Romance of the Western Chamber

Romance of the Western Chamber (traditional Chinese: 西廂記; simplified Chinese: 西厢记; pinyin: Xīxiāng Jì; Wade–Giles: Hsi-hsiang-chi), also translated as The Story of the Western Wing, The West Chamber, Romance of the Western Bower and similar titles, is one of the most famous Chinese dramatic works. It was written by the Yuan dynasty playwright Wang Shifu (王實甫), and set during the Tang dynasty. Known as "China's most popular love comedy,"[1] it is the story of a young couple consummating their love without parental approval, and has been seen both as a "lover's bible" and "potentially lethal," as readers were in danger of pining away under its influence.[2]

Contents of the play

[edit]

Play I, Burning Incense and Worshiping the Moon

Play II, Icy Strings Spell Out Grief

Play III, Feelings Transmitted by Lines of Poetry

Play IV, A Clandestine Meeting of Rain and Clouds

Play V, A Reunion Ordained by Heaven

Plot

[edit]

The play has twenty-one acts in five parts. It tells the story of a secret love affair between Zhang Sheng (张生), a young scholar, and Cui Yingying, the daughter of a chief minister of the Tang court. The two first meet in a Buddhist monastery. Yingying and her mother have stopped there to rest while escorting the coffin of Yingying's father to their native town. Zhang Sheng falls in love with her immediately, but is prevented from expressing his feelings while Yingying is under her mother's watchful eye. The most he can do is express his love in a poem read aloud behind the wall of the courtyard in which Yingying is lodging.[3]

However, word of Yingying's beauty soon reaches Sun the Flying Tiger, a local bandit. He dispatches ruffians to surround the monastery, in the hopes of taking her as his consort. Yingying's mother agrees that whoever drives the bandits away can have Yingying's hand in marriage, so Zhang Sheng contacts his childhood friend General Du, who is stationed not far away. The general subdues the bandits, and it seems that Zhang Sheng and Cui Yingying are set to be married. However, Yingying's mother begins to regret her rash promise to Zhang Sheng, and takes back her word, with the excuse that Yingying is already betrothed to the son of another high official of the court. The two young lovers are greatly disappointed, and begin to pine away with their unfulfilled love. Fortunately, Yingying's maid, Hongniang, takes pity on them, and ingeniously arranges to bring them together in a secret union. When Yingying's mother discovers what her daughter has done, she reluctantly consents to a formal marriage on one condition: Zhang must travel to the capital and pass the civil service examination. To the joy of the young lovers, Zhang Sheng proves to be a brilliant scholar, and is appointed to high office. The story thus ends on a happy note, as the two are finally married.[3]

Historical development

[edit]

The original story was first told in a literary Chinese short story written by Yuan Zhen during the Tang dynasty. This version was called The Story of Yingying, or Yingying's Biography. This version differs from the later play in that Zhang Sheng ultimately breaks from Yingying, and does not ask for her hand in marriage. Despite the unhappy ending, the story was popular with later writers, and recitative works based on it began accumulating in the centuries that followed. Perhaps bowing to popular sentiment, the ending gradually changed to the happy one seen in the play. The first example of the modified version is a chantefable (諸宮調, zhu gongdiao) titled Romance of the Western Chamber Zhu Gongdiao (西廂記諸宮調) by Master Dong (董解元, Dong Jieyuan, Jieyuan is an honorific meaning "master") of the Jin dynasty (1115–1234).[5] Wang Shifu's play was closely modeled on this version.[6]

Reactions

[edit]Due to scenes that unambiguously described Zhang Sheng and Cui Yingying fulfilling their love outside of the bond of marriage, moralists have traditionally considered The Story of the Western Wing to be an indecent, immoral, and licentious work. It was thus placed high on the list of forbidden books. Tang Laihe is reported to have said, "I heard that in the 1590s the performance of the Hsi-hsiang chi...was still forbidden among [good] families." Gui Guang (1613–1673) called the work "a book teaching debauchery." On the other hand, the famous critic Jin Shengtan considered it silly to declare a book containing sex to be immoral, since "If we consider [sex] more carefully, what day is without it? What place is without it? Can we say that because there is [sex] between Heaven and Earth, therefore Heaven and Earth should be abolished?".[7]

Since the appearance of this play in the thirteenth century, it has enjoyed unparalleled popularity.[who?] The play has given rise to innumerable sequels, parodies, and rewritings; it has influenced countless later plays, short stories, and novels and has played a crucial role in the development of drama criticism.

The theme of the drama is an attack on traditional mores, supporting the longing of young people in those days for freedom of marriage, although it follows the timeworn pattern of a gifted scholar and a beautiful lady falling in love at first sight. According to the orthodox viewpoint of Confucian society, love was not supposed to be a basis for marriage, as most marriages were arranged by the parents of the couples, but the happy ending of The Romance of the Western Chamber embodies the aspirations of people for more meaningful and happier lives.

