Sutton Coldfield

| The Royal Town of Sutton Coldfield | |

|---|---|

Clockwise from top: Sutton Coldfield Church Gardens, Holy Trinity Church, Sutton Park, Town Hall and Parade | |

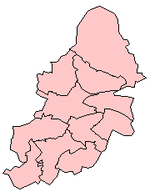

Location within the West Midlands | |

| Population | 109,899 (2021 Census)[1] |

| OS grid reference | SP1395 |

| Civil parish |

|

| Metropolitan borough | |

| Shire county | |

| Metropolitan county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Areas of the town | List

|

| Post town | SUTTON COLDFIELD |

| Postcode district | B72 – B76 |

| Dialling code | 0121 |

| Police | West Midlands |

| Fire | West Midlands |

| Ambulance | West Midlands |

| UK Parliament | |

Sutton Coldfield or the Royal Town of Sutton Coldfield (/ˌsʌtən ˈkɒldfiəld/ ),[3][4] is a town and civil parish in the city of Birmingham, West Midlands, England. The town lies around 8 miles northeast of Birmingham city centre, 9 miles south of Lichfield, 7 miles southwest of Tamworth, and 7 miles east of Walsall.

Sutton Coldfield and its surrounding suburbs are governed under Birmingham City Council for local government purposes but the town has its own town council which governs the town and its surrounding areas by running local services and electing a mayor to the council. It is in the historic county of Warwickshire, and in 1974 it became part of Birmingham and the West Midlands metropolitan county under the Local Government Act 1972.

History

[edit]Etymology

[edit]The etymology of the name Sutton appears to be from "South Town".

The name "Sutton Coldfield" appears to come from this time, being the "south town" (i.e. south of Tamworth and/or Lichfield) on the edge of the "col field". "Col" is usually derived from "charcoal", charcoal burners presumably being active in the area.[5]

Prehistory

[edit]The earliest known signs of human presence in Sutton Coldfield were discovered in 2002–2003 on the boundaries of the town.[6] Archaeological surveys undertaken in preparation for the construction of the M6 Toll road revealed evidence of Bronze Age burnt mounds near Langley Mill Farm, at Langley Brook. Additionally, evidence for a Bronze Age burial mound was discovered, one of only two in Birmingham with the other being located in Kingstanding. Excavations also uncovered the presence of an Iron Age settlement, dating to around 400 and 100 BC,[7] consisting of circular houses built over at least three phases surrounded by ditches.[8][9] Closer to Langley Brook (a tributary of the River Tame), excavations uncovered the remains of a single circular house surrounded by ditches, dating from the same period.[7]

Near to Langley Mill Farm is Fox Hollies, where archaeological surveys have uncovered flints dating from the New Stone Age. Amongst the finds in the area were flint cores and a flint scraper, which had been retouched with a knife. The presence of flint cores suggest that the site was used for tool manufacture and that a settlement was nearby. Additionally, a Bronze Age burnt mound was also discovered in the area.[10]

In his History of Birmingham, published in 1782, William Hutton describes the presence of three mounds adjacent to Chester Road on the extremities of Sutton Coldfield (although now outside the modern boundaries of the town).[11] The site, southwest of Bourne Pool (named "Bowen Pool" by Hutton[11]), is called Loaches Banks and was mapped as early as 1752 by Dr. Wilks of Willenhall. Hutton interpreted the earthworks as a Saxon fortification but further archaeological work led Dr. Mike Hodder, now the Planning Archaeologist for Birmingham City Council, to believe that the site was an Iron Age hill-slope enclosure. Centuries of agriculture on the land has severely affected the visibility of the features, with the earthworks now only apparent in aerial photography.[12]

Further evidence of pre-Roman human habitation are preserved in Sutton Park. A major fire in the park in 1926 revealed six more mounds near Streetly Lane, excavations of which uncovered charred and cracked stones within them and pits below the two largest mounds.[13] Although their date of origin is unknown, claims they were of Bronze Age origin were disproved.[14] The mounds are now covered in rough heathland.[15] The area around Rowton's Well has been the source of many archaeological discoveries such as flint tools, and in the 18th century, worked timbers were discovered near the well, suggesting a possible Iron Age timber trackway built across wet land, similar to others discovered elsewhere in the country.[13] A burnt mound was also discovered in New Hall Valley.[16]

Roman period

[edit]The presence of Romans in the area is most visible in Sutton Park, where a 1.5-mile (2.4 km) long preserved section of Icknield Street passes through. Whilst the road ultimately connects Gloucestershire to South Yorkshire, locally, the road was important for connecting Metchley Fort in Edgbaston with Letocetum, now Wall, in Staffordshire. The road is most visible from near to the pedestrian gate on Thornhill Road (OS Grid Reference SP 08759 98830), where the 8 m (26 ft) wide bank that formed the road surface is most prominent. Excavations at the road have showed that it was made from compacted gravel, never having a paved surface. Along each side are intermittent ditches, marked by Roman engineers, and beyond these are hollows where gravel was excavated to make the road surface.[13] At least three Roman coins have been found along the course of Icknield Street through Sutton Park,[17] as well as a Roman pottery kiln elsewhere in the town.[18]

Next to the Iron Age property at Langley Brook, the remains of a timber building and field system were discovered. Pottery recovered from this site was dated to the second and third century, indicating the presence of a Roman farmstead.[7]

Anglo-Saxon establishment, c. 600–1135

[edit]Upon the Roman withdrawal from Britain to protect the Roman Empire on the continent in the fifth century, the area of Sutton Coldfield, still undeveloped, passed into the Anglo Saxon kingdom of Mercia. It is during this period that it is believed Sutton Coldfield may have originated as a hamlet, as a hunting lodge was built at Maney Hill for the purpose of the Mercian leaders.[19] The outline of the deer park that it served is still visible within Sutton Park, with the ditch and bank boundary forming the western boundary of Holly Hurst, then crossing Keepers Valley, through the Lower Nuthurst and continuing on south of Blackroot Pool. Due to the marshy ground at Blackroot Valley, a fence was probably constructed to contain the deer, and the ditch and bank boundary commence again on the eastern side, on towards Holly Knoll.[15]

This became known as Southun or Sutton; "ton" meaning the town stead to the south of Tamworth, the capital of Mercia. Middleton is situated between the two. "Coldfield" denotes an area of land on the side of hill that is exposed to the weather.

Sutone, as the manor became known, was held by Edwin, Earl of Mercia, during the reign of Edward the Confessor. Upon the death of Edwin in 1071, the manor and the rest of Mercia passed into the possession of the Crown, then ruled by William the Conqueror, resulting in Sutton Chase becoming a Royal Forest.[20]

The manor of Sutone was mentioned in the Domesday Book of 1086, where it was rated at eight hides, making it larger than all surrounding villages in terms of cultivated land.[21]

Early development, c. 1135–1499

[edit]Possession of the manor

[edit]The manor remained in the possession of the Crown until 1135,[21] when King Henry I exchanged it for the manors of Hockham and Langham in Rutland, with Roger de Beaumont, 2nd Earl of Warwick.[20] The manor remained in the possession of the earldom of Warwick for around 300 years, with numerous exceptions.[21] As Sutton Forest was no longer in the possession of the Crown, it became Sutton Chase.

In 1242, when the manor was passed to Ela Longespee, the widow of Thomas de Beaumont, 6th Earl of Warwick, it was named as Sutton-in-Coldfield, and again noted as such in 1265 when Ela married her second husband Philip Basset. The manor of Sutton-in-Coldfield was once again in the possession of the earldom of Warwick when Ela exchanged it with William de Beauchamp, 9th Earl of Warwick, for the manor of Spilsbury in Oxfordshire.[20] The first mention of a manor house attached to the manor of Sutton was mentioned in 1315 on a site named Manor Hill, west of the parish church.[20]

During the 15th century, Sutton Coldfield underwent a process of change due in part to the turbulent ongoings with the Earls of Warwick and their possession of the manor house. In 1397, Thomas de Beauchamp, 12th Earl of Warwick, was punished by King Richard II for being a member of the Lords Appellant. All his possessions were confiscated, including the land at Sutton, which was transferred to Thomas Holland, 3rd Earl of Kent. Upon King Richard II's death in 1400, Thomas de Beauchamp was returned his possessions, although he died the following year. In 1446, Henry de Beauchamp, 14th Earl of Warwick, died and the earldom was passed to his two-year-old daughter Anne; however, King Henry VI collected the profits of the land whilst Anne was in her infancy. Anne died in 1448, and the estate and earldom passed to her aunt Anne Neville, although this was contested by her three older half-sisters. In his Itinerary, John Leland mentions that Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick, and his wife, Anne Neville, are believed to have built a new manor of timber-frame construction, with a lease given by King Henry VI in 1460 to Edward Mountfort, suggesting that the manor was then occupied by the Mountfort family.[20]

