Santiago Ramón y Cajal

Santiago Ramón y Cajal | |

|---|---|

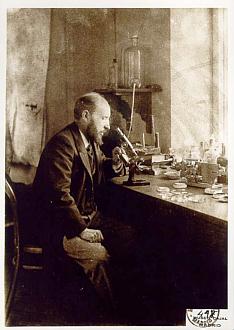

Ramón y Cajal in 1899 | |

| Born | 1 May 1852 |

| Died | 17 October 1934 (aged 82) Madrid, Spain |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Education | University of Zaragoza |

| Known for | Fathering modern neuroscience Discovery of the neuron Cajal body, Cajal–Retzius cell, Interstitial cell of Cajal, Neuron doctrine, Growth cone, Dendritic spine, Long-term potentiation, Mossy fiber, Neurotrophic theory, Axo-axonic synapse, Pioneer axon, Pyramidal cell, Radial glial cell, Retinal ganglion cell, Trisynaptic circuit, Visual map theory |

| Awards | Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine (1906) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Neuroscience Pathology Histology |

| Institutions | University of Valencia Complutense University of Madrid University of Barcelona |

| Signature | |

Santiago Ramón y Cajal (Spanish: [sanˈtjaɣo raˈmon i kaˈxal]; 1 May 1852 – 17 October 1934)[1][2] was a Spanish neuroscientist, pathologist, and histologist specializing in neuroanatomy and the central nervous system. He and Camillo Golgi received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1906.[3] Ramón y Cajal was the first Spaniard to win a scientific Nobel Prize. His original investigations of the microscopic structure of the brain made him a pioneer of modern neuroscience.

Hundreds of his drawings illustrating the arborization (tree-like growth) of brain cells are still in use, since the mid-20th century, for educational and training purposes.[4]

Biography

[edit]Santiago Ramón y Cajal was born on the 1st of May 1852 in the town of Petilla de Aragón, Navarre, Spain.[1] As a child he was transferred many times from one school to another because of behavior that was declared poor, rebellious, and anti-authoritarian. An extreme example of his precociousness and rebelliousness at the age of eleven is his 1863 imprisonment for destroying his neighbor's yard gate with a homemade cannon.[5] He was a keen painter, artist, and gymnast, but his father neither appreciated nor encouraged these abilities, even though these artistic talents would contribute to his success later in life.[2] His father apprenticed him to a shoemaker and barber, to "try and give his son much-needed discipline and stability."[2]

Over the summer of 1868, his father took him to graveyards to find human remains for anatomical study. Early sketches of bones moved him to pursue medical studies.[6]: 207 Ramón y Cajal attended the medical school of the University of Zaragoza, where his father worked as an anatomy teacher. He graduated in 1873, aged 21, and then served as a medical officer in the Spanish Army. He took part in an expedition to Cuba in 1874–1875, where he contracted malaria and tuberculosis.[7] To aid his recovery, Ramón y Cajal spent time in the spa-town Panticosa in the Pyrenees mountain range.[8]

After returning to Spain, he received his doctorate in medicine in Madrid in 1877. Two years later, he became director of the Anatomical Museum at the University of Zaragoza and married Silveria Fañanás García, with whom he would have seven daughters and five sons. Ramón y Cajal worked at the University of Zaragoza until 1883, when he was awarded the position of anatomy professor of the University of Valencia.[7][9] His early work at these two universities focused on the pathology of inflammation, the microbiology of cholera, and the structure of epithelial cells and tissues.[10]

In 1887 Ramón y Cajal moved to Barcelona for a professorship.[7] There he first learned about Golgi's method, a cell staining method which uses potassium dichromate and silver nitrate to (randomly) stain a few neurons a dark black color, while leaving the surrounding cells transparent. This method, which he improved, was central to his work, allowing him to turn his attention to the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord), in which neurons are so densely intertwined that standard microscopic inspection would be nearly impossible. During this period he made extensive detailed drawings of neural material, covering many species and most major regions of the brain.[11]

In 1892, he became professor at Madrid.[7] In 1899 he became director of the Instituto Nacional de Higiene – translated as National Institute of Hygiene, and in 1922 founder of the Laboratorio de Investigaciones Biológicas – translated as Laboratory of Biological Investigations, later renamed to Instituto Cajal, or Cajal Institute.[7]

He died in Madrid on October 17, 1934, at the age of 82,[12] continuing to work even on his deathbed.[7][13]

