German bombing of Rotterdam

| The Rotterdam Blitz | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the German invasion of the Netherlands | |||||||

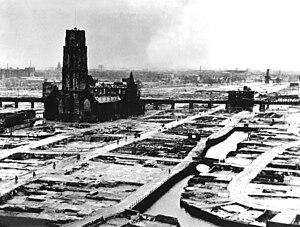

Rotterdam's city centre after the bombing. The heavily damaged (now restored) St. Lawrence church stands out as the only remaining building that is reminiscent of Rotterdam's medieval architecture. The photo was taken after the removal of all debris. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| P. W. Scharroo | Albert Kesselring | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

Luchtvaartafdeling (LVA) Marineluchtvaartdienst (MLD) | Luftflotte 2 | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| No remaining operational fighter aircraft[1] |

80 aircraft directly involved 700 involved in concurrent operations | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

1,150 killed, including 210 soldiers[2] LVA and MLD virtually destroyed[3] | 125[2] | ||||||

In 1940, Rotterdam was subjected to heavy aerial bombardment by the Luftwaffe during the German invasion of the Netherlands during the Second World War. The objective was to support the German troops fighting in the city, break Dutch resistance and force the Dutch army to surrender. Bombing began at the outset of hostilities on 10 May and culminated with the destruction of the entire historic city centre on 14 May,[2] an event sometimes referred to as the Rotterdam Blitz. According to an official list published in 2022, at least 1,150 people were killed, with 711 deaths in the 14 May bombing alone,[2] and 85,000 more were left homeless.

The psychological and the physical success of the raid, from the German perspective, led the Oberkommando der Luftwaffe (OKL) to threaten to destroy the city of Utrecht if the Dutch command did not surrender. The Dutch surrendered in the late afternoon of 14 May and signed the capitulation early the next morning.[4]

Prelude

[edit]The strategic location of the Netherlands between the United Kingdom and Germany made it ideal for the basing of German air and naval forces to be used in attacks on the British Isles. The Netherlands had firmly opted for neutrality throughout the First World War and had planned to do the same during the Second World War. It had refused armaments from France and made the case that it wanted no association with either side. Armament production was slightly increased after the German invasion of Denmark in April 1940, but the Netherlands had only 35 modern wheeled armoured fighting vehicles, five tracked armoured fighting vehicles, 135 aircraft, and 280,000 soldiers,[5] and Germany committed 159 tanks,[6] 1,200 modern aircraft,[citation needed] and around 150,000 soldiers to the Dutch theatre alone.[6]

With a significant military advantage, the German leadership intended to expedite the conquest of the country by first taking control of key military and strategic targets, such as airfields, bridges, and roads, and then using them to gain control of the remainder of the country. The first German plans to invade the Netherlands were articulated on 9 October 1939, when Hitler ordered, "Preparations should be made for offensive action on the northern flank of the Western Front crossing the area of Luxembourg, Belgium, and the Netherlands." The attack was to be carried out as quickly and as forcefully as possible.[7] Hitler ordered German intelligence officers to capture Dutch Army uniforms and to use them to gain detailed information on Dutch defensive preparations.[8]

The Wehrmacht launched its invasion of the Netherlands in the early hours of 10 May 1940. The attack started with the Luftwaffe crossing through Dutch airspace and giving the impression that Britain was the ultimate target. Instead, the aircraft turned around over the North Sea and returned to attack from the west and drop paratroopers at Valkenburg and Ockenburg Airfields, near the seat of government and Royal Palace in the Hague, starting the Battle for the Hague. Germany had planned to take control swiftly by using that strategy, but the assault on The Hague failed. However, bridges were taken at Moerdijk, Dordrecht and Rotterdam, which allowed armoured forces to enter the core region of "Fortress Holland" on 13 May.

