Santa Maria Antiqua

| Santa Maria Antiqua al Foro Romano | |

|---|---|

| Ancient Church of Saint Mary in the Roman Forum | |

Oratory of the Forty Martyrs, by the entrance to Santa Maria Antiqua in the Forum Romanum | |

Click on the map for a fullscreen view | |

| 41°53′27.6″N 12°29′8.1″E / 41.891000°N 12.485583°E | |

| Location | Rome |

| Country | Italy |

| Denomination |

|

| History | |

| Status | Inactive |

| Consecrated | 5th century |

| Architecture | |

| Style | Byzantine architecture |

| Groundbreaking | 5th century |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 30 metres (98 ft) |

| Width | 20 metres (66 ft) |

Santa Maria Antiqua (English: Ancient Church of Saint Mary) is a Catholic Marian church in Rome, Italy, built in the 5th century in the Forum Romanum, and for a long time the monumental access to the Palatine imperial palaces.

Located at the foot of the Palatine Hill, Santa Maria Antiqua is the oldest Christian monument in the Roman Forum. The church contains the earliest Roman depiction of Santa Maria Regina, the Virgin Mary as a Queen, from the 6th century.[1][2][3]

History

[edit]Built in the middle of the 5th century on the north-western slope of the Palatine Hill, Santa Maria Antiqua is the earliest and most significant Christian monument within the Roman Forum. The church contains a unique collection of wall paintings from the 6th to late 8th century. The discovery of these paintings have given many theories on the development of early medieval art and given distinctive beliefs in archaeology. The church was abandoned in the 9th century after an earthquake buried the buildings; it remained sealed for over 1000 years until its rediscovery in the early 20th century. Therefore, Santa Maria Antiqua represents a key element for the understanding of the cultural and urban development of the Roman Forum from Antiquity into the first centuries of the Christian period. From 1980 to 2012 the monument was closed to the general public and limited to scholars who applied for a special visit. Following a conservation program carried out by the Soprintendenza per il Patrimonio Storico in partnership with World Monuments Fund, the church is now open for tours.

Santa Maria Antiqua is a ruined church in the Roman Forum, and is part of the Foro Romano e Palatino archaeological site which requires a ticket purchase in order to get access inside. The church itself is not always open to the public, owing to ongoing excavations which began 2004 under the aegis of the World Monuments Fund. Thanks to centuries of sealing off, its walls showcase a cycle of beautiful colourful frescoes depicting the Virgin Mary and Infant Jesus, popes, saints, and martyrs, thus forming one of the largest and most important collections of pre-iconoclastic Roman and Byzantine art in the world. These frescoes date to a period of iconoclasm when in the East, figures in churches were destroyed.[4]

Pope John VII used this church in the early 8th century as the seat of the bishop of Rome.

The church was partially destroyed in 847, when an earthquake caused parts of the imperial palaces to collapse and cover the church. For this reason, a new church called Santa Maria Nova (New St Mary, now Santa Francesca Romana) was erected nearby by Pope Leo IV, on a portion of the ruined temple of Temple of Venus and Roma, where once stood a chapel commemorating the fall of Simon Magus.[5] Santa Maria Antiqua suffered further damages during the Norman Sack of Rome (1084).

Prior to the present structures, the church of San Salvatore in Lacu, occupied by Benedictines, was located at this site, named because of its proximity to a site called the Lago di Gioturna. The church was assigned in 1550 by Pope Julius III to the Oblates of St Frances of Rome from the nearby Monastery of Tor de' Specchi.[6] The church of Santa Maria Liberatrice (Sancta Maria libera nos a poenis inferni) was built in 1617 on its ruins of Santa Maria Antiqua. This refurbishment was patronized by Cardinal Marcello Lante della Rovere and utilized the architect Onorio Longhi. The church was decorated by the painters Stefano Parrocel, Gramiccia (Lorenzo?), Francesco Ferrari, and Sebastiano Ceccarini.[7] The church of Maria Liberatrice, however, was demolished in 1900 to bring the remains of the old church to light.[8]

Santa Maria Antiqua was closed for restoration from 1980 to 2016.