Political and religious views

[edit]In 1877, the 25-year-old Ramón y Cajal joined a Masonic lodge.[14]: 156 John Brande Trend wrote in 1965 that Ramón y Cajal "was a liberal in politics, an evolutionist in philosophy, an agnostic in religion".[15]

Nonetheless, Ramón y Cajal used the term soul "without any shame".[16] He was said to later have regretted having left organized religion.[14]: 343 Ultimately, he became convinced of a belief in God as a creator, as stated during his first lecture before the Spanish Royal Academy of Sciences.[17][18]

Discoveries and theories

[edit]

Ramón y Cajal made several major contributions to neuroanatomy.[6] He discovered the axonal growth cone, and demonstrated experimentally that the relationship between nerve cells was not continuous, or a single system as per then extant reticular theory, but rather contiguous;[6] there were gaps between neurons. This provided definitive evidence for what Heinrich Waldeyer would name "neuron theory", now widely considered the foundation of modern neuroscience.[6] He is also considered by some to be the first "neuroscientist" since in 1894 he stated to the Royal Society of London: "The ability of neurons to grow in an adult and their power to create new connections can explain learning." This statement is considered to be the origin of the synaptic theory of memory.[19]

He was an advocate of the existence of dendritic spines, although he did not recognize them as the site of contact from presynaptic cells. He was a proponent of polarization of nerve cell function and his student, Rafael Lorente de Nó, would continue this study of input-output systems into cable theory and some of the earliest circuit analysis of neural structures.[20]

By producing depictions of neural structures and their connectivity and providing detailed descriptions of cell types he discovered a new type of cell, which was subsequently named after him, the interstitial cell of Cajal (ICC).[21] This cell is found interleaved among neurons embedded within the smooth muscles lining the gut, serving as the generator and pacemaker of the slow waves of contraction which move material along the gastrointestinal tract, mediating neurotransmission from motor neurons to smooth muscle cells.

In his 1894 Croonian Lecture, Ramón y Cajal suggested (in an extended metaphor) that cortical pyramidal cells may become more elaborate with time, as a tree grows and extends its branches.[22]

He studied some psychological phenomena, such as hypnotic suggestion to alleviate pain, which he used to help his wife during labor. A book he had written on these topics was lost during the Spanish Civil War.[23]

During his studies on the optic chiasma, Cajal developed a visual map-based theory offering an evolutionary explanation for the decussation of nerve fibres and the chiasm of the optic tract.[24][25]

Distinctions

[edit]

Ramón y Cajal received many prizes, distinctions, and societal memberships during his scientific career, including honorary doctorates in medicine from Cambridge University and Würzburg University and an honorary doctorate in philosophy from Clark University.[7] The most famous distinction he was awarded was the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1906, together with the Italian scientist Camillo Golgi "in recognition of their work on the structure of the nervous system".[7] This caused some controversy because Golgi, a staunch supporter of reticular theory, disagreed with Ramón y Cajal in his view of the neuron doctrine.[26] Before Ramón y Cajal's work, Norwegian scientist Fridtjof Nansen had established the contiguous nature of nerve cells in his study of certain marine life, which Ramón y Cajal failed to cite.[27] Ramón y Cajal was an International Member of both the United States National Academy of Sciences and the American Philosophical Society.[28][29]

In society and culture

[edit]In 1906 Joaquin Sorolla y Bastida painted Cajal's official portrait celebrating his Nobel Prize win.[30]

Cajal posed for a statue that was created by the sculptor Mariano Benlliure and was installed in 1924 in the Paraninfo building at the School of Medicine of the University of Zaragoza.

In 1931 a monument was unveiled in Madrid, Spain. This full-body statue stands 3 meters (around 10 ft) high on a narrow pedestal and was created by Lorenzo Domínguez,[31] a Chilean medical student.

1982 a TV mini series was created in Spain titled Ramón y Cajal: Historia de una voluntad.[32]

In 2003, the first major exhibition of Cajal's scientific drawings opened in Madrid, Spain. The exhibition featured hundreds of restored original drawings, micrographic slides, and personal photographs created by Cajal. The accompanying catalog titled Santiago Ramon y Cajal (1852–2003) Ciencia y Arte[33] features numerous high quality reproductions of Cajal's drawings and photo essays on the restoration process. Exhibition curators and contributing authors to the catalog include: Santiago Ramón y Cajal Junquera, Miguel Ángel Freire Mallo, Paloma Esteban Leal, Pablo García, Virginia G. Marin, Ma Cruz Osuna, Isabel Argerich Fernández, Paloma Calle, Marta C. Lopera, Ricardo Martínez, Pilar Sedano Espín, Eugenia Gimeno Pascual, Sonia Tortajada, and Juan Antonio Sáez Dégano.