Battle for Rotterdam

[edit]

The situation in Rotterdam on the morning of 13 May 1940 was a stalemate as it had been over the previous three days. Dutch garrison forces under Colonel P.W. Scharroo held the north bank of the Nieuwe Maas river, which runs through the city and prevented the Germans from crossing; German forces included airlanding and airborne forces of General Kurt Student and newly-arrived ground forces under General Schmidt, based on the 9th Panzer Division and the Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler, a motorized SS regiment. A portion of the 16th Air Landing Regiment that had landed outside the city had managed to fight their way into the city and capture key bridges, but they were soon surrounded and in danger of being overrun by Dutch attacks on their pocket. Outnumbered, with their numbers being reduced by casualties and ammunition running out, things were becoming desperate for the surrounded German paratroops.

A Dutch counterattack led by a Dutch marine company had failed to recapture the Willemsbrug traffic bridge,[9][10] the key crossing. Several efforts by the Dutch Army Aviation Brigade to destroy the bridge also failed.[11]

General Schmidt had planned a combined assault the next day, 14 May, using tanks of the 9th Panzer supported by flame throwers, SS troops and combat engineers.[12][13][14][15] The airlanding troops were to make an amphibious crossing of the river upstream and then a flank attack through the Kralingen district.[16][17] The attack was to be preceded by artillery bombardment, while Gen. Schmidt had requested the support of the Luftwaffe in the form of a Gruppe (about 25 aircraft) of Junkers Ju 87 dive-bombers, specifically for a precision raid.[18][19][20]

Schmidt's request for air support reached the staff of Luftflotte 2 in Berlin. Instead of a precision bombing, a carpet bombing by Heinkel He 111 bombers was carried out, with only a Gruppe of Stukas focusing on some strategic targets. The carpet bombing had been ordered by Hermann Göring, specifically to force a Dutch national capitulation.[21]

Negotiations

[edit]

The bombing was initially scheduled for 13 May, but low clouds made targeting impossible and the raid was postponed until the following day.[22] At roughly 10:30 on 14 May, General Rudolf Schmidt issued an ultimatum to the Dutch commander, Colonel Scharroo:[23]

To the Commander of Rotterdam

To the Mayor and aldermen and the Governmental Authorities of Rotterdam

The continuing opposition to the offensive of German troops in the open city of Rotterdam forces me to take appropriate measures should this resistance not be ceased immediately. This may well result in the complete destruction of the city. I petition you - as a man of responsibility - to endeavour everything within your powers to prevent the town of having to bear such a huge price. As a token of agreement I request you to send us an authorised negotiator by return. Should within two hours after the hand-over of this ultimatum no official reply be received, I will be forced to execute the most extreme measures of destruction.

The commander of the German troops.

The Mayor of Rotterdam, Pieter Oud, consulted with his aldermen and concluded that there was not enough time to evacuate the city within the two-hour period the Germans had set.[23] Mayor Oud pleaded with Scharroo to surrender.[23] However, Scharroo was not happy with the integrity of the letter as it had not been signed by anyone on the German side; therefore, he refused to seriously consider the surrender[23] and instead replied asking for further details:[23]

To the commander of the German troops.

I am in receipt of your letter. Subject letter has not been duly signed and did not mention name and rank of its originator. Prior to seriously considering your proposal, the letter should be duly signed and mention your name and rank.

Colonel, commander of the Dutch troops in Rotterdam, P.W. Scharroo

On receipt of Scharroo's letter, Schmidt sent a telegram to the 2nd Luftflotte (responsible for the air raid) stating:[23]

Airstrike postponed due to ongoing negotiations. Return to stand-by status.

