called samurai and the low-ranking bushi were called kachi (徒士). Samurai and kachi were represented by the word shibun (士分), a status that can be translated as warrior class, bushi class, or samurai class. Samurai were entitled to an audience with their lord, were allowed to ride horses, and received rice from the land and peasants under their control, while kachi were not entitled to an audience with their lord, guarded their lord on foot, and received rice from the stores of the shogunate and each domain. Gokenin, the status of kachi, were financially impoverished and supported themselves by making bamboo handicrafts and umbrellas and selling plants. The shibun status of samurai and kachi was clearly distinguished from the keihai (軽輩) status of the ashigaru and chūgen who served them, but it was more difficult to rise from kachi to samurai than from ashigaru to kachi, and the status gap between samurai, who were high-ranking bushi, and kachi, who were low-ranking bushi, was quite wide. During the Edo Period, samurai represented a hereditary social class defined by the right to bear arms and to hold public office, as well as high social status.[5] From the mid-Edo period, chōnin and farmers could be promoted to the samurai class by being adopted into gokenin families, or by serving in daikan offices, and kachi could be transferred to lower social classes, such as chōnin, by changing jobs.

History

Asuka and Nara periods

As part of the Taihō Code of 702, and the later Yōrō Code,[20] the population was required to report regularly for the census, a precursor for national conscription. With an understanding of how the population was distributed, Emperor Monmu introduced a law whereby 1 in 3–4 adult males were drafted into the state military. These soldiers were required to supply their own weapons, and in return were exempted from duties and taxes.[21]

The Taihō Code classified most Imperial bureaucrats into 12 ranks, each divided into two sub-ranks, 1st rank being the highest adviser to the emperor. Those of 6th rank and below were referred to as "samurai" and dealt with day-to-day affairs and were initially civilian public servants, in keeping with the original derivation of this word from saburau, a verb meaning 'to serve'.[22]

Heian period

In 780, general conscription was abolished, and the government relied solely on units of capable warriors called kondei recruited from the sons of wealthy peasants and provincial officials. Another principle of the Ritsuryō system had already begun to be abandoned. All the land belonged to the state, and had been distributed on a per capita basis to farmers. However, in 743, farmers were allowed to cultivate reclaimed land in perpetuity. This allowed clan leaders, especially those with lots of slaves, to acquire large amounts of land. Members of the Imperial family, the Kuge and Temples and Shrines received grants of tax-free land. In the 9th Century, the farmers began to give their land over to the nobility in order to avoid taxes. They would then administer and work the land for a payment of rice. This also reduced the wealth of the Emperor, as he had no private land and was dependent on tax income. Many of the farmers armed themselves and formed warrior groups called rōdō. These warriors then followed powerful families like the Minamoto and Taira.[23]

Taira no Masakado, who rose to prominence in the early 10th century, was the first of the local warrior class to revolt against the imperial court.[24] He had served Fujiwara no Tadahira as a young man, but eventually won a power struggle within the Taira clan and became a powerful figure in the Kanto region. In 939, Fujiwara no Haruaki, a powerful figure in the Hitachi province, fled to Masakado. He was wanted for tyranny by Fujiwara no Korechika, an Kokushi (国司, imperial court official) who oversaw the province of Hitachi, and Fujiwara no Korechika demanded that Masakado hand over Fujiwara no Haruaki. Masakado refused, and war broke out between Masakado and Fujiwara no Korechika, with Masakado becoming an enemy of the imperial court. Masakado proclaimed that the Kanto region under his rule was independent of the Imperial Court and called himself the Shinnō (新皇, New Emperor). In response, the imperial court sent a large army led by Taira no Sadamori to kill Masakado. As a result, Masakado was killed in battle in February 940. He is still revered as one of the three great onryō (怨霊, vengeful spirits) of Japan.[24][25]

The Heian period saw the appearance of distinctive Japanese armor and weapons. Typical examples are the tachi (long sword) and naginata (halberd) used in close combat, and the ō-yoroi and dō-maru styles of armor. High-ranking samurai equipped with yumi (bows) who fought on horseback wore ō-yoroi, while lower-ranking samurai equipped with naginata who fought on foot wore dō-maru.[26]

Late Heian period and the rise of samurai

During the reigns of Emperor Shirakawa and Emperor Toba, the Taira clan became Kokushi (国司), or overseers of various regions, and accumulated wealth by taking samurai from various regions as their retainers. In the struggle for the succession of Emperor Toba, Emperor Sutoku and Emperor Go-Shirakawa, each with his samurai class on his side, fought the Hōgen rebellion, which was won by Emperor Go-Shirakawa, who had Taira no Kiyomori and Minamoto no Yoshitomo on his side. Later, Taira no Kiyomori defeated Minamoto no Yoshitomo in the Heiji rebellion and became the first samurai-born aristocratic class, eventually becoming Daijō-daijin, the highest position of the aristocratic class, and the Taira clan monopolized important positions at the Imperial Court and wielded power. The victor, Taira no Kiyomori, became an imperial advisor and was the first warrior to attain such a position. He eventually seized control of the central government, establishing the first samurai-dominated government and relegating the emperor to figurehead status. The clan had its women marry emperors and exercise control through the emperor.[27]

-

Heiji rebellion in 1159

-

16th century illustration samurai raiding the house of Minamoto no Yoshitsune

However, when Taira no Kiyomori used his power to have the child of his daughter Taira no Tokuko and Emperor Takakura installed as Emperor Antoku, there was widespread opposition. Prince Mochihito, no longer able to assume the imperial throne, called upon the Minamoto clan to raise an army to defeat the Taira clan, and the Genpei War began. Minamoto no Yoshinaka expelled the Taira clan from Kyoto, and although he was initially welcomed by the hermit Emperor Go-Shirakawa, he became estranged and isolated due to the disorderly military discipline and lack of political power under his command. He staged a coup, overthrew the emperor's entourage, and became the first of the Minamoto clan to assume the office of Sei-i Taishōgun (shogun). In response, Minamoto no Yoritomo sent Minamoto no Noriyori and Minamoto no Yoshitsune to defeat Yoshinaka, who was killed within a year of becoming shogun. In 1185, the Taira clan was finally defeated in the Battle of Dan-no-ura, and the Minamoto clan came to power.[27]

Kamakura shogunate and the Mongol invasions

The victorious Minamoto no Yoritomo established the superiority of the samurai over the aristocracy. In 1185, Yoritomo obtained the right to appoint shugo and jitō, and was allowed to organize soldiers and police, and to collect a certain amount of tax.[28] Initially, their responsibility was restricted to arresting rebels and collecting needed army provisions and they were forbidden from interfering with kokushi officials, but their responsibility gradually expanded. Thus, the samurai class became the political ruling power in Japan.

In 1190 he visited Kyoto and in 1192 became Sei'i Taishōgun, establishing the Kamakura shogunate, or Kamakura bakufu. Instead of ruling from Kyoto, he set up the shogunate in Kamakura, near his base of power. "Bakufu" means "tent government", taken from the encampments the soldiers lived in, in accordance with the Bakufu's status as a military government.[29]

The Kamakura period (1185–1333) saw the rise of the samurai under shogun rule as they were "entrusted with the security of the estates" and were symbols of the ideal warrior and citizen.[30] Originally, the emperor and non-warrior nobility employed these warrior nobles. In time they amassed enough manpower, resources and political backing, in the form of alliances with one another, to establish the first samurai-dominated government. As the power of these regional clans grew, their chief was typically a distant relative of the emperor and a lesser member of either the Fujiwara, Minamoto, or Taira clan.