In 2005 the asteroid 117413 Ramonycajal was named after him by Juan Lacruz.

In 2007, sculptures of Severo Ochoa and Santiago Ramón y Cajal created by Víctor Ochoa were unveiled at the Spanish National Research Council central headquarters in Madrid, Spain.[34]

Santiago Ramón y Cajal Museum, Ayerbe, Huesca, Spain opened in 2013 and is located in Cajal's childhood home, where he lived with his family for ten years.[35]

In 2014, the National Institutes of Health initiated an ongoing exhibition of original Ramón y Cajal drawings in the John Porter Neuroscience Research Center, located in the NIH central campus in Bethesda, MD, USA. The exhibition concept was spearheaded by NINDS Senior Researcher Jeffery Diamond and NINDS science writer Christopher Thomas and was made possible through close collaboration with the Instituto Cajal, Madrid, Spain.[36] The exhibition also includes contemporary artwork curated by Jeff Diamond, which was created by artists Rebecca Kamen and Dawn Hunter.[37] Inspired by Cajal's original drawings, Kamen's and Hunter's artworks are thematically representative of Cajal's aesthetic and are on permanent display for the public at the John Porter Neuroscience Research Center. Through the award of a 2017–2018 Fulbright España Senior Research Fellowship[38][39] to the Instituto Cajal, Madrid, Spain, Hunter continued to develop her creative project about Cajal by referencing original source material.[40][41]

A selection of Cajal's scientific drawings, personal photos, oil paintings, and pastel drawings were curated into the 14th Istanbul Biennial, Saltwater, that was held in Istanbul, Turkey from September 5 – November 1, 2015.[42]

The exhibition Fisiología de los Sueños. Cajal, Tanguy, Lorca, Dalí... opened on October 5, 2015, and ended on January 16, 2016, at the University of Zaragoza, Zaragoza, Spain. Cajal's work was the centerpiece topic of the exhibition and the show explored the influence of histological drawings on Surrealism.[43]

From January 31 – May 29, 2016, Cajal's work was featured in the inaugural exhibition for the re-opening of University of California's Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive Architecture of Life. The catalog for the exhibition featured Cajal's drawing of the Purkinje Cell on the front cover.[44]

The National Institutes of Health, USA, and the Instituto Cajal, Spain, held collaborative symposiums honoring Cajal on October 28, 2015, and May 24, 2017. The first symposium held at the NIH in 2015 was titled Bridging the Legacy of Santiago Ramón y Cajal, a symposium honoring the father of modern neuroscience. Keynote speaker Dr. Rafael Yuste was honored at a reception held at the Spanish Ambassador's, Ramón Gil-Casares, home. The second symposium titled, New Opportunities for NIH-CSIC Collaboration, was held at the Instituto Cajal in 2017. Dawn Hunter's Cajal Inventory art project was exhibited at the symposium for the general public in the institute's library. The Cajal Inventory consists of forty-five 11” x 14” drawings in which Hunter recreated in fine detail Cajal's scientific drawings from primary source, and surreal portrait drawings of Cajal inspired by his photography.[45]

Every year since 2001, more than two hundred postdoctoral scholarships are awarded by the Spanish Ministry of Science to middle career scholars from different fields of knowledge. They are called "Ayudas a contratos Ramón y Cajal" to honor his memory.[46]

An exhibition called The Beautiful Brain: The Drawings of Santiago Ramón y Cajal travelled through North America, beginning 2017 in the US at the Weisman Art Museum in Minneapolis, Minnesota. The exhibition traveled to the Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada,[47] Grey Art Gallery, New York University, New York City, New York, USA,[48][49][50] MIT Museum, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA,[51] and ended in April 2019 at the Ackland Art Museum in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA.[52] The Beautiful Brain book, published by Abrams,[53] New York, accompanied the exhibition.

During 2019, the University of Zaragoza, Zaragoza, Spain opened an exhibition about Cajal titled Santiago Ramón y Cajal. 150 years at the University of Zaragoza. The exhibition had an accompanying catalog that featured the same title.[54] The exhibition opened October 2019 and closed at the end of December 2019.

