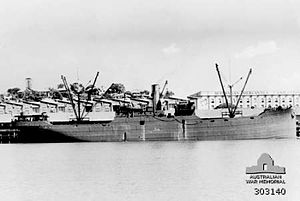

SS Coast Trader

SS Coast Farmer, the SS Coast Trader sister ship

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name |

|

| Owner |

|

| Port of registry | New York, New York( |

| Builder | Submarine Boat Corporation, Newark |

| Yard number | 108 |

| Laid down | 30 September 1919 |

| Launched | January 1920 |

| Completed | May 1920 |

| Identification | US Official Number 219588 |

| Fate | Sunk by I-26 in 1942 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | EFC Design 1023, postwar commercial completion |

| Tonnage | |

| Displacement | 7,615 tons |

| Length |

|

| Beam | 46 ft (14.0 m) |

| Draft | 23 ft (7.0 m) |

| Depth | 28 ft 6 in (8.7 m) molded |

| Installed power | 2 Babcock & Wilcox water tube boilers, 1,500 hp (1,100 kW) |

| Propulsion | Westinghouse steam turbine, one quadruple-blade propeller |

| Speed | 10.5 knots (19.4 km/h; 12.1 mph) |

| Crew | 57 |

SS Coast Trader was built as the cargo ship SS Holyoke Bridge in 1920 by the Submarine Boat Company in Newark, New Jersey. The Coast Trader was torpedoed and sank 35 nautical miles (65 km; 40 mi) southwest of Cape Flattery, off the Strait of Juan de Fuca in U.S. state of Washington by the Japanese submarine I-26. Survivors were rescued by schooner Virginia I and HMCS Edmundston. She rests on the ocean floor at (48°19′N 125°40′W / 48.317°N 125.667°W).[1]

Construction

[edit]The SS Holyoke Bridge was built on the design 1023 ship plan. The 1023 ship plan was approved for mass production by the United States Shipping Board's (USSB) Emergency Fleet Corporation (EFC) for World War I support. Holyoke Bridge is one of the 118 identical ships built to offset the losses from the war. The Holyoke Bridge was original planned as the SS Yashi, but was renamed before the ship was launched. The ships were powered by Westinghouse steam engines and two boilers. The ship was: 3,658 GRT, 2,214 NRT, length of 324.0 ft (98.8 m), a beam of 46.2 ft (14.1 m), a draft of 25 m (82 ft) and top speed of 10.5 knots (19.4 km/h; 12.1 mph). The ship's hull yard number was 108, ship ID 842 and she was delivered for service in May 1920.[2][3][4]

History

[edit]While built to support World War I, she was complete in May 1920, too late to support the war effort. She did help in the support of the post war supply movement. SS Holyoke Bridge was owned and operated by the United States Shipping Board from 1920 until she was sold in 1926. The Holyoke Bridge was sold to Swayne & Hoyt Lines, that operated the Gulf Pacific Mail Line Ltd., of San Francisco, California. Swayne & Hoyt renamed her Point Reyes in 1926. Point Reyes was sold to the Coastwise Line Steamship Company, associated Pacific Far East Lines, of San Francisco and renamed the Coast Trader in 1937. Coast Trader homeport was Portland, Oregon. In 1941 the Coast Trader began operation as a contract cargo ship for the U.S. Army for World War II by the War Shipping Administration on December 22, 1941.[5]

World War II

[edit]After the Attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the Imperial Japanese Navy sent five submarines — I-17, I-19, I-23, I-25, and I-26 — to attack ships off West Coast of the United States. In early June 1942, I-26 took part in the opening stages of the Aleutian Islands campaign. I-26 then sailed off Washington state.[6]