From the Kamakura period onwards, emphasis was put on training samurai from childhood in using "the bow and sword".[31]

In the late Kamakura period, even the most senior samurai began to wear dō-maru, as the heavy and elegant ō-yoroi were no longer respected. Until then, the body was the only part of the dō-maru that was protected, but for higher-ranking samurai, the dō-maru also came with a kabuto (helmet) and shoulder guards.[26] For lower-ranked samurai, the haraate was introduced, the simplest style of armor that protected only the front of the torso and the sides of the abdomen. In the late Kamakura period, a new type of armor called haramaki appeared, in which the two ends of the haraate were extended to the back to provide greater protection.[32]

-

Samurai of the Shōni clan gather to defend against Kublai Khan's Mongolian army during the first Mongol invasion of Japan in 1274.

-

Battle of Yashima folding screens

Various samurai clans struggled for power during the Kamakura shogunate. Zen Buddhism spread among the samurai in the 13th century and helped shape their standards of conduct, particularly in overcoming the fear of death and killing. Among the general populace Pure Land Buddhism was favored however.

In 1274, the Mongol-founded Yuan dynasty in China sent a force of some 40,000 men and 900 ships to invade Japan in northern Kyūshū. Japan mustered a mere 10,000 samurai to meet this threat. The invading army was harassed by major thunderstorms throughout the invasion, which aided the defenders by inflicting heavy casualties. The Yuan army was eventually recalled, and the invasion was called off. The Mongol invaders used small bombs, which was likely the first appearance of bombs and gunpowder in Japan.

The Japanese defenders recognized the possibility of a renewed invasion and began construction of a great stone barrier around Hakata Bay in 1276. Completed in 1277, this wall stretched for 20 kilometers around the bay. It later served as a strong defensive point against the Mongols. The Mongols attempted to settle matters in a diplomatic way from 1275 to 1279, but every envoy sent to Japan was executed.

Leading up to the second Mongolian invasion, Kublai Khan continued to send emissaries to Japan, with five diplomats sent in September 1275 to Kyūshū. Hōjō Tokimune, the shikken of the Kamakura shogun, responded by having the Mongolian diplomats brought to Kamakura and then beheading them.[33] The graves of the five executed Mongol emissaries exist to this day in Kamakura at Tatsunokuchi.[34] On 29 July 1279, five more emissaries were sent by the Mongol empire, and again beheaded, this time in Hakata. This continued defiance of the Mongol emperor set the stage for one of the most famous engagements in Japanese history.

In 1281, a Yuan army of 140,000 men with 5,000 ships was mustered for another invasion of Japan. Northern Kyūshū was defended by a Japanese army of 40,000 men. The Mongol army was still on its ships preparing for the landing operation when a typhoon hit north Kyūshū island. The casualties and damage inflicted by the typhoon, followed by the Japanese defense of the Hakata Bay barrier, resulted in the Mongols again being defeated.

The thunderstorms of 1274 and the typhoon of 1281 helped the samurai defenders of Japan repel the Mongol invaders despite being vastly outnumbered. These winds became known as kami-no-Kaze, which literally translates as "wind of the gods".[35] This is often given a simplified translation as "divine wind". The kami-no-Kaze lent credence to the Japanese belief that their lands were indeed divine and under supernatural protection.

Nanboku-chō and Muromachi period

In 1336, Ashikaga Takauji, who opposed Emperor Godaigo, established the Ashikaga Shogunate with Emperor Kōgon. As a result, the southern court, descended from Emperor Godaigo, and the northern court, descended from Emperor Kogon, were established side by side. This period of coexistence of the two dynasties is called the Nanboku-chō period, which corresponds to the beginning of the Muromachi period. The Northern Court, supported by the Ashikaga Shogunate, had six emperors, and in 1392 the Imperial Court was reunited by absorbing the Southern Court, although the modern Imperial Household Agency considers the Southern Court to be the legitimate emperor.[36] The de facto rule of Japan by the Ashikaga Shogunate lasted until the Onin War, which broke out in 1467.

From 1346 to 1358 during the Nanboku-cho period, the Ashikaga shogunate gradually expanded the authority of the Shugo (守護), the local military and police officials established by the Kamakura shogunate, giving the Shugo jurisdiction over land disputes between gokenin (御家人) and allowing the Shugo to receive half of all taxes from the areas they controlled. The Shugo shared their newfound wealth with the local samurai, creating a hierarchical relationship between the Shugo and the samurai, and the first early daimyo (大名, feudal lords), called shugo daimyo (守護大名), appeared.[37]

The innovations of Sōshū swordsmiths in the late Kamakura period allowed them to produce Japanese swords with tougher blades than before, and during the Nanboku-chō period, ōdachi (large/great sword) were at their peak as weapons for the samurai.[38]

Until the Mongol invasion in the late Kamakura period, the main battle was fought by small groups of warriors using yumi (bows) from horseback, and close combat was a secondary battle. From the Nanboku-chō period to the Muromachi period, large groups of infantrymen became more active in battle, close combat became more important, and the naginata and tachi, which had been used since the Heian period, were used more. The yari (spear) was not yet a major weapon in this period.[39][40]

During the Nanboku-chō period, many lower-class foot soldiers called ashigaru began to participate in battles, and the popularity of haramaki increased. During the Nanboku-chō and Muromachi periods, dō-maru and haramaki became the norm, and senior samurai also began to wear haramaki by adding kabuto (helmet), men-yoroi (face armor), and gauntlet.[41]

Issues of inheritance caused family strife as primogeniture became common, in contrast to the division of succession designated by law before the 14th century. Invasions of neighboring samurai territories became common to avoid infighting, and bickering among samurai was a constant problem for the Kamakura and Ashikaga shogunates.

Sengoku period

The outbreak of the Onin War, which began in 1467 and lasted about 10 years, devastated Kyoto and brought down the power of the Ashikaga Shogunate. This plunged the country into the warring states period, in which daimyo (feudal lords) from different regions fought each other. This period corresponds to the late Muromachi period. There are about nine theories about the end of the Sengoku Period, the earliest being the year 1568, when Oda Nobunaga marched on Kyoto, and the latest being the suppression of the Shimabara Rebellion in 1638. Thus, the Sengoku Period overlaps with the Muromachi, Azuchi–Momoyama, and Edo periods, depending on the theory. In any case, the Sengoku period was a time of large-scale civil wars throughout Japan.[42][43]

Daimyo who became more powerful as the shogunate's control weakened were called sengoku daimyo (戦国大名), and they often came from shugo daimyo, Shugodai (守護代, deputy Shugo), and kokujin or kunibito (国人, local masters). In other words, sengoku daimyo differed from shugo daimyo in that a sengoku daimyo was able to rule the region on his own, without being appointed by the shogun.[37]

During this period, the traditional master-servant relationship between the lord and his vassals broke down, with the vassals eliminating the lord, internal clan and vassal conflicts over leadership of the lord's family, and frequent rebellion and puppetry by branch families against the lord's family.[44] These events sometimes led to the rise of samurai to the rank of sengoku daimyo. For example, Hōjō Sōun was the first samurai to rise to the rank of sengoku daimyo during this period. Uesugi Kenshin was an example of a Shugodai who became sengoku daimyo by weakening and eliminating the power of the lord.[45][46]

This period was marked by the loosening of samurai culture, with people born into other social strata sometimes making a name for themselves as warriors and thus becoming de facto samurai. One such example is Toyotomi Hideyoshi, a well-known figure who rose from a peasant background to become a samurai, sengoku daimyo, and kampaku (Imperial Regent).[47]

