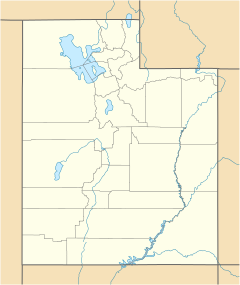

Saltair (Utah)

| Saltair | |

|---|---|

Saltair III Pavilion | |

| General information | |

| Status | Completed |

| Location | Great Salt Lake in Utah, United States |

| Coordinates | 40°44′49″N 112°11′17″W / 40.747029°N 112.187920°W |

Saltair, also The SaltAir, Saltair Resort, or Saltair Pavilion, is the name that has been given to several resorts located on the southern shore of the Great Salt Lake in Utah, United States, about 15 miles (24 km) from Salt Lake City.

History

[edit]Saltair I

[edit]

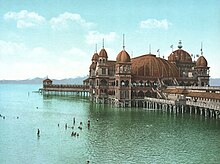

The first Saltair, completed in 1893, was jointly owned by a corporation associated with The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and Salt Lake & Los Angeles Railway (later renamed as the Salt Lake, Garfield, and Western Railway; not to be confused with the Los Angeles and Salt Lake Railroad), which was constructed for the express purpose of serving the resort.[1] Saltair was not the first resort built on the shores of the Great Salt Lake, but was the most successful ever built. A stunning example of early 20th century Moorish Revival architecture,[2] the resort was designed by well-known Utah architect Richard K.A. Kletting and rested on over 2,000 posts and pilings, many of which remain and still are visible over 110 years later.[3]

Intended from the beginning as the Western counterpart to Coney Island, Saltair was one of the early amusement parks, and for a time was the most popular family destination west of New York.[3] The church sold the resort in 1906.[4]

The first Saltair pavilion and a few other buildings were destroyed by fire on April 22, 1925.[4]

Saltair II

[edit]A new pavilion was built, and the resort was expanded at the same location by new investors, but several factors prevented the second Saltair from achieving the success of its ancestor. The advent of motion pictures and radio, the onset of the Great Depression, and the interruption of the "go to Saltair" routine kept people closer to home. With a huge new dance floor – the world's largest at the time –[4] Saltair became more known as a dance palace, the amusement park becoming secondary to the great traveling bands of the day, such as Glenn Miller. Though Saltair showed motion pictures, there were other theaters more convenient to town.

In addition, the first Saltair had benefited from its location on the road from Salt Lake City to the Tooele Valley and to Skull Valley, which in the late 1800s was home to Iosepa, a large community of Polynesian Mormons. Being near a major intersection, Saltair also served as the first (or last) major facility on the road, making it a popular resting area for those travelling by horseback or wagon. When Saltair was rebuilt, however, this traffic was all but gone. Part of the reason was the advent of automobiles, bus and train service to the Tooele Valley, but the other cause was the abandonment of Iosepa, as Polynesians went to homes in the Salt Lake Valley or the community forming around the new LDS Temple in Laie on Oahu in the Hawaiian Islands.

Saltair thus had to survive solely against strong competition, and in a dwindling market. Disaster struck in 1931, in the form of a fire that caused over $100,000 in damage, then again in 1933 as the resort was left high and dry when lake waters receded, forcing the construction of a miniature railway to carry swimmers between the resort and the water. Saltair was forced to close during World War II, which forced the rationing of fuel and other resources while it took many of the resort's paying customers – and vital employees – out of Utah. Reopening after the war, the resort found the same situation that it had faced in the 1930s. There were so many other entertainment options, closer to home, and the public was no longer in the habit of going "all the way out there". The resort closed in 1958, causing the railroad to cease passenger operations at the same time.[5]

Attempts over the next decade to breathe new life into the resort finally ended in November 1970 when an arson fire was set in the center of the wooden dance floor, destroying the main Saltair pavilion.[6][7] A previous arson fire in September 1967 had destroyed the concourse, entry gate, concession stands, and various other support structures but spared the main building.[8][1]

Saltair III

[edit]

Proximity to Interstate 80, plus new population expansion into the Tooele Valley and the western Salt Lake Valley, prompted the construction of a third Saltair in 1981.[9] The new pavilion was constructed out of a salvaged aircraft hangar from Hill Air Force Base, and located approximately a mile west of the original. Once again the lake was a problem, this time flooding the resort only months after it opened.[10] The waters again receded after several years, and again new investors restored and repaired and planned, only to discover that the waters continued to move away from the site, again leaving it high and dry.[11][12]

Concerts and other events have been held at the newest facility, but by the end of the 1990s, Saltair was little more than a memory, too small to compete with larger venues that were closer to the public. While there is occasionally activity now and then, through most of the early 21st century, the third Saltair was all but abandoned. In 2005 several investors from the music industry pooled together to purchase the building and are now holding regular concerts there.

