Mud volcano

A mud volcano or mud dome is a landform created by the eruption of mud or slurries, water and gases.[1][2][3] Several geological processes may cause the formation of mud volcanoes. Mud volcanoes are not true igneous volcanoes as they do not produce lava and are not necessarily driven by magmatic activity. Mud volcanoes may range in size from merely 1 or 2 meters high and 1 or 2 meters wide, to 700 meters high and 10 kilometers wide.[4] Smaller mud exudations are sometimes referred to as mud-pots.

The mud produced by mud volcanoes is mostly formed as hot water, which has been heated deep below the Earth's surface, begins to mix and blend with subterranean mineral deposits, thus creating the mud slurry exudate. This material is then forced upwards through a geological fault or fissure due to local subterranean pressure imbalances. Mud volcanoes are associated with subduction zones and about 1100 have been identified on or near land. The temperature of any given active mud volcano generally remains fairly steady and is much lower than the typical temperatures found in igneous volcanoes. Mud volcano temperatures can range from near 100 °C (212 °F) to occasionally 2 °C (36 °F), some being used as popular "mud baths".[citation needed]

About 86% of the gas released from these structures is methane, with much less carbon dioxide and nitrogen emitted. Ejected materials are most often a slurry of fine solids suspended in water that may contain a mixture of salts, acids and various hydrocarbons.[citation needed]

Possible mud volcanoes have been identified on Mars.[5]

Details

[edit]

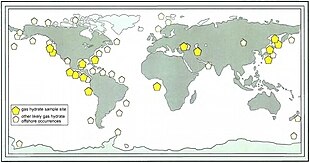

A mud volcano may be the result of a piercement structure created by a pressurized mud diapir that breaches the Earth's surface or ocean bottom. Their temperatures may be as low as the freezing point of the ejected materials, particularly when venting is associated with the creation of hydrocarbon clathrate hydrate deposits. Mud volcanoes are often associated with petroleum deposits and tectonic subduction zones and orogenic belts; hydrocarbon gases are often erupted. They are also often associated with lava volcanoes; in the case of such close proximity, mud volcanoes emit incombustible gases including helium, whereas lone mud volcanoes are more likely to emit methane.

Approximately 1,100 mud volcanoes have been identified on land and in shallow water. It has been estimated that well over 10,000 may exist on continental slopes and abyssal plains.

Features[citation needed]

[edit]- Gryphon: steep-sided cone shorter than 3 meters that extrudes mud

- Mud cone: high cone shorter than 10 meters that extrudes mud and rock fragments

- Scoria cone: cone formed by heating of mud deposits during fires

- Salse: water-dominated pools with gas seeps

- Spring: water-dominated outlets smaller than 0.5 metres

- Mud shield

Emissions

[edit]Deep Sea Mud Volcanoes

Mud volcanoes are regularly found along the subsurface seafloor, they are primarily responsible for releasing methane into the water column along with other gases and fluids. The high pressure and low temperature associated with the bottom of the seafloor, can be the predominant cause of why gases and fluids get trapped that are rising upward, this is a result of methane oversaturation. The total methane emission of offshore mud volcanoes is about 27 Tg per year.[6] This estimate does come with uncertainties, such as the total number of mud volcanoes and their release of methane into the atmosphere/water column is unknown.

Surface Mud Volcanoes

Most liquid and solid material is released during eruptions, but seeps occur during dormant periods. The chemical composition of mud volcanoes is almost entirely methane and hydrocarbons found within the mud and the shale from the mud volcanoes.[7] The emissions from mud volcanoes can be entirely dependent on its location, mud volcanoes from NW China are more enriched with methane and have lower concentrations of propane and ethane.[8] The origin of the gas is most likely from below 5000m in the Earth's crust.

Most liquid and solid material is released during eruptions, but seeps occur during dormant periods.

The mud is rich in halite (rock salt).[citation needed] The overall chemical composition of mud volcanoes is similar to normal magma concentrations. The content of the mud volcano from Kampun Meritam, Limbang are 59.51 weight percent (wt. %) SiO2, 0.055 wt.% MnO, and 1.84 wt.% MgO.

First-order estimates of mud volcano emissions have been made (1 Tg = 1 million metric tonnes).

- 2002: L. I. Dimitrov estimated that 10.2–12.6 Tg/yr of methane is released from onshore and shallow offshore mud volcanoes.

- 2002: Etiope and Klusman estimated at least 1–2 and as much as 10–20 Tg/yr of methane may be emitted from onshore mud volcanoes.