Despite being occupied by Mountfort family, Richard Neville regained his power and land, but died in 1471. Normally, the land would have remained in the possession of his wife, but instead they were given to his two daughters and their husbands. However, the eldest daughter, Isabella, contested and obtained the remainder of the interests from her sister. Isabella died in 1476, leaving the manor in the possession of her husband, George Plantagenet, 1st Duke of Clarence. However, in 1478, he was attainted and executed, meaning that the manor was passed to his only surviving son, Edward Plantagenet, who was still an infant. The Crown held the lands due to Edward's age, but in 1487 granted the lands back to Anne Neville, 16th Countess of Warwick, since both of her daughters were now dead. She immediately gave the lands back; however, Sutton and other manors were given back to her in 1489. She died in 1492, with all the land returning to the possession of the Crown, with whom it remained until it was incorporated in 1528.[20]

Growth and military influence

[edit]The manor of Sutton was not the only manor house within Sutton, as the manor of Langley was noted as being in the possession of the de Bereford family of Wishaw as early as the mid-13th century. New Hall Manor is said to date to the 13th century also, and was mentioned in 1327 as being passed from William de Sutton to Robert de Sutton. It is believed to have originally been a hunting lodge. In 1281, Peddimore Hall was first mentioned when it was sold to Hugh de Vienna by Thomas de Arden. It is presumed that the land was given to the Arden family by one of the Earls of Warwick.[20]

It is not known exactly when the village of Sutton began to develop but in 1300, Guy de Beauchamp, 10th Earl of Warwick, was granted a charter by King Edward I to hold a market on each Tuesday and an annual fair on the eve of Holy Trinity in the village. Sutton did not establish itself as a market town like Birmingham was able to, and the market appears to have fallen out of use, as a new charter was later granted to Thomas de Beauchamp, 11th Earl of Warwick, for a market to be held on the same day, as well as fairs on the eve of Holy Trinity and the eve of St. Martin.[20]

During the 12th and 13th centuries, religious activities were carried out at the free chapel of Saint Blaise, constructed within the Sutton manor grounds. In the late 1200s, the town constructed its own parish church, the first incumbent of which was ordained in 1305. This later became Holy Trinity Church, and the only remaining features of the original church survive below the east window, where clasping buttresses are visible, a method of construction from the mid-13th century.[22]

Throughout the 15th century, Sutton Coldfield developed a military connection, due in part to Sir Ralph Bracebridge who obtained a lease for his lifetime from the Earl of Warwick for the Manor and Chase of Sutton Coldfield. In return, Bracebridge was required to assist the Earl with nine lances fournies and seventeen archers in strengthening Calais from French attack.[23] As a result, Sutton Coldfield became an important training location for English soldiers during the wars between England and France. Butts were assembled within the town for archery training, and marks can still be seen in the sandstone wall on 3 Coleshill Street where archers sharpened their arrows. It is believed that 3 Coleshill Street is of medieval origin despite having a Georgian façade. Bracebridge is remembered as having dammed Ebrook to form Bracebridge Pool, now in Sutton Park, which he used for fishing.[24]

Tudor Sutton Coldfield, c. 1500–1598

[edit]Influence of Bishop Vesey

[edit]By the beginning of the 16th century, the town of Sutton Coldfield had started to decay as a result of the War of the Roses. The markets had been abandoned and the manor house itself was becoming dilapidated. Around 1510, the manor house was demolished by an officer to the Crown, who sold the timbers for a profit to Thomas Grey, 2nd Marquess of Dorset, who used them in the construction of Bradgate House in Leicestershire.[25] It was during the period of decay that John Harman grew up, working at Moor Hall Farm in Sutton and then studying at Magdalen College, Oxford. He formed a friendship with Thomas Wolsey and started a career in the church, beginning with his appointment as chaplain at the free chapel of St. Blaize in his hometown in 1495.[26] Harman continued to be promoted and became Chaplain to King Henry VIII, with whom he became friends. In 1519, Harman was appointed Bishop of Exeter and changed his surname to Vesey, thus becoming John Vesey.

It was Vesey's respected position within the church and his friendship with the King that set about the start of a revival for Sutton Coldfield, spearheaded by Vesey. He had returned to the town in 1524 for the funeral of his mother to discover the town had further deteriorated. He decided to set up residence in the town again and in 1527 obtained two enclosures of land named Moor Yards and Heath Crofts, as well as 40 acres (160,000 m2) of land for him to construct his own home named Moor Hall. In the same year, he established a grammar school in the southwest corner of the parish churchyard, where 21 people were appointed Trustees to maintain the building and employ a teacher. On 16 December 1528, through the interests of Vesey, Henry VIII granted Sutton Coldfield a Charter of Incorporation, creating a new form of government for the town which was named the Warden and Society of the Royal Town of Sutton Coldfield.[20] The society consisted of 25 of the most prominent local inhabitants who elected a new Warden from within them. Vesey's brother-in-law, William Gibbons, became the first Warden.[20] All the town's inhabitants over the age of 22 were permitted to elect members to the Society.[27] The charter had also given the inhabitants permission to hunt and fish freely in the manor grounds, as well as build a house, enclosing up to 60 acres (24 ha), within the manor grounds.[20] Throughout the length of the Society's existence, it was dogged by claims of corruption and malpractice from the town's residents.[20]

The donation by King Henry VIII of his hunting land to the residents of the town set the foundations for the preservation of the area now known as Sutton Park. Vesey cleared large tracts of the land of trees to allow residents to graze their cattle there for a small fee. He then enclosed wooded areas within the land, added gates and fencing around the park, and then arranged for the transfer of horses to the park at his own expense. Bishop Vesey also paid for the whole town to be paved, which in turn helped revive the markets. In 1527, he set about working on Holy Trinity Church, donating an organ in 1530 and then paying for the construction of two new aisles in 1533. In 1540, he approved the transfer of control of the grammar school to the Warden and Society, and gave the school land for its own use the following year. To help expand the town and protect its extremities, he constructed 51 cottages for the poor, including one at Cotty's Moor which was a hotspot for robberies of people using the roads. The stone walls of the former manor house were removed to assist in the construction of a bridge at Water Orton and another in Curdworth, at his own expense. In 1547, he purchased from the Bishop of Coventry and Lichfield, and in 1549, from the Crown, numerous church properties including the chantry lands of Sutton Coldfield, and those in Deritend, Birmingham, before dying at Moor Hall in 1555.[26] Vesey's legacy is clearly visible today, with Sutton Park largely unchanged since its enclosure, some stone cottages remaining, and the grammar school he established still operating under the name of Bishop Vesey's Grammar School. His tomb at Holy Trinity Church is accompanied by memorial gardens to the west of the church named Vesey Gardens.

Moor Hall, Bishop Vesey's residence, was inherited by his nephew John Harman after Vesey's death. He sold the mansion to John Richardson, who died in 1584, leaving an infant son.[20] A manor by the name of Pool Hall is first mentioned as being in the town in 1581, and in the following year, William Charnells leased it for 20 years to Henry Goodere, who transferred the rights to John Aylmer, Bishop of London, in 1583. Upon the Aylmer's death in 1594, the manor was passed on to his sons, who sold it to Robert Burdett in 1598.[20] It is believed that the properties at 62 and 64 Birmingham Road were constructed around 1530, making it one of the oldest surviving buildings in the town.[28] Nearby 68 Birmingham Road dates to the end of the 1500s.[29]

Emergence of industry

[edit]During the 16th century, the waters and pools within Sutton were exploited for industrial purposes and, following the death of Vesey, the town continued to prosper and expand. In 1510, two watermills under the ownership of William Weston were recorded, and upon the establishment of the park, he was forced to pay rent on them. Three other mills were recorded in 1576 after they were sold to two unnamed local men. In 1585, John Bull sold a water-fulling mill and two blade-mills, which would have been powered by water, to Edward Sprott. Four additional mills were recorded in 1588, and another two in 1595.[20] A blade mill was constructed at Bracebridge Pool in 1597, on a site now occupied by Park House.[15] Despite the growth of industry here, five pools in total were drained in the 16th century, although some were recreated later, including Bracebridge Pool and Keeper's Pool.[20]

17th and 18th centuries

[edit]Civil war, unrest and governance

[edit]The outbreak of the English Civil War in 1642 saw the Battle of Camp Hill at nearby Birmingham, which resulted in Birmingham being pillaged by Royalist forces. Despite the nearby action, Sutton Coldfield emerged unscathed, although it is known that it was visited by both Parliamentary and Royalist soldiers.[30] It is claimed that during his escape from England in 1646, Charles II stayed for a night at New Hall Manor.[31]

On 26 July 1664, King Charles II renewed the royal charter for Sutton Coldfield, with the additional provision being made for the appointment of two members of the Society as capital burgesses and also as justices of the peace alongside the Warden.[20][32]