Thus, the biggest difference between The Story of Yingying and The Story of the Western Wing lies in their endings—the former has a sad ending while the latter has a happy ending. What's more,The Romance of the Western Chamber carries a more profound meaning in its conclusion, and directly suggests the ideal that all lovers in the world be settled down in a family union, with a more sharp-cut theme of attacking traditional mores and the traditional marriage system.

Cultural influences

[edit]

Since the first performance, The Romance of the Western Chamber has become the most popular love comedy in China. Nowadays, it is still actively performed on the stage. In the original traditional forms of art performance, such as Kun Opera and Beijing Opera, and other new forms of performance like musical and film. The resourceful maidservant Hongniang in the story is so prominent that evolves from a supporting role to an indispensable main character, becoming the synonym of marriage matchmaker in Chinese culture. In some local versions, the plays even is named by her name and the story itself is only slightly changed. The Romance of the Western Chamber also had profound influences on other literary works, such as Dream of the Red Chamber, the first of China's Four Great Classical Novels, and another famous play, The Peony Pavilion, in the Ming dynasty. Jia Baoyu and Lin Daiyu reading Romance of the Western Chamber together is a very famous episode in the Dream of the Red Chamber. In chapter twenty-three, Lin Daiyu is surprised to find that Jia Baoyu is reading the play because in the Qing dynasty, this book was forbidden to read. At first, Baoyu tries to hide the book, but he could not hide it from her. Later, he expressed his love for Lin Daiyu through the famous sentences from the book.

Artistic achievement

[edit]

Artists working in different media—including painting, woodblock printmaking, and pottery decoration—drew upon the various literary works that told the story of Zhang Sheng and Cui Yingying, and their work relates to developments in Chinese literature and drama.[8]

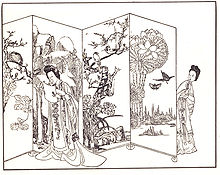

In the late Ming and early Qing dynasties, art that illustrated novels and dramatic productions became increasingly popular, and illustrations of The Romance of the Western Chamber were the most popular of all. Various Ming painters designed illustrations of the story, including Qian Gu, Tang Yin, and Chen Hongshou. One of the most accomplished renditions of the tale is the series of woodblock prints published, and probably designed, by Min Qiji (1580–after 1661) of Wucheng, Zhejiang province. His work, which dates to 1640, includes a frontispiece depicting Cui Yingying as well as one image for each of the twenty acts of the Yuan dynasty drama by Wang Shifu. Min Qiji's album may also be one of the first to rely on the Chinese taoban 套板 printing technique, using six colors to fill in contours but also to add modeling and shading to the depicted images. A significant innovation of Min Qiji's album is the presentation of scenes as if they were representations of dramatic performances or already-existing pictorial illustrations: the characters of the story appear as if they were paintings on handscrolls, folding fans, or standing screens; inscriptions on a bronze vessel; decorations on a lantern; and puppets used in a theatrical performance. It is possible that the innovative compositions of this album derive from designs by the Yuan artist Sheng Mao, also known as Sheng Mou (1271–1368).[9] The album was likely meant to appeal to a wealthy customer who was a fan of the story.[10]

From the 13th century to the 21st century, many scenes from The Romance of the Western Chamber decorated Chinese porcelain, although these have not been consistently recognized. Scenes from The Romance of the Western Chamber appear in porcelain of different periods, including the late Ming and early Qing dynasties. For example, the image of Yingying burning incense in the garden has become an archetype in Chinese art and is identifiable in decorated ceramics of the Jin, Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties.[11] Literary and dramatic scenes became popular as decorative patterns on blue-and-white porcelain produced in the Zhizheng era (1341–1367) of the Yuan dynasty.[12] Allusions to The Romance of the Western Chamber in porcelain do not only draw upon Wang Shifu's drama in the 13th century, but also relate to early poetry inspired by narratives of the Song dynasty, as well as dramas and story-telling performances of songs in the Jin dynasty.[13]

Translations

[edit]There have been numerous English translations:

- The Romance of the Western Chamber (1935), translated by Hsiung Shih-I, Methuen Publishing

- The West Chamber (1936), translated by Henry H. Hart, Oxford University Press (Hart did not translate the last act)

- The Western Chamber (1958), translated by Hung Tseng-ling, Foreign Languages Press

- The Romance of the Western Chamber (1973), translated and adapted by T.C. Lai and Ed Gamarekian, Heinemann Educational Books (Asia) Ltd. (Writing in Asia Series), with a foreword by Lin Yutang

- The Story of the Western Wing (1995), translated by Stephen H. West and Wilt L. Idema, University of California Press[14]

- Romance of the Western Bower (2000), translated by Xu Yuanchong and Xu Ming, Foreign Languages Press (bilingual version)

The book was translated into Manchu as Möllendorff: Manju nikan Si siang ki.[15] Vincenz Hundhausen made a German translation of this story.[16] A French translation was made by Stanislas Julien in 1872.