A short documentary by REDES is available on YouTube.[55]

From November 19, 2020, to December 5, 2021, the National Museum of Natural Sciences, Madrid, Spain, hosted an exhibition featuring Cajal's scientific drawings, photographs, scientific equipment and personal objects from the Legado Cajal, Instituto Cajal, Madrid, Spain.[56]

In 2020, over 75 volunteers collaborated as part of The Cajal Embroidery Project across 6 countries to create 81 intricate, exquisite hand-stitched panels of Ramón y Cajal's images, which were then curated and displayed by Edinburgh Neuroscience at the virtual FENS 2020 Forum, and showcased by The Lancet Neurology in their front covers in 2021.[57]

In 2017, UNESCO (the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) recognised Cajal's Legacy (which had been kept in a museum from 1945 to 1989) as a World Heritage treasure. Recognising that this cultural treasure deserves a dedicated museum, showcasing not only Cajal's but also his disciples’ legacies, there has been a call for a dedicated museum to commemorate and celebrate Ramón y Cajal's discoveries and impact on neuroscience.[58]

Project Encephalon organised Cajal Week to celebrate his 169th birth anniversary from 1 May to 7 May 2021.[59]

The Brain In Search Of Itself,[60] an English language biography, was published in 2022.

Publications

[edit]He published more than 100 scientific works and articles in Spanish, French and German. Among his works were:[7]

- Rules and advice on scientific investigation

- Histology

- Degeneration and regeneration of the nervous system

- Manual of normal histology and micrographic technique

- Elements of histology

A list of his books includes:

- Ramón y Cajal, Santiago (1905) [1890]. Manual de Anatomia Patológica General (Handbook of general Anatomical Pathology) (in Spanish) (fourth ed.).

- Ramón y Cajal, Santiago; Richard Greeff (1894). Die Retina der Wirbelthiere: Untersuchungen mit der Golgi-cajal'schen Chromsilbermethode und der ehrlich'schen Methylenblaufärbung (Retina of vertebrates) (in German). Bergmann.

- Ramón y Cajal, Santiago; L. Azoulay (1894). Les nouvelles idées sur la structure du système nerveux chez l'homme et chez les vertébrés (New ideas on the fine anatomy of the nerve centres) (in French). C. Reinwald.

- Ramón y Cajal, Santiago; Johannes Bresler; E. Mendel (1896). Beitrag zum Studium der Medulla Oblongata: Des Kleinhirns und des Ursprungs der Gehirnnerven (in German). Verlag von Johann Ambrosius Barth.

- Ramón y Cajal, Santiago (1898). "Estructura del quiasma óptico y teoría general de los entrecruzamientos de las vías nerviosas. (Structure of the Chiasma opticum and general theory of the crossing of nerve tracks)" [Die Structur des Chiasma opticum nebst einer allgemeine Theorie der Kreuzung der Nervenbahnen (German, 1899, Verlag Joh. A. Barth)]. Rev. Trim. Micrográfica (in Spanish). 3: 15–65.

- Ramón y Cajal, Santiago (1899). Comparative study of the sensory areas of the human cortex. Clark University. p. 85.

- Ramón y Cajal, Santiago (1899–1904). Textura del sistema nervioso del hombre y los vertebrados (in Spanish). Madrid. ISBN 978-84-340-1723-8.

- —— (1909). Histologie du système nerveux de l'homme & des vertébrés (in French) – via Internet Archive.

- —— (2002-10-14). Texture of the Nervous System of Man and the Vertebrates. Springer. ISBN 978-3-211-83202-8.

- Ramón y Cajal, Santiago (1906). Studien über die Hirnrinde des Menschen v.5 (Studies about the meninges of man) (in German). Johann Ambrosius Barth.

- Ramón y Cajal, Santiago (1999) [1897]. Advice for a Young Investigator. Translated by Neely Swanson and Larry W. Swanson. Cambridge: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-68150-1.

- Ramón y Cajal, Santiago; Domingo Sánchez y Sánchez (1915). Contribución al conocimiento de los centros nerviosos de los insectos (in Spanish). Madrid: Imprenta de Hijos de Nicolas Moya.

- Ramón y Cajal, Santiago (1937). Recuerdos de mi Vida (in Spanish). Cambridge: MIT Press. ISBN 84-206-2290-7.