Following his trial and three-year suspension from preaching, the violently anti-Presbyterian Henry Sacheverell retired to New Hall, the home of his once-removed first cousin, George Sacheverell.[33] Henry Sacheverell preached a vitriolic sermon at Sutton Church on Sunday 17 October 1714, which fuelled Birmingham's contribution to the nationwide rioting the following Wednesday, the day of King George I's coronation. It also appears that, whilst residing in New Hall, he helped ferment the anti-Presbyterian "Church in danger" riots of July 1715, when, according to a correspondent of George Berkeley, up to 4000 rioters gathered in Birmingham, twenty-eight rioters died, and no more than three Dissenters’ meeting-houses survived in Birmingham, Worcestershire and Staffordshire.[34] The town became a temporary refuge in 1791, following the "Priestley Riots" in Birmingham. William Hutton, for example, whose house was attacked by protesters, decided to spend the summer in Sutton. However, local residents' fears of further rioting forced him to move permanently to Tamworth.[35] Joseph Priestley is said to have stayed at the 'Three Tuns' following the destruction of his home in the riots, and his initial flight to Heath-forge, Wombourne.[21]

Industrial growth

[edit]The manufacture of blades, gun barrels, spades, and spade handles, as well as the grinding of knives, bayonets, and axes, mainly at mills constructed at pools in Sutton Park and on the banks of Ebrook, became an important contributor to the town's economy in the 17th century. The blade mill at Bracebridge Pool fell out of use by 1678 and was destroyed; however, it was reconstructed by 1729.[15] The creation of Longmoor Pool, caused by the damming of Longmoor Brook in Longmoor Valley, was approved in 1733 and carried about by John Riland, who built a mill there in 1754 with his co-tenant[20] for the manufacture of buttons.[36] Blackroot Pool was also constructed in around 1757 by Edward Homer and Joseph Duncomb. In 1772, the Warden and Society of the town gave a lease of 30 years to Thomas Ingram at the pool.[20] The mill at Blackroot Pool was originally used for leather dressing, although later became a sawmill.[36]

Powell's Pool was created in 1730 as a millpond for Powell's Pool Mill, a steel-rolling mill.[37] In 1733, a cotton-spinning machine was tested at the mill by John Wyatt with the help of Lewis Paul, helping to kickstart the creation of the UK's cotton industry in the 18th century.[38] In total, Sutton Coldfield has had 15 watermills, 13 of which were powered by Plants Brook, and the remaining two using an independent water supply. There were also two windmills in the town, at Maney Hill and at Langley.[38]

A heavy storm caused the collapse of the dam holding back the waters of Wyndley Pool,[39] which swept downstream and broke the banks of Mill Pool at Mill Street in July 1668, subsequently flooding and destroying many homes within Sutton Coldfield.[33] Bracebridge Pool also broke its banks as a result of the storm on 24 July, causing lesser damage. Wyndley Pool was subsequently drained, although there is another pool within Sutton Park with the same name.[21]

Much of the damming in Sutton Coldfield was carried out using stone and gravel quarried from within the town. These quarries also supplied stone for construction elsewhere in the town, proving to be particularly profitable. The quarry that supplied material for the construction of Blackroot Pool in 1759 was in use until 1914.[15]

Financial prosperity and town growth

[edit]During the 17th and 18th centuries, the town prospered from the growth of industry and this led to improvements in the quality of life for the residents. They were now able to experience new luxuries such as seafood. Products were 10% more expensive in Sutton Coldfield than in neighbouring towns and villages. The town also grew, due in part to the wealthy industrialists of Birmingham seeing Sutton Coldfield as a suitable location for their country houses, away from the pollution of the larger town.[40] A survey of the parish in 1630 reported that there were 298 houses, and this number had increased to 310 when another survey was conducted in 1698.[41] Of these houses would have been 20 High Street, which was built around 1675.[42] A survey of the parish in 1721 noted that the number of houses in Sutton Coldfield had increased to 360.[41] In 1636, King Charles I imposed the ship money tax of £80 on the town, compared to £100 for Birmingham and Warwick, £266 for Coventry, and £50 for Stafford, reflecting the wealth of the town at the time.[43] In 1663, an Act was passed to order and collect "Hearth Duty", which led to a subsequent survey of all houses in the country and the noting of all properties with hearths and stoves. The survey of Sutton Coldfield found that there were 67 hearths and stoves, of which 30 were attributed to two houses owned by the Willoughby family.[44]

Some of Sutton Coldfield's most prominent buildings were constructed or underwent changes during this time. For example, the current Peddimore Hall was constructed in 1659 by William Wood to a design by William Wilson, who took up residence in the town and married the widowed landowner, Jane Pudsey, in 1681.[45] Her daughters disapproved of the relationship and she was forced out of her home at Langley Hall, resulting in Wilson constructing Moat House for the couple in 1680.[46] Another of his works in the town was Four Oaks Hall, designed for Henry Folliott, 1st Baron Folliott, who was the husband of Wilson's stepdaughter. Along with the hall, Lord Folliott enclosed 60 acres (24 ha) of woodland.[47]

In 1610, New Hall Manor was purchased by Henry Sacheverell, the family of which were prominent landowners throughout the country. Upon his death in 1620, the hall was inherited first by Valence Sacheverell, and then by George Sacheverell, his eldest son.[20] Notable buildings that were constructed in the town during the 18th century include the Royal Hotel on High Street, which dates to circa 1750.[21][48] The 'Three Tuns' public house, also on High Street, dates to the late 18th century, although it retains the cellars and foundations of an earlier building.[49]

Industrial revolution, 1800–1900

[edit]Municipal projects and change of government

[edit]The 1800s would prove to be another century of major change for the town, built upon the wealth it had generated in years before and the power that the Sutton Coldfield Corporation had. Dealing with a growing town, they sought to improve the quality of life for residents. The corporation was forced to fell trees within the town and sell the timber as means to fund the construction of schools and almshouses. In 1826, timber worth £1,116 3s. was sold.[20] The first of these schools were founded during the 1820s. The corporation also constructed two almshouses in Walmley in 1828 and a further two adjacent in 1863.[50] By 1837, there were ten almshouses in the parish under the ownership of the corporation, with others operated by charities.[51]

The town hall at the top of Mill Street began to deteriorate throughout the 1800s and the decision was taken to demolish it in 1854. The adjacent workhouse and gaol were renovated to become the new municipal offices, and this was reconstructed in 1858 until 1859 to better suit its purpose. The new offices were designed by G. Bidlake.[52] A fire station was also constructed further down Mill Street.[52]

During the 1830s, municipal corporations were investigated due to corrupt practices within the House of Commons. These inquiries led to the passing of the Reform Act of 1832 and Municipal Corporations Act of 1835 which reformed boroughs nationwide. Despite the radical changes imposed by the Acts, the Sutton Coldfield Corporation was left untouched.[40] It was not until April 1882, as a result of the Municipal Corporations Act of 1882, that Sutton Coldfield became a municipal borough. The old Corporation was replaced with a new structure consisting of a mayor, six aldermen and eighteen elected councillors. Six wards were created in the borough – Holy Trinity, Hill, Boldmere, Wylde Green, Maney, and Walmley – from each of which three councillors were elected.[20]

Arrival of the railways

[edit]For the majority of the 19th century, people travelled between Birmingham and Sutton Coldfield by horse-drawn carriage, a journey that took around 80 minutes.[52] Birmingham received its first railway in 1837 with a terminus at Vauxhall station, now Duddeston railway station. In 1859, an Act was passed for the construction of a railway line connecting Birmingham to Sutton Coldfield via Erdington.[53] Construction commenced in 1860 on the line which passed through Vauxhall station, although by this time it was being used only as a goods station. The line opened on 2 June 1862 with Sutton Coldfield railway station being the terminus. An Act of Parliament for the continuation of the railway to Lichfield was passed on 23 June 1874, with construction starting in October 1881[44] and services beginning in 1884.[54] The line was extended to Lichfield Trent Valley railway station on 28 November 1888.[55]

A proposed second railway line by the Wolverhampton, Walsall and Midland Junction Railway Company through Sutton Coldfield was met with opposition from residents who were concerned about the route cutting through Sutton Park. A meeting objecting to the proposal was held on 15 April 1872,[44] however, construction was authorised on 6 August in the same year. The WWMJR company merged with Midland Railway in 1874 and construction commenced soon after. To calm objections from residents, Midland Railway promised cheap local coal and paid £6,500 for a 2-mile (3.2 km) stretch through Sutton Park.[56] Services on the line began on 1 July 1879, with trains stopping at Penns (Walmley), Sutton Coldfield Town, and Sutton Park in the town, as well as at Streetly, Aldridge, and Walsall. Ultimately, the line connected the Midland Railway's Wolverhampton and Walsall Railway line to their Birmingham to Derby line.[56]

The railways quickly led to Sutton Coldfield becoming a popular location for day excursions and picnic parties for the residents of Birmingham, escaping the pollution of the city for the landscapes of Sutton Park.[57] The 1863 edition of Bradshaw's Guide described Sutton Coldfield as "a place of no very particular note, beyond an occasional pic-nic excursion".[58] In the Whit week of 1882, 19,549 people visited Sutton Park, with numbers dropping to 11,378 in the same week the following year. In 1884, there were 17,486 visitors, of whom 14,000 went on the Monday.[44] In 1865, on a small eminence adjacent to Sutton Coldfield station, the Royal Hotel was constructed, hoping to capitalise on the new tourist industry the town was witnessing. The hotel was beset with financial difficulties and closed down in 1895, becoming Sutton Coldfield Sanatorium for a short period of time.[47]

As well as becoming a tourist spot, Sutton Coldfield became popular with people who worked in Birmingham and also were able to live away from the pollution of the city and travel to the city and town by train.[59] During the late 19th century, it was the wealthy manufacturers who moved to Sutton Coldfield, and it was not until the turn of the century that ordinary workers were able to move as well.[40]

In 1836, George Bodington acquired an asylum and sanatorium at Driffold House (now the Royal cinema), Maney, where he researched pulmonary disease.