Sinking

[edit]On June 7, 1942 the Coast Trader departed Port Angeles, Washington for San Francisco with a cargo of blank newsprint. The Coast Trader had just passed through the Strait of Juan de Fuca at 2:10 pm, when she was found and torpedoed by I-26. The Coast Trader sank in just 40 minutes. Coast Trader had lookouts watching for Japanese submarines, but I-26, had been following the ship for 4 miles (6.4 km), since Neah Bay, Washington, at periscope depth. The torpedo put a six-foot (1.8 m) hole in the starboard side of the ship just below cargo hatch #4 in the stern, allowing water to rush in. The torpedo explosion tossed cargo hatch #4's cover, as well as part the 2,000 pounds (910 kg) of rolls of newsprint stowed in hold #4, into the air. The engine room flooded and the engines stopped. Captain Lyle G. Havens gave crew the order to abandon ship. The crew disembarked the sinking vessel in a lifeboat and two life rafts. The radio was damaged and the radio operator did not get out an SOS. All the crew made it safely into the lifeboat and rafts, but one crew member died of exposure. The lifeboat tried to row to land with the rafts in tow, but in the night a storm came in with 60-knot (110 km/h; 69 mph) winds and heavy seas. The raft's rope line came off in the night. In the morning the lifeboat raised her sail and continued, not able to find the rafts. Two days later at 4:00 pm, the lifeboat crew was rescued after being spotted by the Virginia I a fishing vessel from San Francisco. Virginia I called in an SOS, and a United States Coast Guard aircraft found the rafts from a flare they put up. The aircraft sent HMCS Edmundston, a Canadian corvette, that found the two rafts on June 9, 1942. The raft crews were cold and wet after spending 40 hours on the rafts. The Coast Trader had a crew of 56: nine officers, 28 seamen and 19 United States Army armed guards that manned the deck guns. The crewmen that were suffering from injuries and exposure were hospitalized at Port Angeles. The Coast Trader was the first American vessel the Imperial Japanese Navy sank off the coast of Washington State during World War II.

The United States Navy did not, a first, want to acknowledge that Japanese submarines were active off the US West Coast due to the U-boat's Second Happy Time. Thus, they at first attributed the sinking of Coast Trader to an internal explosion.[7][8]

The commander of I-26, Minoru Yokota, reported torpedoing a merchant vessel on the date and at the location where the Coast Trader sank, when he returned to Yokosuka, Japan on July 7, 1942. He also reported shelling Estevan Point lighthouse on June 20, 1942 and sinking the SS Cynthia Olson on December 7, 1941. I-26 was sunk by USS Richard M. Rowell, a destroyer escort, during the Battle of Leyte Gulf on October 25, 1944.[9]

Wreck

[edit]SS Coast Trader was later found resting on the sea bottom at a depth of 486 feet (148 m). In 2016 the EV Nautilus, an American research vessel owned by the Ocean Exploration Trust, explored the wreck of the Coast Trader. EV Nautilus' remotely operated underwater vehicles Hercules and Argus found the Coast Trader resting upright on the sea floor. The data is being studied by National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration maritime archaeologist Dr. James P. Delgado. It is believed that the Coast Trader may still have on board 8,088 barrels of fuel oil, which is a concern. It was found that the Coast Trader had become an artificial reef, as different types of marine life have made her home. The Inner Space Center, in Narragansett, Rhode Island continued to study the drive's data.[10]

See also

[edit]- SS Mopang, sister ship

- SS Admiral Halstead, sister ship

- SS Coast Farmer, sister ship

References

[edit]- ^ "Imperial Submarines". Combinedfleet.com. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- ^ Mercogliano, Salvatore R. (October 2016). "The Shipping Act of 1916 and Emergency Fleet Corporation: America Builds, Requisitions, and Seizes a Merchant Fleet Second to None" (PDF). The Northern Mariner/Le Marin du Nord. XXVI (4): 407–424. doi:10.25071/2561-5467.230. S2CID 246796503.

- ^ Fifty Second Annual List of Merchant Vessels of the United States, Year ended June 30, 1920. Washington, D.C.: Department of Commerce, Bureau of Navigation. 1920. p. 70. hdl:2027/nyp.33433023733920. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- ^ Submarine Boat Corporation (November 15, 1923). "Explaining the Names of Transmarine Steamers". Speed Up. Vol. 6, no. 11. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- ^ shipbuildinghistory, Submarine Boat Company, Newark NJ

- ^ Morison, Samuel Eliot, History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Volume IV: Coral Sea, Midway, and Submarine Actions, May 1942–August 1942, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1988, p. 173.

- ^ Webber, Bert, Retaliation: Japanese Attacks and Allied Countermeasures on the Pacific Coast in World War II, Oregon State University Press, 1975, pp. 18-19

- ^ wrecksite Coast Trader

- ^ historylink.org SS Coast Trader

- ^ nautiluslive.org, Rediscovering SS Coast Trader, by Amber Hale