The 2nd Luftflotte received the message at 12:42, but did not forward it to the bombers, who were en route. As Schmidt was handing over his second signed ultimatum to the Dutch negotiators, the group heard aircraft engines overhead.[24] Schmidt was shocked.[24]

It had been arranged that the Wehrmacht would shoot red flares into the sky if negotiations had begun,[23][25][26] signalling the bombers to turn back. However, two groups of Heinkel He 111 bombers were approaching the city: 36 from the south and 54 from the northeast, which was still held by the Dutch.[23] The smaller bombing group in the south saw the flares and most of its planes turned back, but the larger group proceeded to destroy the city.[23][25][26] General Schmidt exclaimed, "My God, this is a catastrophe!"[23]

Bombing

[edit]In total, 1,150 50-kilogram (110 lb) and 158 250-kilogram (550 lb) bombs were dropped on the city, mainly in the residential areas of Kralingen and the medieval city centre. Most of them struck buildings, which immediately went up in flames. The fires across the city centre spread uncontrollably and, in the subsequent days, were aggravated as the wind grew stronger; they merged to become a firestorm. Reports stated that 900 people had reported been killed and 642 acres (2.60 km2) of the city centre had been destroyed.[27] 24,978 homes,[27] 24 churches, 2,320 stores, 775 warehouses, and 62 schools were destroyed.

50 kilometres away in Utrecht, Cornelia Fuykschot described the aftermath:

…a haze began to cover the western sky, and as the sun had passed the zenith and moved westward, it grew redder and redder, until it finally hung there as a glowing red ball in the midst of a dark grey sky. One could easily look at it with the naked eye now, it was more like a moon, except that the deep red began to turn almost brown. As the haze came nearer, it turned the glorious spring day into a gloomy mid-November darkness, and as we stood there gazing at the sky and not understanding what was happening, a flake of paper came down, and another one, and more…. Some were charred, around the edges, some had flowers on them like wallpaper, others print. Where were they from? Was there a fire somewhere? If so, it had to be a gigantic fire to blacken the sky like this.[28]: 159

Schmidt sent a conciliatory message to the Dutch commander General Winkelman, who surrendered shortly afterwards at Rijsoord, a village southeast of Rotterdam. The school where the Dutch capitulated was later turned into a small museum.

Responsibility

[edit]This section may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: Reads like a persuasive essay citing primary sources. Should be a summary of how secondary sources allocate responsibility, and factual details. (April 2024) |

The telegraphed message from Schmidt to halt the bombers and put them on standby was confirmed as received by the 2nd Luftflotte at 12:42.[23] The commander of Luftflotte 2, Field Marshal Albert Kesselring was interviewed about the event during the Nuremberg Trials by Leon Goldensohn, who recalled:[29]

Kesselring admitted that the conditions were such that an attack could have been called off, but still clung, rather unreasonably, to the idea that it was tactically indicated because he had been ordered to do so, and he was not a politician but a soldier

Kesselring stated that he had not known about the capitulation, but that is contradicted by the evidence that his headquarters had received the message at 12:42, roughly 40 minutes before the bombs started to fall. Yet, at Nuremberg, both Göring and Kesselring of the Luftwaffe defended the bombing on the grounds that Rotterdam was not an open city but one stoutly defended by the Dutch. That said, it would be unreasonable for the Germans to bomb a captured city as that would mean it was occupied by their own troops. The often omitted fact that German troops were holding out in a pocket within the city negates allied claims that it was an indiscriminate carpet bombing of the sort the Allies later employed themselves. [24] In his memoirs, written while he was in prison for war crimes, Kesselring gave his account:[30]

On the morning of 13 May, Student kept calling for bomber support against enemy strongpoints inside Rotterdam and the point of main effort at the bridges where the parachutists were held up. At 14:00 hours the sortie in question was flown, and its success finally led to the capitulation of Holland on 14 May 1940

General Student had requested strikes against enemy strongpoints, not carpet-bombing of the city. Had the Germans indiscriminately carpet bombed the city, they would have endangered their own troops holding out around the bridges. [30] Kesselring also states in his memoirs that he spent hours in heated argument with Göring on how the attacks were to be carried out, if at all.[30] The arguments happened before the bombers took off and so that cannot be used as an excuse for why he did not get in contact with the bombers.