From this time on, infantrymen called ashigaru, who were mobilized from the peasantry, were mobilized in even greater numbers than before, and the importance of the infantry, which had begun in the Nanboku-chō period, increased even more.[39] When matchlocks were introduced from Portugal in 1543, Japanese swordsmiths immediately began to improve and mass-produce them. The Japanese matchlock was named tanegashima after the Tanegashima island, which is believed to be the place where it was first introduced to Japan. By the end of the Sengoku Period, there were hundreds of thousands of arquebuses in Japan and a large army of nearly 100,000 men clashing with each other.[48]

On the battlefield, ashigaru began to fight in close formation, using yari (spear) and tanegashima. As a result, yari, yumi (bow), and tanegashima became the primary weapons on the battlefield. The naginata, which was difficult to maneuver in close formation, and the long, heavy tachi fell into disuse and were replaced by the nagamaki, which could be held short, and the short, light katana, which appeared in the Nanboku-cho period and gradually became more common. The tachi was often cut off from the hilt and shortened to make a katana. The tachi, which had become inconvenient for use on the battlefield, was transformed into a symbol of authority carried by high-ranking samurai.[49][50][51][39] Although the ōdachi had become even more obsolete, some sengoku daimyo dared to organize assault and kinsmen units composed entirely of large men equipped with ōdachi to demonstrate the bravery of their armies.[52]

These changes in the aspect of the battlefield during the Sengoku period led to the emergence of the tosei-gusoku style of armor, which improved the productivity and durability of armor. In the history of Japanese armor, this was the most significant change since the introduction of the ō-yoroi and dō-mal in the Heian period. In this style, the number of parts was reduced, and instead armor with eccentric designs became popular.[53]

By the end of the Sengoku period, allegiances between warrior vassals, also known as military retainers, and lords were solidified.[54] Vassals would serve lords in exchange for material and intangible advantages, in keeping with Confucian ideas imported from China between the seventh and ninth centuries.[54] These independent vassals who held land were subordinate to their superiors, who may be local lords or, in the Edo period, the shogun.[54] A vassal or samurai could expect monetary benefits, including land or money, from lords in exchange for their military services.[54]

Azuchi–Momoyama period

The Azuchi-Momoyama period refers to the period when Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi were in power. The name "Azuchi-Momoyama" comes from the fact that Nobunaga's castle, Azuchi Castle, was located in Azuchi, Shiga, and Fushimi Castle, where Hideyoshi lived after his retirement, was located in Momoyama. There are several theories as to when the Azuchi–Momoyama period began: 1568, when Oda Nobunaga entered Kyoto in support of Ashikaga Yoshiaki; 1573, when Oda Nobunaga expelled Ashikaga Yoshiaki from Kyoto; and 1576, when the construction of Azuchi Castle began. In any case, the beginning of the Azuchii–Momoyama period marked the complete end of the rule of the Ashikaga shogunate, which had been disrupted by the Onin War; in other words, it marked the end of the Muromachi period.

Oda, Toyotomi, and Tokugawa

Oda Nobunaga was the well-known lord of the Nagoya area (once called Owari Province) and an exceptional example of a samurai of the Sengoku period.[55] He came within a few years of, and laid down the path for his successors to follow, the reunification of Japan under a new bakufu (shogunate).

Oda Nobunaga made innovations in the fields of organization and war tactics, made heavy use of arquebuses, developed commerce and industry, and treasured innovation. Consecutive victories enabled him to end the Ashikaga Bakufu and disarm of the military powers of the Buddhist monks, which had inflamed futile struggles among the populace for centuries. Attacking from the "sanctuary" of Buddhist temples, they were constant headaches to any warlord and even the emperor, who tried to control their actions. He died in 1582 when one of his generals, Akechi Mitsuhide, turned upon him with his army.

Toyotomi Hideyoshi and Tokugawa Ieyasu, who founded the Tokugawa shogunate, were loyal followers of Nobunaga. Hideyoshi began as a peasant and became one of Nobunaga's top generals, and Ieyasu had shared his childhood with Nobunaga. Hideyoshi defeated Mitsuhide within a month and was regarded as the rightful successor of Nobunaga by avenging the treachery of Mitsuhide. These two were able to use Nobunaga's previous achievements on which build a unified Japan and there was a saying: "The reunification is a rice cake; Oda made it. Hashiba shaped it. In the end, only Ieyasu tastes it."[56] (Hashiba is the family name that Toyotomi Hideyoshi used while he was a follower of Nobunaga.)

Toyotomi Hideyoshi, who became a grand minister in 1586, created a law that non-samurai were not allowed to carry weapons, which the samurai caste codified as permanent and hereditary, thereby ending the social mobility of Japan, which lasted until the dissolution of the Edo shogunate by the Meiji revolutionaries.

The distinction between samurai and non-samurai was so obscure that during the 16th century, most male adults in any social class (even small farmers) belonged to at least one military organization of their own and served in wars before and during Hideyoshi's rule. It can be said that an "all against all" situation continued for a century. The authorized samurai families after the 17th century were those that chose to follow Nobunaga, Hideyoshi and Ieyasu. Large battles occurred during the change between regimes, and a number of defeated samurai were destroyed, went rōnin or were absorbed into the general populace.

Invasions of Korea

In 1592 and again in 1597, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, aiming to invade China through Korea, mobilized an army of 160,000 peasants and samurai and deployed them to Korea in one of the largest military endeavors in Eastern Asia until the late 19th century.[57][58] Taking advantage of arquebus mastery and extensive wartime experience from the Sengoku period, Japanese samurai armies made major gains in most of Korea. A few of the famous samurai generals of this war were Katō Kiyomasa, Konishi Yukinaga, and Shimazu Yoshihiro. Katō Kiyomasa advanced to Orangkai territory (present-day Manchuria) bordering Korea to the northeast and crossed the border into northern China.

Kiyomasa withdrew back to Korea after retaliatory counterattacks from the Jurchens in the area, whose castles his forces had raided.[59] Shimazu Yoshihiro led some 7,000 samurai into battle, and despite being heavily outnumbered, defeated a host of allied Ming and Korean forces at the Battle of Sacheon in 1598. Yoshihiro was feared as Oni-Shimazu ("Shimazu ogre") and his nickname spread across Korea and into China.

In spite of the superiority of Japanese land forces, the two expeditions ultimately failed after Hideyoshi's death,[60] though the invasions did devastate the Korean peninsula. The causes of the failure included Korean naval superiority (which, led by Admiral Yi Sun-sin, harassed Japanese supply lines continuously throughout the wars, resulting in supply shortages on land), the commitment of sizable Ming forces to Korea, Korean guerrilla actions, wavering Japanese commitment to the campaigns as the wars dragged on, and the underestimation of resistance by Japanese commanders.

In the first campaign of 1592, Korean defenses on land were caught unprepared, under-trained, and under-armed. They were rapidly overrun, with only a limited number of successfully resistant engagements against the more experienced and battle-hardened Japanese forces. During the second campaign in 1597, Korean and Ming forces proved far more resilient and with the support of continued Korean naval superiority, managed to limit Japanese gains to parts of southeastern Korea. The final death blow to the Japanese campaigns in Korea came with Hideyoshi's death in late 1598 and the recall of all Japanese forces in Korea by the Council of Five Elders, established by Hideyoshi to oversee the transition from his regency to that of his son Hideyori.