Population growth and public facilities

[edit]The first census of Sutton Coldfield took place in 1801. It recorded that the town had a population of 2,847. The following census of 1811 recorded that this had risen to 2,959 with 617 houses. This was partially down to the construction of barracks to the east to accommodate the Edinburgh and Sussex Militias, the 7th Dragoon Guards and a Brigade of Artillery. By 1821, the population had further increased to 3,426[60] and then to 3,684 in 1831.[20] The census of 1881 revealed that the population had increased from 4,662 in 1861[61] to 7,737.

The increasing population of Sutton Coldfield parish was recognised in the mid-19th century and new ecclesiastical parishes were created from it to better serve the residents of the communities that made up Sutton. The first ecclesiastical parish to be created was Walmley in 1846, with the recently completed St. John the Evangelist Church becoming the parish church.[62] Hill became the next ecclesiastical parish in 1853, with its church being St. James' Church in Mere Green.[63] Boldmere parish was created in 1857, with St. Michael's Church becoming its parish church.[64] Holy Trinity Church was further extended with a north outer aisle and vestries in 1874–9.[20]

The construction of Shenstone Pumping Station in 1892 gave Sutton Coldfield its first tapped water supply.[65] In 1870, W.T. Parsons began the publication of Sutton Coldfield's first newspaper Sutton Coldfield News.[66]

Ashford v Thornton

[edit]Sutton Coldfield was the focus of national attention in 1817 when a young woman named Mary Ashford was found murdered in the town. She had been attending a party in Erdington on the evening of 26 May 1817,[67] and had left with Abraham Thornton and her friend Hannah Cox, who left Mary and Abraham.[68] The following morning, her body was recovered from a water-filled pit by Penns Lane, Erdington. Thornton was quickly traced and arrested for her murder.[69] At the trial, Thornton provided evidence that it was not possible for him to have killed Mary at the suggested time.[70] As a result, the jury found him not guilty of her murder and rape, allowing him to walk free from the court.[71]

Public response to the acquittal was that of outrage and a private appeal was brought against the verdict by Mary's brother, William Ashford.[72] Thornton was taken to London where he was tried at the King's Bench.[73] When Thornton was called upon for his plea, he responded, "Not guilty; and I am ready to defend the same with my body."[74] He then put on one of a pair of leather gauntlets, which his barrister, William Reader, handed him. Thornton threw down the other for William Ashford to pick up and thus accept the challenge, which Ashford did not do. By Ashford not accepting the challenge under the trial by combat laws, Thornton was freed, although by this time he gained a notorious reputation.[75] In 1819, a bill was introduced and an Act passed to abolish private appeals after acquittals and also abolish trial by combat.

20th century

[edit]In the 20th century, Sutton Coldfield continued to grow. The areas on the fringes of the district remained rural up until the end of World War I. As witnessed nationally, there was a house construction boom in areas such as Boldmere, Walmley, Erdington and Four Oaks. Again, the population increased rapidly. During World War II, Sutton Park and areas of Walmley were used as prisoner-of-war camps, housing German and Italian prisoners. After the war, Sutton witnessed a major redevelopment. The Borough Council commissioned Max Lock and Partners to draw up plans for the redevelopment of the town centre in 1960, with a preliminary report being delivered in May 1961 and a detailed report in 1962.[76] The Parade in the town centre was almost completely demolished for the construction of a large new shopping centre named Gracechurch. In addition, shopping centres in Wylde Green and Mere Green were constructed causing considerable objection as many local landmarks were lost to the developers.

Merging into Birmingham

[edit]In 1974, Sutton Coldfield became part of Birmingham when the metropolitan county of the West Midlands was formed. More recently, areas of the town centre have been pedestrianised.

Plans for the proposed construction of five tower blocks for pensioners at Brassington Avenue in the town centre were abandoned in November 2015.[77]

On 1 March 2015, a new Sutton Coldfield parish council was formally incorporated. This handed over parish council powers from Birmingham City Council.

Governance

[edit]

In 1528, a charter of King Henry VIII gave the town the right to be known as "The Royal Town of Sutton Coldfield" and to be governed by a warden and society. The charter was secured by Bishop John Vesey. This unreformed corporation survived until 1885, when it was replaced by a municipal borough. Although the title "Royal Town" was still used, the municipality created in 1885 was not itself a Royal borough. However, the townspeople sometimes still use its historic 'Royal' title. This was confirmed to be allowed in 2014 after a two-year campaign by a local newspaper, the Sutton Coldfield Observer, Andrew Mitchell MP, the Sutton Coldfield Civic Society and various local residents. On Thursday, 12 June 2014 government minister Greg Clark confirmed during a special adjournment debate in the House of Commons that "there is no statutory ban to the continuance of historic titles for other [non-governance] purposes" in the absence of a local governing structure using a historic name, and thus the use of the Royal title is not prohibited (although any such usage has a "lack of technical legal effect").[3][4] Following that confirmation, the newspaper renamed itself the Royal Sutton Coldfield Observer.

The town and borough were ceremonially part of Warwickshire until 1974, when it was amalgamated into the City of Birmingham and the metropolitan county of the West Midlands. The formal Mayoral chains of office are now on display in Birmingham Council House.

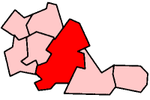

Sutton Coldfield forms the Sutton Coldfield parliamentary constituency, the largest Parliamentary Constituency in Birmingham whose member of parliament (MP) since 2001 has been Andrew Mitchell (Conservative). Within the City of Birmingham metropolitan borough, it comprises the wards of Sutton Four Oaks, Sutton Mere Green, Sutton New Hall, Sutton Reddicap, Sutton Roughly, Sutton Trinity, Sutton Vesey, Sutton Walmley & Minworth, and Sutton Wylde Green. The ward of Erdington ceased to be part of the constituency in 1974 due to the Local Government Act of 1972. Sutton Trinity ward was created in June 2004, at which time the then other three wards' boundaries were changed. From 5 April 2004, it has been a council constituency, with many local services managed by a district committee made up of all Sutton's councillors.

In 2015 the eligible electorate within the Royal town's boundary were asked whether they wished to be governed by an independent Town council. The result of the election was that almost 70% were in favour of a Sutton Coldfield Town Council. Work is now ongoing in the Birmingham City Council to create a new council and decide which powers to transfer.[78] The first parish council election took place on 5 May 2016.[79]

Geography

[edit]Areas of Sutton Coldfield include:

- Boldmere

- Doe Bank

- Falcon Lodge

- Four Oaks

- Four Oaks Park

- Hill Hook

- Ley Hill

- Maney

- Mere Green

- Minworth

- Moor Hall

- Reddicap Heath

- Roughley

- Streetly

- Thimble End

- Tudor Hill

- Walmley

- Whitehouse Common

- Wylde Green

Sutton Coldfield borders the counties of Staffordshire and Warwickshire as well as the Metropolitan Borough of Sandwell, Metropolitan Borough of Solihull and Metropolitan Borough of Walsall. The town in general is regarded by its own populace as one of the most prestigious locations in the Birmingham area and even in Central England; a 2007 report by the website Mouseprice.com placed two Sutton Coldfield streets amongst the 20 most expensive in the United Kingdom.[80][81][82]

The northern stretch of the Birmingham city sandstone ridge culminates at Sutton Coldfield. Plants Brook rises in the area of Streetly and flows through Sutton Park and directly beneath the town centre, then Plants Brook briefly flows through Erdington, notably Pype Hayes Park before returning to Sutton and culminating at Plantsbrook Nature Reserve on the Erdington / Walmley border at Eachelhurst Road.

