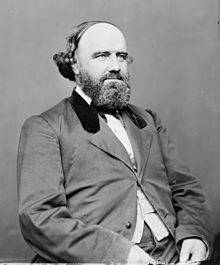

Samuel C. Pomeroy

Samuel C. Pomeroy | |

|---|---|

| |

| United States Senator from Kansas | |

| In office April 4, 1861 – March 3, 1873 | |

| Preceded by | None (statehood) |

| Succeeded by | John J. Ingalls |

| Member of the Massachusetts House of Representatives from Southampton | |

| In office 1852–1853 | |

| Preceded by | Chauncy Clapp |

| Succeeded by | Vacant |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Samuel Clarke Pomeroy January 3, 1816 Southampton, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | August 27, 1891 (aged 75) Whitinsville, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse(s) | Lucy Gaylord (m. April 23, 1846–1863 her death), Martha Stanwood Mann Whiting (m. September 20, 1866–1891) |

| Education | Amherst College |

| Profession | Politician, Teacher, Railroad President |

Samuel Clarke Pomeroy (January 3, 1816 – August 27, 1891) was a United States senator from Kansas in the mid-19th century. He served in the United States Senate during the American Civil War.[1] Pomeroy also served in the Massachusetts House of Representatives. A Republican, he also was the mayor of Atchison, Kansas, from 1858 to 1859,[1] the second president of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad, and the first president to oversee any of the railroad's construction and operations. Pomeroy succeeded Cyrus K. Holliday as president of the railroad on January 13, 1864.[2]

Career

[edit]Early life

[edit]Samuel C. Pomeroy was born on January 3, 1816, at Southampton, Massachusetts. He attended Amherst College.[3] Pomeroy opposed the politics of slavery, and in 1854 he became an affiliate of the New England Emigrant Aid Company. That fall, he led a group of settlers to Kansas to help found the city of Lawrence.[3][4]

1860s

[edit]On April 4, 1861, the Kansas legislature elected Pomeroy (along with James Lane) to be one of Kansas's first federal senators.[3][5] In 1863, during the Civil War, Pomeroy escorted Frederick Douglass to the War Department building to meet War Secretary Edwin Stanton. Afterwards, Douglass attended a meeting with President Abraham Lincoln.[6]

In 1862, Pomeroy was a supporter of Linconia, a plan to resettle freed African Americans from the United States.[7]

In 1864, Pomeroy was the chair of a committee supporting Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase for the Republican nomination for President of the United States over the incumbent, Abraham Lincoln.[8] Pomeroy also spoke in support of Chase's candidacy in the Senate.[9] The Pomeroy committee issued a confidential circular to leading Republicans in February 1864 attacking Lincoln, which had the unintended effect of galvanizing support for Lincoln and seriously damaging Chase's prospects.[8]

1870s

[edit]On December 18, 1871, at the urging of Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden and after learning of the findings of the Hayden Geological Survey of 1871, Pomeroy introduced the Act of Dedication bill into the Senate that ultimately led to the creation of Yellowstone National Park.[10]

1880s

[edit]During the 1880 presidential election Pomeroy was John W. Phelps' running mate on the revived Anti-Masonic Party.

Bribery charges

[edit]During the Kansas senatorial election of 1873, it was alleged that Senator Pomeroy paid $7,000 (~$162,100 in 2023) to Mr. Alexander M. York, a Kansas state senator, to secure his vote for reelection to the Senate by the Kansas State Legislature.[11] York publicly disclosed the alleged bribe was an attempt to pin a bribery charge against the senator.[12] After 19 ballots in the Kansas Legislature, Pomeroy was ultimately defeated when insiders turned to John J. Ingalls.[13]

Pomeroy took to the Senate floor on February 10, 1873, to deny the allegations as a "conspiracy ... for the purpose of accomplishing my defeat,"[11] and urged the creation of a special committee to investigate the allegations.[11] The payment of the $7,000 (~$162,100 in 2023) was never disputed by witnesses, but instead of being a bribe it was described to the committee as a payment meant to be passed along to a second individual as seed money to start a national bank.[14] The Special Committee on the Kansas Senatorial Election issued its report on March 3, 1873, which determined there was insufficient evidence to sustain the bribery charge, and instead was part of a "concerted plot" to defeat Senator Pomeroy.[14]

Senator Allen G. Thurman of Ohio disagreed with the special committee's findings, stating his belief in Pomeroy's guilt and calling attempts to explain the payment as something other than a bribe as "so improbable, especially in view of the circumstances attending the senatorial election, that reliance cannot be placed upon them."[14] However, Thurman chose not to pursue the matter further, as March 3 coincided with Senator Pomeroy's last day in office.[14] This whole matter was alluded to in detail in the satire The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today by Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner, in which the prominent character Senator Dillworth is based on Pomeroy.[15]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, 1774–Present". Retrieved July 5, 2005.

- ^ Waters, Lawrence Leslie (1950). Steel Trails to Santa Fe. University of Kansas Press, Lawrence, Kansas.

- ^ a b c Blackmar, Frank, ed. (1912). "Pomeroy, Samuel Clark". Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Embracing Events, Institutions, Industries, Counties, Cities, Towns, Prominent Persons, etc. Chicago, IL: Standard Publishing Company. pp. 485–86. Retrieved August 7, 2018.

- ^ Cordley, Richard (1895). A History of Lawrence, Kansas: From the Earliest Settlement to the Close of the Rebellion. Lawrence, KS: Lawrence Journal Press. pp. 6–7.

- ^ "Lane, James Henry, (1814 – 1866)". Biographical Dictionary of the United States Congress. United States Congress. Retrieved August 8, 2018.

- ^ "Grand Old Partisan: Commemorating the first meeting of Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln". Archived from the original on August 16, 2017. Retrieved August 16, 2017.

- ^ DiLorenzo, Thomas (2002). The Real Lincoln. New York: Three Rivers Press. p. 18. ISBN 0-7615-2646-3.

- ^ a b Goodwin, Doris Kearns (2005). Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln. Simon & Schuster, New York. pp. 605–07.

- ^ Congressional Globe. 38th Cong., 1st sess. March 10, 1864. 1025–27.

- ^ Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden and the Founding of the Yellowstone National Park. Washington, D.C.: United States Department of the Interior Geological Survey, U.S. Government Printing Office. 1973.

- ^ a b c Senate Journal. 42nd Cong., 3rd sess. 1214–1215.

- ^ Baker, Richard A. (2006), 200 Notable Days: Senate Stories 1787–2002, U.S. Government Printing Office, p. 106

- ^ "KANSAS SENATORIAL ELECTION.; Election of Mr. Ingalls--Attempted Bribery Alleged Against Mr. Pomeroy--His Arrest and Release on Bail". The New York Times.

- ^ a b c d Senate Journal. 42nd Cong., 3rd sess. March 3, 1873. 2161.

- ^ "Afterword" by Greg Camfield to the Oxford University Press edition of The Gilded Age, p.15.

External links

[edit] Media related to Samuel Clarke Pomeroy at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Samuel Clarke Pomeroy at Wikimedia Commons

- 1816 births

- 1891 deaths

- People from Southampton, Massachusetts

- American people of English descent

- Kansas Republicans

- Republican Party United States senators from Kansas

- Radical Republicans

- Republican Party members of the Massachusetts House of Representatives

- Mayors of places in Kansas

- 19th-century American railroad executives

- Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway presidents

- People from Atchison, Kansas

- Politically motivated migrations

- People of the American colonization movement

- Anti-Masonry

- Amherst College alumni

- People of Kansas in the American Civil War

- Union (American Civil War) political leaders