Adaptations

[edit]It was a released as a silent film Romance of the Western Chamber in China in 1927, directed by Hou Yao. In 2005, the TVB series Lost in the Chamber of Love made a twist in the tale and had Hongniang, played by Myolie Wu, falling in love with Zhang Sheng, played by Ron Ng, while Cui Yingying, played by Michelle Ye, would marry Emperor Dezong of Tang, played by Kenneth Ma.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- Delbanco, Dawn Ho (1983). "The Romance of the Western Chamber: Min Qiji's Album in Cologne." Orientations 14, no. 6 (June): 12-23.

- Hsu, Wen-Chin (2011). "Illustrations of Romance of the Western Chamber on Chinese Porcelains: Iconography, Style, and Development." Ars Orientalis 40, 39-107, available http://www.jstor.org/stable/23075932

- Merker, Annette. "Vincenz Hundhausen (1878-1955): Leben und Werk des Dichters, Druckers, Verlegers, Professors, Regisseurs und Anwalts in Peking" (book review). China Review International. Volume 8, Number 1, Spring 2001. pp. 241–244. 10.1353/cri.2001.0034. - Available from Project MUSE.

- Song, Rui-bin. On the Role's Evolution of Hongniang in "The Romance of West Chamber". Jixi University, Jixi, Heilongjiang, May 2009, https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/23075932.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3Aaa74969e64dd0379542dc207c7496b1b

- Wang, Shifu, edited and translated with an introduction by Stephen H. West and Wilt L. Idema (1995). The Story of the Western Wing. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- West, Stephen H., and Wilt L. Idema (1995). “The Status of Wang Shifu’s Story of the Western Wing in Chinese Literature.” In The Story of the Western Wing, by Wang Shifu. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 3–15.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Shifu Wang (1991). "The Story of the Western Wing". Translated by Stephen H. West and Wilt L. Idema. University of California Press., p. 3.

- ^ Rolston, David L. (March 1996). "(Book Review) The Story of the Western Wing". The China Quarterly (145): 231–232. doi:10.1017/S0305741000044477. JSTOR 655679. S2CID 154354686.

- ^ a b Wang, John Ching-yu (1972). Chin Sheng-T'an. New York: Twayne Publishers, Inc. pp. 82–83.

- ^ Wu, Hung (1996). "The Painted Screen". Critical Inquiry. 23 (1): 50. doi:10.1086/448821. JSTOR 1344077. S2CID 153464769.

- ^ Ch'en, Li-Li (1976). Master Tung's Western Chamber Romance (Tung Hsi-hsiang Chu-kung-tiao): A Chinese Chantefable. 9780521208710. ISBN 9787310049905 – via Google Books.

- ^ Wang, John Ching-yu (1972). Chin Sheng-T'an. New York: Twayne Publishers, Inc. pp. 83–84.

- ^ Wang, John Ching-yu (1972). Chin Sheng-T'an. New York: Twayne Publishers, Inc. p. 84.

- ^ Hsu, Wen-Chin (2011). "Illustrations of Romance of the Western Chamber on Chinese Porcelains: Iconography, Style, and Development". Ars Orientalis. 40: 90. JSTOR 23075932.

- ^ Delbanco, Dawn Ho (1983). "The Romance of the Western Chamber: Min Qiji's Album in Cologne". Orientations. 40 (6): 13–15, 18, 20–23.

- ^ Hsu, Wen-Chin (2011). "Illustrations of Romance of the Western Chamber on Chinese Porcelains: Iconography, Style, and Development". Ars Orientalis. 40: 60–61. JSTOR 23075932.

- ^ Hsu, Wen-Chin (2011). "Illustrations of Romance of the Western Chamber on Chinese Porcelains: Iconography, Style, and Development". Ars Orientalis. 40: 43–46. JSTOR 23075932.

- ^ Hsu, Wen-Chin (2011). "Illustrations of Romance of the Western Chamber on Chinese Porcelains: Iconography, Style, and Development". Ars Orientalis. 40: 45. JSTOR 23075932.

- ^ Hsu, Wen-Chin (2011). "Illustrations of Romance of the Western Chamber on Chinese Porcelains: Iconography, Style, and Development". Ars Orientalis. 40: 41–42. JSTOR 23075932.

- ^ "The Story of the Western Wing." (Archive) University of California Press. Retrieved on December 8, 2013.

- ^ Crossley, Pamela Kyle; Rawski, Evelyn S. (Jun 1993). "A Profile of The Manchu Language in Ch'ing History". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 53 (1). Harvard-Yenching Institute: 94. doi:10.2307/2719468. JSTOR 2719468.

- ^ Merker, p. 242.

Further reading

[edit]- (in German) "Zu der Besprechung meines Buches "Das Westzimmer durch Prof. E. Haenisch in Asia Major VIII 1/2" (Archive) "Das Westzimmer." P. 563

External links

[edit]- Xi Xiang Ji at Project Gutenberg (in Chinese)

- Secret Edition of the Northern Western Wing Corrected by Mr. Zhang Shenzhi from the World Digital Library