- 2003: Etiope, in an estimate based on 120 mud volcanoes: "The emission results to be conservatively between 5 and 9 Tg/yr, that is 3–6% of the natural methane sources officially considered in the atmospheric methane budget. The total geologic source, including MVs (this work), seepage from seafloor (Kvenvolden et al., 2001), microseepage in hydrocarbon-prone areas and geothermal sources (Etiope and Klusman, 2002), would amount to 35–45 Tg/yr."[9]

- 2003: analysis by Milkov et al. suggests that the global gas flux may be as high as 33 Tg/yr (15.9 Tg/yr during quiescent periods plus 17.1 Tg/yr during eruptions). Six teragrams per year of greenhouse gases are from onshore and shallow offshore mud volcanoes. Deep-water sources may emit 27 Tg/yr. Total may be 9% of fossil CH4 missing in the modern atmospheric CH4 budget, and 12% in the preindustrial budget.[10]

- 2003: Alexei Milkov estimated approximately 30.5 Tg/yr of gases (mainly methane and CO2) may escape from mud volcanoes to the atmosphere and the ocean.[11]

- 2003: Achim J. Kopf estimated 1.97×1011 to 1.23×1014 m³ of methane is released by all mud volcanoes per year, of which 4.66×107 to 3.28×1011 m³ is from surface volcanoes.[12] That converts to 141–88,000 Tg/yr from all mud volcanoes, of which 0.033–235 Tg is from surface volcanoes.

Locations

[edit]Europe

[edit]

Dozens of mud volcanoes are located on the Taman Peninsula of Russia and the Kerch Peninsula of Crimea, Ukraine along with the south-western portion of Bulgaria near Rupite. In Italy, they are located in Emilia-Romagna (Salse di Nirano and Salse di Regnano), in the northern front of the Apennines as well as the southern part (Bolle della Malvizza), and in Sicily. On 24 August 2013, a mud volcano appeared in the center of the via Coccia di Morto roundabout in Fiumicino near Rome.[13][14]

Mud volcanoes are located in the Berca Mud Volcanoes near Berca in Buzău County, Romania, close to the Carpathian Mountains.[15] They were declared a natural monument in 1924.

Asia

[edit]Central Asia, The Caucasus, and The Caspian Sea

[edit]Many mud volcanoes exist on the shores of the Black Sea and Caspian Sea. Tectonic forces and large sedimentary deposits around the latter have created several fields of mud volcanoes, many of them emitting methane and other hydrocarbons. Features over 200 metres (656 ft) high occur in Azerbaijan, with large eruptions sometimes producing flames of similar scale.[citation needed]

Georgia

[edit]There are mud volcanoes in Georgia, such as the one at Akhtala.[16]

Turkmenistan

[edit]

Turkmenistan is home to numerous mud volcanoes, mainly in the western part of the country including Cheleken Peninsula, which borders the Caspian Sea.[17]

Iran and Pakistan (Makran Mountain Range)

[edit]Iran and Pakistan possess mud volcanoes in the Makran range of mountains in the south of the two countries. A large mud volcano is located in Balochistan, Pakistan. It is known as Baba Chandrakup (literally Father Moonwell) on the way to Hinglaj and is a Hindu pilgrim site.[18]

Azerbaijan

[edit]

Azerbaijan and its Caspian coastline are home to nearly 400 mud volcanoes, more than half the total throughout the continents.[19] Most mud volcanoes in Azerbaijan are active; some are protected by the Azerbaijan Ministry of Ecology and Natural Resources, and the admission of people, for security reasons, is prohibited.[20] In 2001, one mud volcano 15 kilometres (9 mi) from Baku made world headlines when it started ejecting flames 15 metres (49 ft) high.[21]

In Azerbaijan, eruptions are driven from a deep mud reservoir which is connected to the surface even during dormant periods, when seeping water shows a deep origin. Seeps have temperatures that are generally above ambient ground temperature by 2 °C (3.6 °F) – 3 °C (5.4 °F).[22]

On 4 July 2021, a mud volcano eruption on Dashli Island in the Caspian Sea, near an oil platform off the coast of Azerbaijan, caused a massive explosion and fireball, which was seen across the region, including from the capital Baku, which is 74 kilometres (46 mi) to the north. The flames towered 500 metres (1,640 ft) into the air.[23][24][25] There were no reports of injuries or damage to any oil platforms.[26] The last previous volcanic eruption on the island was recorded in 1945 and the preceding one in 1920.[27]

India

[edit]Extensive mud volcanism occurs on the Andaman accretionary prism, located at the Andaman Islands in the Indian Ocean.[28]