The fact was that he had already admitted at Nuremberg that he was for the attack since he wanted "to present a firm attitude and secure an immediate peace" or take "severe measures". Kesselring further states:[30]

As a result I repeatedly warned the bomber wing-commander to pay particular attention to the flares and signals displayed in the battle area and to keep in constant wireless contact with the Air-landing Group.

With that in mind, it is unlikely that the bombers would have reeled in their antennas until a few minutes before releasing their bombs. The argument that the antennas were reeled in is contradicted also by the fact that Kesselring quotes Oberst Lӓckner (the commander of the bombers) in his memoirs:[31]

Shortly before the take-off a message came through from Air command saying that Student had called upon Rotterdam to surrender and ordering us to attack an alternative target in case Rotterdam should have surrendered in the meantime (during the approach flight) ― Oberst Lӓckner

That invalidates the argument that the bombers had reeled in their antennas because the bombers had not taken off. That indicates that Kesselring must have made the decision to attack Rotterdam regardless of the negotiations.[citation needed]

Aftermath

[edit]

The Dutch military had no effective means of stopping the bombers (the Dutch Air Force had practically ceased to exist, and its anti-aircraft guns had been moved to The Hague), so when a similar ultimatum was given in which the Germans threatened to bomb the city of Utrecht, the Dutch supreme command decided to capitulate in the late afternoon, rather than risk the destruction of another city.[32][33] Through Allied and international news media, Dutch and British sources informed the public that the raid on Rotterdam had been on an open city in which 30,000 civilians were killed (the real number of civilians who were killed was around 900) "and character[ised] the German demolition of the old city as an act of unmitigated barbarism."[34] The number of casualties was relatively small, because thousands of civilians had either fled to safer parts of Rotterdam, or they had fled to other cities, during the previous four days of bombing and warfare.[35] The German weekly Die Mühle (The Windmill) stated that the Dutch government was to blame for turning Rotterdam into a fortress, despite multiple summons to evacuate. It also claimed that the old city was ignited by Dutch bombs and incendiary devices.[36]

The United Kingdom had followed a policy of only bombing military targets and infrastructure, such as ports and railways, because it considered them militarily important.[37] While the British government acknowledged the fact that the bombing of Germany would cause civilian casualties, it renounced the deliberate bombing of civilian property outside combat zones, which, after the fall of Poland, meant German areas which were located east of the Rhine, as a military tactic. That policy was abandoned on 15 May 1940, one day after the Rotterdam Blitz, when the RAF was directed to attack targets which were located in the Ruhr, including oil plants and other civilian industrial targets that aided the German war effort, such as blast furnaces that were self-illuminating at night. The first RAF raid on the interior of Germany took place on the night of 15/16 May 1940.[38][39]

When the invasion of Holland took place I was recalled from leave and went on my first operation on 15 May 1940 against mainland Germany. Our target was Dortmund and on the way back we were routed via Rotterdam. The German Air Force had bombed Rotterdam the day before and it was still in flames. I realised then only too well that the phoney war was over and that this was for real. By that time the fire services had extinguished a number of fires, but they were still dotted around the whole city. This was the first time I'd ever seen devastation by fires on this scale. We went right over the southern outskirts of Rotterdam at about 6,000 or 7,000 feet, and you could actually smell the smoke from the fires burning on the ground. I was shocked seeing a city in flames like that. Devastation on a scale I had never experienced.

— Air Commodore Wilf Burnett.[40]

Reconstruction

[edit]

Now the biggest bank structure in Europe rears its rounded, balloon-hanger bulk out of the bomb made desert. This is the new home of the Rotterdamsche Bank. Behind its grilled windows flows the golden blood of commerce. Half a mile away, the cement spattered wooden forms of a huge, new wholesale mart climb to knobby squares above the flat sands. Wholesalers already do business on the ground floor while fresh concrete flows into the forms two floors higher. Along the waterfront, a couple of miles down the New Meuse (nieuwe Maas) river, cranes lever the bales and boxes of an industrial world in and out of the new warehouses.