Byzantine frescoes

[edit]The heavily layered walls of Santa Maria Antiqua host numerous frescoes of varying artistic style and adaption during its time of intense decoration from the sixth to the ninth century.[9] Each alcove, wall and altar can be attributed to different times and trends of style representative of its artists and patrons, including the Popes Martin I (649-653), John VII (705-707), Zachary (741-752) and Paul I (757-767). The amount of erosion and destruction makes obtaining an accurate record of the styles difficult. Using the fragments of the frescoes, archaeologists and historians have assembled a rough chronology of the decorations.[10] Historians who study Santa Maria Antiqua often rely on contemporary churches to help create a chronology of styles and influences: in the case of Santa Maria Antiqua, this is less successful due to the fact that no other church from Late Antiquity has quite the same collection and evolution of styles through this time.[11] The change of style at Santa Maria Antiqua is recognized through its layering of trends and styles.

Rome changed hands multiple times during Santa Maria Antiqua's use. The defeat of the Western Roman Empire by the Goths in the fifth century gave way to Byzantine and Lombard influence in the late fifth to mid eighth centuries.[12] Artists from the Greek community surrounding the church had local influence, but there was also a Byzantine administration operating atop the Palatine Hill, at the base of which is Santa Maria Antiqua.[13] This continual change in influences is thought to be a determining factor in the different styles in this church.[14] Influences can also be traced through remaining inscriptions: Greek in Pope Martin I's (649-653) decorations, Greek and Latin in Pope John VII's (705-707) and completely Latin in Pope Paul I's.[15]

The Palimpsest Wall, located in the sanctuary (number two on map) has at least six layers of decoration, representing different styles, dates and influences.[16] The first two layers from the fourth to sixth century are of Ancient Roman Pagan mosaics, which quickly were replaced by the earliest frescoes of Santa Maria Antiqua.[17] About two percent of these mosaics survive because they were overpainted with fresco.[18] The third layer, c. 500-550, contains remnants of Queen of Heaven, the earliest association of this title with the Virgin Mary and the Pompeian Angel.[19][20] It is on this layer that archaeologists note the turn toward Hellenistic or Byzantine styles and away from a traditional linear Roman style.[20] Layers four and five, c. 570-655 see the complete take over of Hellenistic style from earlier Roman styles, asserting Byzantine influence in Rome.[20] Layer six belongs to Pope John VII (705-707) who is responsible for the extensive repairs and decorations that currently survive.[20]

Hellenistic style is notable for white highlighting and shadowing of hair and robes along with placing figures is stances of motion.[21] Although many of the surviving frescoes at Santa Maria Antiqua are Hellenistic, they lack classical Hellenistic backgrounds of villas and columns.[22] Instead, the backgrounds are more detached and neutral looking.[23] Early examples often have the blackened pupils staring straight ahead with contour details on the face. The first stage of each frescoes involved penciling in outlines, then the darker colours would be added as clothing while the finer details were finished last.[24] Hellenism began to manifest itself during the time the Pompeian Angel was painted and eclipsed the more Pagan styles by AD 650.[25]

The eras of Popes Martin I (649-653), John VII (705-707) and Paul I (757-767) provide clear examples of the stylistic trends through their surviving decorations. The surviving frescoes exemplify the ability of the artists to incorporate different techniques and styles; consequently, these styles soon became unique as generations of artists formed specific skill sets for Santa Maria Antiqua to continue or discontinue trends seemingly at random.[26]