Battle of Sekigahara

Before his death, Hideyoshi ordered that Japan be ruled by a council of the five most powerful sengoku daimyo, Go-Tairō (五大老, Council of Five Elders), and Hideyoshi's five retainers, Go-Bugyō (五奉行, Five Commissioners), until his only heir, the five-year-old Toyotomi Hideyori, reached the age of 16.[61] However, having only the young Hideyori as Hideyoshi's successor weakened the Toyotomi regime. Today, the loss of all of Hideyoshi's adult heirs is considered the main reason for the downfall of the Toyotomi clan.[62][63][64] Hideyoshi's younger brother, Toyotomi Hidenaga, who had supported Hideyoshi's rise to power as a leader and strategist, had already died of illness in 1591, and his nephew, Toyotomi Hidetsugu, who was Hideyoshi's only adult successor, was forced to commit seppuku in 1595 along with many other vassals on Hideyoshi's orders for suspected rebellion.[62][63][64]

In this politically unstable situation, Maeda Toshiie, one of the Gotairō, died of illness, and Tokugawa Ieyasu, one of the Gotairō' who had been second in power to Hideyoshi but had not participated in the war, rose to power, and Ieyasu came into conflict with Ishida Mitsunari, one of the Go-Bukyō and others. This conflict eventually led to the Battle of Sekigahara, in which the Tō-gun (東軍, Eastern Army) led by Ieyasu defeated the Sei-gun (西軍, Western Army) led by Mitsunari, and Ieyasu nearly gained control of Japan.[61]

Social mobility was high, as the ancient regime collapsed and emerging samurai needed to maintain a large military and administrative organizations in their areas of influence. Most of the samurai families that survived to the 19th century originated in this era, declaring themselves to be the blood of one of the four ancient noble clans: Minamoto, Taira, Fujiwara, and Tachibana. In most cases, however, it is difficult to prove these claims.

Tokugawa shogunate

After the Battle of Sekigahara, when the Tokugawa shogunate defeated the Toyotomi clan in the summer campaign of the siege of Osaka in 1615, the long war ended. During the Tokugawa shogunate, samurai increasingly became courtiers, bureaucrats, and administrators rather than warriors. With no warfare since the early 17th century, samurai gradually lost their military function during the Tokugawa era (also called the Edo period).

Following the passing of a law in 1629, samurai on official duty were required to wear two swords).[65] However, by the end of the Tokugawa era, samurai were aristocratic bureaucrats for their daishō, becoming more of a symbolic emblem of power than a weapon used in daily life. They still had the legal right to cut down any commoner who did not show proper respect kiri-sute gomen (斬り捨て御免), but to what extent this right was used is unknown.[66] When the central government forced daimyōs to cut the size of their armies, unemployed rōnin became a social problem.

Theoretical obligations between a samurai and his lord (usually a daimyō) increased from the Genpei era to the Edo era, strongly emphasized by the teachings of Confucius and Mencius, required reading for the educated samurai class. The leading figures who introduced Confucianism in Japan in the early Tokugawa period were Fujiwara Seika (1561–1619), Hayashi Razan (1583–1657), and Matsunaga Sekigo (1592–1657).

Pederasty permeated the culture of samurai in the early seventeenth century.[67] The relentless condemnation of pederasty by Jesuit missionaries also hindered attempts to convert Japan's governing elite to Christianity.[68] Pederasty had become deeply institutionalized among the daimyo and samurai, prompting comparisons to ancient Athens and Sparta.[69] The Jesuits' strong condemnation of the practice alienated many of Japan's ruling class, creating further barriers to their acceptance of Christianity.[70] Tokugawa Iemitsu, the third shogun, was known for his interest in pederasty.[71]

The samurai served as role modeld for the other social classes.[72] With time on their hands, samurai spent more time in pursuit of other interests such as scholarship. After the Edo period, it{{what]} came to cover all of society, and although the shogunate sometimes invited monks as advisors, the nobility was excluded from the government. As a result, samurai began to assume all civilian roles, and from the Edo period onward, samurai shifted their activities from military to political administration. In addition, those who were newly promoted to the shogunate or domain in recognition of talents unrelated to martial arts, such as literature and scholarship, were also given the status of samurai. It can be said that the difference between a samurai and a military officer appears in such a place.[clarification needed] In the Edo period, samurai equivalent to civil servants and administrative officers were called "officials". Samurai were given an honorific title and were called "Obuke-sama".[citation needed]

From the mid-Edo period, wealthy chōnin (townsman) and farmers could join the samurai class by giving a large sum of money to an impoverished gokenin to be adopted into a samurai family and inherit the samurai's position and stipend. The amount of money given to a gokenin varied according to his position: 1,000 ryo for a yoriki and 500 ryo for an kachi (徒士) Some of their descendants were promoted to hatamoto (旗本) and held important positions in the shogunate. Some of the peasants' children were promoted to the samurai class by serving in the daikan (代官) office.[6] Kachi could change jobs and move into the lower classes, such as chōnin. For example, Takizawa Bakin became a chōnin by working for Tsutaya Jūzaburō.[7]

Samurai in Southeast Asia

In the late 1500s, trade between Japan and Southeast Asia accelerated and increased exponentially when the Tokugawa shogunate was established in the early 1600s. The destinations of the trading ships, the red seal ships, were Thailand, the Philippines, Vietnam, Cambodia, etc. Many Japanese moved to Southeast Asia and established Japanese towns there. Many samurai, or rōnin, who had lost their masters after the Battle of Sekigahara, lived in the Japanese towns. The Spaniards in the Philippines, the Dutch of the Dutch East India Company, and the Thais of the Ayutthaya Kingdom saw the value of these samurai as mercenaries and recruited them. The most famous of these mercenaries was Yamada Nagamasa. He was originally a palanquin bearer who belonged to the lowest end of the samurai class, but he rose to prominence in the Ayutthaya Kingdom, now in southern Thailand, and became governor of the Nakhon Si Thammarat Kingdom. When the policy of national isolation (sakoku) was established in 1639, trade between Japan and Southeast Asia ceased, and records of Japanese activities in Southeast Asia were lost for many years after 1688.[73][74][75]

Samurai as diplomatic ambassadors

In 1582, three Kirishitan daimyō, Ōtomo Sōrin, Ōmura Sumitada, and Arima Harunobu, sent a group of boys, their own blood relatives and retainers, to Europe as Japan's first diplomatic mission to Europe. They had audiences with King Philip II of Spain, Pope Gregory XIII, and Pope Sixtus V. The mission returned to Japan in 1590, but its members were forced to renounce, be exiled, or be executed, due to the Tokugawa shogunate's suppression of Christianity.

In 1612, Hasekura Tsunenaga, a vassal of the daimyo Date Masamune, led a diplomatic mission and had an audience with King Philip III of Spain, presenting him with a letter requesting trade, and he also had an audience with Pope Paul V in Rome. He returned to Japan in 1620, but news of the Tokugawa shogunate's suppression of Christianity had already reached Europe, and trade did not take place due to the Tokugawa shogunate's policy of sakoku. In the town of Coria del Rio in Spain, where the diplomatic mission stopped, there were 600 people with the surnames Japon or Xapon as of 2021, and they have passed on the folk tale that they are the descendants of the samurai who remained in the town.[76]

At the end of the Edo period (Bakumatsu era), when Matthew C. Perry came to Japan in 1853 and the sakoku policy was abolished, six diplomatic missions were sent to the United States and European countries for diplomatic negotiations. The most famous were the US mission in 1860 and the European missions in 1862 and 1864. Fukuzawa Yukichi, who participated in these missions, is most famous as a leading figure in the modernization of Japan, and his portrait was selected for the 10,000 yen note.[77]

Modernization

The relative peace of the Tokugawa era was shattered with the arrival of Commodore Matthew Perry's massive U.S. Navy steamships in 1853. Perry used his superior firepower to force Japan to open its borders to trade. Prior to that only a few harbor towns, under strict control from the shogunate, were allowed to participate in Western trade, and even then, it was based largely on the idea of playing the Franciscans and Dominicans against one another (in exchange for the crucial arquebus technology, which in turn was a major contributor to the downfall of the classical samurai).[citation needed]

From 1854, the samurai army and the navy were modernized. A naval training school was established in Nagasaki in 1855. Naval students were sent to study in Western naval schools for several years, starting a tradition of foreign-educated future leaders, such as Admiral Enomoto. French naval engineers were hired to build naval arsenals, such as Yokosuka and Nagasaki. By the end of the Tokugawa shogunate in 1867, the Japanese navy of the shōgun already possessed eight western-style steam warships around the flagship Kaiyō Maru, which were used against pro-imperial forces during the Boshin War, under the command of Admiral Enomoto Takeaki. A French Military Mission to Japan (1867) was established to help modernize the armies of the Bakufu.