— Cairns Post newspaper article, 1950.[41]

The extent of the damage from the bombardment and the resulting fire caused an almost immediate decision to demolish the entire city centre with the exception of the Laurenskerk church, the De Noord mill, the Beurs trade centre, the Rotterdam city hall (nl:Stadhuis van Rotterdam) and the Rotterdam old central post office (nl:Hoofdpostkantoor (Rotterdam)).[27][42] Despite the disaster, the city's destruction was regarded as the perfect opportunity to redress many of the problems of industrial pre-war Rotterdam, such as crowded, impoverished neighborhoods,[43] and to introduce broad-scale, modernising changes in the urban fabric, which had previously been too radical in the built-up city.[44] There seemed to be no thought of nostalgically rebuilding the old city,[45] as it would be at the expense of a more modern future.[46] That ran counter to the decision taken in other European cities destroyed during the war, such as Warsaw, for which the Polish government spent considerable resources on reconstructing historical buildings and quarters and restoring them to their prewar appearance.

W.G. Witteveen, director of the Port Authority, was instructed to draw up plans for the reconstruction within four days of the bombing,[47] and presented his plan to the city council in less than a month.[27][43] The first plan essentially used most of the old city's structure and layout, but it integrated them into a new plan with widened streets and sidewalks.[42][47] The largest and most controversial change in the layout was to move the main dike of the city alongside the riverbank, so as to protect the low-lying Waterstad area from flooding.[43] That was met with criticism from the newly-formed Inner Circle of the Rotterdam Club, which promoted integrating the city with the Maas (Meuse), and claimed that the dike would create a marked separation from it.[43] A number of new or previously-incomplete projects, such as the Maastunnel and Rotterdamsche bank, were to be completed in accordance with Witteveen's plan, and the projects kept the Dutch people in work during the German occupation of the city until all construction was halted in 1942.[27][47] Herman van der Horst's 1952 documentary Houen zo! presents a vision of some of the projects.[48] Meanwhile, Witteveen's successor Cornelius van Traa drafted a completely new reconstruction plan, the Basisplan voor de Herbouw van de Binnenstad, which was adopted in 1946.[42][43] Van Traa's plan was a much more radical rebuild, doing away with the old layout and replacing them with a collection of principles rather than such a rigid structural design.[47] The Basisplan placed a high emphasis on broad open spaces and promoted the river's special integration with the city through two significant elements: the Maas Boulevard, which reimagined the newly-moved dike as a tree-lined street 80 wide, and the Window to the River, a visual corridor running from the harbour to the centre of the city.[43] Both were meant to show the workings of the harbour to the city's people.

Because reconstruction work began so rapidly after the bombing, the city had by 1950 regained its reputation as the fastest loading and unloading harbour in the world.[49]

Around the same time, the city centre of Rotterdam had shifted north-west as a result of temporary shopping centres, which had been set up on the edge of the devastated city,[43] and new shopping centre projects like the Lijnbaan were expressing the radical new concepts of the Basisplan, through low, wide open streets set beside tall slab-like buildings.[46] Rotterdam's urban form was more American than other Dutch cities, based on US plans,[46] with a large collection of high-rise elements[42] and the Maas boulevard and Window to the River functioning primarily as conduits for motor vehicles.[43] In later years, Rotterdam architect Kees Christiaanse wrote:

Rotterdam did indeed resemble an American provincial city. You could drive leisurely in a big car through the broad streets and revel in the contrasts between emptiness and density. The Rotterdam police drove around in huge Chevrolets...and the Witte Huis was the first high-rise building in Europe with a Chicago-type steel skeleton and a ceramic façade.