Retail

[edit]The main shopping centre is the Gracechurch Centre, built in 1974. For a number of years this centre was called The Mall. The complex includes a multi-storey car park. As a result of investment, the appearance of the shopping centre was improved in 2006, which included the installation of a glass roof above one of the walkways and the removal of a public square to form a cafe and extra retail units. The shopping centre was formerly home to three bronze sculptures that depict, respectively, a boy and a girl on rollerskates, a boy with a dog, and a boy and a girl playing leapfrog, which have been moved to Rectory Park.[83]

A second shopping centre was named the Sainsbury Centre until Sainsbury's closed their store;[84] the name was later changed to "The Red Rose Centre". The centre has its own multi-storey car park (now disused) with access from Victoria Road.

Sutton Parade is a continuation of Birmingham Road and Lichfield Road (though there is a bypass for traffic). New Hall Walk is a row of shops built behind The Parade in the late 1990s. The company that manages the site also manages several of the shops on the Parade built at the same time. It has its own large outdoor car park. Opposite the Red Rose Centre, behind New Hall Walk, is a single floor, indoor market facility known as the In Shops.[citation needed]

There are several local shopping parades serving the suburbs of Sutton, including "The Lanes" Shopping Centre in Wylde Green, at Walmley, and at Boldmere Road.

Sport

[edit]Sutton Coldfield Town F.C. is a football club that was founded in 1879 and play at Coles Lane.[85] Paget Rangers F.C. are another club that share the ground at Coles Lane.[86]

Sutton Coldfield is home to numerous golf clubs and courses, such as Sutton Coldfield Golf Club, Walmley Golf Club, Pype Hayes Golf Course, Aston Wood Golf Club, Moor Hall Golf Club, Little Aston Golf Club and Boldmere Golf Club.[87][88][89][90][91][92] Nearby is The Belfry, a hotel with a renowned golf complex whose Brabazon course has hosted the Ryder Cup several times.

A number of local cricket clubs play in the Sutton Coldfield area, such as Walmley, Sutton Coldfield and Four Oak Saints.[93][94][95]

Sutton Coldfield Hockey Club is a field hockey club that competes in the Women's England Hockey League and the Midlands Hockey League.[96][97] In the area is also Beacon Hockey Club (formerly Aldridge and Walsall Hockey Club) and Alliance International Hockey Club.[98][99][100]

Sports facilities, including swimming pool and 400m athletics track, are located at Wyndley Leisure Centre, on the edge of Sutton Park. This was opened in 1971 by Ethel E. Dunnett. The nearby youth centre was opened in September 1968. Parts of Rectory Park is leased to Sutton Coldfield Hockey Club, Sutton Coldfield Cricket Club and Sutton Town Football Club.

In 2022 Sutton Coldfield hosted the Triathlon for the 2022 Commonwealth Games, which took place in Sutton Park.

There is a fencing club, Sutton Coldfield Fencing Club.[101]

Places of interest

[edit]

Parkland

[edit]Sutton Park, with an area of 2,224.2 acres (9.001 km2), is one of the largest urban parks in England. It is used as part of the course for the Great Midlands Fun Run. The park is a national nature reserve and a Site of Special Scientific Interest.

New Hall Valley, which separates Walmley and Maney, is the location of New Hall Valley Country Park which was opened formally on 29 August 2005. It has an area of 160 acres (0.65 km2) and within it is New Hall Mill, one of only two working watermills in the West Midlands. The mill is privately owned but is open to the public several times a year.

There are also several nature reserves including Plants Brook Nature Reserve, in Walmley, and Hill Hook Nature Reserve. On the border between Sutton Coldfield and Erdington is the extensive Pype Hayes Park and adjacent golf course, with the park falling within Tyburn ward but the golf course in Sutton New Hall.

Historic houses

[edit]Sutton Coldfield has been an affluent area in the past leading to the construction of manors and other large houses. Several have been renovated into hotels such as the New Hall Hotel, Moor Hall Hotel, Moxhull Hall Hotel, and Ramada Hotel and Resort Penns Hall. Peddimore Hall, a Scheduled Ancient Monument near Walmley, is a double-moated hall used as a private residence. Demolished manor houses include Langley Hall, the former residence of William Wilson and Four Oaks Hall, designed by William Wilson. William Wilson is also known to have designed Moat House and lived in it with his wife, Jane Pudsey. It is Grade II* listed.[102]

Conservation areas

[edit]

There are two conservation areas in Sutton Coldfield. The High Street, King Edward's Square, Upper Clifton Road, Mill Street, and the northern end of Coleshill Street are protected by the High Street conservation area, which is part covered by an Article 4 Direction. At the centre of the conservation area is Holy Trinity Church, which is fronted by the Vesey Memorial Gardens, created in memory of Bishop John Vesey. The High Street conservation area was designated on 28 November 1973 and extended on 6 February 1975, 14 August 1980 and again on 16 July 1992. It covers an area of 0.1695 square kilometres (41.87 acres).[103]

Beyond the railway bridge, which crosses the Sutton Park Line and separates the Lichfield Road and High Street, is the Anchorage Road conservation area which protects buildings such as Moat House by William Wilson. The conservation area was designated on 15 October 1992 and covers an area of 0.1757 square kilometres (43.41 acres).[104]

Religious buildings

[edit]

Holy Trinity Church is one of the oldest churches in the town, having been established around 1300. The church has been expanded over time, notably by John Vesey, Bishop of Exeter who built two aisles and added an organ.[105] His tomb is located within the church.[106] Outside of Sutton town centre, there are numerous other churches, many of which are listed buildings.

In Four Oaks is the Church of All Saints which is a Grade B locally listed building. It was built in 1908 and designed by Charles Bateman, whose Arts and Crafts are seen in the building.[107] Another church in Four Oaks which is of a mixed Arts and Crafts-Gothic style is Four Oaks Methodist Church, built between 1907 and 1908 to a design by Crouch and Butler. It is Grade II listed.[108] The Methodist Hall attached to it is also Grade II listed.[109]

In Mere Green is the Church of St Peter, also by Charles Bateman, which was built between 1906 and 1908. The building is Grade II listed.[110] Also designed by Charles Bateman is the Church of St Chad near Walmley. This was built between 1925 and 1927. The side chapel was built in 1977 to a design by Erie Marriner. It is Grade II listed.[111] St Johns Church, built in 1845 to a design by D. R. Hill, is located on the Walmley Road in Walmley. It is the parish church for Walmley and is of a Norman architectural style. It is Grade C locally listed.[112]

In Maney, near Walmley, is St Peter's Church which began construction in 1905, although the tower, which was designed by Cossins, Peacock and Bewley, was constructed in 1935 and the building is Grade II listed.[113] Located on the border of Sutton town centre is Church Hall, a former Roman Catholic Chapel, built around 1834. The building is now used for offices and is Grade II listed.[114]

In Wylde Green, on Penns Lane is The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Wylde Green Ward. The chapel on Penns Lane was constructed in the early 1990’s. The England Birmingham Mission Headquarters have been located there since 1964, the mission office building is made of Cotswold stone.[115] The site on Penns Lane will be the location of the Birmingham England Temple, the third temple to built in the United Kingdom by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

The Green Belt

[edit]Birmingham has 4,153 hectares of Green Belt, about 15% of the city's land area. The majority of this is in the north of the city, particularly to the north and east of Sutton Coldfield.[116] The current Green Belt within Birmingham was initially installed in place in 1955 and was last reviewed around 20 years ago, since then the boundaries have remained unchanged.

Sutton Coldfield's Green Belt is being extensively developed with over 5500 houses to be built and a large industrial complex currently under construction. The Langley Sustainable Urban Extension (SUE) and the 71 hectare Peddimore site have been approved and will destroy much of the Green Belt.[117]

Public facilities

[edit]The Town Hall, a relic of Sutton Coldfield's former status as a municipal borough, now serves as a theatre, conference, and function venue.

In the town centre is Sutton Parade which is a pedestrianised shopping area. Sutton Coldfield Library, which opened in 1974, is located near Sutton Parade above the Red Rose Centre. It also contains the Sutton Coldfield Reference Library, which holds a large collection of newspapers and magazines with all Sutton Coldfield based publications such as Sutton Coldfield News and Sutton Coldfield Observer being held permanently.[118] The Library closed in May 2010 due to the discovery of disturbed asbestos and reopened in May 2013. There are several branch libraries in Sutton Coldfield and there is also a bus service from Sutton Parade to Birmingham City Centre and Birmingham Central Library, The Central Library and the terminus of busses from Sutton Coldfield are both within the City Centre Core and in walking distance of each other.

Also in the Town centre is Sutton Coldfield railway station, which is part of the Birmingham Cross-City Line. Nearby is the Town Gate entrance to Sutton Park and the Sutton Park Visitor's Centre.