The Martin I (649-653) frescoes are few but reasonably preserved. These in Hellenistic style as it had fully eclipsed the traditional Roman style by the time he entered office, which was after the Byzantines had taken over.[25] Roman style was much less detailed: no contour lines or shading and very subdued backgrounds.[27] The earliest Martin I decorations are the Church Fathers AD 649 who are expressing movement by having a leg lifted in the walking motion while their robes are draped and highlighted to exaggerate this effect.[28] The Church Fathers are exemplifying more fluidity with their tunics swirling than compared to later frescoes but their faces are much stiffer, also compared to later frescoes.[29] The precise date is referenced by a Greek inscription below as pertaining to the Lateran Council of 649 that condemned Monothelitism.[30] Martin I was ultimately exiled for his condemnation of Monothelitism but John VII commissioned his image to be painted in the Presbytery (see map) with other images of popes in Santa Maria Antiqua.[31] Martin I is depicted in Hellenistic fashion by white brush strokes shading his brown facial hair that is painted on a heavily contoured, emaciated jaw and he carries a jewelled book.[32] He wears an ecclesiastical hairstyle that is balding, short and has a central lock of hair around the forehead.[32] Martin I's eyes are not staring straight ahead with jet-black pupils as was typical of contemporaries, instead they are gazing downward and individualized.[32] Most notably is that Martin I and John VII's images are clothed in the same colour paenula of light yellow with green underlay showing through, suggesting a sort of solidarity among the popes against the Byzantines, using art to convey political messages that the Byzantine decision to exile Martin I was wrong.[33]

The period of Pope John VII (705-707) has the most surviving decorations.[34] These provide examples of techniques used during Santa Maria Antiqua's extensive repairs and redecorations of the Presbytery, Chapel of Physicians (or Chapel of Medical Saints) and the Oratory of Forty Martyrs.[34] John VII's ambitious projects can be partially blamed for the removal and destruction of existing frescoes as his artists often re-plastered the areas approximately 4.5 meters and up.[35] Holes drilled into the walls at even intervals and levels remain to provide details of how this was accomplished in such small, cramped spaces.[35] The artists would drill holes into the walls 9.3 meters above the floor to hold their scaffolding then spread intonaco (plaster) to reinforce and secure layers below the current working surface.[35] Painting took place immediately after the intonaco was spread in order to allow the paint to seep into the plaster for a deeper effect.[35] The same holes would then be drilled lower, 7.98 meters above the floor and the process repeated. Thus the majority of surviving frescoes in Santa Maria Antiqua were painted top-to-bottom instead of side-to-side or at once. Complex, detailed frescoes were needed where intonaco was spread because it would overlap with existing frescoes causing lines, easily shown in the details of Hellenistic styled frescoes. The new complex designs would help hide the lines and cracks that was caused by the intonaco.[35]

The John VII decorations feature Hellenistic styles fused with earlier Roman linear styles.[36] Although John VII's frescoes are adorned with breezy tunics, toned contours of flesh and animated expressions that individualized the saints, they are considered by archaeologists and historians to be strained in their movement.[37][38] The artists posed them in conversation with quick hands and turned heads but their backs are "flat" against the background instead of turning inwards toward the conversation.[39] An example of this detail comes in the form of Saint Hermolaus of Macedon in the Chapel of Physicians who is pictured with high, strongly contoured cheekbones, asymmetrical eyes, arching eyebrows with highlighted long, dark hair and a flowing beard.[40] There are no known contemporary parallels to Santa Maria Antiqua's use of white highlighting that is common here.[41] John VII's artists were very influenced by the Byzantines as they combine the transparency of Hellenism with denser, layered colours.[42]

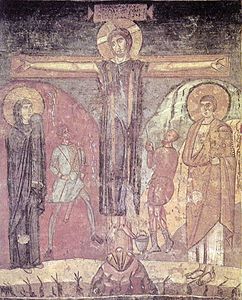

The most controversial figure from the period of John VII, Christ in the Adoration of the Cross/Crucified, located in the Triumphal Arch.[32][43] This figure is approximately 2.5 meters high and poorly preserved: Christ's head, abdomen and left arm survive.[44] Flanking Christ on the cross are angels, Saint John's head with halo and there is a crown of adoring followers dressed in different coloured robes at the foot of a cliff (believed to be Golgotha, from Matthew 27: 33).[44] Christ's image does not conform to contemporary images or other portrayals of Christ by John VII: in Santa Maria Antiqua he is seen as having curly, short hair, lightly thatched facial hair and wearing a loincloth.[45] Contemporary images show Christ having long hair with a long beard and wearing a colobium (a linen shift).[45] The origin of this new portrayal is thought to have come from the coins issued by Justinian II after he reasserted Byzantine rule in Italy in AD 705.[45] The coins were minted in Italy, and like the fresco, they depict Christ with short hair and a barely-there beard, following Byzantine fashion.[45] Possible influence of the coins appears in Christ's eyes: like on the coin, they are wide open, staring straight ahead instead of shut or downcast.[45] The existence of the loincloth was established by close examination of the fresco, which revealed a heavily contoured or muscled abdomen that would not have been consistent with fabric patterns of a colobium.[32] From the two different images of Christ in circulation at this time, from the west and from the east, it is possible to suggest that the Byzantine artist community living on Palatine Hill by Santa Maria Antiqua held influence in the painting of the Adoration of the Cross/Crucified.[46]

