Pascal Sébah

Pascal Sébah | |

|---|---|

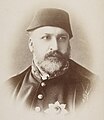

Possible self-portrait of Pascal Sebah in front of the Sultan Ahmed III Fountain, c. 1867. | |

| Born | 1823 |

| Died | June 25, 1886 Istanbul, Ottoman Empire |

| Children | Jean Pascal Sébah |

Pascal Sébah (1823 – June 25, 1886) was an Ottoman photographer in Istanbul and Cairo. Best known for his prolific photography of Anatolia, Egypt, and Greece, Sébah established the studio that would later become Sébah & Joaillier.

Life and work

[edit]

Pascal Sébah was born in Istanbul, then the capital of the Ottoman Empire, to a Syrian father and an Armenian mother.[1]

He initially worked in collaboration with the French photographer, Henri Bechard.[2] After receiving medals at the International Exhibition in Paris, he decided to open his own studio in Constantinople in 1857.[3] Sébah's studio was known as ''El Chark (meaning "The Orient"), situated at 439 Grande Rue de Pera in the center of the city and close to the embassies and hotels where tourists met.[4]

Sébah primarily produced photographs for the tourist trade. By the second half of the 19th century, tourist travel to Egypt had created a strong demand for photographs as souvenirs. Sébah was among a group of early photographers in Constantinople and Cairo to capitalise on this demand. These pioneering photographers included Félix Bonfils (1831-1885); Gustave Le Gray (1820-1884), brothers Henri and Emile Bechard; the British-Italian brothers Antonio Beato (c. 1832–1906) and Felice Beato and the Greek Zangaki brothers.[5] By 1873 Sébah was successful enough to open a second studio in Cairo. The same year, he exhibited at the Ottoman pavilion of the Universal Exhibition in Vienna, Austria.[2]

He established a valuable working relationship with Turkish painter and archeologist Osman Hamdi Bey, taking photographs as part of the artist's preparation, and in which he experimented with light and shade.[6] In turn, Hamdi Bey selected Sébah to illustrate his text on the popular costumes worn by Turkish and other ethnic groups, entitled Les Costumes Populaires de la Turquie en 1873: ouvrage publié sous le patronage de la Commission impériale ottomane pour l'Exposition universelle de Vienne and published in 1873.[7]

Following his death on 25 June 1886, the studio continued in business. It was managed by his brother, Cosmi, and in 1888 Polycarpe Joiallier became a partner. At this time, the company was renamed Sebah & Joaillier[6] Pascal's son, Jean Pascal Sébah, also joined in 1888 and went on to run the studio with other photographers. The firm developed a reputation as the leading representative of Orientalist photography and in 1889 was appointed the Photographers by Appointment to the Prussian Court.[6] Sébah's studio continued operations, in one form or another, until 1952 at the same address and then moved until its closure in 1973.[1]

Sébah, a Syrian Catholic, was buried in the Feriköy Latin Catholic Cemetery in Istanbul. His son, Jean Pascal Sébah, is also buried there.

Gallery of photographs by Sébah

[edit]-

Portrait of Sultan Abdul Aziz by Pascal Sébah

-

Damascus fashion, illustration from the book Popular Costumes in Turkey, 1873

-

Turkish Women of Constantinople, illustration from the book Popular Costumes in Turkey, 1873

-

Syrian fashion, illustration from the book Popular Costumes in Turkey, 1873

-

Bedouins from Aleppo, illustration from the book Popular Costumes in Turkey, 1873

-

Fashion (l-r): Zahle, Lebanon, and (Zgharta); illustration from the book Popular Costumes in Turkey, 1873

-

Christian couple from Shkodra, illustration from the book Popular Costumes in Turkey, 1873

-

Dendra: "Temple of Hathor"

-

Abydoss Seti I Offering Incense to Osiris

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Philip Carabott, Yannis Hamilakis and Eleni Papargyriou (eds), Camera Graeca: Photographs, Narratives, Materialities, Routledge, 2016, p. 114

- ^ a b Photography in Ottoman Istanbul by Margaret Kurkoski, 2013-2015 Curatorial Fellow, Smith College Museum of Art

- ^ Hannavy, J., Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography, Routledge, 2013, p. 1032

- ^ J. Paul Getty Museum; Note that the source confuses father and son. Confusion between Pascal Sébah (father) and son Jean Pascal Sébah (son) is not uncommon. Users should be very careful when using images from Wiki Commons as this source also confuses the two photographers and the World Cat Identities exhibits similar problems with identities. Other sources are more careful, see for instance, Philip Carabott, Yannis Hamilakis and Eleni Papargyriou (eds), Camera Graeca: Photographs, Narratives, Materialities, Routledge, 2016, p. 114

- ^ Jacobson, K., Odalisques and Arabesques: Orientalist Photography, 1839-1925, London, Bernard Quaritch, 2007, p. 277.

- ^ a b c Hannavy, J., Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography, Routledge, 2013, p. 1036

- ^ Osman Hamdi Bey; Marie de Launay; J Pascal Sébah, Les Costumes Populaires de la Turquie en 1873: ouvrage publié sous le patronage de la Commission impériale ottomane pour l'Exposition universelle de Vienne, Turkey, Commission impériale ottomane pour l'Exposition universelle de Vienne, 1873

General references

[edit]- Fabrizio Casaretto, Sébah & Joaillier photos. www.sebahjoaillier.com

- Engin Özendes, From Sébah & Joaillier to Foto Sabah. Orientalism in Photography, Istanbul, YKY, 1999.

- Michelle L. Woodward, "Between Orientalist Clichés and Images of Modernization: Photographic Practice in the Late Ottoman Era," History of Photography, winter 2003, Vol. 27, No. 4. doi:10.1080/03087298.2003.10441271

External links

[edit]- Les Costumes Popularies de la Turquie en 1873 by Osman Bey Hamdi with illustrations by Pascal Sébah

- Vintage Rag Trader - Vintage Photographs by Pascal Sebah

- Pascal Sebah blog on Sebah's biography

- Pascal Sébah blog on Sebah's biography

- (in French) Bibliothèque numérique de l'INHA - Fonds photographique Pascal Sébah de l'ENSBA