Sutton Coldfield has four Community Centres and a number of smaller Community Halls all offering classes and events in a wide variety of subjects and interests –

- Mere Green Community Centre

- Falcon Lodge Community Centre

- Banners Gate Community Hall

- Brampton Hall Community Centre

Good Hope Hospital provides main hospital services to the town, including accident and emergency facilities. Another hospital in Sutton Coldfield is Sutton Cottage Hospital, which is operated by the Birmingham East and North Primary Care Trust.[119] It opened in 1908 and the buildings were designed by Herbert Tudor Buckland and Edward Haywood-Farmer.[120]

On Lichfield Road, Sutton Coldfield is served by a police station, magistrates' court (both opened in 1960, the court now closed) and fire station (opened 1963). On the opposite side of the road is Sutton Coldfield College, which is the main college of further education for the area. Also located on the north-eastern outskirts of the area is Sutton Coldfield transmitting station, the first television transmitter to broadcast outside the London area.

Transport

[edit]

Linked by frequent and fast services from Sutton Coldfield railway station on the Cross-City Line to the centre of Birmingham, Sutton is mostly a commuter dormitory town for people who work in Birmingham. The 1955 Sutton Coldfield rail crash occurred here, when an express train entered the very tight curve through the station much faster than the speed limit of 30 mph (48 km/h). The Sutton Park Line also crosses the town roughly perpendicular to the cross-city line (crossing at a point out of easy sight near the former Midland Road station), but lost its passenger services and stations in the 1964 "Beeching Axe". It retained a loading bay at the adjacent Clifton Road Royal Mail sorting office for a time, but now remains as a freight only line.

The Roman road Icknield Street cuts through Sutton Park to the west of the town. The town is bypassed to the north by the M6 Toll, the first toll motorway in the UK, accessible from Sutton by junction T2 at Minworth (co-located with the M42 junction), T3 and T4 (interchanging with the A38 at the south and north ends of their 5-mile (8.0 km) parallel run), and T5 at Shenstone. It also has easy access to the M6 to the South, via junctions 5 (Castle Bromwich), J6 (Gravelly Hill, or "Spaghetti Junction") and J7 at Great Barr; and also the M42 in the east, via junction 9 near Minworth.

The A38 itself used to run through the centre of the town (literally, using the since-pedestrianised line of the Parade), but now uses the dual carriageway bypass to the east. The former route of the A38 is now the A5127 Lichfield Road, branching from the southern end of the Aston Expressway on the Birmingham Middleway ring road, and continues to provide a major connective route running between and on slightly altered paths through the centres of Erdington, Sutton and Lichfield.

The Parade in the town centre is the main destination and terminus for numerous National Express West Midlands bus services in and through Sutton Coldfield. Such routes as 'Sutton Lines' (X3, X4, X5, X14) to Birmingham, 77 to Walsall and 5 to West Bromwich; to name just a few routes. There is also a half-hourly service X3 to Lichfield operated by National Express West Midlands. This partially replaced service X12 to Burton-upon-Trent which was run by Midland Classic. Arriva Midlands operate service 110 up to every 15 minutes between Birmingham and Tamworth.

Sutton Coldfield TV transmitter

[edit]The nearby Sutton Coldfield transmitter is situated north of the town which provides television and radio signals to the West Midlands. [121]

Education

[edit]Fairfax Academy is on Reddicap Heath Road in the east of the town. Opposite the school is The John Willmott School. Sutton Coldfield Grammar School for Girls is on Jockey Road (A453). Bishop Vesey's Grammar School, its male equivalent, is on Lichfield Road (A5127/A453) in the centre of the town adjacent to Birmingham Metropolitan College. The Arthur Terry School is on Kittoe Road in Four Oaks in the north of the town near Butlers Lane station. The Plantsbrook School (formerly The Riland Bedford School) is on Upper Holland Road near the centre of the town in Maney. The Bishop Walsh Catholic School is next to the Sutton Park Line and New Hall Valley Country Park; the school is 10 minutes from Wylde Green. All these schools are for ages 11–18. However, from September 1972 until July 1992, schools in the Sutton Coldfield area were divided into first school for pupils aged 5–8 years, middle schools for pupils aged 8–12 years, while the entry age for secondary school was set at 12 years.

There are also a number of primary schools located in the town including:

- St Joseph Catholic Primary School

- Whitehouse Common Primary School

- Deanery Primary School

- Banners Gate Primary School

- Holy Cross Infant and Junior Catholic Primary School

- Walmley Primary School

- Maney Hill Primary School

- Moor Hall Primary School (in the Mere Green area)

- The Shrubbery School (established in 1930, is a private primary school located on the fringes of Walmley and Hollyfield primary located on Hollyfield Road, founded in 1907)

- Four Oaks Primary

- New Hall Primary and Children's Centre, Little Sutton, Coppice Primary, Hill West and Mere Green Combined

Highclare School, founded in 1932, is a primary and secondary school located on three sites in the Birmingham area. Two of the sites are located in Sutton Coldfield, with the other being located in nearby Erdington. The Sutton Coldfield facilities are on Lichfield Road in the Four Oaks area and in the Wylde Green area to the south, which houses the nursery.

St Nicholas Catholic Primary School in Jockey Road is a voluntary aided Catholic primary school. Established in 1967, there are currently about 210 pupils. The school is oversubscribed.[122][123]

Sutton Coldfield in literature

[edit]The town is mentioned in Shakespeare's Henry IV, Part 1, Act 4, scene 2. Falstaff, "on a public road near Coventry", who is leading a band of conscripted men on the way to what will be the Battle of Shrewsbury, tells Bardolph of his determination to march from Coventry to Sutton that evening:

- Falstaff: Bardolph, get thee before to Coventry; fill me a bottle of sack: our soldiers shall march through: we’ll to Sutton-Co’fil’ to-night.

Kitty Aldridge's 2001 novel, Pop, is based in the town during the 1970s.

Sutton Coldfield, specifically the aforementioned Sutton Park, is a pivotal location in Hekla's Children by James Brogden. Sutton Park was the site of a portal between the physical world and the spirit world of Un.[124]

The Sadness of The King George, a 2021 novel by Birmingham author Shaun Hand, is set in the town during summer 2005.[125]

Arts

[edit]Sutton Coldfield has a very active arts community with numerous local amateur dramatic groups, musical theatre companies, orchestras and dance schools. The Royal Sutton Coldfield Orchestra was founded in 1975 and regularly arrange public concerts, often featuring guest professionals. In April 2011 Birmingham City Council provided seed funding for the creation of "Made in Sutton", a local arts forum which aims to bring together local arts organisations and champion arts activity across the town.[126] Made in Sutton is coordinated by The New Streetly Youth Orchestra.[127] The Royal Sutton Coldfield Concert Orchestra (RSCCO) hold regular local concerts and is a registered charity. There are two major amateur theatres in the Sutton Coldfield area; Highbury Theatre and Sutton Arts Theatre, both have been established since the 1930s and are very popular with the residents of both Sutton and the neighbouring Boldmere district.

The members of the British hip hop group The Northern Boys are from Sutton Coldfield.[128]

Notable residents

[edit]This article's list of residents may not follow Wikipedia's verifiability policy. (October 2018) |

The notable people who were born or have lived in Sutton Coldfield include:

- Scott Adkins – actor[129]

- Barry Bannan – footballer for Sheffield Wednesday and Crystal Palace[130]

- Jim Barron – former Wolverhampton Wanderers footballer

- Louie Barry – Footballer for Aston Villa

- Lucy Benjamin - EastEnders actress who shot Phil Mitchell

- Maurice Beresford (1920–2005) – medieval archaeologist, Professor of Economic History at the University of Leeds.

- Christophe Berra – former Wolverhampton Wanderers footballer

- Slaven Bilić – manager of West Bromwich Albion

- Blakfish - mathcore band who met and formed at Plantsbrook School in 2000

- George Bodington (1799–1882) – GP and pulmonary specialist

- Mary Brancker (1914–2010) – veterinary surgeon who was the first woman to be president of the British Veterinary Association.

- Stacey Cadman – actress

- John Cannan (1954-2024) - Murderer

- Colin Charvis – Welsh international rugby union player

- Francis James Chavasse (1846–1928), born in Sutton Coldfield. This member of the Chavasse family became Bishop of Liverpool, founder of St Peter's College, Oxford, and father of Bishop Christopher Chavasse (1884–1962) and Captain Noel Chavasse, Victoria Cross recipient (1884–1917). Chavasse Road, a cul-de-sac off Ebrook Road, is named after him.