The last showing of the original samurai was in 1867 when samurai from Chōshū and Satsuma provinces defeated the shogunate forces in favor of the rule of the emperor in the Boshin War. The two provinces were the lands of the daimyōs that submitted to Ieyasu after the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600.

Dissolution

In the 1870s, samurai comprised five percent of the population, or 400,000 families with about 1.9 million members. They came under direct national jurisdiction in 1869, and of all the classes during the Meiji revolution they were the most affected.[78] Although many lesser samurai had been active in the Meiji restoration, the older ones represented an obsolete feudal institution that had a practical monopoly of military force, and to a large extent of education as well. A priority of the Meiji government was to gradually abolish the entire class of samurai and integrate them into the Japanese professional, military and business classes.[79]

Their traditional guaranteed salaries were very expensive, and in 1873 the government started taxing the stipends and began to transform them into interest-bearing government bonds; the process was completed in 1879. The main goal was to provide enough financial liquidity to enable former samurai to invest in land and industry. A military force capable of contesting not just China but the imperial powers required a large conscript army that closely followed Western standards. The notion of very strict obedience to chain of command was incompatible with the individual authority of the samurai. Samurai now became Shizoku (士族; this status was abolished in 1947). The right to wear a katana in public was abolished, along with the right to execute commoners who paid them disrespect. In 1877, there was a localized samurai rebellion that was quickly crushed.[80]

Younger samurai often became exchange students because they were ambitious, literate and well-educated. On return, some started private schools for higher education, while many samurai became reporters and writers and set up newspaper companies.[81] Others entered governmental service.[82] In the 1880s, 23 percent of prominent Japanese businessmen were from the samurai class; by the 1920s the number had grown to 35 percent.[83]

Philosophy

Honor

In a 16th-century account of Japan sent to Father Ignatius Loyola at Rome, drawn from the statements of Anger (Han-Siro's western name), Xavier describes the importance of honor to the Japanese (Letter preserved at College of Coimbra):

In the first place, the nation with which we have had to do here surpasses in goodness any of the nations lately discovered. I really think that among barbarous nations there can be none that has more natural goodness than the Japanese. They are of a kindly disposition, not at all given to cheating, wonderfully desirous of honour and rank. Honour with them is placed above everything else. There are a great many poor among them, but poverty is not a disgrace to any one. There is one thing among them of which I hardly know whether it is practised anywhere among Christians. The nobles, however poor they may be, receive the same honour from the rest as if they were rich.[84]

Historian H. Paul Varley notes the description of Japan given by Jesuit leader St. Francis Xavier: "There is no nation in the world which fears death less." Xavier further describes the honour and manners of the people: "I fancy that there are no people in the world more punctilious about their honour than the Japanese, for they will not put up with a single insult or even a word spoken in anger." Xavier spent 1549 to 1551 converting Japanese to Christianity. He also observed: "The Japanese are much braver and more warlike than the people of China, Korea, Ternate and all of the other nations around the Philippines."[85]

However, insubordination or gekokujo, a term used in the fifteenth century during widespread rebellion, involved provincial lords defying the shogun, who in turn disregarded the emperor's commands.[86]

Doctrine

In the 13th century, Hōjō Shigetoki wrote: "When one is serving officially or in the master's court, he should not think of a hundred or a thousand people, but should consider only the importance of the master."[87] Carl Steenstrup notes that 13th- and 14th-century warrior writings (gunki) "portrayed the bushi in their natural element, war, eulogizing such virtues as reckless bravery, fierce family pride, and selfless, at times senseless devotion of master and man".[88]

Feudal lords such as Shiba Yoshimasa (1350–1410) stated that a warrior looked forward to a glorious death in the service of a military leader or the emperor:

It is a matter of regret to let the moment when one should die pass by ... First, a man whose profession is the use of arms should think and then act upon not only his own fame, but also that of his descendants. He should not scandalize his name forever by holding his one and only life too dear ... One's main purpose in throwing away his life is to do so either for the sake of the Emperor or in some great undertaking of a military general. It is that exactly that will be the great fame of one's descendants.[89]

In 1412, Imagawa Sadayo wrote a letter of admonishment to his brother stressing the importance of duty to one's master. Imagawa was admired for his balance of military and administrative skills during his lifetime, and his writings became widespread. The letters became central to Tokugawa-era laws and became required study material for traditional Japanese until World War II:[90]

First of all, a samurai who dislikes battle and has not put his heart in the right place even though he has been born in the house of the warrior, should not be reckoned among one's retainers ... It is forbidden to forget the great debt of kindness one owes to his master and ancestors and thereby make light of the virtues of loyalty and filial piety ... It is forbidden that one should ... attach little importance to his duties to his master ... There is a primary need to distinguish loyalty from disloyalty and to establish rewards and punishments.[91]

Similarly, the feudal lord Takeda Nobushige (1525–1561) stated:

In matters both great and small, one should not turn his back on his master's commands ... One should not ask for gifts or enfiefments from the master ... No matter how unreasonably the master may treat a man, he should not feel disgruntled ... An underling does not pass judgments on a superior.[92]

Nobushige's brother Takeda Shingen (1521–1573) also made similar observations:

One who was born in the house of a warrior, regardless of his rank or class, first acquaints himself with a man of military feats and achievements in loyalty ... Everyone knows that if a man doesn't hold filial piety toward his own parents he would also neglect his duties toward his lord. Such a neglect means a disloyalty toward humanity. Therefore such a man doesn't deserve to be called 'samurai'.[93]

The feudal lord Asakura Yoshikage (1428–1481) wrote: "In the fief of the Asakura, one should not determine hereditary chief retainers. A man should be assigned according to his ability and loyalty." Asakura also observed that the successes of his father were obtained by the kind treatment of the warriors and common people living in domain. By his civility, "all were willing to sacrifice their lives for him and become his allies".[94]

Katō Kiyomasa was one of the most powerful and well-known lords of the Sengoku period. He commanded most of Japan's major clans during the invasion of Korea. In a handbook he addressed to "all samurai, regardless of rank", he told his followers that a warrior's only duty in life was to "grasp the long and the short swords and to die". He also ordered his followers to put forth great effort in studying the military classics, especially those related to loyalty and filial piety. He is best known for his quote:[95] "If a man does not investigate into the matter of Bushido daily, it will be difficult for him to die a brave and manly death. Thus it is essential to engrave this business of the warrior into one's mind well."