— Kees Christiaanse, Rotterdam.[50]

The larger-scale 'wholesale-quantity' approach was equally used for hospitals and parks (such as Dijkzigt Hospital and Zuider Park) as retail centres,[47] but close attention was still paid to creating human-scale walkable promenades, especially that of the Lijnbaan, which presented broad sunny walkways for shoppers and spectators, and tried new retail techniques such as open glass walls to blend interior and exterior.[46]

While urban reconstruction can be fraught with complexity and conflict,[44] Rotterdam's status as a 'working' harbour city meant it did not receive the same resistance to rebuilding as a cultural or political centre (as Amsterdam or The Hague) might have.[47] However, there was still significant movement of people away from the city centre during Rotterdam's reconstruction to purpose-built neighbourhoods such as De Horsten and Hoogvliet, which are now inhabited by mainly lower-income households.[51]

Today, van Traa's Basisplan has been almost completely replaced with newer projects. For example, The Maritime Museum blocks the Window to the River, and Piet Blom's Cube Houses create another barrier between the city and the river, where the Basisplan had envisaged a connection between them.[42] The Euromast Tower, which was built in 1960, is a related attempt to create a visual link between the city and the port, seemingly one of the last architectural structures that is related to van Traa's Basisplan[43] before later attempts like the Boompjes Boulevard in 1991.[52]

See also

[edit]- Allied bombing of Rotterdam

- List of World War II military aircraft of Germany

- List of Dutch military equipment of World War II

Notes

[edit]- ^ De luchtverdediging mei 1940, by F.J. Molenaar. The Hague, 1970.

- ^ a b c d "First official list of victims of Rotterdam bombing published after 82 years". DutchNews.nl. 12 April 2022. Retrieved 12 April 2022.

- ^ Hooton 2007, p. 79.

- ^ Hooton 2007, p. 52.

- ^ Goossens 2011, Dutch army unit organisation.

- ^ a b Goossens 2011, German strategy 10 May 1940: German invasion army strength

- ^ The Nizkor Project 1991, p. 766.

- ^ Foot 1990, p. [page needed].

- ^ Brongers 2004, (ONR Part III), p. 83

- ^ Amersfoort 2005, p. 364.

- ^ Brongers 2004, (ONR Part I), pp. 242,243

- ^ Brongers 2004, (ONR Part III), pp. 204, 205

- ^ Amersfoort 2005, p. 367.

- ^ Pauw 2006, p. 75.

- ^ Götzel 1980, p. 145.

- ^ Götzel 1980, p. [page needed].

- ^ Kriegstagebuch, KTB IR.16, 22.ID BA/MA

- ^ Brongers 2004, (ONR Part III), p. 201

- ^ Amersfoort 2005, p. 368.

- ^ Götzel 1980, pp. 146, 147.

- ^ Goossens 2011, Rotterdam: Introduction – a recapitulation; Brongers 2004, (ONR Part III), p. 232; Amersfoort 2005, pp. 368, 369;Pauw 2006, p. 74; Götzel 1980, pp. 146–151; Lackner 1954, p. [page needed] [full citation needed]

- ^ Hooton, E. R. (1996). Phoenix triumphant: the rise and rise of the Luftwaffe (New ed.). Arms and Armour Press. p. 249. ISBN 1-85409-331-2. OCLC 60274266.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Allert M.A. Goossens. "Rotterdam". War Over Holland. Archived from the original on 31 October 2020.

- ^ a b c Shirer, William L. (1960). The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. New York. p. 867. ISBN 0-671-62420-2. OCLC 1286630.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Hooton, E. R. (1996). Phoenix triumphant : the rise and rise of the Luftwaffe (New ed.). Arms and Armour Press. p. 249. ISBN 1-85409-331-2. OCLC 60274266.

- ^ a b Macksey, Kenneth; Zenon Miernicki (2004). "The Nemesis of Incomprehension". Kesselring. Warsaw: Bellona. ISBN 83-11-09743-7. OCLC 749589540.

- ^ a b c d e Helen Hill Miller (October 1960). "Rotterdam - Reborn from Ruins". National Geographic. 118 (4): 526–553.