Indonesia

[edit]

Mud volcanism is a common phenomenon in Indonesia with dozens of structures present onshore and offshore.[29][30]

The Indonesian Lusi mud eruption is a hybrid mud volcano, driven by pressure from steam and gas from a nearby (igneous) volcanic system, and from natural gas. Geochemical, petrography and geophysical results reveal that it is a sediment-hosted[clarification needed] hydrothermal system connected at depth with the neighboring Arjuno-Welirang volcanic complex.[31][32][33][34][35]

Drilling or an earthquake[36][30] in the Porong subdistrict of East Java province, Indonesia, may have resulted in the Sidoarjo mud flow on 29 May 2006.[37][38][39] The mud covered about 440 hectares, 1,087 acres (4.40 km2) (2.73 mi2), and inundated four villages, homes, roads, rice fields, and factories, displacing about 24,000 people and killing 14. The gas exploration company involved was operated by PT Lapindo Brantas and the earthquake that may have triggered the mud volcano was the 6.4 magnitude[citation needed] Yogyakarta earthquake of 27 May 2006. According to geologists who have been monitoring Lusi and the surrounding area, the system is beginning to show signs of catastrophic collapse. It was forecast that the region could sag the vent and surrounding area by up to 150 metres (490 ft) in the next decade. In March 2008, the scientists observed drops of up to 3 metres (9.8 ft) in one night. Most of the subsidence in the area around the volcano is more gradual, at around 1 millimetre (0.039 in) per day. A study by a group of Indonesian geoscientists led by Bambang Istadi predicted the area affected by the mudflow over a ten-year period.[40] More recent studies carried out in 2011 predict that the mud will flow for another 20 years, or even longer.[41] Now named Lusi – a contraction of Lumpur Sidoarjo, where lumpur is the Indonesian word for "mud" – the eruption represent an active hybrid system.

In the Suwoh depression in Lampung, dozens of mud cones and mud pots varying in temperature are found.[citation needed]

In Grobogan, Bledug Kuwu mud volcano erupts at regular intervals,[42] about every 2 or 3 minutes.

Iran

[edit]

There are many mud volcanoes in Iran: in particular, in the provinces of Golestan, Hormozgan, and Sistan and Baluchestan, where Pirgel is located.

Mariana Forearc

[edit]There are 10 active mud volcanoes in the Izu–Bonin–Mariana Arc which can be found along a north to south trend, parallel to the Mariana trench.[43] The material erupted at these mud volcanoes consists primarily of blue and green serpentinite mud which contains fresh and serpentinized peridotite material from the subduction channel. Fluid from the descending Pacific Plate is released by dehydration and alteration of rocks and sediment.[43] This fluid interacts with mafic and ultramafic rocks in the descending Pacific Plate and overriding Philippine Plate, resulting in the formation of serpentinite mud.[44] All of these mud volcanoes are associated with faults, indicating that the faults act as conduits for the serpentine mud to migrate from the subduction channel to the surface.[43] These mud volcanoes are large features on the forearc, the largest of which has a diameter of ~50 kilometres (31 mi) and is over 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) high.

Pakistan

[edit]

In Pakistan there are more than 130 active mud volcanoes or vents in Balochistan province; there are about 10 locations with clusters of mud volcanoes. In the west, in Gwadar District, the mud volcanoes are very small and mostly sit in the south of Jabal-e-Mehdi toward Sur Bandar. Many more are in the northeast of Ormara. The remainder are in Lasbela District and are scattered between south of Gorangatti on Koh Hinglaj to Koh Kuk in the North of Miani Hor in the Hangol Valley. In this region, the heights of mud volcanoes range between 300 and 2,600 feet (91.4 and 792.5 m). [citation needed] The most famous is Chandragup. The biggest crater is of V15 mud volcano found at 25°33'13.63"N. 65°44'09.66"E is about 450 feet (137.16 m) in diameter. Most mud volcanoes in this region are in out-of-reach areas having very difficult terrain. Mount Mehdi mud volcano near Miani Hor is also famous for large mud glacier around its caldera. Dormant mud volcanoes stand like columns of mud in many other areas.[citation needed]

Philippines

[edit]In the Turtle Islands, in the province of Tawi-Tawi, the southwestern edge of the Philippines bordering Malaysia, presence of mud volcanoes are evident on three of the islands – Lihiman, Great Bakkungan and Boan Islands. The northeastern part of Lihiman Island is distinguished for having a more violent kind of mud extrusions mixed with large pieces of rocks, creating a 20-m (66-ft) wide crater on that hilly part of the island.[45] Such extrusions are reported to be accompanied by mild earthquakes and evidence of extruded materials can be found high in the surrounding trees. Submarine mud extrusions off the island have been observed by local residents.[46]

Other Asian locations

[edit]

- There are a number of mud volcanoes in Xinjiang.

- There are mud volcanoes at Minbu Township, Magway Region, Myanmar (Burma). There is a local belief that these mud volcanoes are the refuge of mythological Nāga.

- There are two active mud volcanoes in southern Taiwan and several inactive ones. The Wushan Mud Volcanoes are in the Yanchao District of Kaohsiung City. There are active mud volcanoes in Wandan township of Pingtung County.

- There are mud volcanoes on the island of Pulau Tiga, off the western coast of the Malaysian state of Sabah on Borneo.

- The Meritam Volcanic Mud, locally called the 'lumpur bebuak', located about 35 kilometres (22 mi) from Limbang, Sarawak, Malaysia is a tourist attraction.[47]

- A drilling accident offshore of Brunei on Borneo in 1979 caused a mud volcano which took 20 relief wells and nearly 30 years to halt.

- Active mud volcanoes occur in Oesilo (Oecusse District, East Timor). A mud volcano in Bibiluto (Viqueque District) erupted between 1856 and 1879.[48]

North America

[edit]

Mud volcanoes of the North American continent include:

- A field of small (<2 metres (6.6 ft) high) fault-controlled, cold mud volcanoes is on California's Mendocino Coast, near Glenblair and Fort Bragg, California. The fine-grained clay is occasionally harvested by local potters.[49]

- Shrub and Klawasi mud volcanoes in the Copper River basin by the Wrangell Mountains, Alaska. Emissions are mostly CO2 and nitrogen; the volcanoes are associated with magmatic processes.

- An unnamed mud volcano 30 metres (98 ft) high and with a top about 100 metres (328 ft) wide, 24 kilometres (15 mi) off Redondo Beach, California, and 800 metres (2,620 ft) under the surface of the Pacific Ocean.

- A field of small (<3 metres (9.8 ft)) mud volcanoes in the Salton Sea geothermal area near the town of Niland, California.[50] Emissions are mostly CO2. One, known as the Niland Geyser, continues to move erratically.[51]

- Smooth Ridge mud volcano in 1,000 metres (3,280 ft) of water near Monterey Canyon, California.

- Kaglulik mud volcano, 43 metres (141 ft) under the surface of the Beaufort Sea, near the northern boundary of Alaska and Canada. Petroleum deposits are believed to exist in the area.

- Maquinna mud volcano, located 16–18 kilometres (9.9–11.2 mi) west of Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada.

Yellowstone's "Mud Volcano"

[edit]

The name of Yellowstone National Park's "Mud Volcano" feature and the surrounding area is misleading; it consists of hot springs, mud pots and fumaroles, rather than a true mud volcano. Depending upon the precise definition of the term mud volcano, the Yellowstone formation could be considered a hydrothermal mud volcano cluster. The feature is much less active than in its first recorded description, although the area is quite dynamic. Yellowstone is an active geothermal area with a magma chamber near the surface, and active gases are chiefly steam, carbon dioxide, and hydrogen sulfide.

However, there are mud volcanoes and mud geysers elsewhere in Yellowstone.[52] One, the "Vertically Gifted Cyclic Mud Pot" sometimes acts as a geyser, throwing mud up to 30 feet high.

The mud volcano feature in Yellowstone was previously a mound until a thermal explosion in the 1800s ripped it apart.[53][page needed]

Caribbean

[edit]

There are many mud volcanoes in Trinidad and Tobago in the Caribbean, near oil reserves in southern parts of the island of Trinidad. As of 15 August 2007, the mud volcano titled the Moruga Bouffle was said to being spitting up methane gas which shows that it is active. There are several other mud volcanoes in the tropical island which include:

- the Devil's Woodyard mud volcano near New Grant, Princes Town, Trinidad and Tobago

- the Moruga Bouffe mud volcano near Moruga

- the Digity mud volcano in Barrackpore

- the Piparo mud volcano

- the Chatham mud volcano underwater in the Columbus Channel; this mud volcano periodically produces a short-lived island.

- the Erin Bouffe mud volcano near Los Iros beach

- L'eau Michel mud volcano in Bunsee Trace, Penal

A number of large mud volcanoes have been identified on the Barbados accretionary complex, offshore Barbados.[54]

South America

[edit]Venezuela

[edit]

The eastern part of Venezuela contains several mud volcanoes (or mud domes), all of them having an origin related to oil deposits. The mud of 6 kilometres (3.7 mi) from Maturín, contains water, biogenic gas, hydrocarbons and an important quantity of salt. Cattle from the savanna often gather around to lick the dried mud for its salt content.[citation needed]

Colombia

[edit]Volcan El Totumo,[55] which marks the division between Bolívar and Atlantico in Colombia. This volcano is approximately 50 feet (15 m) high and can accommodate 10 to 15 people in its crater; many tourists and locals visit this volcano due to the alleged medicinal benefits of the mud; it is next to a cienaga, or lake. This volcano is under legal dispute between the Bolívar and Atlántico Departamentos because of its tourist value.[citation needed]

Africa

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (March 2023) |

Australasia

[edit]New Zealand

[edit]As well as the Runaruna Mud Volcano the size of the splatter cones associated with some of New Zealands many geothermal mud pools or mudpots might qualify, depending upon definition.

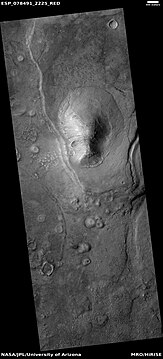

Possible mud volcanoes on Mars

[edit]-

Wide view of field of mud volcanoes, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

-

Close view of mud volcanoes, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

-

Close view of mud volcanoes and boulders, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

-

Wide view of mud volcanoes, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

-

Close view of mud volcanoes, as seen by HiRISE

-

Close view of mud volcanoes, as seen by HiRISE Low area around the volcanoes contains transverse aeolian ridges (TAR's). Only part of picture is in color because HiRISE only takes a color strip in middle of image.

-

Close view of mud volcano, as seen by HiRISE. Picture is about 1 km across. This mud volcano has a different color than the surroundings because it consists of material brought up from depth. These structures may be useful to explore for remains of past life since they contain samples that would have been protected from the strong radiation at the surface.

See also

[edit]- Asphalt volcano

- Black smoker

- Cold seep

- Hydrothermal vent

- Ice volcano

- Lahar – mud flow

- Methane hydrate

- Sand volcano

- Seamount

- Volcano – igneous volcano

References

[edit]- ^ Mazzini, Adriano; Etiope, Giuseppe (May 2017). "Mud volcanism: An updated review". Earth-Science Reviews. 168: 81–112. Bibcode:2017ESRv..168...81M. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2017.03.001. hdl:10852/61234.

- ^ Kopf, Achim J. (2002). "Significance of mud volcanism". Reviews of Geophysics. 40 (2): 1005. Bibcode:2002RvGeo..40.1005K. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.708.2270. doi:10.1029/2000rg000093. S2CID 21707159.

- ^ Dimitrov, Lyobomir I (November 2002). "Mud volcanoes—the most important pathway for degassing deeply buried sediments". Earth-Science Reviews. 59 (1–4): 49–76. Bibcode:2002ESRv...59...49D. doi:10.1016/s0012-8252(02)00069-7.

- ^ Kioka, Arata; Ashi, Juichiro (28 October 2015). "Episodic massive mud eruptions from submarine mud volcanoes examined through topographical signatures". Geophysical Research Letters. 42 (20): 8406–8414. Bibcode:2015GeoRL..42.8406K. doi:10.1002/2015GL065713.

- ^ "Mars domes may be 'mud volcanoes'". BBC. March 26, 2009. Retrieved 2009-03-27.

- ^ Feseker, Tomas; Boetius, Antje; Wenzhöfer, Frank; Blandin, Jerome; Olu, Karine; Yoerger, Dana R.; Camilli, Richard; German, Christopher R.; de Beer, Dirk (2014-11-11). "Eruption of a deep-sea mud volcano triggers rapid sediment movement". Nature Communications. 5 (1): 5385. Bibcode:2014NatCo...5.5385F. doi:10.1038/ncomms6385. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 4242465. PMID 25384354.

- ^ Yussibnosh, Jossiana binti; Mohan Viswanathan, Prasanna; Modon Valappil, Ninu Krishnan (2023-06-01). "Geochemical evaluation of mud volcanic sediment and water in Northern Borneo: A baseline study". Total Environment Research Themes. 6: 100033. Bibcode:2023TERT....600033Y. doi:10.1016/j.totert.2023.100033. ISSN 2772-8099.

- ^ Xu, Wang; Zheng, Guodong; Ma, Xiangxian; Fortin, Danielle; Fu, Ching Chou; Li, Qi; Chelnokov, Georgy Alekseevich; Ershov, Valery (2022-01-01). "Chemical and isotopic features of seepage gas from mud volcanoes in southern margin of the Junggar Basin, NW China". Applied Geochemistry. 136: 105145. Bibcode:2022ApGC..13605145X. doi:10.1016/j.apgeochem.2021.105145. ISSN 0883-2927.

- ^ Etiope, Giuseppe; Milkov, Alexei V. (November 2004). "A new estimate of global methane flux from onshore and shallow submarine mud volcanoes to the atmosphere". Environmental Geology. 46 (8): 997–1002. doi:10.1007/s00254-004-1085-1. S2CID 140564320. ProQuest 618713361.

- ^ Milkov, Alexei V.; Sassen, Roger; Apanasovich, Tatiyana V.; Dadashev, Farid G. (January 2003). "Global gas flux from mud volcanoes: A significant source of fossil methane in the atmosphere and the ocean". Geophysical Research Letters. 30 (2): 1037. Bibcode:2003GeoRL..30.1037M. doi:10.1029/2002GL016358.

- ^ Milkov, Alexei V.; Sassen, Roger (May 2003). Global Distribution and Significance of Mud Volcanoes. AAPG Annual Convention.

- ^ Kopf, Achim J. (1 October 2003). "Global methane emission through mud volcanoes and its past and present impact on the Earth's climate". International Journal of Earth Sciences. 92 (5): 806–816. Bibcode:2003IJEaS..92..806K. doi:10.1007/s00531-003-0341-z. S2CID 195334765.

- ^ "Mini volcano pops up in Rome". Euronews. 28 August 2013.

- ^ Costantini, Valeria (27 August 2013). "Il mini- vulcano con eruzioni fino a tre metri" [The mini-volcano with eruptions of up to three metres]. Corriere della Sera Roma (in Italian).

- ^ "Vulcanii Noroioși – Consiliul Județean Buzău" (in Romanian). Retrieved 2021-05-27.

- ^ Koiava, Kakhaber (October 2016). "The Structure and Geochemistry of the Kila-Kupra Mud Volcano (Georgia)". Vakhtang Bacho Glonti: 2 – via Research Gate.

- ^ Oppo, Davide (November 2014). "Mud volcanism and fluid geochemistry in the Cheleken Peninsula, western Turkmenistan". Marine and Petroleum Geology. 57: 122–134. Bibcode:2014MarPG..57..122O. doi:10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2014.05.009 – via Research Gate.

- ^ "Mud Volcanoes of Balochistan". 2007-03-02. Archived from the original on 2012-09-15. Retrieved 2009-08-13.

- ^ "MUD VOLCANOES OF AZERBAIJAN". www.atlasobscura.com. Retrieved 29 August 2014.

- ^ "Azerbaijan kicks off project to research mud volcanoes scientifically". Azernews.Az. 2022-07-18. Retrieved 2022-07-19.

- ^ "Azeri mud volcano flares". BBC News. October 29, 2001. Retrieved May 13, 2010.

- ^ Planke, S.; Svensen, H.; Hovland, M.; Banks, D. A.; Jamtveit, B. (1 December 2003). "Mud and fluid migration in active mud volcanoes in Azerbaijan". Geo-Marine Letters. 23 (3–4): 258–268. Bibcode:2003GML....23..258P. doi:10.1007/s00367-003-0152-z. S2CID 128779712.

- ^ "Azerbaijan Mud Volcano Erupts in Fiery Display". Smithsonian Magazine. 2021-07-07. Retrieved 2021-07-07.

- ^ "Press conference on incident in the Caspian Sea-VIDEO". Apa.az. Retrieved 2021-07-05.

- ^ "Azerbaijan says "mud volcano" caused Caspian Sea explosion". The Guardian. 2021-07-05. Retrieved 2021-07-05.

- ^ "Mud volcano causes large explosion in the Caspian Sea". BNO News. 4 July 2021.

- ^ "Mud volcanoes explained as huge explosion rocks the oil-rich Caspian Sea". Newsweek. 2021-07-05. Retrieved 2021-07-05.

- ^ Ray, Jyotiranjan S.; Kumar, Alok; Sudheer, A.K.; Deshpande, R.D.; Rao, D.K.; Patil, D.J.; Awasthi, Neeraj; Bhutani, Rajneesh; Bhushan, Ravi; Dayal, A.M. (June 2013). "Origin of gases and water in mud volcanoes of Andaman accretionary prism: implications for fluid migration in forearcs". Chemical Geology. 347: 102–113. Bibcode:2013ChGeo.347..102R. doi:10.1016/j.chemgeo.2013.03.015.