In 1905, he published five science-fiction stories called "Vacation Stories" under the pen name "Dr. Bacteria".[61][62]

Gallery of drawings

[edit]-

First illustration by Cajal (1888) of the nervous system. (A) First page of the article. (B) Vertical section of a cerebellar convolution of a hen. (C) Cerebellum of an adult bird. (D) Higher magnification of (C) showing Purkinje cell. (E) Dendrite of the Purkinje cell.

-

Drawing of the neural circuitry of the rodent hippocampus. Histologie du Système Nerveux de l'Homme et des Vertébrés, Vols. 1 and 2. A. Maloine. Paris. 1911

-

Drawing of the cells of the chick cerebellum, from "Estructura de los centros nerviosos de las aves", Madrid, 1905

-

Drawing of a section through the optic tectum of a sparrow, from "Estructura de los centros nerviosos de las aves", Madrid, 1905

-

From "Structure of the Mammalian Retina" Madrid, 1900

-

Drawing of Purkinje cells (A) and granule cells (B) from pigeon cerebellum by Santiago Ramón y Cajal, 1899. Instituto Santiago Ramón y Cajal, Madrid, Spain

-

Drawing of Cajal-Retzius cells, 1891

-

Drawn in 1899, taken from the book "Comparative study of the sensory areas of the human cortex"

-

schema of the visual map theory (1898). O=Optic chiasm; C=Visual (and motor) cortex; M, S=Decussating pathways; R, G: Sensory nerves, motor ganglia.

-

Purkinje cell of the human cerebellum. Golgi method. -a, axon; b, recurrent collateral; c and d, spaces in the dendritic arborization for stellate cells, by Santiago Ramón y Cajal.(see Fig. 9 in Ref.[63])

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b "Santiago Ramón y Cajal: The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1906". NobelPrize.org. Retrieved 2020-06-25.

- ^ a b c A Mind for Numbers. Tarcher Penguin. 2014. p. 193. ISBN 978-0-399-16524-5.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1906". NobelPrize.org.

- ^ "History of Neuroscience". Society for Neuroscience. Archived from the original on 2008-05-15. Retrieved 2008-10-09.

- ^ Santiago Ramón y Cajal, Recuerdos de mi Vida Volume I, Chapter X, Madrid Imprenta y Librería de N. Moya, Madrid 1917, online at Instituto Cervantes (Spanish)

- ^ a b c d Finger, Stanley (2000). "Chapter 13: Santiago Ramón y Cajal. From nerve nets to neuron doctrine". Minds behind the brain: A history of the pioneers and their discoveries. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 197–216. ISBN 0-19-508571-X.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Santiago Ramón y Cajal on Nobelprize.org , accessed 29 April 2020

- ^ Ramón y Cajal, Santiago (1917). "Recuerdos de mi vida. Volume I: Mi infancia y juventud. Chapter XXVII". Centro Virtual Cervantes cvc.cervantes.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 2024-07-20.

- ^ "Santiago Ramón y Cajal | Spanish histologist". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-06-25.

- ^ Ramón y Cajal, Santiago (1917). "Recuerdos de mi vida. Volume II: Historia de mi labor científica, Chapter II". Centro Virtual Cervantes cvc.cervantes.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 2024-07-20.

- ^ Newman, Eric (2017). The beautiful brain : the drawings of Santiago Ramón y Cajal. New York: Abrams. ISBN 978-1-4197-2227-1. OCLC 938991305.

- ^ Sherrington, C. S. (1935). "Santiago Ramón y Cajal. 1852–1934". Obituary Notices of Fellows of the Royal Society. 1 (4): 424–441. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1935.0007.

- ^ Yuste, Rafael (21 April 2015). "The discovery of dendritic spines by Ramón y Cajal". Frontiers in Neuroanatomy. 9 (18): 18. doi:10.3389/fnana.2015.00018. PMC 4404913. PMID 25954162.

- ^ a b José María López Piñero, "Santiago Ramón y Cajal", Universita de València

- ^ John Brande Trend (1965). The Origins of Modern Spain. Russell & Russell. p. 82.

Ramón y Cajal was a liberal in politics, an evolutionist in philosophy, an agnostic in religion...

- ^ Carolyn Sattin-Bajaj (2010). Marcelo Suarez-Orozco (ed.). Educating the Whole Child for the Whole World: The Ross School Model and Education for the Global Era. NYU Press. p. 165. ISBN 978-0-8147-4140-5.

In that sense, it was interesting to learn that Santiago Ramón y Cajal, the great pioneer of modern neuroanatomy, was agnostic, but still used the term soul without any shame.