- ^ Fuykschot, Cornelia (2019). Hunger in Holland. Prometheus Publishing. ISBN 9780879759872.

- ^ Goldensohn, Leon (2005). The Nuremberg interviews : an American psychiatrist's conversations with the defendants and witnesses. Robert Gellately (1st ed.). New York: Vintage Books. p. 326. ISBN 1-4000-3043-9. OCLC 69671719.

- ^ a b c d Kesselring, Albert (2015). The memoirs of Field-Marshal Kesselring. Stroud. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-7509-6434-0. OCLC 994630181.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Kesselring, Albert (2015). The memoirs of Field-Marshal Kesselring. Stroud. pp. 56–58. ISBN 978-0-7509-6434-0. OCLC 994630181.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Brongers 2004, (ONR Part III), p. 263.

- ^ Amersfoort 2005, p. 183.

- ^ Hinchcliffe 2001, p. 43; DeBruhl 2010, pp. 90–91 and Grayling 2006, p. 35 for the quote.

- ^ Wagenaar 1970, pp. 75–303.

- ^ Die Mühle, no.22, 31 May 1940, Moritz Schäfer Verlag, Leipzig

- ^ Hastings 1999, pp. 54–56.

- ^ Grayling 2006, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Taylor 2005, Chapter "Call Me Meier", p. 111.

- ^ Burnett 2008.

- ^ Cairns Post 1950.

- ^ a b c d e Christiaanse 2012, pp. 7–17.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Meyer 1999, pp. 309–328.

- ^ a b Diefendorf 1990, pp. 1–16.

- ^ Cairns Post 1950.

- ^ a b c d Taverne 1990, pp. 145–155.

- ^ a b c d e f Runyon 1969.

- ^ Horst 1952.

- ^ Nambour Chronicle and North Coast Advertiser 1950.

- ^ Christiaanse 2012, pp. 19.

- ^ Kleinhans, Priemus & Engbersen 2007, pp. 1069–1091.

- ^ Christiaanse 2012, pp. 46.

References

[edit]- Amersfoort, H; et al. (2005), Mei 1940 – Strijd op Nederlands grondgebied (in Dutch), SDU, ISBN 90-12-08959-X

- Brongers, E.H. (2004), Opmars naar Rotterdam (in Dutch), Aspect, ISBN 90-5911-269-5

- Burnett, Wilf (7 October 2008), "Flying over Rotterdam", Early Days, Personal Stories, Bomber Command Association, archived from the original on 21 January 2016, retrieved 16 August 2017

- "Rotterdam Rises Again", Cairns Post, Queensland, Australia, p. 2, 2 March 1950

- Christiaanse, Kees (2012), Rotterdam, Rotterdam: 010 Publishers, ISBN 978-90-6450-772-4

- DeBruhl, Marshall (2010), Firestorm: Allied Airpower and the Destruction of Dresden (unabridged ed.), Random House Publishing Group, pp. 90–91, ISBN 9780307769619

- Diefendorf, Jeffry M. (1990), Rebuilding Europe's bombed cities, Basingstoke: Macmillan, ISBN 0-333-47443-0

- Foot, M.R.D. (1990), Holland at war against Hitler: Anglo-Dutch relations, 1940–1945, Psychology Press, ISBN 978-0-7146-3399-2

- Goossens, Allert (2011), Welcome, website of 1998–2009 Stichting Kennispunt Mei 1940

- Götzel, H (1980), Generaloberst Kurt Student und seine Fallschirmjäger (in German), Podzun-Pallas Verlag, ISBN 3-7909-0131-8, OCLC 7863989

- Grayling, A.C. (2006), Among the Dead Cities, London: Bloomsbury Publishing, ISBN 0-7475-7671-8

- Hastings, Max (1999), Bomber Command, London: Pan Books, ISBN 978-0-330-39204-4

- Hinchcliffe, Peter (2001) [1996], The other battle: Luftwaffe night aces versus Bomber Command, Airlife Publishing, ISBN 978-1-84037-303-5