Nabeshima Naoshige (1538–1618 AD) was another Sengoku daimyō who fought alongside Kato Kiyomasa in Korea. He stated that it was shameful for any man to have not risked his life at least once in the line of duty, regardless of his rank. Nabeshima's sayings were passed down to his son and grandson and became the basis for Tsunetomo Yamamoto's Hagakure. He is best known for his saying, "The way of the samurai is in desperateness. Ten men or more cannot kill such a man."[96][97]

Torii Mototada (1539–1600) was a feudal lord in the service of Tokugawa Ieyasu. On the eve of the battle of Sekigahara, he volunteered to remain behind in the doomed Fushimi Castle while his lord advanced to the east. Torii and Tokugawa both agreed that the castle was indefensible. In an act of loyalty to his lord, Torii chose to remain behind, pledging that he and his men would fight to the finish. As was custom, Torii vowed that he would not be taken alive. In a dramatic last stand, the garrison of 2,000 men held out against overwhelming odds for ten days against the massive army of Ishida Mitsunari's 40,000 warriors. In a moving last statement to his son Tadamasa, he wrote:[98][99]

It is not the Way of the Warrior [i.e., bushidō] to be shamed and avoid death even under circumstances that are not particularly important. It goes without saying that to sacrifice one's life for the sake of his master is an unchanging principle. That I should be able to go ahead of all the other warriors of this country and lay down my life for the sake of my master's benevolence is an honor to my family and has been my most fervent desire for many years.

It is said that both men cried when they parted ways, because they knew they would never see each other again. Torii's father and grandfather had served the Tokugawa before him, and his own brother had already been killed in battle. Torii's actions changed the course of Japanese history. Ieyasu Tokugawa successfully raised an army and won at Sekigahara.

The translator of Hagakure, William Scott Wilson, observed examples of warrior emphasis on death in clans other than Yamamoto's: "he (Takeda Shingen) was a strict disciplinarian as a warrior, and there is an exemplary story in the Hagakure relating his execution of two brawlers, not because they had fought, but because they had not fought to the death".[100][101]

The rival of Takeda Shingen (1521–1573) was Uesugi Kenshin (1530–1578), a legendary Sengoku warlord well versed in the Chinese military classics and who advocated the "way of the warrior as death". Japanese historian Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki describes Uesugi's beliefs as:

Those who are reluctant to give up their lives and embrace death are not true warriors ... Go to the battlefield firmly confident of victory, and you will come home with no wounds whatever. Engage in combat fully determined to die and you will be alive; wish to survive in the battle and you will surely meet death. When you leave the house determined not to see it again you will come home safely; when you have any thought of returning you will not return. You may not be in the wrong to think that the world is always subject to change, but the warrior must not entertain this way of thinking, for his fate is always determined.[102]

Families such as the Imagawa were influential in the development of warrior ethics and were widely quoted by other lords during their lifetime. The writings of Imagawa Sadayo were highly respected and sought out by Tokugawa Ieyasu as the source of Japanese feudal law.

Religious influences

The philosophies of Confucianism,[54] Buddhism and Zen, and to a lesser extent Shinto, influenced the samurai culture. Zen meditation became an important teaching because it offered a process to calm one's mind. The Buddhist concept of reincarnation and rebirth led samurai to abandon torture and needless killing, while some samurai even gave up violence altogether and became Buddhist monks after coming to believe that their killings were fruitless. Some were killed as they came to terms with these conclusions in the battlefield. The most defining role that Confucianism played in samurai philosophy was to stress the importance of the lord-retainer relationship—the loyalty that a samurai was required to show his lord.[citation needed]

Literature on the subject of bushido such as Hagakure ("Hidden in Leaves") by Yamamoto Tsunetomo and Gorin no Sho ("Book of the Five Rings") by Miyamoto Musashi, both written in the Edo period, contributed to the development of bushidō and Zen philosophy.

According to Robert Sharf, "The notion that Zen is somehow related to Japanese culture in general, and bushidō in particular, is familiar to Western students of Zen through the writings of D. T. Suzuki, no doubt the single most important figure in the spread of Zen in the West."[103]

Arts

In December 1547, Francis was in Malacca (Malaysia) waiting to return to Goa (India) when he met a low-ranked samurai named Anjiro (possibly spelled "Yajiro"). Anjiro was not an intellectual, but he impressed Xavier because he took careful notes of everything he said in church. Xavier made the decision to go to Japan in part because this low-ranking samurai convinced him in Portuguese that the Japanese people were highly educated and eager to learn. They were hard workers and respectful of authority. In their laws and customs they were led by reason, and, should the Christian faith convince them of its truth, they would accept it en masse.[104]

By the 12th century, upper-class samurai were highly literate because of the general introduction of Confucianism from China during the 7th to 9th centuries and in response to their perceived need to deal with the imperial court, who had a monopoly on culture and literacy for most of the Heian period. As a result, they aspired to the more cultured abilities of the nobility.[105]

Examples such as Taira Tadanori (a samurai who appears in the Heike Monogatari) demonstrate that warriors idealized the arts and aspired to become skilled in them. Tadanori was famous for his skill with the pen and the sword or the "bun and the bu", the harmony of fighting and learning.

Samurai were expected to be cultured and literate and admired the ancient saying "bunbu-ryōdō" (文武両道, literary arts, military arts, both ways) or "The pen and the sword in accord". By the time of the Edo period, Japan had a higher literacy comparable to that in central Europe.[106]

The number of men who actually achieved the ideal and lived their lives by it was high. An early term for warrior, "uruwashii", was written with a kanji that combined the characters for literary study ("bun" 文) and military arts ("bu" 武), and is mentioned in the Heike Monogatari (late 12th century). The Heike Monogatari makes reference to the educated poet-swordsman ideal in its mention of Taira no Tadanori's death:[107]

Friends and foes alike wet their sleeves with tears and said,

What a pity! Tadanori was a great general,

pre-eminent in the arts of both sword and poetry.

In his book "Ideals of the Samurai" translator William Scott Wilson states:

The warriors in the Heike Monogatari served as models for the educated warriors of later generations, and the ideals depicted by them were not assumed to be beyond reach. Rather, these ideals were vigorously pursued in the upper echelons of warrior society and recommended as the proper form of the Japanese man of arms. With the Heike Monogatari, the image of the Japanese warrior in literature came to its full maturity.[107]

Wilson then translates the writings of several warriors who mention the Heike Monogatari as an example for their men to follow.

A number of warrior writings document this ideal from the 13th century onward. Most warriors aspired to or followed this ideal to varying degrees.[108]

Culture

As aristocrats for centuries, samurai developed their own cultures that influenced Japanese culture as a whole. Waka (Japanese poetry), noh (Japanese dance-drama), kemari (Japanese football game), tea ceremony, and ikebana (Japanese flower arranging) were some of the cultural pursuits enjoyed by the samurai.[109]

Waka poems were also used as jisei no ku (辞世の句, death poems). Hosokawa Gracia, Asano Naganori, and Takasugi Shinsaku are famous for their jisei no ku.

Noh and kemari were promoted by the Ashikaga shogunate and became popular among daimyo (feudal lords) and samurai.[110][111] During the Sengoku period, the appreciation of noh and the practice of tea ceremonies were valued for socializing and exchanging information, and were essential cultural pursuits for daimyo and samurai. The view of life and death expressed in noh plays was something the samurai of the time could relate to. Owning tea utensils used in the tea ceremony was a matter of prestige for daimyo and samurai, and in some cases tea utensils were given in exchange for land as a reward for military service. The chashitsu (small tea room) was also used as a place for political meetings, as it was suitable for secret talks, and the tea ceremony sometimes brought together samurai and townspeople who did not normally interact.[111]

Education

In general, samurai, aristocrats, and priests had a very high literacy rate in kanji. Recent studies have shown that literacy in kanji among other groups in society was somewhat higher than previously understood. For example, court documents, birth and death records and marriage records from the Kamakura period, submitted by farmers, were prepared in Kanji. Both the kanji literacy rate and skills in math improved toward the end of Kamakura period.[105]

Some samurai had buke bunko, or "warrior library", a personal library that held texts on strategy, the science of warfare, and other documents that would have proved useful during the warring era of feudal Japan. One such library held 20,000 volumes. The upper class had Kuge bunko, or "family libraries", that held classics, Buddhist sacred texts, and family histories, as well as genealogical records.[112]

There were to Lord Eirin's character many high points difficult to measure, but according to the elders the foremost of these was the way he governed the province by his civility. It goes without saying that he acted this way toward those in the samurai class, but he was also polite in writing letters to the farmers and townspeople, and even in addressing these letters he was gracious beyond normal practice. In this way, all were willing to sacrifice their lives for him and become his allies.[113]

In a letter dated 29 January 1552, St Francis Xavier observed the ease of which the Japanese understood prayers due to the high level of literacy in Japan at that time:

In a letter to Father Ignatius Loyola at Rome, Xavier further noted the education of the upper classes:

The Nobles send their sons to monasteries to be educated as soon as they are 8 years old, and they remain there until they are 19 or 20, learning reading, writing and religion; as soon as they come out, they marry and apply themselves to politics.