- ^ DISCURSO DEL SR. D. SANTIAGO RAMÓN Y CAJALTEMA: FUNDAMENTOS RACIONALES Y CONDICIONES TÉCNICAS DE LAINVESTIGACIÓN BIOLÓGICA Sesquicentenario de Santiago Ramon y Cajal, 23 pages, p. 39-40: Y a los que te dicen que la Ciencia apaga toda poesía, secando las fuentes del sentimiento y el ansia de misterio que late en el fondo del alma humana, contéstales que á la vana poesía del vulgo, basada en una noción errónea del Universo, noción tan mezquina como pueril, tú sustituyes otra mucho más grandiosa y sublime, que es la poesía de la verdad, la incomparable belleza de la obra de Dios y de las leyes eternas por Él establecidas. Él acierta exclusivamente a comprender algo de ese lenguaje misterioso que Dios ha escrito en los fenómenos de la Naturaleza; y a él solamente le ha sido dado desentrañar la maravillosa obra de la Creación para rendir a la Divinidad uno de los cultos más gratos y aceptos a un Supremo entendimiento, el de estudiar sus portentosas obras, para en ellas y por ellas conocerle, admirarle y reverenciarle. [English Translation: P. 39-40: To those who tell you that Science quenches all poetry, drying up the sources of feeling and the longing for the mystery that pulses in the depths of the human soul, tell them that in the vain poetry of the people, based on an erroneous notion of Universe, as petty as it is puerile, you substitute a much more grandiose and sublime one, which is the poetry of truth, the incomparable beauty of the work of God and the eternal laws established by him. He is only able to understand something of that mysterious language that God has written in the phenomena of Nature; And he has only been able to unravel the wonderful work of Creation to render to the Divinity one of the most grateful and accepted cults to a supreme understanding, to study his portentous works, for them and for them to know, to admire and to revere him ]

- ^ "Las creencias de Darwin y Cajal | Amigos de Serrablo". Serrablo.org. 2009-03-31. Retrieved 2015-03-15.

- ^ Higgins, Edmund S. (16 February 2018). The neuroscience of clinical psychiatry : the pathophysiology of behavior and mental illness. George, Mark S. (Mark Stork), 1958– (Third ed.). Philadelphia. ISBN 978-1-4963-7202-4. OCLC 1048335337.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Santiago Ramón y Cajal: biografía del médico español más célebre". medsalud.com. 2019-09-18. Retrieved 2019-09-19.

- ^ "FANZCA part I notes on the Autonomic Nervous System". Anaesthetist.com. Retrieved 2015-03-15.

- ^ Ramón y Cajal, Santiago (1894-12-31). "The Croonian lecture.—La fine structure des centres nerveux". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. 55 (331–335): 444–468. doi:10.1098/rspl.1894.0063. ISSN 0370-1662.

- ^ López-Muñoz, F; Rubio, G; Molina, JD; García-García, P; Álamo, C; Santo Domingo, J (2007). "Cajal y la psiquiatría biológica: actividades profesionales y trabajos científicos de Cajal en el campo de la psiquiatría". Arch Psiquiatr (in Spanish). 70 (2): 83–114. ISSN 1576-0367. Archived from the original on September 16, 2017.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ramón y Cajal, Santiago (1898). "Estructura del quiasma óptico y teoría general de los entrecruzamientos de las vías nerviosas. (Structure of the Chiasma opticum and general theory of the crossing of nerve tracks)" [Die Structur des Chiasma opticum nebst einer allgemeine Theorie der Kreuzung der Nervenbahnen (German, 1899, Verlag Joh. A. Barth)]. Rev. Trim. Micrográfica (in Spanish). 3: 15–65.

- ^ Mora, Carla; Velásquez, Carlos; Martino, Juan (2019-09-01). "The neural pathway midline crossing theory: a historical analysis of Santiago Rámon y Cajal's contribution on cerebral localization and on contralateral forebrain organization". Neurosurgical Focus. 47 (3): E10. doi:10.3171/2019.6.FOCUS19341. ISSN 1092-0684.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1906". NobelPrize.org. Retrieved 2020-04-30.

- ^ J. S. Edwards & R. Huntford (1998). "Fridtjof Nansen: from the neuron to the North Polar Sea". Endeavour. 22 (2): 76–80. doi:10.1016/s0160-9327(98)01118-1. PMID 9719772.

- ^ "Santiago Ramon y Cajal". www.nasonline.org. Retrieved 2023-06-27.