The 'Chapel of Physicians' or 'Chapel of Medical Saints' is another of John VII's works that survives, although poorly in comparison to his others.[47] The chapel hosts numerous, life-sized saints with their common appearance of brown tunics, long, dark hair, long beards, wide open eyes, animated eyebrows and sandals, each saint is holding a scroll in their right hand and varying styles of surgeon boxes with black straps.[47] These details are gleaned from the pieces of individual saints in the chapel, as no individual saint survives intact. There is no contemporary example of this chapel or a collection this diverse of medical saints.[48] Originating around the mid seventh century, medical saints are believed to have encouraged people to stop seeking pagan cures for illness and turn to Christian prayers by identifying themselves with a particular saint.[49] This would have been easily accomplished at Santa Maria Antiqua due to the diverse community surrounding the church and the diversity of medical saints, thus making religion accessible, relatable and understandable.[50] Included in the collection of saints are: Saint Dometius of Persia, a hermit known for miracles, Saints Cosmas and Damian, physicians claimed to appear to the ill who prayed to them, Nazarius and Celsus, martyrs from Gaul.[51] These icons are reproductions made for the easiest access to the Byzantine influenced practice of incubation (the notion that while sleeping in a church, one could see a saint or be cured of disease) that was popular in the early eighth century.[50] The ease in accessibility of these medical saints of all different origins encouraged people to recover from illness in a Christian way, replacing any traces that Santa Maria Antiqua was associated with pagans but still continuing its reputation for being a place of healing.[52]

The saints in Martin I's era were all in frames and sequences of movement with flowing designs, light colours and patterned backgrounds, John VII's era were still in frames of motion but they were more detailed: his designs were slightly linear in the old Roman style and his backgrounds were nondescript.[29] Even though John VII's decorations conform to the Hellenistic style, they are showing a slow shift back to the old Roman traditions that are dominant in the decorations from the era of Paul I.

Paul I's (757-767) Saint Abbakyros in the atrium was created after the Lombards succeeded in destroying the Byzantine government in Italy and during the Iconoclasm period in the east.[53] Saint Abbakyros is well preserved with hard, stiff brush strokes.[53] His face has asymmetrical eyes with arching eyebrows, a wrinkled forehead and a beard.[53] The finer details of eyelashes are indistinguishable from shadows, no highlights accenting his hair or beard and a stiff pose represent Roman bulkiness with this lack of detail.[54] His mouth is a series of lines due to the lack of shading and detailing; Paul I's Saint Abbakyros clearly lacks the finder details of the earlier frescoes.[53] The Hellenistic trend and Byzantine influence on art had seemingly wanted by this time, returning to a more Roman style. By simplifying the style, Paul I appeased those of Byzantine origin left in Rome who were in the throes of Iconoclastic debates.

The progression of styles at Santa Maria Antiqua started as pagan mosaics, turned into a classical revival of Hellenistic styles with fluidity, light, colours and motion that evolved into deeper colours and finer detail, finally morphing into less detailed and rigid: an almost backwards evolution. The shift in trends can correspond to Byzantine influences and tensions within Italy from the fifth to ninth centuries.[55] Difficulties in establishing chronologies are the result of poor preservation, changes in style and the partial decoration or redecoration during each phase.[56] Ultimately it was the Byzantine-influenced popes and artists at Santa Maria Antiqua who were most important; however, it is the artists' adaption of technique that survives as a tribute to their skill. Santa Maria Antiqua hosts a collection of frescoes in fragments that clearly make it one of a kind in Late Antiquity by its inclusion of all styles, techniques and influences or lack of influence as it does not quite fit with contemporaries.