Names

A samurai was usually named by combining one kanji from his father or grandfather and one new kanji. Samurai normally used only a small part of their total name.

For example, the full name of Oda Nobunaga was "Oda Kazusanosuke Saburo Nobunaga" (織田上総介三郎信長), in which "Oda" is a clan or family name, "Kazusanosuke" is a title of vice-governor of Kazusa province, "Saburo" is a formal nickname (''yobina''), and "Nobunaga" is an adult name (''nanori'') given at genpuku, the coming of age ceremony. A man was addressed by his family name and his title, or by his yobina if he did not have a title. However, the nanori was a private name that could be used by only a very few, including the emperor. Samurai could choose their own nanori and frequently changed their names to reflect their allegiances.

Samurai were given the privilege of carrying two swords and using 'samurai surnames' to identify themselves from the common people.[114]

Marriage

Samurai had arranged marriages, which were arranged by a go-between of the same or higher rank. While for those samurai in the upper ranks this was a necessity (as most had few opportunities to meet women), this was a formality for lower-ranked samurai. Most samurai married women from a samurai family, but for lower-ranked samurai, marriages with commoners were permitted. In these marriages a dowry was brought by the woman and was used to set up the couple's new household.

A samurai could take concubines, but their backgrounds were checked by higher-ranked samurai. In many cases, taking a concubine was akin to a marriage. Kidnapping a concubine, although common in fiction, would have been shameful, if not criminal. If the concubine was a commoner, a messenger was sent with betrothal money or a note for exemption of tax to ask for her parents' acceptance. Even though the woman would not be a legal wife, a situation normally considered a demotion, many wealthy merchants believed that being the concubine of a samurai was superior to being the legal wife of a commoner. When a merchant's daughter married a samurai, her family's money erased the samurai's debts, and the samurai's social status improved the standing of the merchant family. If a samurai's commoner concubine gave birth to a son, the son could inherit his father's social status.

A samurai could divorce his wife for a variety of reasons with approval from a superior, but divorce was, while not entirely nonexistent, a rare event. A wife's failure to produce a son was cause for divorce, but adoption of a male heir was considered an acceptable alternative to divorce. A samurai could divorce for personal reasons, even if he simply did not like his wife, but this was generally avoided as it would embarrass the person who had arranged the marriage. A woman could also arrange a divorce, although it would generally take the form of the samurai divorcing her. After a divorce, samurai had to return the betrothal money, which often prevented divorces.

Women

Maintaining the household was the main duty of women of the samurai class. This was especially crucial during early feudal Japan, when warrior husbands were often traveling abroad or engaged in clan battles. The wife, or okugatasama (meaning: one who remains in the home), was left to manage all household affairs, care for the children, and perhaps even defend the home forcibly. For this reason, many women of the samurai class were trained in wielding a polearm called a naginata or a special knife called the kaiken in an art called tantojutsu (lit. the skill of the knife), which they could use to protect their household, family, and honor if the need arose. There were women who actively engaged in battles alongside male samurai in Japan, although most of these female warriors were not formal samurai.[115]

A samurai's daughter's greatest duty was political marriage. These women married members of enemy clans of their families to form a diplomatic relationship. These alliances were stages for many intrigues, wars and tragedies throughout Japanese history. A woman could divorce her husband if he did not treat her well and also if he was a traitor to his wife's family. A famous case was that of Oda Tokuhime (daughter of Oda Nobunaga); irritated by the antics of her mother-in-law, Lady Tsukiyama (the wife of Tokugawa Ieyasu), she was able to get Lady Tsukiyama arrested on suspicion of communicating with the Takeda clan (then a great enemy of Nobunaga and the Oda clan). Ieyasu also arrested his own son, Matsudaira Nobuyasu, who was Tokuhime's husband, because Nobuyasu was close to his mother Lady Tsukiyama. To assuage his ally Nobunaga, Ieyasu had Lady Tsukiyama executed in 1579 and that same year ordered his son to commit seppuku to prevent him from seeking revenge for the death of his mother.[citation needed]

Though women of wealthier samurai families enjoyed perks of their elevated position in society, such as avoiding the physical labor that those of lower classes often engaged in, they were still viewed as far beneath men. Women were prohibited from engaging in any political affairs and were usually not the heads of their household. This does not mean that women in the samurai class were always powerless. Samurai women wielded power at various occasions. Throughout history, several women of the samurai class have acquired political power and influence, even though they have not received these privileges de jure.

After Ashikaga Yoshimasa, 8th shōgun of the Muromachi shogunate, lost interest in politics, his wife Hino Tomiko largely ruled in his place. Nene, wife of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, was known to overrule her husband's decisions at times, and Yodo-dono, his concubine, became the de facto master of Osaka castle and the Toyotomi clan after Hideyoshi's death. Tachibana Ginchiyo was chosen to lead the Tachibana clan after her father's death. Yamauchi Chiyo, wife of Yamauchi Kazutoyo, has long been considered the ideal samurai wife. According to legend, she made her kimono out of a quilted patchwork of bits of old cloth and saved pennies to buy her husband a magnificent horse, on which he rode to many victories. The fact that Chiyo (though she is better known as "Wife of Yamauchi Kazutoyo") is held in such high esteem for her economic sense is illuminating in the light of the fact that she never produced an heir and the Yamauchi clan was succeeded by Kazutoyo's younger brother. The source of power for women may have been that samurai left their finances to their wives. Several women ascended the Chrysanthemum Throne as a female imperial ruler (女性天皇, josei tennō)

As the Tokugawa period progressed more value became placed on education, and the education of females beginning at a young age became important to families and society as a whole. Marriage criteria began to weigh intelligence and education as desirable attributes in a wife, right along with physical attractiveness. Though many of the texts written for women during the Tokugawa period only pertained to how a woman could become a successful wife and household manager, there were those that undertook the challenge of learning to read, and also tackled philosophical and literary classics. Nearly all women of the samurai class were literate by the end of the Tokugawa period.