- Ciaran Clark – footballer for Newcastle United and Aston Villa

- Hazel Court (1926-2008) - actress

- Stella Creasy – Labour Member of Parliament for Walthamstow since 2010

- Derek Dauncey – World Rally Team Manager, Mitsubishi Ralliart Japan

- Cat Deeley – television presenter

- Rory Delap – footballer

- Nick Dunphy – footballer

- Doug Ellis (1924-2018)– former Aston Villa chairman

- Trevor Eve – actor

- James Fleetwood (1603–1683) – later Bishop of Worcester

- Kate Gerbeau (née Sanderson) – television presenter

- Duncan Gibbins (1952-1993) – director of films and music videos including WHAM Club Tropicana and attended The Arthur Terry School

- Noele Gordon (1919-1985)- Crossroads actress who lived on the Driffold in Maney

- Rob Halford – singer of Judas Priest

- Rasmus Hardiker – actor

- Jonathan Harvey (1939–2012) – composer

- Alan Jerrard (1897–1968) – holder of the Victoria Cross

- Ísak Bergmann Jóhannesson – Footballer for Iceland national football team

- Mike Jordan – racing driver

- Mark Kinsella - Aston Villa F.C. and Charlton Athletic F.C. Footballer, Irish National Team Captain.

- Robert Koren – former West Bromwich Albion footballer

- Anna Kumble – British pop star, better known as Lolly

- Russell Lewis – former child actor and television writer

- Arthur Lowe (1915–1982) – comic actor. Ashes scattered at Sutton Coldfield Crematorium

- Sir Michael Lyons – former chairman of the BBCTrust

- Michael Mancienne – professional footballer

- Paul Merson – footballer[131]

- Jonathan Miles (born 1986) – cricketer

- Ken Miles (1918–1966) – racing and sports car driver

- Andrew Mitchell - the town's MP since 2001. Served as Secretary of State for International Development between 2010 and 2012 but resigned after becoming caught up in the "Plebgate" scandal.

- Sir Roger Moore (1927–2017) – actor, most famous for portraying James Bond from 1973 to 1985, formerly lived in Sutton Coldfield

- Mike Nattrass – Member of the European Parliament for the West Midlands region for the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP)[132]

- Charles N'Zogbia – former footballer for Aston Villa

- Martin O'Neill – Irish footballer and former manager of Aston Villa

- Sir Alfred Owen (1909–1975) – proprietor of Rubery Owen and BRM Formula 1 racing cars

- Renato Pagliari (1940–2009) – singer famous for "Save Your Love"

- David Parker (football manager) – Football Manager & Former Manager of Birmingham City

- James and Oliver Phelps – actors, played the Weasley twins in the Harry Potter film series

- Abi Phillips – actress in the Hollyoaks TV series

- Natalie Powers – singer, member of Scooch who represent Britain at the Eurovision Song Contest 2007 with Flying the Flag (for You)

- John Shelley – illustrator

- Steve Shirley – British businesswoman and philanthropist

- Bradley Will Simpson – lead singer of The Vamps

- Jane Sixsmith – international hockey player

- Gregory Spawton – musician

- John Benjamin Stone (1838–1914) – four-time Mayor

- James Sutton – Hollyoaks actor

- Connie Talbot – child singer

- Jim Tomlinson – tenor saxophonist, clarinetist and composer

- Chandeep Uppal – actress

- Darius Vassell – footballer

- James Vaughan – Birmingham F.C. footballer

- Brigadier Rory Walker (1932–2008) – SAS Commander

- Dennis Waterman (1948-2022) – actor, Minder formerly lived in Sutton

- Arnold Horace Santo Waters (1886–1981) – holder of the Victoria Cross

- Peter Weston (1944–2017) – British science fiction fan and winner of multiple Hugo Awards

- John Willcox (born 1937) - England and British Lions rugby union player. Brother of Sheila Willcox.

- Sheila Willcox (1936-2017) - Eventer. Sister of John Willcox.

- Ashley Williams – Swansea City and Wales footballer

- Emma Willis (née Griffiths) – television presenter, former model and wife of Matt Willis from Busted

- Ann Winterton, Lady Winterton - Conservative MP for Congleton from 1983 to 2010

- Chris Woakes – England cricketer, World Cup winner 2019

- Baruch Harold Wood (1909–1989) – chess master, writer and organiser

- William F. Woodington (1806–1893) – painter and sculptor

- John Wyatt (1700–1766) – inventor and engineer

- Dorian Yates – six-time Mr. Olympia bodybuilding world champion

- Sir Anthony Zacaroli (Lord Justice Zacaroli) - Lord Justice of Appeal[133]

See also

[edit]Further reading

[edit]- The Gentleman's Magazine (Vol. XXII), page 270, Sylvanus Urban, 1790

- Sutton Coldfield, 1974–84: The Story of a Decade: a Look at Life and Events in the Royal Town, Douglas V. Jones, 1984, Westwood Press Publications (ISBN 0-948025-00-X)

- Sutton Coldfield: a history & celebration, Alison Reed; Francis Frith Collection, 2005 (ISBN 1-84589-218-6)

- Sutton Coldfield under the Earls of Warwick, Christine Smith, 2002, Acorn (ISBN 1-903263-71-9)

References

[edit]- ^ "SUTTON COLDFIELD in West Midlands (West Midlands) Built-up Area Subdivision". City Population. Retrieved 9 January 2023.

- ^ "Home". Royal Sutton Coldfield Town Council.

- ^ a b "Sutton Royal Status Confirmed". suttoncoldfieldobserver.co.uk. 12 June 2014. Archived from the original on 11 July 2014. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

- ^ a b "Sutton Coldfield's royal status is reaffirmed". BBC News. 12 June 2014.

- ^ "Sutton Park – History". Sp.scnhs.org.uk. 7 December 2012. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- ^ "The Archaeology of the M6 Toll 2000–2003". Wessex Archeology Online. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ^ a b c "M6 Toll Motorway". Birmingham City Council. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

- ^ Hodder, Mike. "Burnt mounds and beyond: the later prehistory of Birmingham and the Black Country" (doc). West Midlands Regional Research Framework for Archaeology, Seminar 2. University of Birmingham. Retrieved 13 September 2010.[dead link]

- ^ Dargue, William. "Langley, Langley Gorse, Langley Heath, Sutton Coldfield". A History of Birmingham Places & Placenames . . . from A to Y. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

- ^ Dargue, William. "Fox Hollies, Sutton Coldfield". A History of Birmingham Places & Placenames . . . from A to Y. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

- ^ a b Hutton, William (1782). The History of Birmingham. pp. 476–7.

- ^ Balsom, Bryan. "The Heritage Trail at Bourne Brook and Pool" (PDF). Wm Wheat & Son. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 March 2012. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

- ^ a b c "Sutton Park: Archaeology 1". Birmingham City Council. Archived from the original on 30 August 2011.

- ^ Chinn, Carl (2003). Birmingham: Bibliography of a City. University of Birmingham Press. p. 15. ISBN 1-902459-24-5.

- ^ a b c d e "Walking in their Footsteps" (PDF). Local History Initiative. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 June 2011. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- ^ "The Historical Valley". New Hall Valley Country Park. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

- ^ "Continuity And Discontinuity in The Landscape: Roman to Medieval in Sutton Chase" (PDF). Arts and Humanities Data Service. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

- ^ "Roman Birmingham". Birmingham City Council. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

- ^ Bracken, L. (1860). History of the forest and chase of Sutton Coldfield. Benjamin Hall. p. 10.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Salzman, L. F. (1947). "The borough of Sutton Coldfield". A History of the County of Warwick: Volume 4: Hemlingford Hundred. Republished by British History Online. pp. 230–245. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f Dargue, William. "Sutton/ Sutton Coldfield". A History of Birmingham Places & Placenames . . . from A to Y. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

- ^ "History". Holy Trinity Parish Church. Archived from the original on 18 June 2010. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

- ^ Bracken, L. (1860). History of the forest and chase of Sutton Coldfield. Benjamin Hall. pp. 45–6.

- ^ Bracken, L. (1860). History of the forest and chase of Sutton Coldfield. Benjamin Hall. p. 52.

- ^ Bracken, L. (1860). History of the forest and chase of Sutton Coldfield. Benjamin Hall. pp. 51–52.

- ^ a b Bracken, L. (1860). History of the forest and chase of Sutton Coldfield. Benjamin Hall. pp. 57–65.

- ^ Weinbaum, Martin (2010). British Borough Charters 1307–1660. Cambridge University Press. p. 118. ISBN 978-1-108-01035-1.

- ^ Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1075818)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 14 September 2010.

- ^ Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1067108)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 14 September 2010.

- ^ Amphlett, John (2009). A Short History of Clent. BiblioBazaar. p. 124. ISBN 978-1-103-20118-1.

- ^ "A History of New Hall". Handpicked Hotels. Retrieved 14 September 2010.

...it is said that Charles II stayed one night at New Hall during his flight from England...

- ^ Warden and Society of the Royal Town of Sutton Coldfield (1853). The charters of the royal town of Sutton Coldfield. Benjamin Hall. pp. 29–38.

- ^ a b Riland-Bedford, William Kirkpatrick (2009) [1889]. Three Hundred Years of a Family Living; Being a History of the Rilands of Sutton Coldfield. General Books. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-150-13395-4.

- ^ Gilmour, Ian; Riot, risings and revolution (London, 1992); ISBN 0091753309.