- Hooton, Edward (1994), Phoenix Triumphant; The Rise and Rise of the Luftwaffe, London: Arms & Armour Press, ISBN 1-86019-964-X

- Hooton, Edward (2007), Luftwaffe at War; Blitzkrieg in the West, London: Chevron/Ian Allan, ISBN 978-1-85780-272-6

- Jong, dr. L de (3 May 1940), Het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden in de Tweede Wereldoorlog deel (in Dutch), p. 352

- Horst, Herman van der (1952), Houen zo! (in Dutch)

- ?. Kriegstagebuch IR.16, May 1940[full citation needed]

- Kleinhans, R.; Priemus, H.; Engbersen, G. (2007), "Understanding Social Capital in Recently Restructured Urban Neighbourhoods: Two Case Studies in Rotterdam.", Urban Studies, 44 (5/6), Urban Studies (Routledge): 1069–1091, Bibcode:2007UrbSt..44.1069K, doi:10.1080/00420980701256047

- Lackner, a.D. (Gen-Lt) (1954), Bericht Einsatz des KG.54 auf Rotterdam (in German), Freiburg: Bundesarchiv Militärarchiv

- Meyer, Han (1999), City and port : urban planning as a cultural venture in London, Barcelona, New York, and Rotterdam : changing relations between public urban space and large-scale infrastructure., Utrecht: International Books, ISBN 90-5727-020-X

- "Rotterdam Raised From Ruins", Nambour Chronicle and North Coast Advertiser, Queensland, Australia, p. 2, 17 November 1950

- Nederlands Omroep Stichting (NOS) (10 December 2008), Veel meer gewonden in mei 1940. (in Dutch), archived from the original on 3 March 2009

- Pauw, J.L. van der (2006), Rotterdam in de Tweede Wereldoorlog (in Dutch), Uitgeverij Boom, ISBN 90-8506-160-1

- The Nizkor Project (1991), "Chapter IX: Aggression Against Belgium, The Netherlands and Luxembourg (Part 3 of 6)", Nazi Conspiracy & Aggression, vol. I, pp. 766–768, archived from the original on 5 March 2016, retrieved 14 January 2013

- Runyon, David (1969), An analysis of the rebuilding of Rotterdam after the bombing on May 14, 1940, University of Wisconsin

- Roep, Thom; Loerakker, Co (1999), Van Nul to Nu Deel 3 – De vaderlandse geschiedenis van 1815 tot 1940 (in Dutch), p. 42 square 2, ISBN 90-5425-098-4

- Speidel, Wilhelm (General der Flieger) (1958), "Chief of Staff Luftflotte 2 Western theatre January–October 1940 (K113-107-152)", The campaign in Western-Europe 1939–1940, Washington archives

- Taverne, E.R.M. (1990), The Lijnbaan (Rotterdam): a Prototype of a Postwar Urban Shopping Centre, in Rebuilding Europe's bombed cities, J.M. Diefendorf, Editor., Basingstoke: Macmillan, ISBN 0-333-47443-0

- Taylor, Frederick (2005), Dresden: Tuesday, 13 February 1945, London: Bloomsbury, ISBN 0-7475-7084-1

- Wagenaar, Aad (1970), Rotterdam mei '40: De slag, de bommen, de brand (in Dutch), Amsterdam: De Arbeiderspers, ISBN 90-204-1961-7

Further reading

[edit]- Google Earth overlay of the area destroyed in the Blitz Archived 8 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Rotterdam Blitz with timeline

- Spaight. James M. "Bombing Vindicated" G. Bles, 1944. OCLC 1201928 (Spaight was Principal Assistant Secretary of the Air Ministry (U.K))

- Pictures

- "Pictures of Rotterdam after the Blitz". Archived from the original on 31 August 2016.

- Pictures of the 2007 and 2008 commemoration by Mothership art producers Archived 19 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine