Saint-Sylvestre coup d'état

| Saint-Sylvestre coup d'état | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 8 dead | |||||||

|

|---|

|

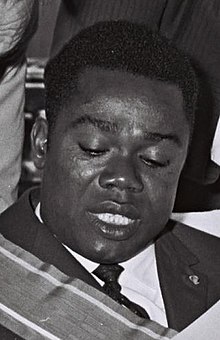

The Saint-Sylvestre coup d'état[a] was a coup d'état staged by Jean-Bédel Bokassa, commander-in-chief of the Central African Republic (CAR) army, and his officers against the government of President David Dacko on 31 December 1965 and 1 January 1966. Dacko, Bokassa's cousin, took over the country in 1960, and Bokassa, an officer in the French army, joined the CAR army in 1962. By 1965, the country was in turmoil—plagued by corruption and slow economic growth, while its borders were breached by rebels from neighboring countries. Dacko obtained financial aid from the People's Republic of China, but despite this support, the country's problems persisted. Bokassa made plans to take over the government; Dacko was made aware of this, and attempted to counter by forming the gendarmerie headed by Jean Izamo, who quickly became Dacko's closest adviser.

With the aid of Captain Alexandre Banza, Bokassa started the coup New Year's Eve night in 1965. First, Bokassa and his men captured Izamo, locking him in a cellar at Camp de Roux. Bokassa's men then occupied the capital, Bangui, and overpowered the gendarmerie and other resistance. After midnight, Dacko headed back to the capital, where he was promptly arrested, forced to resign from office and then imprisoned at Camp Kassaï. According to official reports, eight people were killed during the takeover. By the end of January 1966, Izamo was tortured to death, but Dacko's life was spared because of a request from the French government, which Bokassa was trying to satisfy. Bokassa justified the coup by claiming he had to save the country from falling under the influence of communism, and cut off diplomatic relations with China. In the early days of his government, Bokassa dissolved the National Assembly, abolished the Constitution and issued a number of decrees, banning begging, female circumcision, and polygamy, among other things. Bokassa initially struggled to obtain international recognition for the new government. However, after a successful meeting with the president of Chad, Bokassa obtained recognition of the regime from other African nations, and eventually from France, the former colonial power.

Bokassa's right-hand man Banza attempted his own coup in April 1969, but one of his co-conspirators informed the president of the plan. Banza was put in front of a military tribunal and sentenced to death by firing squad. Dacko, who remained in isolation at Camp de Roux, sent a letter to the Chinese ambassador in Brazzaville in June 1969, which Bokassa intercepted. Bokassa charged Dacko with threatening state security and transferred him to the infamous Ngaragba Prison, where many prisoners taken captive during the coup were still being held. A local judge convinced Bokassa that there was a lack of evidence to convict Dacko, who was instead placed under house arrest. In September 1976, Dacko was named personal adviser to the president; the French government later convinced him to take part in a coup to overthrow Bokassa, who was under heavy criticism for his ruthless dictatorial rule. This coup was carried out on 20 and 21 September 1979, when Dacko became president again, only to be overthrown in another coup two years later.

Background

[edit]

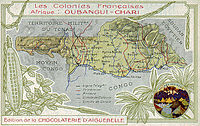

In 1958, after the French Fourth Republic began to consider granting independence to most of its African colonies, nationalist leader Barthélemy Boganda met with Prime Minister Charles de Gaulle to discuss terms for the independence of Oubangui-Chari, a French colonial territory which later became the Central African Republic (CAR).[1] De Gaulle accepted his request, and on 1 December 1958, Boganda declared the establishment of the autonomous CAR, with full independence to follow soon.[2] He became the autonomous territory's first Prime Minister. However, he was killed in a plane crash on 29 March 1959, while en route to the capital, Bangui.[3] National elections were held on 5 April, which were handily won by Boganda's party, Movement for the Social Evolution of Black Africa (MESAN).[4]

Dacko, with the backing of the French High Commissioner, the Bangui Chamber of Commerce, and Boganda's widow, offered himself as a candidate to lead the Council of Government. Goumba was hesitant to divide the populace, and after a month in power conceded the presidency to Dacko.[5] Dacko became consumed with administrative work and, though he had initially retained Goumba as Minister of State, dismissed him after several months. In 1960 Goumba founded a new political party, the Democratic Evolution Movement of Central Africa (MEDAC), and claimed it carried the ideals of Boganda and MESAN. Frightened by its rapid growth, Dacko declared his intent to revive MESAN.[6] The Central African Republic received its full independence from France on 13 August 1960.[7] Dacko pushed several measures through the Assembly which invested him as President of the Republic and head of state, and gave the government wide authority to suppress political opposition.[8] By 1962 he had arrested Goumba and declared MESAN the sole party of the state.[9] Goumba was eventually given a moderate sentence and subsequently permitted to move to France to complete his education.[10]

On 1 January 1962, Dacko's cousin, Jean-Bédel Bokassa, left the French Army and joined the military forces of the CAR with the rank of battalion commandant.[11] Dacko appointed him Chief of Staff of the Central African Army on 1 December 1964.[12]

Bokassa sought recognition for his status as the army's leader; he frequently appeared in public wearing all his military decorations, and in ceremonies often tried to sit next to President Dacko to hint at his importance in the government. Bokassa constantly involved himself in heated arguments with Jean-Paul Douate, the government's chief of protocol, who admonished him for not following the correct order of seating at presidential tables. At first, Dacko found his cousin's antics for power and recognition amusing.[13] Despite the recent rash of African military coups, Dacko publicly dismissed the possibility that Bokassa would someday try to take control of the country. At a state dinner, he said, "Colonel Bokassa only wants to collect medals and he is too stupid to pull off a coup d'état".[14] Other members of Dacko's cabinet saw Bokassa as a major threat to the regime. Jean-Arthur Bandio, the minister of interior, recommended that Bokassa be brought into the cabinet, which he hoped would both satisfy the colonel's desire for recognition and break his connections with the army. To prevent the possibility of a military coup, Dacko created the gendarmerie, an armed police force of 500, headed by Jean Izamo, and a 120-member presidential security guard, led by Prosper Mounoumbaye.[13]

Origins

[edit]Dacko's government faced a number of problems during 1964 and 1965: the economy experienced stagnation, the bureaucracy started to fall apart, and the country's boundaries were constantly breached by Lumumbists from the south and Sudanese militants from the east. Under pressure from radicals in MESAN and in an attempt to cultivate alternative sources of support and display his independence in foreign policy, Dacko established diplomatic relations with the People's Republic of China (PRC) in September 1964. A delegation led by Meng Yieng and agents of the Chinese government toured the country, showing Communist propaganda films. Soon after, the PRC gave the CAR an interest-free loan of one billion CFA francs; however, the aid failed to prevent the prospect of a financial collapse for the country.[15][b] Another problem which plagued the government was widespread corruption.[17] Bokassa felt that he needed to take over the CAR government to remove the influence of Communism and solve all the country's problems. According to Samuel Decalo, a scholar on African government, Bokassa's personal ambitions likely played the most important role in his decision to launch a coup against the government.[18]

Dacko sent Bokassa to Paris as part of a delegation for the Bastille Day celebrations in July 1965. After attending a 23 July ceremony to mark the closing of a military officer training school he had attended decades earlier, Bokassa planned to return to the CAR. However, Dacko had forbidden his return, and Bokassa spent the next few months trying to obtain the support of friends in the French and Central African armed forces for his return. Dacko eventually yielded to pressure and allowed Bokassa back in October.[15][c]

Tensions between Dacko and Bokassa increased. In December, Dacko approved a budget increase for Izamo's gendarmerie, but rejected the budget proposal for Bokassa's army.[20] The budget debate was fractious, and led to a rupture in relations between Izamo and Bokassa.[21] At this point, Bokassa told friends he was annoyed by Dacko's treatment and was "going for a coup d'état".[14] Dacko planned to replace Bokassa with Izamo as his personal military adviser, and wanted to promote army officers loyal to the government, while demoting Bokassa and his close associates. He hinted at his intentions to elders of the Bobangui village, who informed Bokassa of the plan in turn. Bokassa realized he had to act against Dacko quickly, and worried that his 500-man army would be no match for the gendarmerie and the presidential guard. He was also concerned the French would intervene to aid Dacko, as had occurred after the 23 February 1964 coup d'état in Gabon against President Léon M'ba. After receiving word of the coup from the country's vice president, officials in Paris sent paratroopers to Gabon in a matter of hours and M'ba was quickly restored to power.[20] Meanwhile, Izamo made plans to kill Bokassa and overthrow Dacko.[12]

Bokassa found substantive support from his co-conspirator, Captain Alexandre Banza, who was commander of the Camp Kassaï military base in northeast Bangui, and, like Bokassa, had served in the French army in posts around the world. Banza was an intelligent, ambitious and capable man who played a major role in planning the coup.[20] By late December, rumours of coup plots were circulating among officials in the capital.[22] Dacko's personal advisers alerted him that Bokassa "showed signs of mental instability" and needed to be arrested before he sought to bring down the government,[20] but Dacko did not act upon such advice.[22]

Coup d'état on 31 December and 1 January

[edit]

Early in the evening of 31 December 1965, Dacko left the Palais de la Renaissance to visit one of his ministers' plantations southwest of the capital.[20] Izamo phoned Bokassa to invite him to a New Year's Eve cocktail party. Bokassa had been warned that this was a trap to arrest him, and instead requested that Izamo first go to Camp de Roux to sign some papers that needed to be reviewed before the year ended.[23] Izamo reluctantly agreed and traveled in his wife's car to the camp,[24] arriving at about 19:00.[23] Upon arrival, he was confronted by Banza and Bokassa, who informed him of the coup in progress. When asked if he would support the coup, Izamo said no, leading Bokassa and Banza to overpower him and hold him in a cellar. At 22:30, Captain Banza gave orders to his officers to begin the coup: one of his captains was to subdue the security guard in the presidential palace, while the other was to take control of Radio-Bangui to prevent communication between Dacko and his followers.[24]

Shortly after midnight on 1 January 1966, Bokassa and Banza organized their troops and told them of their plan to take over the government. Bokassa claimed that Dacko had resigned from the presidency and given the position to his close advisor Izamo, then told the soldiers that the gendarmerie would take over the CAR army, which had to act now to keep its position. He then asked the soldiers if they would support his course of action; the men who refused were locked up. At 00:30, Bokassa and his supporters left Camp de Roux to take over the capital. They encountered little resistance and were able to take Bangui.[24] A nightguard was shot and killed at the radio station after attempting to hold off soldiers with a bow and arrows.[25] Troops also secured the residences of the government ministers, pillaged them, and took the ministers to a military camp.[23] Bokassa and Banza then rushed to the Palais de la Renaissance, where they tried to arrest Dacko, who was nowhere to be found. Bokassa began to panic, as he believed the president had been warned of the coup in advance, and immediately ordered his soldiers to search for Dacko in the countryside until he was found.[24] To forestall a potential intervention by French troops stationed in Fort-Lamy, Chad, the putschists blocked the runway at Bangui Airport with trucks and barrels. A roadblock was also erected in the capital, and a French national was killed while trying to pass through it.[16]

Dacko was not aware of the events taking place in the capital. After leaving his minister's plantation near midnight, he headed to Simon Samba's house to ask the Aka Pygmy leader to conduct a year-end ritual. After an hour at Samba's house, he was informed of the coup in Bangui. According to Titley, Dacko then left for the capital, in hopes of stopping the coup with the help of loyal members of the gendarmerie and French paratroopers.[26] Others like Thomas E. O'Toole, professor of sociology and anthropology at St. Cloud State University, believed that Dacko was not trying to mount a resistance, instead he was planning on resigning and handing power over to Izamo.[27][d] According to Pierre Kalck, Dacko was attempting to flee to his native district.[23] In any case, Dacko was arrested by soldiers patrolling Pétévo Junction, on the western border of the capital. He was taken back to the presidential palace, where Bokassa hugged the president and told him, "I tried to warn you—but now it's too late". President Dacko was taken to Ngaragba Prison in east Bangui at around 02:00. In a move that he thought would boost his popularity in the country, Bokassa ordered prison director Otto Sacher to release all prisoners in the jail. Bokassa then took Dacko to Camp Kassaï at 03:20, where the president was forced to resign from office. Later, Bokassa's officers announced on Radio-Bangui that the Dacko government had been toppled and Bokassa had taken over control.[26] In the morning, Bokassa addressed the public via Radio-Bangui (in French):

Central Africans! Central Africans! This is Colonel Bokassa speaking to you. Since 3:00 am this morning, your army has taken control of the government. The Dacko government has resigned. The hour of justice is at hand. The bourgeoisie is abolished. A new era of equality among all has begun. Central Africans, wherever you may be, be assured that the army will defend you and your property ... Long live the Central African Republic![26]

Aftermath

[edit]Officially, eight people died in fighting during the coup, including former Minister of Foreign Affairs Maurice Dejean.[23] Afterwards, Bokassa's officers went around the country, arresting Dacko's political allies and close friends, including Simon Samba, Jean-Paul Douate and 64 presidential security guards, who were all taken to Ngaragba Prison.[29] Prosper Mounoumbaye, the director of the presidential security, fled to the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Weeks later, he was detained by the Congolese authorities and handed over to Bokassa on 23 January 1966. At Camp Kassaï, he was beaten and tortured to death, in full view of Bokassa, Banza and Dacko. Jean Izamo met a similar fate: he was transferred to Ngaragba Prison on 10 January, but was tortured to death by the month's end. President Dacko's life was spared, as Bokassa wanted international recognition for his government and France had threatened to cut off aid to the CAR if Dacko was killed. Bokassa had Dacko detained in a small room at Camp Kassaï, where he was cut off from communication with the outside world and placed on a highly restrictive diet. On 1 February, he was taken to Camp de Roux, where he remained in isolation.[25]

In the meantime, Bokassa engaged in self-promotion before the media, showing his countrymen his French army medals, and displaying his strength, fearlessness and masculinity.[30] In an attempt to preserve calm, he ordered all civil servants to return to their work under threat of dismissal.[31] He formed a new government called the Revolutionary Council, invalidated the constitution and dissolved the National Assembly, calling it "a lifeless organ no longer representing the people".[30] In his address to the nation, Bokassa claimed that the government would hold elections in the future, a new assembly would be formed, and a new constitution would be written. He also told his countrymen that he would give up his power after the communist threat had been eliminated, the economy stabilized, and corruption rooted out.[32] President Bokassa allowed MESAN to continue functioning, but barred all other political organizations from the country. In the coming months, Bokassa imposed a number of new rules and regulations: men and women between the ages of 18 and 55 had to provide proof that they had jobs, or else they would be fined or imprisoned; begging was banned; tom-tom playing was allowed during the nights and weekends; and a "morality brigade" was formed in the capital to monitor bars and dance halls. Polygamy, dowries and female circumcision were all abolished. Bokassa also opened a public transport system in Bangui and subsidized the creation of two national orchestras.[33]

Despite the positive changes in the country, Bokassa had difficulty obtaining international recognition for his new government.[25] He tried to justify the coup by explaining that Izamo and communist Chinese agents were trying to take over the government and that he had to intervene to save the CAR from the influence of communism. He alleged that Chinese agents in the countryside had been training and arming locals to start a revolution, and on 6 January 1966, he expelled Chinese representatives from the country and severed diplomatic relations with China.[34] Bokassa also stated that the coup was necessary in order to prevent further corruption in the government.[35]

Bokassa first secured diplomatic recognition from President François Tombalbaye of neighboring Chad, whom he met in Bouca, Ouham. After Bokassa reciprocated by meeting Tombalbaye on 2 April 1966 along the southern border of Chad at Fort Archambault, the two decided to help one another if either was in danger of losing power. Soon after, other African countries began to diplomatically recognize the new government. At first, the French government was reluctant to support the Bokassa regime.[35] The French Foreign Ministry drafted a statement of condemnation, but its release was demurred by other officials who considered Bokassa to be a Francophile. The French government eventually told its embassy officials in Bangui to work with Bokassa but refrain from treating him as a head of state.[16] Banza went to Paris to meet with French officials to convince them that the coup was necessary to save the country from turmoil. Bokassa met with Prime Minister Georges Pompidou on 7 July 1966, but the French remained noncommittal in offering their support. After Bokassa threatened to withdraw from the franc monetary zone, President Charles de Gaulle decided to make an official visit to the CAR on 17 November 1966. To the Bokassa regime, this visit meant that the French had finally accepted the new changes in the country.[35]

Banza and Dacko

[edit]Alexandre Banza, who stood by Bokassa throughout the planning and execution of the coup, served as minister of finance and minister of state in the new government. Banza was successful in his efforts at building the government's reputation abroad; many believed that he would no longer accept serving as Bokassa's right-hand man. In 1967, Banza and Bokassa had a major argument regarding the country's budget, as Banza adamantly opposed Bokassa's extravagance at government events. Bokassa moved to Camp de Roux, where he felt he could safely run the government without having to worry about Banza's thirst for power.[36] On 13 April 1968, Bokassa demoted Banza from minister of finance to minister of health, but let him remain in his position as minister of state. The following year, Banza made a number of remarks highly critical of Bokassa and his management of the economy. At this point, Bokassa realized that his minister would soon attempt to take over power in the country, so he removed him as his minister of state.[37]

Banza revealed his intention to start a coup to Lieutenant Jean-Claude Mandaba, the commanding officer of Camp Kassaï, who promptly informed Bokassa. When he entered Camp Kassaï on 9 April 1969 (the coup was planned for that evening), Banza was ambushed, thrown into the trunk of a Mercedes and taken directly to Bokassa by Mandaba and his soldiers.[37] At his house in Berengo, Bokassa nearly beat Banza to death before Mandaba suggested that Banza be put on trial for appearance's sake. On 12 April, Banza presented his case before a military tribunal at Camp de Roux, where he admitted to his plan, but stated that he had not planned to kill Bokassa. Nevertheless, he was sentenced to death by firing squad, taken to an open field behind Camp Kassaï, executed and buried in an unmarked grave.[38]

Ex-President Dacko remained in isolation at Camp de Roux, where the French government, which expressed concern for his well-being, sent a military attaché to visit him. Dacko told the attaché that he had not been given anything to read for more than two years; the attaché negotiated with the prison head to get Dacko some books. However, Dacko's living conditions failed to improve, and in June 1969, Dacko sent a letter to the Chinese ambassador in Brazzaville, asking that he offer financial support to his family. The message was intercepted and handed over to Bokassa,[39] who thought the letter was ample reason for him to get rid of Dacko. Dacko was charged with threatening state security and transferred to Ngaragba Prison. However, Bokassa dropped the charges on 14 July, after Judge Albert Kouda convinced him that there was insufficient evidence to get a conviction. Dacko stayed at the Palais de la Renaissance until his health improved, after which he was sent to live in Mokinda, Lobaye under house arrest.[36]

Dacko remained under house arrest until he was named private adviser to President Bokassa on 17 September 1976. Bokassa dissolved the government and formed the Central African Empire, which led to increasing international criticism in the late 1970s. Dacko managed to leave for Paris, where the French convinced him to cooperate in a coup to remove Bokassa from power and restore him to the presidency.[40] Dacko was installed as president on 21 September 1979, but was once again removed from power by his army chief of staff, André Kolingba, in a bloodless coup d'état on 1 September 1981.[41] Bokassa was granted asylum in Côte d'Ivoire and was sentenced to death in absentia by the Criminal Court of Bangui in December 1980. An international warrant for his arrest was issued, but the Ivorian government refused to extradite him.[42] Upon returning to the CAR on his own volition in October 1986, he was arrested. After a 90-day trial he was sentenced to death on 12 June 1987. Kolingba commuted his sentence to life imprisonment in February 1988, and then commuted it again to 20 years in prison. Kolingba later pardoned Bokassa in September 1993 and the latter was released from prison under police supervision.[43]

Notes

[edit]- ^ 31 December is the feast day of Saint Sylvester, and in French, New Year's Eve is referred to as Saint-Sylvestre. Although the coup d'état began on New Year's Eve and finished in the early hours of New Year's Day, scholarly sources like Kalck 2005 and Titley 1997 have referred to the coup as the "Saint-Sylvestre coup d'état" or "Coup d'état of Saint-Sylvestre".

- ^ While the French government was initially shocked by the turn towards China, Dacko assured a French official that the move was meant to satisfy MESAN youth and reduce the CAR's appearance of dependency on French aid. The official concluded that "the new developments in Central African politics did not seem to reduce the country's attachment to France nor to suggest some disaffection."[16]

- ^ Bokassa claimed that Dacko finally gave up after French President Charles de Gaulle personally intervened, telling Dacko that "Bokassa must be immediately returned to his post. I cannot tolerate the mistreatment of my companion-in-arms".[19]

- ^ O'Toole criticized Titley's account of the coup for relying too much on Bokassa's memoir and interviews with Dacko and accused him of presenting "a much more flattering picture of Dacko than what emerges from other, less self-serving, sources."[28]

References

[edit]- ^ Kalck 2005, pp. 83–84.

- ^ Kalck 2005, p. 27.

- ^ "African Leader Found Dead in Crashed Plane", The New York Times, p. 10, 1 April 1959.

- ^ Kalck 1971, pp. 106–107.

- ^ Kalck 1971, p. 107.

- ^ Kalck 1971, pp. 108–109.

- ^ Kalck 1971, p. 119.

- ^ Kalck 1971, pp. 120–122.

- ^ Titley 1997, p. 20.

- ^ Kalck 2005, p. 91.

- ^ Titley 1997, p. 23.

- ^ a b Marcum & Brown 2016, p. 273.

- ^ a b Titley 1997, p. 24.

- ^ a b Péan 1977, p. 15.

- ^ a b Titley 1997, p. 25.

- ^ a b c Correau, Laurent (26 February 2016). "Archives Foccart: la France et le coup d'Etat de Bokassa". RFI. Radio France Internationale. Retrieved 31 December 2021.

- ^ Lee 1969, p. 100.

- ^ Decalo 1973, p. 111.

- ^ Bokassa 1985, p. 24.

- ^ a b c d e Titley 1997, p. 26.

- ^ Kalck 1971, pp. 152–153.

- ^ a b Kalck 2005, p. 557.

- ^ a b c d e Kalck 1971, p. 153.

- ^ a b c d Titley 1997, p. 27.

- ^ a b c Titley 1997, p. 29.

- ^ a b c Titley 1997, p. 28.

- ^ O'Toole 1998, pp. 155–156.

- ^ O'Toole 1998, p. 155.

- ^ Titley 1997, pp. 28–29.

- ^ a b Titley 1997, p. 33.

- ^ "Peace Sought in Bangui". The New York Times. United Press International. 3 January 1966. p. 10.

- ^ Titley 1997, p. 34.

- ^ Titley 1997, p. 35.

- ^ Titley 1997, pp. 29–30.

- ^ a b c Titley 1997, p. 30.

- ^ a b Titley 1997, p. 41.

- ^ a b Titley 1997, p. 42.

- ^ Titley 1997, p. 43.

- ^ Titley 1997, p. 40.

- ^ Titley 1997, p. 127.

- ^ Titley 1997, p. 160.

- ^ Kalck 2005, pp. 29–30.

- ^ Kalck 2005, p. 30.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bokassa, Jean-Bédel (1985), Ma vérité (in French), Paris: Carrére Lefon

- Decalo, Samuel (March 1973), "Military Coups and Military Regimes in Africa", The Journal of Modern African Studies, 11 (1): 105–127, doi:10.1017/S0022278X00008107, S2CID 154338499

- Kalck, Pierre (1971), Central African Republic: A Failure in De-Colonisation, translated by Barbara Thomson, London: Pall Mall Press, ISBN 0-269-02801-3

- Kalck, Pierre (2005), Historical Dictionary of the Central African Republic (3rd English ed.), Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press, ISBN 0-8108-4913-5

- Lee, J. M. (1969), African Armies and Civil Order, New York: Praeger, OCLC 23680

- Marcum, Anthony S.; Brown, Jonathan N. (March 2016). "Overthrowing the "Loyalty Norm": The Prevalence and Success of Coups in Small-coalition Systems, 1950 to 1999". The Journal of Conflict Resolution. 60 (2): 256–282. doi:10.1177/0022002714540469. JSTOR 24755911. S2CID 155388146.

- O'Toole, Thomas E. (September 1998), "Review: Brian Titley. Dark Age: The Political Odyssey of Emperor Bokassa", African Studies Review, 41 (2), African Studies Association: 155–157, doi:10.2307/524838, JSTOR 524838, S2CID 149558813

- Péan, Pierre (1977), Bokassa Ier (in French), Paris: Editions Alain Moreau, OCLC 4488325

- Titley, Brian (1997), Dark Age: The Political Odyssey of Emperor Bokassa, Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, ISBN 0-7735-1602-6