- ^ Satyana, A.H. (1 May 2008). "Mud diapirs and mud volcanoes in depressions of Java to Madura : origins, natures, and implications to petroleum system". Proc. Indon Petrol. Assoc., 32nd Ann. Conv. doi:10.29118/ipa.947.08.g.139.

- ^ a b Mazzini, A.; Nermoen, A.; Krotkiewski, M.; Podladchikov, Y.; Planke, S.; Svensen, H. (November 2009). "Strike-slip faulting as a trigger mechanism for overpressure release through piercement structures. Implications for the Lusi mud volcano, Indonesia". Marine and Petroleum Geology. 26 (9): 1751–1765. Bibcode:2009MarPG..26.1751M. doi:10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2009.03.001.

- ^ Mazzini, Adriano; Scholz, Florian; Svensen, Henrik H.; Hensen, Christian; Hadi, Soffian (February 2018). "The geochemistry and origin of the hydrothermal water erupted at Lusi, Indonesia". Marine and Petroleum Geology. 90: 52–66. Bibcode:2018MarPG..90...52M. doi:10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2017.06.018. hdl:10852/61230.

- ^ Inguaggiato, Salvatore; Mazzini, Adriano; Vita, Fabio; Sciarra, Alessandra (February 2018). "The Arjuno-Welirang volcanic complex and the connected Lusi system: Geochemical evidences". Marine and Petroleum Geology. 90: 67–76. Bibcode:2018MarPG..90...67I. doi:10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2017.10.015.

- ^ Malvoisin, Benjamin; Mazzini, Adriano; Miller, Stephen A. (September 2018). "Deep hydrothermal activity driving the Lusi mud eruption". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 497: 42–49. Bibcode:2018E&PSL.497...42M. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2018.06.006. S2CID 135102629.

- ^ Mazzini, Adriano; Etiope, Giuseppe; Svensen, Henrik (February 2012). "A new hydrothermal scenario for the 2006 Lusi eruption, Indonesia. Insights from gas geochemistry". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 317–318: 305–318. Bibcode:2012E&PSL.317..305M. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2011.11.016.

- ^ Fallahi, Mohammad Javad; Obermann, Anne; Lupi, Matteo; Karyono, Karyono; Mazzini, Adriano (October 2017). "The Plumbing System Feeding the Lusi Eruption Revealed by Ambient Noise Tomography: The Plumbing System Feeding Lusi". Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth. 122 (10): 8200–8213. doi:10.1002/2017jb014592. hdl:10852/61236. S2CID 133631006.

- ^ Mazzini, A.; Svensen, H.; Akhmanov, G.G.; Aloisi, G.; Planke, S.; Malthe-Sørenssen, A.; Istadi, B. (September 2007). "Triggering and dynamic evolution of the LUSI mud volcano, Indonesia". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 261 (3–4): 375–388. Bibcode:2007E&PSL.261..375M. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2007.07.001.

- ^ Davies, Richard J.; Brumm, Maria; Manga, Michael; Rubiandini, Rudi; Swarbrick, Richard; Tingay, Mark (August 2008). "The East Java mud volcano (2006 to present): An earthquake or drilling trigger?". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 272 (3–4): 627–638. Bibcode:2008E&PSL.272..627D. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2008.05.029.

- ^ Sawolo, Nurrochmat; Sutriono, Edi; Istadi, Bambang P.; Darmoyo, Agung B. (November 2009). "The LUSI mud volcano triggering controversy: Was it caused by drilling?". Marine and Petroleum Geology. 26 (9): 1766–1784. Bibcode:2009MarPG..26.1766S. doi:10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2009.04.002.

- ^ Sawolo, Nurrochmat; Sutriono, Edi; Istadi, Bambang P.; Darmoyo, Agung B. (August 2010). "Was LUSI caused by drilling? – Authors reply to discussion". Marine and Petroleum Geology. 27 (7): 1658–1675. Bibcode:2010MarPG..27.1658S. doi:10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2010.01.018.

- ^ Istadi, Bambang P.; Pramono, Gatot H.; Sumintadireja, Prihadi; Alam, Syamsu (November 2009). "Modeling study of growth and potential geohazard for LUSI mud volcano: East Java, Indonesia". Marine and Petroleum Geology. 26 (9): 1724–1739. Bibcode:2009MarPG..26.1724I. doi:10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2009.03.006.