-

Japanese woman preparing for ritual suicide

-

Yuki no Kata defending Tsu Castle. 18th century

-

A samurai class woman

Combat techniques

During the existence of the samurai, two opposite types of organization reigned. The first type were recruits-based armies: at the beginning, during the Nara period, samurai armies relied on armies of Chinese-type recruits and towards the end in infantry units composed of ashigaru. The second type of organization was that of a samurai on horseback who fought individually or in small groups.[116]

At the beginning of the contest, a series of bulbous-headed arrows were shot, which buzzed in the air. The purpose of these shots was to call the kami to witness the displays of courage that were about to unfold. After a brief exchange of arrows between the two sides, a contest called ikkiuchi (一 騎 討 ち) was developed, where great rivals on both sides faced each other.[116] After these individual combats, the major combats were given way, usually sending infantry troops led by samurai on horseback. At the beginning of the samurai battles, it was an honor to be the first to enter battle. This changed in the Sengoku period with the introduction of the arquebus.[117]

At the beginning of the use of firearms, the combat methodology was as follows: at the beginning an exchange of arquebus shots was made at a distance of approximately 100 meters; when the time was right, the ashigaru spearmen were ordered to advance and finally the samurai would attack, either on foot or on horseback.[117] The army chief would sit in a scissor chair inside a semi-open tent called maku, which exhibited its respective mon and represented the bakufu, "government from the maku."[118]

In the middle of the contest, some samurai decided to get off the horse and seek to cut off the head of a worthy rival. This act was considered an honor. Through it they gained respect among the military class.[119] After the battle, the high-ranking samurai normally celebrated with a tea ceremony, and the victorious general reviewed the heads of the most important members of the enemy which had been cut.[120]

Most of the battles were not resolved in the ideal manner mentioned above. Most wars were won through surprise attacks, such as night raids, fires, etc. The renowned samurai Minamoto no Tametomo said:

According to my experience, there is nothing more advantageous when it comes to crushing the enemy than a night attack [...]. If we set fire to three of the sides and close the passage through the room, those who flee from the flames will be shot down by arrows, and those who seek to escape from them will not be able to flee from the flames.

Head collection

Cutting off the head of a worthy rival on the battlefield was a source of great pride and recognition. There was a detailed ritual to beautify the severed heads: first they were washed and combed,[122] and once this was done, the teeth were blackened by applying a dye called ohaguro.[123] The reason for blackening the teeth was that white teeth was a sign of distinction, so applying a dye to darken them was a desecration.[123] The heads were carefully arranged on a table for exposure.[122]

In 1600, Kani Saizō participated in the Battle of Sekigahara as the forerunner of Fukushima Masanori's army.[124] In the outpost battle of Gifu Castle, he took the heads of 17 enemy soldiers, and was greatly praised by Tokugawa Ieyasu.[124] He fought with a bamboo stalk on his back and would mark the heads of his defeated enemies by putting bamboo leaves in their cut necks or mouths, since he could not carry every head.[124] Thus he gained the nickname Bamboo Saizo.[124]

During Toyotomi Hideyoshi's invasions of Korea, the number of severed heads of the enemies to be sent to Japan was such that for logistical reasons only the noses were sent. These were covered with salt and shipped in wooden barrels. These barrels were buried in a burial mound near the "Great Buddha" of Hideyoshi, where they remain today under the wrong name of mimizuka or "ear mound".[125]

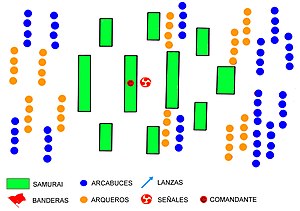

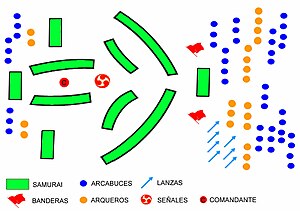

Military formations

During the Azuchi-Momoyama period and thanks to the introduction of firearms, combat tactics changed dramatically. The military formations adopted had poetic names, among which are:[126]

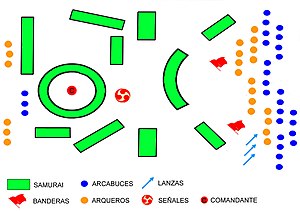

| Name | Description | Image |

|---|---|---|

| Ganko (birds in flight) |

A very flexible formation that allowed the troops to adapt depending on the movements of the opponent. The commander was located at the rear, but near the center to avoid communication problems. |

|

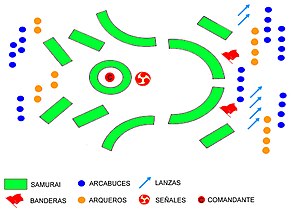

| Hoshi (arrowhead) |

An aggressive formation in which the samurai took advantage of the casualties caused by the shooting of the ashigaru. The signaling elements were close to the major generals of the commander. |

|

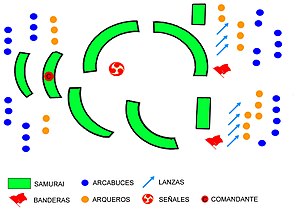

| Saku (lock) |

Considered the best defense against the Hoshi,[127] since two rows of arcabuceros and two archers were in position to receive the attack. |

|

| Kakuyoku (crane wings) |

Recurrent formation with the purpose of surrounding the enemy. The archers and arcabuceros diminished the enemy troops before the melee attack of the samurai while the second company surrounded them. |

|

| Koyaku (yoke) |

Owes its name to the yokes used for oxen. It was used to neutralize the "crane wings" and "arrowhead" attack and its purpose was for the vanguard to absorb the first attack and allow time for the enemy to reveal his next move to which the second company could react in time. |

|

| Gyōrin (fish scales) |

Frequently used to deal with much more numerous armies. Its purpose was to attack a single sector to break the enemy ranks. |

|

| Engetsu (half moon) |

Used when the army was not yet defeated but an orderly withdrawal to the castle was needed. While the rearguard receded, the vanguard could still be organized according to the circumstances. |

|

Myth and reality

Most samurai were bound by a code of honor and were expected to set an example for those below them. A notable part of their code is seppuku (切腹, seppuku) or hara kiri, which allowed a disgraced samurai to regain his honor by passing into death, where samurai were still beholden to social rules. While there are many romanticized characterizations of samurai behavior such as the writing of Bushido: The Soul of Japan in 1899, studies of kobudō and traditional budō indicate that the samurai were as practical on the battlefield as were any other warriors.[128]

Some writers take issue with the very mention of the term bushido when not used to describe an individual samurai's usage of the word because of how broad and changed the meaning of it has become over time.[129]

Despite the rampant romanticism of the 20th century, samurai could be disloyal and treacherous (e.g., Akechi Mitsuhide), cowardly, brave, or overly loyal (e.g., Kusunoki Masashige). Samurai were usually loyal to their immediate superiors, who in turn allied themselves with higher lords. These loyalties to the higher lords often shifted; for example, the high lords allied under Toyotomi Hideyoshi were served by loyal samurai, but the feudal lords under them could shift their support to Tokugawa, taking their samurai with them. There were, however, also notable instances where samurai would be disloyal to their lord (daimyō), when loyalty to the emperor was seen to have supremacy.[130]

In popular culture

Samurai figures have been the subject for legends, folk tales, dramatic stories (i.e. gunki monogatari), theatre productions in kabuki and noh, in literature, movies, animated and anime films, television shows, manga, video games, and in various musical pieces in genre that range from enka to J-Pop songs.

Jidaigeki (literally historical drama) has always been a staple program on Japanese movies and television. The programs typically feature a samurai. Samurai films and westerns share a number of similarities, and the two have influenced each other over the years. One of Japan's most renowned directors, Akira Kurosawa, greatly influenced western film-making. George Lucas' Star Wars series incorporated many stylistic traits pioneered by Kurosawa, and Star Wars: A New Hope takes the core story of a rescued princess being transported to a secret base from Kurosawa's The Hidden Fortress. Kurosawa was inspired by the works of director John Ford, and in turn Kurosawa's works have been remade into westerns such as Seven Samurai into The Magnificent Seven and Yojimbo into A Fistful of Dollars. There is also a 26-episode anime adaptation (Samurai 7) of Seven Samurai. Along with film, literature containing samurai influences are seen as well. As well as influence from American Westerns, Kurosawa also adapted two of Shakespeare's plays as sources for samurai movies: Throne of Blood was based on Macbeth, and Ran was based on King Lear.[131]