- ^ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved 2023-06-27.

- ^ "Portrait of Santiago Ramon y Cajal (1852-1934) 1906 by Joaquin Sorolla y Bastida | Oil Painting | joaquin-sorolla-y-bastida.org". www.joaquin-sorolla-y-bastida.org. Retrieved 2021-05-22.

- ^ Giménez Roldan, S. (2019-01-01). "Monuments to Cajal in Madrid, Spain: Rejection of public tributes". Revue Neurologique. 175 (1): 2–10. doi:10.1016/j.neurol.2018.02.086. ISSN 0035-3787. PMID 30314743. S2CID 196532722.

- ^ Ramón y Cajal: Historia de una voluntad: Capítulo 1- Infancia y adolescencia | RTVE Archivo, retrieved 2021-05-22

- ^ Ramon Y Cajal, Santiago (2003). Santiago Ramon Y Cajal (1852–2003). La Casa Encendida, Madrid, Spain. ISBN 8495321467.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Severo Ochoa y Ramón y Cajal, Monumento a" (in Spanish). Retrieved 2021-05-22.

- ^ "Centro de Interpretación Ramón y Cajal de Ayerbe". Ayuntamiento de Ayerbe: guía de servicios, agenda, información municipal (in Spanish). Retrieved 2021-05-22.

- ^ "Santiago Ramón y Cajal Exhibit – history – Office of NIH History and Stetten Museum". history.nih.gov. Retrieved 2021-05-23.

- ^ Aggie, Mika (2017-08-13). "Reimagining Neuroscience's Finest Works of Art". The Scientist Magazine®. Retrieved 2021-05-22.

- ^ "Home | Fulbright Scholar Program". cies.org. Retrieved 2021-05-22.

- ^ "Dawn Hunter | Fulbright Scholar Program". cies.org. Retrieved 2021-05-22.

- ^ Hunter, Dawn (2017-11-14). "Drawn To, Drawn From Experience". Circulating Now from NLM. Retrieved 2021-05-22.

- ^ Hunter, Dawn (2018-10-02). "Communing and Giggling with Cajal". Circulating Now from NLM. Retrieved 2021-05-22.

- ^ Tuzlu su : düşünce biçimleri üzerine bir teori = Saltwater : a theory of thought forms. Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, Süreyya Evren, Ceyda Akaş Kabadayi, İstanbul Kültür ve Sanat Vakfı (2. Baski = ed.). Istanbul, Turkey. 2015. ISBN 978-605-5275-25-9. OCLC 933300635.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Fisiología de los sueños : Cajal, Tanguy, Lorca, Dalí... María García Soria, Jaime Brihuega, Universidad de Zaragoza. [Zaragoza]. 2015. ISBN 978-84-16515-15-8. OCLC 932125022.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Architecture of life. Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive. Berkeley, California. 2016. ISBN 978-0-9838813-1-5. OCLC 919068285.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Bridging the Legacy of Santiago Ramón y Cajal | National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke". www.ninds.nih.gov. Retrieved 2021-05-22.

- ^ García, Carmen (2018-02-06). "¿Quién recibe las Ayudas Ramón y Cajal?". elEconomista.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 2023-01-28.

- ^ "The Beautiful Brain: The Drawings of Santiago Ramón y Cajal". Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery. Retrieved 2021-05-22.

- ^ "The Beautiful Brain: The Drawings of Santiago Ramón y Cajal". Grey Art Gallery. 24 May 2016. Retrieved 2021-05-22.

- ^ Saltz, Jerry (2018-03-13). "This Nobel Laureate in Medicine Belongs Next to Michelangelo As a Draftsman". Vulture. Retrieved 2021-05-22.

- ^ Smith, Roberta (2018-01-18). "A Deep Dive Into the Brain, Hand-Drawn by the Father of Neuroscience". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2021-05-22.

- ^ MIT (2018). "Beautiful Brain".