- ^ Normile, Dennis (24 February 2011). "Indonesia's Infamous Mud Volcano Could Outlive All of Us". Science. AAAS.

- ^ Nugroho, Puthut Dwi Putranto (15 July 2017). "Bledug Kuwu, Fenomena Letupan Lumpur Unik di Jawa Tengah". kompas.com (in Indonesian). Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ a b c Fryer, P.; Wheat, C.G.; Williams, T.; Expedition 366 Scientists (2017-11-06). International Ocean Discovery Program Expedition 366 Preliminary Report. International Ocean Discovery Program Preliminary Report. International Ocean Discovery Program. doi:10.14379/iodp.pr.366.2017.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Fryer, P.; Wheat, C. G.; Mottl, M. J. (1999). <0103:mbmvif>2.3.co;2 "Mariana blueschist mud volcanism: Implications for conditions within the subduction zone". Geology. 27 (2): 103. Bibcode:1999Geo....27..103F. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1999)027<0103:mbmvif>2.3.co;2. ISSN 0091-7613.

- ^ "Geo-physical Features of Philippine Turtle Island". Ocean Ambassadors Track a Turtle. Retrieved on 2010-10-05.

- ^ "Lihiman Island". Ocean Ambassadors Track a Turtle. Retrieved on 2010-10-05.

- ^ Sheblee, Zulazhar (11 October 2017). "'Volcanoes' pull in the crowd". The Star.

- ^ Sammlungen des Geologischen Reichsmuseums in Leiden, Arthur Wichmann: Gesteine von Timor und einiger angrenzenden Inseln. Leiden, E. J. Brill, 1882–1887 1, Bände 10–11, S. 165

- ^ "Discover northern california". Independent Travel Tours. Archived from the original on 10 October 2008. Retrieved 25 February 2010.

- ^ Howser, Huell (September 7, 2009). "Desert Adventures – California's Gold Special (142)". California's Gold. Chapman University Huell Howser Archive. Archived from the original on June 24, 2013.

- ^ Geggel, Laura (2 November 2018). "A Gurgling Mud Pool Is Creeping Across Southern California Like a Geologic Poltergeist". Live Science.

- ^ "Mud volcano". USGS Photo glossary of volcano terms. Archived from the original on April 4, 2005. Retrieved April 20, 2005.

- ^ Whittlesey, Lee (1995) [1995]. Death in Yellowstone: Accidents and Foolhardiness in the First National Park. Lanham, Maryland: Roberts Rinehart Publishers. ISBN 978-1-57098-021-3.

- ^ Barnard, A.; Sager, W. W.; Snow, J. E.; Max, M. D. (2015-06-01). "Subsea gas emissions from the Barbados Accretionary Complex". Marine and Petroleum Geology. 64: 31–42. Bibcode:2015MarPG..64...31B. doi:10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2015.02.008.

- ^ "Student Travel Information & Discounts - Events: Volcán de Lodo el Totumo (Mud Volcano) (Volcan de Lodo el Totumo, Colombia)". Archived from the original on 2007-10-07. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

External links

[edit]- Origin of mud volcanoes

- Cold water mud volcanoes created by artesian pressure in Minnesota's Nemadji River basin

- Bulletin Of Mud Volcanology Azerbaijan Academy Of Sciences (in English)

- Gaia's Breath—Methane and the Future of Natural Gas Archived 2009-02-12 at the Wayback Machine – USGS, June 2003

- Azeri mud volcano flares – October 29, 2001, BBC report

- Redondo Beach mud volcano with methane hydrate deposits

- Hydrocarbons Associated with Fluid Venting Process in Monterey Bay, California

- Hydrothermal Activity and Carbon-Dioxide Discharge at Shrub and Upper Klawasi Mud Volcanoes, Wrangell Mountains, Alaska – U.S. Geological Survey Water-Resources Investigations Report 00-4207

- Mud Volcano Eruption at Baratang, Middle Andamans

- Article on mud volcanoes from Azerbaijan International

- Mud volcano floods Java, August 2006

- Mud volcano work suspended, 25 Feb 2007, Al Jazeera English

- Possible mud volcano on Mars (BBC News)

- Of Mud Pots and the End of the San Andreas Fault (Seismo Blog)

- Mud Volcanoes at West Nile Delta Video by GEOMAR I Helmholtz-Centre for Ocean Research Kiel

- El Totumo volcano near Cartagena, Colombia on YouTube

- World's Only Moving Mud Puddle on YouTube showing the progress over time of the Niland Geyser