Marian art in the Catholic Church

Mary has been one of the major subjects of Western art for centuries. There is an enormous quantity of Marian art in the Catholic Church, covering both devotional subjects such as the Virgin and Child and a range of narrative subjects from the Life of the Virgin, often arranged in cycles. Most medieval painters, and from the Reformation to about 1800 most from Catholic countries, have produced works, including old masters such as Michelangelo and Botticelli.[1]

Marian art forms part of the fabric of Catholic Marian culture through their emotional impact on her veneration. Images such as Our Lady of Guadalupe and the many artistic renditions of it as statues are not simply works of art but are a central element of the daily lives of the Mexican people.[2] Both Hidalgo and Zapata flew Guadalupan flags and depictions of the Virgin of Guadalupe continue to remain a key unifying element in the Mexican nation.[3] The study of Mary via the field of Mariology is thus inherently intertwined with Marian art.[4]

The body of teachings that constitute Catholic Mariology consist of four basic Marian dogmas: Perpetual virginity, Mother of God, Immaculate Conception and Assumption into Heaven, derived from Biblical scripture, the writings of the Church Fathers, and the traditions of the Church. Other influences on Marian art have been the Feast days of the Church, Marian apparitions, writings of the saints and popular devotions such as the rosary, the Stations of the Cross, or total consecration, and also papal initiatives, and Marian papal encyclicals and Apostolic Letters.

| Part of a series on the |

| Mariology of the Catholic Church |

|---|

|

|

|

Blending of art, theology and spirituality

[edit]

Art has been an integral element of Catholic identity since Late antiquity.[5] Medieval Catholicism cherished relics and pilgrimages to visit them were common. Churches and specific works of art were commissioned to honor the saints and the Virgin Mary has always been seen as the most powerful intercessor among all saints—her depictions being the subject of veneration among Catholics worldwide.[5]

Catholic Mariology does not simply consist of a set of theological writings, but also relies on the emotional impact of art, music and architecture. Catholic Marian music and Catholic Marian churches interact with Marian art as key components of Mariology, e.g. the construction of major Marian churches gives rise to major pieces of art for the decoration of the church.[6][7][8][9]

In the 16th century, Gabriele Paleotti's Discourse on Sacred and Profane Images became known as the "Catechism of images" for Catholics, given that it established key concepts for the use of images as a form of religious instruction and indoctrination via silent preaching (muta predicatio).[10][11] Paleotti's approach was implemented by his powerful contemporary Saint Charles Borromeo and his focus on "the transformation of Christian life through vision" and the "nonverbal rules of language" shaped the Catholic reinterpretations of the Virgin Mary in the 16th and 17th centuries and fostered and promoted Marian devotions such as the Rosary.[10][11]

An example of the interaction of Marian art, culture and churches is Salus Populi Romani, a key Marian icon in Rome at Santa Maria Maggiore, the earliest Marian church in Rome. The practice of crowning the images of Mary started at Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome by Pope Clement VIII in the 17th century.[12] In 1899 Eugenio Pacelli (later Pope Pius XII) said his first Holy Mass in front of it at the Santa Maria Maggiore. Fifty years later, he physically crowned this picture as part of the first Marian year in Church history, as he proclaimed the Queenship of Mary. The image was carried from Santa Maria Maggiore around Rome as part of the celebration of the Marian year and the proclamation of the Queenship of Mary.

Another example is Our Mother of Perpetual Help. Catholics have, for centuries, prayed before this icon, usually in reproductions, to intercede on their behalf to Christ.[13] Over the centuries, several churches dedicated to Our Mother of Perpetual Help have been constructed. Pope John Paul II held mass at the National Shrine of Our Mother of Perpetual Help in the Philippines where the devotion is very popular and many Catholic churches hold a Novena and Mass honoring it every Wednesday using a replica of the icon, which is also widely displayed in houses, buses and public transport in the Philippines.[14][15][16] Devotions to the icon have spread from the Philippines to the United States, and remain popular among Asian-Americans in California.[17][18] As recently as 1992, the song The Lady Who Wears Blue and Gold was composed in California and then performed at St. Alphonsus Liguori Church in Rome, where the icon resides. This illustrates how a medieval work of art can give rise to feast days, Cathedrals and Marian music.

The use of Marian art by Catholics worldwide accompanies specific forms of Marian devotion and spirituality. The widespread Catholic use of replicas of the statue of Our Lady of Lourdes emphasizes devotions to the Immaculate Conception and the Rosary, both reported in the Lourdes messages. To Catholics, the distinctive blue and white Lourdes statues are reminders of the emphasis of Lourdes on Rosary devotions and the millions of pilgrimages to the Rosary Basilica at Lourdes shows how Churches, devotions and art intertwine within Catholic culture. The Rosary remains the prayer of choice among Catholics who visit Lourdes or venerate the Lourdes statues worldwide.[19][20][21][22]

Historically, Marian art has not only impacted the image of Mary among Catholics, but that of Jesus. The early "Kyrios image" of Jesus as "the Lord and Master" was specially emphasized in the Pauline Epistles.[23][24][25] The 13th century depictions of the Nativity of Jesus in art and the Franciscan development of a "tender image of Jesus" via the construction of Nativity scenes changed that perception and was instrumental in portraying a softer image of Jesus that contrasted with the powerful and radiant image at the Transfiguration.[26] The emphasis on the humility of Jesus and the poverty of his birth depicted in Nativity art reinforced the image of God not as severe and punishing, but himself humble at birth and sacrificed at death.[27] As the tender joys of the Nativity were added to the agony of Crucifixion (as depicted in scenes such as Stabat Mater) a whole new range of approved religious emotions were ushered in via Marian art, with wide-ranging cultural impacts for centuries thereafter.[28][29][30]

The spread of devotions to the Virgin of Mercy are another example of the blending of art and devotions among Catholics. In the 12th century Cîteaux Abbey in France used the motif of the protective mantle of the Virgin Mary which shielded the kneeling abbots and abbesses. In the 13th century Caesarius of Heisterbach was also aware of this motif, which eventually led to the iconography of the Virgin of Mercy and an increased focused on the concept of Marian protection.[31] By the beginning of the 16th century, depictions of the Virgin of Mercy were among the preferred artistic items in households in the Paris area.[32] In the 18th century Saint Alphonsus Liguori attributed his own recovery from near death to a statue of the Virgin of Mercy brought to his bedside.[33]

In his apostolic letter Archicoenobium Casinense in 1913, Pope Pius X echoed the same sentiment regarding the blending of art, music and religion by comparing the artistic efforts of the Benedictine monks of the Beuron Art School (who had previously produced the "Life of the Virgin" series), to the revival of the Gregorian chant by the Benedictines of Solesmes Abbey and wrote, "...together with sacred music, this art proves itself to be a powerful aid to the liturgy".[34]

Diversity of Marian art

[edit]

Catholic Marian art has expressed a wide range of theological topics that relate to Mary, often in ways that are far from obvious, and whose meaning can only be recovered by detailed scholarly analysis. Entire books, academic theses or lengthy scholarly works have been written on various aspects of Marian art in general and on specific topics such as the Black Madonna, Our Lady of San Juan de los Lagos, Virgin of Mercy, Virgin of Ocotlán, or the Hortus conclusus and their doctrinal implications. [36][37][38][39][40]

Some of the leading Marian subjects include:

|

The tradition of Catholic Marian art has continued in the 21st century by artists such as Miguel Bejarano Moreno and Francisco Cárdenas Martínez.