- ^ Hutton, William (1841). The life of William Hutton, stationer, of Birmingham, and the history of his family. Charles Knight & Co. pp. 58–59.

- ^ a b Coxhead, Peter. "The Pools of Sutton Park". Sutton Coldfield Natural History Society. Retrieved 14 September 2010.

- ^ "Sutton Park". Brumagem. Archived from the original on 11 September 2011. Retrieved 14 September 2010.

- ^ a b The Newcomen bulletin. Newcomen Society for the Study of the History of Engineering and Technology. 1984. p. 28. Retrieved 14 September 2010.

- ^ "For 60 years after the Norman Conquest, Sutton Coldfield was a royal manor". Sutton Coldfield Observer (republished by thisissuttoncoldfield.co.uk). Archived from the original on 5 May 2013. Retrieved 14 September 2010.

- ^ a b c Beresford, Maurice (1985). Time and Place: collected essays. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 100. ISBN 0-907628-39-7.

- ^ a b Riland-Bedford, William Kirkpatrick (2009) [1889]. Three Hundred Years of a Family Living; Being a History of the Rilands of Sutton Coldfield. General Books. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-150-13395-4.

- ^ Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1116386)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 14 September 2010.

- ^ Yates, George (1830). An Historical and Descriptive Sketch of Birmingham. Beilby, Knott, and Beilby. p. 24.

- ^ a b c d Showell, Walter; Harman, Thomas T. (1885). Showell's Dictionary of Birmingham. Birmingham: J.G. Hammond & Co. Retrieved 6 November 2010.

- ^ Jones, Douglas V. (1990). "Chapter III: Langley, Wishaw and Moxhull". Walmley and its surroundings. Westwood Press. ISBN 0-948025-11-5.

- ^ Noszlopy, George Thomas (2003). Public sculpture of Warwickshire, Coventry and Solihull. Liverpool University Press. p. 273. ISBN 0-85323-847-2.

- ^ a b Jones, Douglas V. (1994). The Royal Town of Sutton Coldfield—A Commemorative History. Westwood Press. ISBN 0-9502636-7-2.

- ^ Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1075794)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 14 September 2010.

- ^ Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1075793)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 14 September 2010.

- ^ Jones, Douglas V. (1990). Walmley and its surroundings. Westwood Press. ISBN 0-948025-11-5.

- ^ Wright, George (1837). A New and Comprehensive Gazetteer, Volume 4. Paternoster Row, London: T. Kelly. p. 567.

- ^ a b c "SUTTON COLDFIELD MASONIC HALL – A BRIEF HISTORY". The Sutton Coldfield Masonic Hall Company Ltd. Retrieved 6 November 2010.

- ^ General Report of the Board of Trade on the Railway and Canal Bills of Session 1859. Board of Trade. 1859. p. 52.

- ^ "Lichfield City Station". Rail Around Birmingham and the West Midlands. Retrieved 6 November 2010.

- ^ Butt, R.V.J. (1995). The Directory of Railway Stations. Yeovil: Patrick Stephens Ltd. p. 142. ISBN 1-85260-508-1.

- ^ a b "LMS Route: Water Orton to Walsall". Warwickshire Railways. Retrieved 6 November 2010.

- ^ McCulla, Dorothy (1976). Victorian and Edwardian Warwickshire: from old photographs. B. T. Batsford. p. 112. ISBN 0-7134-3101-6.

- ^ Bradshaw (1863). Bradshaw's Descriptive Railway Hand-book of Great Britain and Ireland. Oxford: Old House. pp. Section III, Page 21. ISBN 9781908402028.

- ^ Simmons, Jack (1978). The Railway in England and Wales, 1830–1914. Leicester University Press. p. 101. ISBN 0-7185-1146-8.

- ^ Smith, William (1830). A New & Compendious History of the County of Warwick. p. 367.

- ^ McCulloch, John Ramsay; Martin, Frederick (1866). A Dictionary, Geographical, Statistical, and Historical: Of the Various Countries, Places, and Principal Natural Objects in the World. Longmans. p. 246.

- ^ Bracken, L. (1860). History of the forest and chase of Sutton Coldfield. Benjamin Hall. p. 88.

- ^ Bracken, L. (1860). History of the forest and chase of Sutton Coldfield. Benjamin Hall. p. 87.

- ^ Bracken, L. (1860). History of the forest and chase of Sutton Coldfield. Benjamin Hall. p. 89.

- ^ "Potted History". South Staffordshire Water Archives. Retrieved 6 November 2010.

- ^ Boorman, Henry (1961). Newspaper Society, 125 years of progress. Kent Messenger. p. 144.

- ^ Hall, Sir John (1926). Trial of Abraham Thornton. William Hodge & Co. Ltd. pp. 1–2.

- ^ Hall, Sir John (1926). Trial of Abraham Thornton. William Hodge & Co. Ltd. pp. 4–5.

- ^ Hall, Sir John (1926). Trial of Abraham Thornton. William Hodge & Co. Ltd. pp. 7–9.

- ^ Thornbury, Walter (1879). Old Stories Re-Told (new ed.). Chatto and Windus. p. 234. Retrieved 2 August 2014.

- ^ Hall, Sir John (1926). Trial of Abraham Thornton. William Hodge & Co. Ltd. pp. 32–34.

- ^ Megarry, Sir Robert (2005). A New Miscellany-at-Law: Yet Another Diversion for Lawyers and Others. Hart Pub. p. 69. ISBN 1-58477-631-5. Retrieved 2 August 2014.

- ^ Hall, Sir John (1926). Trial of Abraham Thornton. William Hodge & Co. Ltd. p. 46.

- ^ Thornbury, Walter (1879). Old Stories Re-Told (new ed.). Chatto and Windus. p. 238. Retrieved 2 August 2014.

- ^ Hall, Sir John (1926). Trial of Abraham Thornton. William Hodge & Co. Ltd. pp. 55–56.

- ^ Theis, Michael. "A Print-out of the Preliminary Catalogue of the Max Lock Archive" (PDF). University of Westminster. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 3 November 2010.

- ^ ""Collapse of Brassington Avenue retirement home plans in Sutton Coldfield confirmed", Sutton Coldfield Observer, published 16 November 2016". Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 30 September 2016.

- ^ "Royal town calls for own council". BBC News. 20 July 2015.

- ^ "Information for Candidates and Agents - Sutton Coldfield Parish Council Elections - 5 May 2016 - Birmingham City Council". www.birmingham.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 23 April 2016. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ^ "Street Rankings 2007 National Report", Mouseprice.com. Retrieved 17 September 2007 Archived 6 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Lucia Adams and Michael Moran, "The ten most expensive places to live in Britain... and ten budget alternatives", The Times, 30 March 2007. Retrieved 17 September 2007

- ^ Anne Ashworth, "Why modest pensioners may be lumped in with London super-rich", The Times, 14 March 2007. Retrieved 17 September 2007

- ^ "Statues claimed". icSutton Coldfield. 18 October 2007. Archived from the original on 14 November 2007. Retrieved 22 October 2007.

- ^ Sainsbury's quits shopping centre, Birmingham Evening Mail, 27 February 2001

- ^ "Sutton Coldfield Town FC". Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ "Paget Rangers FC". Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ "Sutton Coldfield Golf Club". Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ "Walmley Golf Club". Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ "Aston Wood Golf Club". Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ "Moor Hall Golf Club". Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ "Little Aston Golf Club". Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ "Boldmere Golf Club". Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ "Walmley Sports Club". Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ "Four Oak Saints CC". Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ "Sutton Coldfield CC". Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ "Sutton Coldfield Hockey Club". Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ "England Hockey - Sutton Coldfield Hockey Club". Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ "Beacon Hockey Club". Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ "England Hockey - Beacon Hockey Club". Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ "Alliance International Hockey Club". Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ "Sutton Coldfield Fencing Club". Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1343333)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 20 September 2007.

- ^ "Birmingham City Council: High Street, Sutton Coldfield Conservation Area map". GB-BIR: Birmingham.gov.uk. 13 June 2009. Retrieved 2 August 2014.

- ^ "Birmingham City Council: Anchorage Road Conservation Area map". GB-BIR: Birmingham.gov.uk. 13 June 2009. Retrieved 2 August 2014.

- ^ "Holy Trinity Parish Church: History". Archived from the original on 22 December 2007.

- ^ "Birmingham.gov.uk: Bishop Vesey's Monument". Archived from the original on 10 June 2008.

- ^ Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1343304)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 20 September 2007.

- ^ Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1116360)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 20 September 2007.

- ^ Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1075800)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 20 September 2007.

- ^ Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1075801)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 20 September 2007.

- ^ Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1067116)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 20 September 2007.

- ^ Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1343300)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 20 September 2007.

- ^ Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1067123)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 20 September 2007.

- ^ Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1075798)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 20 September 2007.

- ^ category:Construction Of Birmingham Mission Offices, www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk, retrieved 6 October 2023