- ^ Beautiful Brain: The Drawings of Santiago Ramón y Cajal The Weisman Art Museum, retrieved 9 August 2017

- ^ The beautiful brain : the drawings of Santiago Ramón y Cajal. Eric A. Newman, Alfonso Araque, Janet M. Dubinsky, Larry W. Swanson, Lyndel Saunders King, Eric Himmel. New York. 2017. ISBN 978-1-4197-2227-1. OCLC 938991305.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Santiago Ramón y Cajal : 150 años en la Universidad de Zaragoza : Paraninfo Universidad de Zaragoza, del 7 de octubre de 2019 al 11 de enero de 2020. Alberto J. Schuhmacher, José María. Serrano Sanz, María del Valle García Soria. Zaragoza: Prensas de la Universidad de Zaragoza, Vicerrectorado de Cultura y Proyección Social. 2019. ISBN 978-84-17873-98-1. OCLC 1138073534.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Documental sobre Santiago Ramón y Cajal en Redes YouTube, 34 min, Sep 22, 2012. (Spanish)

- ^ El CSIC exhibe parte del Legado Cajal en una exposición en el Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, archived from the original on 2021-12-12, retrieved 2021-05-22

- ^ Mehta, Arpan R; Abbott, Catherine M; Chandran, Siddharthan; Haley, Jane E (December 2020). "The Cajal Embroidery Project: celebrating neuroscience". The Lancet Neurology. 19 (12): 979. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30348-3. PMC 7116532. PMID 32949529.

- ^ DeFelipe, Javier; De Carlos, Juan A; Mehta, Arpan R (January 2021). "A museum for Cajal's Legacy". The Lancet Neurology. 20 (1): 25. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30444-0. PMC 7116571. PMID 33340480.

- ^ "Cajal Week". Project Encephalon. Retrieved 21 April 2021.

- ^ Ehrlich, Benjamin (2022). The Brain In Search Of Itself. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 9780374110376.

- ^ Otis, Laura (11 March 2007). "Dr. Bacteria". LabLit.com/article/226; Published 11 March 2007.

- ^ Ramón y Cajal, Santiago (1906). Vacation stories: five science fiction tales. Translated by Otis, Laura. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-02655-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Santiago Ramón y Cajal, "Texture of the Nervous System of Man and the Vertebrates, Volume 1" Originally published by Springer-Verlag Wien New York in 1999

References

[edit]- Everdell, William R. (1998). The First Moderns. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-22480-5.

- Mazzarello, Paolo (2010). Golgi: A Biography of the Founder of Modern Neuroscience. Translated by Aldo Badiani and Henry A. Buchtel. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-533784-6.

Further reading

[edit]- Wilkinson, Alec, "Illuminating the Brain's 'Utter Darkness'" (review of Benjamin Ehrlich, The Brain in Search of Itself: Santiago Ramón y Cajal and the Story of the Neuron, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2023, 447 pp.; and Timothy J. Jorgensen, Spark: The Life of Electricity and the Electricity of Life, Princeton University Press, 2021, 436 pp.), The New York Review of Books, vol. LXX, no. 2 (February 9, 2023), pp. 32, 34–35.

External links

[edit]- Fishman, R. S. (2007). "The Nobel Prize of 1906". Archives of Ophthalmology. 125 (5): 690–694. doi:10.1001/archopht.125.5.690. PMID 17502511. (Review of the work of the 1906 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine winners Camillo Golgi and Santiago Ramón y Cajal)

- Santiago Ramón y Cajal on Nobelprize.org including the Nobel Lecture on December 12, 1906 The Structure and Connexions of Neurons

- Ramón y Cajal, Santiago (December 12, 1906). "The structure and connexions of neurons" (PDF). The Nobel Prize. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- Marina Bentivoglio Life and discoveries of Cajal Nobel Prizes and Laureates, 20 April 1998

- Cajal's Láminas ilustrativas Centro Virtual Cervantes

- Javier de Felipe Brief overview of Ramón y Cajal's career www.psu.edu The Pennsylvania State University, 1998

- Newspaper clippings about Santiago Ramón y Cajal in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- Fields, R. Douglas (September 28, 2017). "Why the First Drawings of Neurons Were Defaced". Quanta Magazine.

- 1852 births

- 1934 deaths

- People from Navarre

- Former atheists and agnostics

- 20th-century Spanish physicians

- 19th-century Spanish physicians

- Spanish neuroscientists

- History of neuroscience

- Nobel laureates in Physiology or Medicine

- Spanish Nobel laureates

- Spanish pathologists

- Spanish anatomists

- Spanish military doctors

- Histologists

- Spanish Freemasons

- Members of the Royal Spanish Academy

- Complutense University of Madrid alumni

- Foreign members of the Royal Society

- Foreign associates of the National Academy of Sciences

- Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (civil class)

- University of Zaragoza alumni

- Members of the American Philosophical Society

- Academic staff of the Complutense University of Madrid