Remnants

[edit]

Relics of the age of the Great Salt Lake resorts are nearby, and can be seen from the highway. Until recently, the most noticeable of these was the skeleton of car "502", one of the Salt Lake, Garfield & Western's interurban rail cars that sat beside the ruins of an old powerhouse.[13] The powerhouse once fed lights and roller coasters at the entrance to the original Saltair. The rail car was removed on February 18, 2012, by the property owner for safety concerns. Rows of pilings snake outward toward the lake, all that remains of the railway trestle and pier that once led to the earlier Saltair resort. The surviving buildings of Lake Park, one of Saltair's neighbors, were moved to a new site thirty miles away, where the Lagoon Amusement Park has grown around them.

The Salt Lake, Garfield & Western still exists as a common carrier shortline railroad, providing switching service in the Salt Lake City area. However, the tracks no longer reach to the resort itself.[5]

In popular culture

[edit]Saltair has occasionally been used as a backdrop for movies. Key scenes of the 1962 horror film Carnival of Souls were shot in Saltair II. The 1993 film Josh and S.A.M. features a scene at the then dilapidated Saltair III, showing the exterior and interior.

A photo session for the Beach Boys was held there in 1968 with various poses around Saltair II and was used in promotional materials as well as being featured on the cover of the bootleg Beach Boys album Unsurpassed Masters, Vol. 19.

The Saltair Pavilion is destroyed (along with much of Salt Lake City) by the eponymous creature in the 1972 underground independent film "The Giant Brine Shrimp" by Utah filmmaker Mike Cassidy.[14]

The Pixies's 1991 song "Palace of the Brine" is a reference to Saltair.[15]

The music video for Mac Miller's song "Stay" was filmed with Saltair III as the backdrop.[16]

Saltair was featured in the 2021 episode of the paranormal reality show Ghost Adventures, largely as a result of allegations of the building being haunted. The crew claimed to have filmed a shadow figure, disembodied voices, and several other paranormal occurrences.[17]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Carr, Stephen L. (1989). Utah Ghost Rails. Salt Lake City, Utah: Western Epics.

- ^ Utah Division of State History. "Saltair: A Photographic Exhibit". Retrieved 16 January 2023.

- ^ a b Utah State Historical Society. "Utah History to Go: Saltair". Retrieved 14 April 2011.

- ^ a b c Utah History Encyclopedia. "Saltair". Archived from the original on 1 May 2011. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

- ^ a b Strack, Don. "Salt Lake, Garfield & Western Railway". Retrieved 14 April 2011.

- ^ Monson, Jack; Starr, Curtis; Swenson, Paul (November 12, 1970). "Fire destroys historic Saltair resort". Deseret News. (Salt Lake City, Utah). p. B1.

- ^ "Saltair smolders, probe waits". Deseret News. (Salt Lake City, Utah). November 13, 1970. p. B1.

- ^ Knight, Hal; Blodgett, Gary (September 1, 1967). "Saltair is ravaged by arsonist blaze". Deseret News. (Salt Lake City, Utah). p. A1.

- ^ "Full Steam Ahead For Saltair Rec Area". The Transcript-Bulletin (Tooele, Utah). April 30, 1981. p. 1. Retrieved June 8, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Rolly, Paul (May 9, 1984). "Resort plagued by fire, rot and now floods". he Daily Spectrum (St. George, Utah). p. B6. Retrieved June 8, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ O'Brien, Joan (April 1, 1993). "Saltair Prepares For Reopening With Eye on Lake". The Salt Lake Tribune. p. B7. Retrieved June 8, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Borgenicht, Joe (July 6, 2000). "Like phoenix, Saltair ready again". The Transcript-Bulletin (Tooele, Utah). p. 12. Retrieved June 8, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "So long, Saltair Train: Iconic rail car makes final departure from Saltair". 18 February 2012.

- ^ 'The Giant Brine Shrimp' (Letterboxd)

- ^ Dan Nailen's Lounge Act: Pixies kill it at Saltair Archived 2014-05-11 at archive.today, Salt Lake Magazine

- ^ Stay, 'Mac Miller'

- ^ "The Great Saltair Curse". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 13 July 2023.