-

Sant'Abbaciro (Saint Cyrus)

-

Fresco in Santa Maria Antiqua

-

Detail: Angel of the Annunciation (On the Palimpsest Wall) (565-578)

-

Crucifixion (741-752)

-

Crucifixion from Santa Maria Antiqua

See also

[edit]- Catholic Marian church buildings

- Elisabetta Povoledo, "Early Christian Church in Rome Reopens to Public" New York Times, March 17, 2016. Retrieved: 2016-03-20.

References

[edit]- ^ Erik Thunø, 2003 Image and relic: mediating the sacred in early medieval Rome ISBN 88-8265-217-3 page 34

- ^ Bissera V. Pentcheva, 2006 Icons and power: the Mother of God in Byzantium ISBN 0-271-02551-4 page 21

- ^ Anne J. Duggan, 2008 Queens and queenship in medieval Europe ISBN 0-85115-881-1 page 175

- ^ "Welcome back, Santa Maria Antiqua". American Institute for Roman Culture. 2012-10-03.

- ^ Benigni, U. (1913). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Guida metodica di Roma e suoi contorni, by Giuseppe Melchiorri, Rome (1836); page 427.

- ^ Melchiorri; pages 427=428.

- ^ Horace, K. (1913). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Folgero, Olav. "The Lowest, Lost Zone in the Adoration of the Crucified Scene in Santa Maria Antiqua in Rome: A New Conjecture". Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, 2009, p. 207.

- ^ Nordhagen, Per Jonas. "The Frescoes of John VII (A.D. 705-707) In S. Maria Antiqua in Rome". 1986, p. 4.

- ^ Knipp, David. "The Chapel of Physicians at Santa Maria Antiqua". Dumberton Oak Papers, 2002, p. 15.

- ^ Frothingham Jr., A.L. "Notes on Byzantine Art and Culture in Italy and Especially in Rome". The American Journal of Archaeology and of the History of the Fine Arts, 1895, p. 152, 157.

- ^ Knipp 2002, p. 2.

- ^ Maguire, Henry. "Style and Ideology in Byzantine Imperial Art". Gesta, 1989, p. 217.

- ^ Avery, Myrtilla. "The Alexandrian Style at Santa Maria Antiqua, Rome". The Art Bulletin, 1925, p. 137.

- ^ Nordhagen, Per Jonas. "Studies in Byzantine and Early Medieval Painting". Pindar Press, 1990, p. 163.

- ^ Nordhagen, Studies, p. 175.

- ^ Nordhagen 1990, p. 158.

- ^ Osborn, John. "The Atrium of S. Maria Antiqua, Rome: A History in Art". Papers of the British School at Rome, 1987, p. 195.

- ^ a b c d Nordhagen 1990, p. 175.

- ^ Avery 1925, p. 135.

- ^ Nordhagen 1990, p. 309.

- ^ Avery 1925, p.137.

- ^ Osborne 1987, p. 192.

- ^ a b Nordhagen 1990, p. 308.

- ^ Nordhagen 1990, p. 465.

- ^ Nordhagen 1968, p. 104.

- ^ Nordhagen 1968, p. 119.

- ^ a b Nordhagen 1968, p. 106.

- ^ Osborne 1986, p. 188.

- ^ Osborn 1986, p. 188.

- ^ a b c d e Nordhagen 1968, p. 43.

- ^ Maguire 1989, p. 217.

- ^ a b Nordhagen 1968, p. 87.

- ^ a b c d e Nordhagen 1990, p. 169.

- ^ Nordhagen 198, p. 113.

- ^ Osborne 1987, p. 187.

- ^ Nordhagen 1968, p. 101.

- ^ Nordhagen 1968, p. 194.

- ^ Knipp 2002, p. 14.

- ^ Nordhagen 1968, p. 113.

- ^ Nordhagen 1968, p. 106, 118.

- ^ Nordhagen, Per Jonas. "John VII's Adoration of the Cross in S. Maria Antiqua". Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, 1967, p. 388.

- ^ a b Nordhagen 1967, p. 388.

- ^ a b c d e Nordhagen 1967, p. 389.

- ^ Frothingham Jr. 1895, p. 175.

- ^ a b Knipp 2002, p. 3.

- ^ Knipp 2002, p. 6.

- ^ Knipp 2002, p. 9, 10.

- ^ a b Knipp 2002, p. 9.

- ^ Knipp 2002, p. 3, 13.

- ^ Knipp 2002, p. 8.

- ^ a b c d Knipp 2002, p. 17.

- ^ Avery 1925, p. 136.

- ^ Frothingham Jr. 1895, 152, 157.

- ^ Nordhagen 1990, p. 150.

Sources

[edit]- Horace, K. (1913). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Benigni, U. (1913). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- David, Joseph (1911). Sainte Marie-Antique; étude liturgique et hagiographique avec un plan de l'église (in French). Rome: M. Bretschneider.

- Webb, Matilda (2001). "Santa Maria Antiqua". The Churches and Catacombs of Early Christian Rome. Brighton: Sussex Academic Press. pp. 112–122. ISBN 1-902210-58-1.

- Santa Maria Antiqua Project. "Santa Maria Antiqua: history from antiquity until the year 847 A.D." Soprintendenza Archeologica di Roma. Archived from the original on 2007-08-11. Retrieved 2009-06-13.

- Romanelli, Pietro; Nordhagen, Per Jonas (1999). S. Maria Antiqua (in Italian) (2 ed.). Roma: Ist. poligrafico dello Stato, Libreria dello Stato. ISBN 88-240-3719-4.

- Angiolino, Loredana (2004). "Santa Maria Antiqua: Chiesa Bizantina a Roma". Bollettino Telematico dell'Arte (in Italian) (363). ISSN 1127-4883.

- Claridge, Amanda (1998). Rome: An Oxford Archaeological Guide. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-288003-9.

- Avery, Myrtilla (1925). "The Alexandrian Style at Santa Maria Antiqua, Rome". The Art Bulletin. 7 (4): 131–149. doi:10.2307/3046494. JSTOR 3046494.

- Folgero, Olav (2009). "The Lowest, Lost Zone in the Adoration of the Crucified Scene in Santa Maria Antiqua in Rome: A New Conjecture". Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes. 72: 207–219. doi:10.1086/JWCI40593769. S2CID 192676164.

- Frothingham Jr, A.L. (1895). "Notes on Byzantin Art and Culture in Italy and Especially in Rome". The American Journal of Archaeology and of the History of the Fine Arts. 10 (2): 152–208. doi:10.2307/496574. JSTOR 496574.

- Knipp, David (2002). "The Chapel of Physicians at Santa Maria Antiqua". Dumbarton Oaks Papers. 56: 1–23. doi:10.2307/1291851. ISSN 0070-7546. JSTOR 1291851.

- Maguire, Henry (1989). "Style and Ideology in Byzantine Imperial Art". Gesta. 28 (2): 217–231. doi:10.2307/767070. JSTOR 767070. S2CID 192603210.

- Nordhagen, Per Jonas (1967). "John VII's Adoration of the Cross in S. Maria Antiqua". Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes. 3: 388–390. doi:10.2307/750753. JSTOR 750753. S2CID 195050350.

- Nordhagen, Per Jonas (1968). The Frescoes of John VII (A.D. 705-707) In S. Maria Antiqua in Rome. Rome.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Nordhagen, Per Jonas (1990). Studies in Byzantine and Early Medieval Painting. London: Pindar Press. ISBN 978-0-907132-47-9.

- Osborne, John (1987). "The Atrium of S. Maria Antiqua, Rome: A History in Art". Papers of the British School at Rome. 55: 186–223. doi:10.1017/s0068246200009004. S2CID 191364070.

Further reading

[edit]- Lucey, Stephen J. (2007). "Art and Socia-Cultural Identity in Early Medieval Rome - The Patrons of Santa Maria Antiqua". In O'carragain, Eamonn; Neuman de Vegvar, Carol L. (eds.). Roma Felix: formation and reflections of medieval Rome. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing Ltd. pp. 139–158. ISBN 978-0-7546-6096-5.

- Osborne, J.; Brandt, G.; Morganti, eds. (2005). Santa Maria Antiqua al Foro Romano cento anni dopo. Campisano Editore. ISBN 88-88168-21-4.