Early veneration

[edit]

Early veneration of Mary is documented in the Catacombs of Rome. In the catacombs paintings show Mary with Jesus. More unusual and indicating the burial ground of Saint Peter, was the fact that excavations in the crypt of Saint Peter discovered a very early fresco of Mary together with Saint Peter.[41] The Roman Priscilla catacombs contain the known oldest Marian paintings, dating from the middle of the second century.[42] In one, Mary is shown with the infant Jesus on her lap. The Priscilla catacomb also includes the oldest known fresco of the Annunciation, dating to the 4th century.[43]

After the Edict of Milan in 313 Christians were permitted to worship and build churches openly. The generous and systematic patronage of Roman Emperor Constantine I changed the fortunes of the Christian church, and resulted in both architectural and artistic development.[44] The veneration of Mary became public and Marian art flourished. Some of the earliest Marian churches in Rome date to the 5th century, such as Santa Maria in Trastevere, Santa Maria Antiqua and Santa Maria Maggiore, and these churches were in turn decorated with significant works of art through the centuries.[45][46] The interaction of Marian art and church construction thus influenced the development of Marian art.[47]

The Virgin Mary has since become a major subject of Western Art. Masters such as Michelangelo, Botticelli, Leonardo da Vinci, Giotto, Duccio and others produced masterpieces with Marian themes.

Mother of God

[edit]

Mary's status as the Mother of God was not made clear in the Gospels and Pauline Epistles but the theological implications of this were defined and confirmed by the Council of Ephesus (431). Different aspects of Mary's position as mother have been the subject of a large number of works of Catholic art.

There was a great expansion of the cult of Mary after the Council of Ephesus in 431, when her status as Theotokos was confirmed; this had been a subject of some controversy until then, though mainly for reasons to do with arguments over the nature of Christ. In mosaics in Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome, dating from 432 to 40, just after the council, she is not yet shown with a halo, and she is also not shown in Nativity scenes at this date, though she is included in the Adoration of the Magi.[46][48]

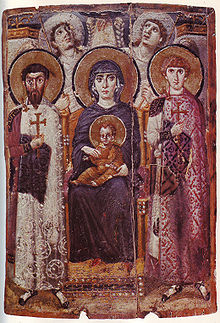

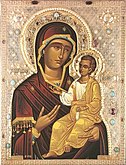

By the next century the iconic depiction of the Virgin enthroned carrying the infant Christ was established, as in the example from the only group of icons surviving from this period, at Saint Catherine's Monastery in Egypt. This type of depiction, with subtly changing differences of emphasis, has remained the mainstay of depictions of Mary to the present day. The image at Mount Sinai succeeds in combining two aspects of Mary described in the Magnificat, her humility and her exaltation above other humans.

At this period the iconography of the Nativity was taking the form, centred on Mary, that it has retained up to the present day in Eastern Orthodoxy, and on which Western depictions remained based until the High Middle Ages. Other narrative scenes for Byzantine cycles on the Life of the Virgin were being evolved, relying on apocryphal sources to fill in her life before the Annunciation to Mary. By this time the political and economic collapse of the Western Roman Empire meant that the Western, Latin, church was unable to compete in the development of such sophisticated iconography, and relied heavily on Byzantine developments.

The earliest surviving image in a Western illuminated manuscript of the Madonna and Child comes from the Book of Kells of about 800 and, though magnificently decorated in the style of Insular art, the drawing of the figures can only be described as rather crude compared to Byzantine work of the period. This was in fact an unusual inclusion in a Gospel book, and images of the Virgin were slow to appear in large numbers in manuscript art until the book of hours was devised in the 13th century.

Nativity of Jesus

[edit]

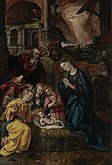

The Nativity of Jesus has been a major subject of Christian art since the early 4th century. It has been depicted in many different media, both pictorial and sculptural. Pictorial forms include murals, panel paintings, manuscript illuminations, stained glass windows and oil paintings. The earliest representations of the Nativity itself are very simple, just showing the infant, tightly wrapped, lying near the ground in a trough or wicker basket.

A new form of the image, which from the rare early versions seems to have been formulated in 6th-century Palestine, was to set the essential form of Eastern Orthodox images down to the present day. The setting is now a cave – or rather the specific Cave of the Nativity in Bethlehem, already underneath the Church of the Nativity, and well-established as a place of pilgrimage, with the approval of the Church.

Western artists adopted many of the Byzantine iconographic elements, but preferred the scriptural stable to the cave, though Duccio's Byzantine-influenced Maestà version tries to have both. During the Gothic period, in the North earlier than in Italy, increasing closeness between mother and child develops, and Mary begins to hold her baby, or he looks over to her. Suckling is very unusual, but is sometimes shown.

The image in later medieval Northern Europe was often influenced by the vision of the Nativity of Saint Bridget of Sweden (1303–1373), a very popular mystic. Shortly before her death, she described a vision of the infant Jesus as lying on the ground, and emitting light himself.

From the 15th century onwards, the Adoration of the Magi increasingly became a more common depiction than the Nativity proper. From the 16th century plain Nativities with just the Holy Family, become a clear minority, although Caravaggio led a return to a more realistic treatment of the Adoration of the Shepherds.

The perpetual character of Mary's virginity, namely that she was a virgin all her life and not only at her virginal conception of Jesus Christ at the Annunciation (that she was a virgin before, during and after giving birth to him) is alluded to in some forms of Nativity art: Salome, who according to the story in the 2nd-century Nativity of Mary[49] received physical proof that Mary remained a virgin even in giving birth to Jesus, is found in many depictions of the Nativity of Jesus in art.[50]

Madonna

[edit]

The depiction of the Madonna has roots in ancient pictorial and sculptural traditions that informed the earliest Christian communities throughout Europe, Northern Africa and the Middle East. Important to Italian tradition are Byzantine icons, especially those created in Constantinople (Istanbul), the capital of the longest, enduring medieval civilization whose icons, such as the Hodegetria, participated in civic life and were celebrated for their miraculous properties. Western depictions remained heavily dependent on Byzantine types until at least the 13th century. In the late Middle Ages, the Cretan school, under Venetian rule, was the source of great numbers of icons exported to the West, and the artists there could adapt their style to Western iconography when required.

In the Romanesque period free-standing statues, typically about half life-size, of the enthroned Madonna and Child were an original Western development, since monumental sculpture was forbidden by Orthodoxy. The Golden Madonna of Essen of c. 980 is one of the earliest of these, made of gold applied to a wooden core, and still the subject of considerable local veneration, as is the 12th century Virgin of Montserrat in Catalonia, a more developed treatment.

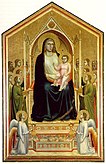

With the growth of monumental panel painting in Italy during the 12th and 13th centuries, this type was frequently painted at the image of the Madonna gains prominence outside of Rome, especially throughout Tuscany. While members of the mendicant orders of the Franciscan and Dominican Orders are some of the first to commission panels representing this subject matter, such works quickly became popular in monasteries, parish churches, and later homes. Some images of the Madonna were paid for by lay organizations called confraternities, who met to sing praises of the Virgin in chapels found within the newly reconstructed, spacious churches that were sometimes dedicated to her.

Some key Madonnas

[edit]

A number of Madonna paintings and statues have gathered a following as important religious icons and noteworthy works of art in various regions of the world.

Some Madonnas are known by a general name and concept rendered or depicted by various artists. For instance, Our Lady of Sorrows is the patron saint of several countries such as Slovakia and Philippines. It is represented as the Virgin Mary wounded by seven swords in her heart, a reference to the prophecy of Simeon at the Presentation of Jesus. Our Lady of Sorrows, Queen of Poland located in the Sanctuary of Our Lady of Licheń (Poland's largest church) is an important icon in Poland. The term Our Lady of Sorrows is also used in other contexts, without a Madonna, e.g. for Our Lady of Kibeho apparitions.

Some Madonnas become the subject of widespread devotion, and the Marian shrines dedicated to them attract millions of pilgrims per year. An example is Our Lady of Aparecida in Brazil, whose shrine is surpassed in size only by Saint Peter's Basilica in Vatican City, and receives more pilgrims per year than any other Catholic Marian church in the world.[51]

Latin America

[edit]There is a rich tradition of building statues of the Madonna in South America, a sampling of which is shown in the galleries section of this article. The South American tradition of Marian art dates back to the 16th century, with the Virgin of Copacabana gaining fame in 1582.[52] Some noteworthy examples are:

- Our Lady of San Juan de los Lagos is located in the small town of San Juan de los Lagos in Mexico. It is the second most visited pilgrimage shrine in Mexico, after Our Lady of Guadalupe.

- The Virgin of Ocotlán is a statue of the Virgin Mary in Ocotlán, Tlaxcala, Mexico.

- Our Lady of Navigators is a highly venerated Madonna in Brazil. The devotion started by the 15th century Portuguese navigators, praying for a safe return to their homes and then spread in Brazil.

Images of, and devotions to, Madonnas such as Our Lady of San Juan de los Lagos have spread from Mexico to the United States.[53][54]

Italy and Spain

[edit]

- The Madonna of humility by Domenico di Bartolo, 1433, is considered one of the most innovative devotional images from the early Renaissance.[35]

- Raphael's Sistine Madonna. The painting, originally commissioned for the church of San Sisto, Piacenza, is now at the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister in Dresden (Germany). It is considered a key example of high Renaissance art.

- Madonna della Strada at the Church of the Gesu in Rome is a historic icon and the patron saint of the Jesuits

- The Madonna statue at the altar of Milan Cathedral is an outstanding example of Baroque Marian art

- Murillo's Dolorosa Madonna in Seville, Spain is a key example of a sorrowful Madonna

- Madonna of the Pillar at Zaragoza, Spain is a highly venerated statue based on a legendary vision of Saint James the Greater.

- The Virgin of Montserrat at the Santa María de Montserrat monastery in Spain is a highly venerated statue and the patron saint of Catalonia.

Central and Northern Europe

[edit]- The Black Madonna of Częstochowa is Poland's holiest relic, and one of the country's national symbols.

- Dutch painter Jan van Eyck's Lucca Madonna at the Städel Museum in Frankfurt is a good example of iconography where the Virgin Mary is portrayed as the Throne of Wisdom, with Jesus sitting on her lap.

- Michelangelo's statue of the Virgin Mary and a standing Jesus known as the Madonna of Bruges at the Church of Our Lady, Bruges, Belgium shares some similarities with his Pietà which was completed sometime earlier.

- The 1898 Refugium Peccatorum Madonna by the Italian artist Luigi Crosio has gathered significant popular following in central Europe and has since been called the Mother Thrice Admirable Madonna, as a symbol of the Schoenstatt Movement.[55][56][57]

Mary in the Life of Christ

[edit]

Scenes of Mary and Jesus together fall into two main groups: those with an infant Jesus, and those from the last period of his life. After the episodes of the Nativity, there are a number of further narrative scenes of Mary and the infant Jesus together which are often depicted: the Circumcision of Christ, Presentation of Jesus at the Temple, Flight into Egypt, and less specific scenes of Mary and Jesus with his cousin John the Baptist, sometimes with John's mother Elizabeth. Leonardo da Vinci's Virgin of the Rocks is a famous example. Gatherings of the whole extended family of Jesus form a subject known as the Holy Kinship, popular in the Northern Renaissance. Mary appears in the background of the only incident in the Gospels from the later childhood of Jesus, the Finding in the Temple.

Mary is then usually absent from scenes of the period of Christ's life between his Baptism and his Passion, except for the Wedding at Cana, where she is placed in the Gospels. A non-scriptural subject of Christ taking leave of his Mother (before going to Jerusalem at the start of his Passion) was often painted in 15th- and early 16th-century Germany. Mary is placed at the Crucifixion of Jesus by the Gospels, and is almost invariably shown, with Saint John the Evangelist, in fully depicted works, as well as often being shown in the background of earlier scenes of the Passion of Christ. The rood cross common in medieval Western churches had statues of Mary and John flanking a central crucifix. Mary is shown as present at the Deposition of Christ and his Entombment; in the late Middle Ages the Pietà emerged in Germany as a separate subject, especially in sculpture. Mary is also included, though this is not mentioned in any of the scriptural accounts, in depictions of the Ascension of Jesus. After the Ascension, she is the centrally-placed figure in depictions of Pentecost, which is her latest appearance in the Gospels.

The main scenes above, showing incidents celebrated as feast days by the church, formed part of cycles of the Life of the Virgin (though the selection of scenes in these varied considerably), as well as the Life of Christ.

Perpetual virginity

[edit]

The dogma of the perpetual virginity of Mary is the earliest of the four Marian dogmas and Catholic liturgy has repeatedly referred to Mary as "ever virgin" for centuries.[58][59] The dogma means that Mary was a virgin before, during and after giving birth to Jesus Christ. The 2nd-century work originally known as the Nativity of Mary pays special attention to Mary's virginity.[60]

This dogma is often represented in Catholic art in terms of the annunciation to Mary by the Archangel Gabriel that she would conceive a child to be born the Son of God, and in Nativity scenes that include the figure of Salome. The Annunciation is one of the most frequently depicted scenes in Western art.[61] Annunciation scenes also amount to the most frequent appearances of Gabriel in medieval art.[62] The depiction of Joseph turning away in some Nativity scenes is a discreet reference to the fatherhood of the Holy Spirit, and the doctrine of Virgin Birth.[63]

Frescos depicting this scene have appeared in Catholic Marian churches for centuries and it has been a topic addressed by many artists in multiple media, ranging from stained glass to mosaic, to relief, to sculpture to oil painting.[64] The oldest fresco of the annunciation is a 4th-century depiction in the Catacomb of Priscilla in Rome.[65] In most (but not all) Catholic, and indeed Western, depictions Gabriel is shown on the left, while in the Eastern Church he is more often depicted on the right.[66]

It has been one of the most frequent subjects of Christian art particularly during the Middle Ages and Renaissance. The figures of the Virgin Mary and the Archangel Gabriel, being emblematic of purity and grace, were favorite subjects of many painters such as Sandro Botticelli, Leonardo da Vinci, Caravaggio, Duccio and Murillo among others. In many depictions the angel may be holding a lily, symbolic of Mary's virginity.[67] The mosaics of Pietro Cavallini in Santa Maria in Trastevere in Rome (1291), the frescos of Giotto in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua (1303), Domenico Ghirlandaio's fresco at the church of Santa Maria Novella in Florence (1486) and Donatello's gilded sculpture at the church of Santa Croce, Florence (1435) are famous examples.

The natural composition of the scene, consisting of two figures facing each other, also made it suitable for decorated arches above doorways.

Immaculate Conception

[edit]

Given that up to the 13th century a series of saints including Bernard of Clairvaux, Bonaventure, Thomas Aquinas, and the Dominicans in general had either opposed or questioned this doctrine, Catholic art on the subject mostly dates to periods after the 15th century and is absent from Renaissance art. But with support from popular opinion, the Franciscans and theologians such as Duns Scotus, the popularity of the doctrine increased and a feast-day for it was promoted.

Pope Pius V, the Dominican Pope who in 1570 established the Tridentine Mass, included the feast (but without the adjective "Immaculate") in the Tridentine calendar, but suppressed the existing special Mass for the feast, directing that the Mass for the Nativity of Mary (with the word "Nativity" replaced by "Conception") be used instead.[68] Part of that earlier Mass was revived in the Mass that Pope Pius IX ordered to be used on the feast and that is still in use.[69]

In the 16th century there was a widespread intellectual fashion for emblems in both religious and secular contexts. These consisted of a visual representation of the symbol (pictura) and usually a Latin motto; frequently an explanatory epigram was added. Emblem books were very popular.[70]

Drawing on the emblem tradition, Francisco Pacheco established an iconography that Spanish artists such as Bartolomé Murillo (especially), Diego Velázquez (Pacheco's son-in-law) and others adopted, with variations, and then spread to the rest of Europe, since when it has remained the usual depiction. Additional imagery may include clouds, a golden light, and cherubs. In some paintings the cherubim are holding lilies and roses, flowers often associated with Mary.

The dogmatic definition of Immaculate Conception was performed by Pope Pius IX in his Apostolic Constitution Ineffabilis Deus, in 1854.

Depiction of the Immaculate Conception

[edit]

Many artists in the 15th century faced the problem of how to depict an abstract idea such as the Immaculate Conception, and the problem was not fully solved for 150 years.

Since a key Scriptural text pointed to in support of the doctrine was "Tota pulchra es...", "Thou art all fair, my love; there is no spot in thee", verse 4.7 from the Song of Solomon,[71] a number of symbolic objects drawn from the imagery of the Song, and often already associated with the Annunciation and the Perpetual Virginity, were combined in versions of the Hortus conclusus ("enclosed garden") subject. This gave a rather cluttered subject, and usually was impossible to combine with correct perspective, so never caught on outside Germany and the Low Countries. Piero di Cosimo was among those artists who tried new solutions, but none of these became generally adopted so that the subject would be immediately recognisable to the faithful.

The definitive iconography for the Immaculate Conception, drawing on the emblem tradition, seems to have been established by the master and then father-in-law of Diego Velázquez, the painter and theorist Francisco Pacheco (1564–1644), to whom the Inquisition in Seville also contracted the approval of new images. He described his iconography in his Art of Painting (Arte de la Pintura, published posthumously in 1649):

"The version that I follow is the one that is closest to the holy revelation of the Evangelist and approved by the Catholic Church on the authority of the sacred and holy interpreters... In this loveliest of mysteries Our Lady should be painted as a beautiful young girl, 12 or 13 years old, in the flower of her youth... And thus she is praised by the Husband: tota pulchra es amica mea, a text that is always written in this painting. She should be painted wearing a white tunic and a blue mantle... She is surrounded by the sun, an oval sun of white and ochre, which sweetly blends into the sky. Rays of light emanate from her head, around which is a ring of twelve stars. An imperial crown adorns her head, without, however, hiding the stars. Under her feet is the moon. Although it is a solid globe, I take the liberty of making it transparent so that the landscape shows through."[72][73]

Assumption of Mary

[edit]

The Catholic doctrine of the Assumption of Mary into Heaven states that Mary was transported into Heaven with her body and soul united. Although the Assumption was only officially declared a dogma by Pope Pius XII in his Apostolic Constitution Munificentissimus Deus in 1950, its roots in Catholic culture and art go back many centuries. While Pope Pius XII deliberately left open the question of whether Mary died before her Assumption, the more common teaching of the early Fathers is that she did.[74][75]

An early supporter of the Assumption was Saint John of Damascus (676–794), a Doctor of the Church who is often called the Doctor of the Assumption.[76] Saint John was not only interested in the Assumption, but also supported the use of holy images in response to the edict by the Byzantine Emperor Leo III, banning the worship or exhibition of holy images.[77] He wrote: "On this day the sacred and life-filled ark of the living God, she who conceived her Creator in her womb, rests in the Temple of the Lord that is not made with hands. David, her ancestor, leaps, and with him the angels lead the dance."

The Eastern Church held the feast of the Assumption as early as the second half of the 6th century, and Pope Sergius I (687–701) ordered its observance in Rome.[78]

The Orthodox tradition is clear that Mary died normally, before being bodily assumed. The Orthodox term for the death is the Dormition of the Virgin. Byzantine depictions of this were the basis for Western images, the subject being known as the Death of the Virgin in the West. As the nature of the Assumption became controversial during the High Middle Ages, the subject was often avoided, but depiction continued to be common until the Reformation. The last major Catholic depiction is Caravaggio's Death of the Virgin of 1606.

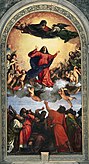

Meanwhile, depictions of the Assumption had been becoming more frequent during the late Middle Ages, with the Gothic Siennese school a particular source. By the 16th century they had become the norm, initially in Italy, and then elsewhere. They were sometimes combined with the Coronation of the Virgin, as the Trinity waited in the clouds. The subject was very suited to Baroque treatment.

Queen of Heaven

[edit]

The Catholic teaching that Mary is far above all other creatures in dignity, and after Jesus Christ possesses primacy over all goes back to the early church. Saint Sophronius said: "You have surpassed every creature" and Saint Germain of Paris (496–576) stated: "Your honor and dignity surpass the whole of creation; your greatness places you above the angels." Saint John of Damascus went further: "Limitless is the difference between God's servants and His Mother."[79][80]

The feast of the Queenship of Mary was only formally established in 1954 by Pope Pius XII in his encyclical Ad Caeli Reginam. Pius XII also declared the first Marian year and a number of Catholic Church rededications took place, e.g. the 1955 rededication of the church of Saint James the Great in Montreal with the new title Mary, Queen of the World Cathedral a title proclaimed by Pius XII.

Yet, long before 1954 the Coronation of the Virgin had been the subject of a good number of artistic works. Some of these paintings built on the third phase of the Assumption of Mary in which following her Assumption, she is crowned as the Queen of Heaven.

Apparitions

[edit]

Catholic devotion to Mary has at times been driven by religious experiences and visions of simple and modest individuals (in many cases children) on remote hilltops which in time have created strong emotions among large numbers of Catholics. Examples include Saint Juan Diego in 1531 as Our Lady of Guadalupe, Saint Bernadette Soubirous as Our Lady of Lourdes in 1858 and Lucia dos Santos, Jacinta Marto and Francisco Marto as Our Lady of Fatima in 1917.[82]

Although every year over five million pilgrims visit Lourdes and Guadalupe each, the volume of Catholic art to accompany this enthusiasm has been essentially restricted to popular images. Hence although apparitions have resulted in the construction of very large Marian churches at Lourdes and Guadalupe they have not so far had a similar impact on Marian art. Yet images such as Our Lady of Guadalupe and the artistic renditions of it as statues are not simply works of art but are a central elements of the daily lives of the Mexican people.[2] Both Miguel Hidalgo and Emiliano Zapata flew Guadalupan flags as their protector, and Zapata's men wore the Guadalupan image around their necks and on their sombreros.[83][84] Depictions of the Virgin of Guadalupe continue to remain a key unifying element in the Mexican nation, and as the main national symbol of Mexico.[3]

Apparition-based art is at times considered miraculous by Catholics. Replicas of the distinctive blue and white statue of Our Lady of Lourdes are widely used by Catholics in devotions, and small grottos with it are built in houses and Catholic neighborhoods worldwide and are the subject of prayers and petitions.[85] In Ad Caeli Reginam, Pope Pius XII called the statue of Our Lady of Fatima "miraculous" and Pope John Paul II attributed his survival after the 1981 assassination attempt to its intercession, donating one of the bullets that wounded him to the Sanctuary in Fatima.[81][86]

Distinguishing characteristics

[edit]The Catholic approach to Marian art is quite distinct from the way other Christians (such as the Protestant and the Eastern Orthodox) treat the depictions of the Virgin Mary. From the very beginning of the Protestant Reformation its leaders expressed their discomfort with the depictions of saints in general. While over time a Protestant tradition of art developed, the depictions of the Virgin Mary within it have remained minimal, given that most Protestants reject Marian veneration and view it as a Catholic excess.[87][88][89]

Unlike the majority of the Protestants, the Eastern Orthodox Church venerates Marian images, but in a different manner and with a different emphasis from the Catholic tradition. While statues of the Virgin Mary abound in Catholic churches, there are specific prohibitions against all three-dimensional representations (of Mary or any other any saints) within the Orthodox Church, for they are regarded as remnants of pagan idolatry. Hence the Orthodox only produce and venerate two-dimensional images.[90][91][92][93]

Catholic Marian images are almost entirely devotional depictions and do not have an official standing within liturgy, but Eastern icons are an inherent part of Orthodox liturgy. In fact, there is a three way, carefully coordinated interplay of prayers, icons and hymns to Mary within Orthodox liturgy, at times with specific feasts that relate to the Theotokos icons and the Akathists.[90][93][94]

While there is a tradition for the best known Western artists from Duccio to Titian to depict the Virgin Mary, most painters of Eastern Orthodox icons have remained anonymous for the production of an icon is not viewed as a "work of art" but as a "sacred craft" practiced and perfected in monasteries.[90] To some Eastern Orthodox the natural looking Renaissance depictions used in Catholic art are not conducive to meditation, for they lack the kenosis needed for Orthodox contemplation. The rich background representation of flowers or gardens found in Catholic art are not present in Orthodox depictions whose primary focus is the Theotokos, often with the Child Jesus.[95][96] Apparition-based images such as the statues of the Our Lady of Lourdes accentuate the differences in that they are based on apparitions that are purely Catholic, as well as being three-dimensional representations. And the presence of Sacramentals such as the Rosary and the Brown Scapular on the statues of Our Lady of Fatima emphasize a totally Catholic form of Marian art.

Apart from stylistic issues, significant doctrinal differences separate Catholic Marian art from other Christian approaches. Three examples are the depictions that involve the Immaculate Conception, Queen of Heaven and the Assumption of Mary. Given that the Immaculate Conception is a mostly Catholic doctrine, its depictions within other Christian traditions remain rare.[97] The same applies to Queen of Heaven, for long an element of Catholic tradition (and eventually the subject of the encyclical Ad Caeli Reginam) but its representation within themes such as the Coronation of the Virgin continue to remain mostly Catholic.[86] While the Eastern Orthodox support the Dormition of the Theotokos, they do not support the Catholic doctrines of the Assumption of Mary and hence their depictions of the dormition are distinct and the Virgin Mary is usually shown sleeping surrounded by saints, while Catholic depictions often show Mary rising to Heaven.[93][98]

Galleries of Marian art

[edit]- Perpetual virginity

-

Annunciation by Mariotto Albertinelli, 15th century

-

Annunciation by Murillo, 1655

-

Philippe de Champaigne, 1644

-

Annunciation by Pietro Perugino, 1489

-

Cestello Annunciation by Botticelli, 1490

-

Francesco Albani Annunciation The Hermitage

-

Mikhail Nesterov, Russia, 19th century

- Birth of Christ

-

Adoration of the Magi, ivory, 15th century

-

Marten de Vos, 1577

-

Lorenzo Lotto, 1523

-

Pietro Perugino, 15th century

-

Pedro Berruguete, 15th century

-

Giorgione, c1507

-

Gregorio Fernández, 1614

-

Gauguin, 1896

- Adoration of the shepherds

-

Caravaggio, 16th century

-

Bronzino, 16th century

-

Guido Reni, 1630–1642

-

Gaudenzio Ferrari c1533

-

Gerard van Honthorst, 1622

-

Domenico Ghirlandaio, 1485

-

Giorgione, 1510

- Adoration of the Magi

-

Rembrandt, 1632

-

Rubens, 1634

-

Botticelli, 1475

-

Murillo, 17th century

-

Gentile da Fabriano, 1423

-

Jacopo da Ponte, 1563–1564

-

Diego Velázquez, 1619

Pre 15th century

[edit]- Pre 15th century

-

Virgin, 6th century, St. Catherine Monastery

-

Vatopedi, Mount Athos, Greece, pre-870

-

Russian Theotokos icon, 10th century

-

Madonna, Cimabue 13th century

-

Madonna and Angels, Duccio, 1282

-

Madonna by Giotto, c1300

-

Giacomo di Mino, 1342

-

Naddo Ceccarelli, 1347

15-16th century

[edit]- 15-16th century

-

Taddeo di Bartolo 1400–1405

-

Madonna and Child, Filippo Lippi 1440–1445

-

Madonna, with God the Father in evidence, Filippo Lippi, 1459

-

Benois Madonna, Leonardo da Vinci, 1475

-

Magnificat Madonna, Botticelli, 1481

-

Madonna and five angels, Botticelli, c1485–1490

-

The Glorification of the Virgin, Geertgen tot Sint Jans, c. 1490–1495

-

Madonna del Granduca, Raphael, 1505

-

Tempi Madonna, Raphael, 1508

-

Titian, 1520

Post 16th century

[edit]- Post 16th century

-

Madonna and Child by Sassoferrato, 17th century

-

Our Lady of Rokitno, Poland, 1671

-

Madonna, Pompeo Batoni, 1742

-

Virgin of the Host, Dominique Ingres, 1852

-

Franz Ittenbach, 1855

-

Queen of the Angels, Bouguereau, 1900

- Pre 15th century

-

Fontignano. Pietro Perugino, 1522

- Madonna statues

-

Assumption statue, Attard, Malta

-

Our Lady of Navigators, Porto Alegre, Brazil

-

Our Lady of Aparecida, patron saint of Brazil

-

Our Lady of Saúde, Portugal

-

Our Lady of Sorrows in Warfhuizen, dressed for October

-

Golden Madonna of Essen, Essen, Germany

-

Virgen de los Ángeles, Costa Rica

-

Assumption statue, Għaxaq, Malta, 1808

-

Baroque Madonna Altar at the Milan Cathedral

Mary in the Life of Christ

[edit]- Mary in the Life of Christ

-

Rubens, Lamentation 1614/1615

-

Christ and Mary, mosaic, Chora Church, 16th century

-

Christ taking leave of his mother, Correggio, 1517–1518

-

Deposition of Christ, Regnault, 1789

-

Michelangelo's Pietà, 1498

-

Pietro Lorenzetti, Assisi Basilica, 1310–1329

- Immaculate conception

-

Murillo Immaculate Conception, 1650

-

Murillo Immaculate Conception, 1678

-

Velázquez Immaculate Conception, 1618

-

di Cosimo Immaculate Conception, 1505

-

Zurbarán Immaculate Conception, 1630

-

Carlo Maratta, 1689

-

Statue, Porto Alegre, Brazil, 19th century

-

Gregorio Fernández, 17th century

- Assumption

-

Andrea Mantegna Dormition 1461

-

Rubens Assumption, 1626

-

Titian Assumption, 1516

-

Mateo Cerezo Assumption, 1650

-

Guercino Assumption, 1655

-

Andrea del Sarto Assumption, 1526

-

Rubens Assumption of the Virgin, 17th century

-

Charles Le Brun, 1835

- Queen of Heaven

-

Martino di Bartolomeo, 1400

-

Crowning of the Virgin by Rubens, 17th century

-

Velázquez, Crowning of the Virgin, 1645

-

Gregorio di Cecco Enthroned Madonna

-

Giacomo di Mino, 1340–1350

-

Raphael, 1502–1504

-

Pietro Perugino, 1504

-

Giulio Cesare Procaccini, 17th century

- Apparitions

-

The Vision of St. Bernard by Fra Bartolommeo c. 1504

-

Apparition to St. Hyacinth by Lodovico Carracci 1594

-

Eternal Father painting the Virgin of Guadalupe anonymous, 18th century

-

Statue of Our Lady of Lourdes, Lourdes, France

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Timothy Verdon, 2006, Mary in Western Art ISBN 978-0-9712981-9-4

- ^ a b A History of Modern Latin America by Teresa A. Meade, 2009 ISBN 1-4051-2051-7 p. 45

- ^ a b The Virgin of Guadalupe by Maxwell E. Johnson 2003 ISBN 0-7425-2284-9 pp. 41–43

- ^ Caroline Ebertshauser et al. 1998 Mary: Art, Culture, and Religion through the Ages ISBN 978-0-8245-1760-1

- ^ a b Distinctively Catholic: an exploration of Catholic identity by Daniel Donovan 1997 ISBN 0-8091-3750-X pp. 96–98

- ^ Janusz Rosikon, 2001, The Madonnas of Europe: Pilgrimages to the Great Marian Shrines ISBN 978-0-89870-849-3

- ^ Edel 2006, Madonna: Sacred Art And Holy Music ISBN 9783937406404

- ^ University of Dayton Marian Music https://udayton.edu/imri/mary/b/birth-of-mary-meditation-and-illustrations.php

- ^ Peter Mullen Shrines of Our Lady ISBN 978-0-312-19503-8

- ^ a b The Mystery of the Rosary: Marian Devotion and the Reinvention of Catholicism by Nathan Mitchell 2009 ISBN 0-8147-9591-9 pp. 37–42

- ^ a b The road from Eden: studies in Christianity and culture by John Barber 2008 ISBN 1-933146-34-6 p. 288

- ^ Catholic encyclopedia

- ^ Ann Ball, 2003 Encyclopedia of Catholic Devotions and Practices ISBN 0-87973-910-X pp. 431–433

- ^ Vatican website: Pope John Paul II in the Philippines

- ^ Culture and customs of the Philippines by Paul A. Rodell 2001 ISBN 0-313-30415-7 p. 58

- ^ Relations between religions and cultures in Southeast Asia by Donny Gahral Adian, Gadis Arivia 2009 ISBN 1-56518-250-2 p. 129

- ^ Asian American religions by Tony Carnes, Fenggang Yang 2004 ISBN 0-8147-1630-X p. 355

- ^ Religion at the corner of bliss and nirvana by Lois Ann Lorentzen 2009 ISBN 0-8223-4547-1 pp. 278–280

- ^ The encyclopedia of Christianity, Volume 3 by Erwin Fahlbusch, Geoffrey William Bromiley 2003 ISBN 90-04-12654-6 p. 339

- ^ Our Sunday Visitor's Catholic Almanac by Matthew Bunson 2008 ISBN 1-59276-441-X p. 123

- ^ The Mystery of the Rosary by Nathan Mitchell 2009 ISBN 0-8147-9591-9 p. 193

- ^ China's Catholics by Richard Madsen 1998 ISBN 0-520-21326-2 pp. 6–7

- ^ Mercer dictionary of the Bible by Watson E. Mills, Roger Aubrey Bullard 1998 ISBN 0-86554-373-9 pp. 520–525

- ^ Lord Jesus Christ: Devotion to Jesus in Earliest Christianity by Larry W. Hurtado 2005 ISBN 0-8028-3167-2 pp. 113, 179

- ^ II Corinthians: a commentary by Frank J. Matera 2003 ISBN 0-664-22117-3 pp. 11–13

- ^ The image of St Francis by Rosalind B. Brooke 2006 ISBN 0-521-78291-0 pp. 183–184

- ^ The tradition of Catholic prayer by Christian Raab, Harry Hagan, St. Meinrad Archabbey 2007 ISBN 0-8146-3184-3 pp. 86–87

- ^ The vitality of the Christian tradition by George Finger Thomas 1944 ISBN 0-8369-2378-2 pp. 110–112

- ^ La vida sacra: contemporary Hispanic sacramental theology by James L. Empereur, Eduardo Fernández 2006 ISBN 0-7425-5157-1 pp. 3–5

- ^ Philippines by Lily Rose R. Tope, Detch P. Nonan-Mercado 2005 ISBN 0-7614-1475-4 p. 109

- ^ Arthur Calkins, Marian Consecration and Entrustment in Burke, Raymond L.; et al. (2008) Mariology: A Guide for Priests, Deacons, Seminarians, and Consecrated Persons ISBN 978-1-57918-355-4 pp. 725–737

- ^ Life in Renaissance France by Lucien Febvre 1979 ISBN 0-674-53180-9 p. 145

- ^ Saint Alphonsus Liguori by Saint Alfonso Maria de' Liguori, Richard Paul Blakeney 1852 p. 20

- ^ Acta Apostolicae Sedis 5, 1913, pp. 113–117

- ^ a b Art and music in the early modern period by Franca Trinchieri Camiz, Katherine A. McIver ISBN 0-7546-0689-9 p. 15 [1]

- ^ Roten S.M., Johann G., "Birth of Mary: Meditation and Illustration", International Marian Research Institute, University of Dayton

- ^ The Madonna della Misericordia in the Italian Renaissance by Carol McCall Rand, 1987, Thesis, Virginia Commonwealth University

- ^ Virgen de San Juan Shrine, by Bonnie Robertson, 1980 ASIN: B0021ZHECE

- ^ Luis Nava Rodríguez, 1975 Historia de Nuestra Senora de Ocotlan Tlaxcala: Editoria de periodicos "La Prensa", MLCS 98/02238

- ^ The énclosed garden: history and development of the hortus conclusus by Rob Aben, Saskia de Wit 1999 ISBN 90-6450-349-4

- ^ M Guarducci Maria nelle epigrafi paleocristiane di Roma 1963, 248

- ^ I Daoust, Marie dans les catacombes, in "Esprit et Vie", n. 91, 1983.

- ^ The Annunciation To Mary by Eugene LaVerdiere 2007 ISBN 1568545576 page 29

- ^ Early Christian Art and Architecture by R. L. P. Milburn (Feb 1991) ISBN 0520074122 Univ California Press page 303

- ^ Image and Relic: Mediating the Sacred in Early Medieval Rome by Erik Thun 2003 ISBN 8882652173 pages 33-35

- ^ a b Mary in Western Art by Timothy Verdon 2005 ISBN 097129819X pages 37-40

- ^ Michael Rose, 2004, In Tiers of Glory: The Organic Development of Catholic Church Architecture through the Ages Mesa Folio editions, ISBN 0967637120 pages 9-12

- ^ Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of World Religions 2000 ISBN 0877790442 page 408

- ^ Infancy Gospel of James, chapter 20 Archived 2008-06-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Encyclopedia of Comparative Iconography by Helene E. Roberts 1998 ISBN 1-57958-009-2 p. 904

- ^ Religions of the World by J. Gordon Melton, Martin Baumann 2003 ISBN 1576072231 pages 308-309

- ^ Art and architecture of viceregal Latin America, 1521–1821 by Kelly Donahue-Wallace 2008 ISBN 0826334598

- ^ Mapping the Catholic cultural landscape by Richard Fossey 2004 ISBN 0-7425-3184-8 p. 78

- ^ Globalizing the sacred: religion across the Americas by Manuel A. Vásquez, Marie F. Marquardt 2003 ISBN 0-8135-3285-X p. 74

- ^ Schoenstatt website "Father's Shepherds". Schoenstatt Movement. August 14, 2009. Archived from the original on 2009-10-10. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ Research on Luigi Crosio Archived 2012-06-29 at archive.today

- ^ University of Dayton Archived 2012-05-09 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Marian Dogmas at University of Dayton http://campus.udayton.edu/mary/mariandogmas.html

- ^ Divine Liturgy of St John Chrysostom, Coptic Liturgy of St Basil, Liturgy of St Cyril Archived 2012-05-09 at WebCite, Liturgy of St James Archived 15 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Understanding the Orthodox Liturgy, etc.

- ^ L. Gambero, Mary and the Fathers of the Church trans. T. Buffer (San Francisco: Ignatius, 1991), p. 35.

- ^ Guiley, Rosemary Ellen (2004). The Encyclopedia of Angels (Second ed.). p. 183. ISBN 0-8160-5023-6.

- ^ Medieval art: a topical dictionary by Leslie Ross 1996 ISBN 0-313-29329-5 p. 99

- ^ Christian iconography: a study of its origins by André Grabar 1968 Taylor & Francis p. 130

- ^ Annunciation Art, Phaidon Press, 2004, ISBN 0-7148-4447-0

- ^ The Annunciation to Mary by Eugene Laverdiere 2007 ISBN 1-56854-557-6 p. 29

- ^ The Oxford Companion to Christian Art and Architecture by Peter Murray 1996 ISBN 0-19-866165-7 p. 24

- ^ Medieval art: a topical dictionary by Leslie Ross 1996 ISBN 0-313-29329-5 p. 16

- ^ Paul Cavendish, "The Tridentine Mass"

- ^ Marion A. Habig, "Land of Mary Immaculate"

- ^ Emblems for Immaculate Conception "Birth of Mary: Meditation and Illustrations". All About Mary. International Marian Research Institute, University of Dayton. Archived from the original on 2008-12-11. Retrieved 2008-12-05.

- ^ The whole text Archived 2011-05-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ésotérisme, gnoses & imaginaire symbolique: mélanges offerts à Antoine Faivre by Richard Caron, Antoine Faivre 2001 ISBN 90-429-0955-2 p. 676

- ^ Divine Mirrors: The Virgin Mary in the Visual Arts by Melissa R. Katz and Robert A. Orsi 2001 ISBN 0-19-514557-7 p. 98

- ^ As the Virgin Mary remained an ever-virgin and sinless, it is viewed that the Virgin Mary could not thus suffer the consequences of Original Sin, which is chiefly Death. http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/3819.htm Nicea II Session 6 Decree

- ^ Nicaea II Definition, "without blemish"

- ^ Christopher Rengers, The 33 Doctors Of The Church, Tan Books & Publishers, 200, ISBN 0-89555-440-2

- ^ Mary H. Allies, St. John Damascene on Holy Images, Followed by Three Sermons on the Assumption London, 1899.

- ^ University of Dayton http://campus.udayton.edu/mary/resources/maryassump1.html

- ^ Dictionary of Mary, Catholic Book Publishing Co., New York, 1985

- ^ Ad Caeli Reginam 40

- ^ a b Guiley, Rosemary Ellen (2001). The Encyclopedia of Saints. Infobase Publishing. p. 162. ISBN 0-8160-4134-2.

- ^ Michael Freze, 1993, Voices, Visions, and Apparitions, OSV Publishing ISBN 0-87973-454-X

- ^ Secular ritual by Sally Falk Moore, Barbara G. Myerhoff 1977 ISBN 90-232-1457-9 p. 174

- ^ Emiliano Zapata by Samuel Brunk 1995 ISBN 0-8263-1620-4 p. 68

- ^ Moved by Mary by Anna-Karina Hermkens 2009 ISBN 0-7546-6789-8 p. 38

- ^ a b Encyclical Ad Caeli Reginam on the Vatican website

- ^ The encyclopedia of Protestantism edited by Hans Joachim Hillerbrand 2003 ISBN 0-415-92472-3 pp. 171–173

- ^ Mary in Western art by Timothy Verdon, Filippo Rossi 2005 ISBN 0-9712981-9-X p. 61

- ^ Christian art by Beth Williamson 2004 ISBN 0-19-280328-X pp. 102–106

- ^ a b c The Eastern Orthodox Church: Its Thought and Life by Ernst Benz 2009 ISBN 0-202-36298-1 pp. 4–9

- ^ Serbian orthodox fundamentals by Christos Mylonas 2003 ISBN 963-9241-61-X pp. 45–48

- ^ Encyclopedia of Catholicism by Frank K. Flinn, J. Gordon Melton 2007 ISBN pp. 244–245

- ^ a b c Ecclesiasticus II: Orthodox Icons, Saints, Feasts and Prayer by George Dion Dragas 2005 ISBN 0-9745618-0-0 pp. 177–178

- ^ America's Religions: From Their Origins to the Twenty-First Century by Peter W. Williams, 2008. ISBN 0-252-07551-X pp. 56–57

- ^ Keeping silence: Christian practices for entering stillness by C. W. McPherson ISBN 0-8192-1910-X, 2002 p. 48

- ^ The encyclopedia of world religions by Robert S. Ellwood, Gregory D. Alles 2007 ISBN 0-8160-6141-6 pp. 33–34

- ^ Mark Miravalle, 1993, Introduction to Mary, Queenship Publishing ISBN 978-1-882972-06-7 pp. 64–70

- ^ Butler's Lives of the Saints: August by Alban Butler, Paul Burns 1998 ISBN 0-86012-257-3 p. 147

References

[edit]- D'Ancona, Mirella Levi (1977). Garden of the Renaissance: Botanical Symbolism in Italian Painting. Firenze: Casa Editrice Leo S.Olschki. ISBN 9788822217899.

- D'Ancona, Mirella Levi (1957). The iconography of the Immaculate Conception in the Middle Ages and early Renaissance. College Art Association of America. ASIN B0007DEREA.

- Beckwith, John (1969). Early Medieval Art. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-20019-X.

- Arnold Hauser, Mannerism: The Crisis of the Renaissance and the Origins of Modern Art, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1965, ISBN 0-674-54815-9

- Levey, Michael (1961). From Giotto to Cézanne. Thames and Hudson,. ISBN 0-500-20024-6.

- Myers, Bernard (1965, 1985). Landmarks of Western Art. Hamlyn. ISBN 0-600-35840-2.

- Rice, David Talbot (1997). Art of the Byzantine Era. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-20004-1.

Further reading

[edit]- Dupre, Judith. Full of Grace: Encountering Mary in Faith, Art, and Life, 2010 ISBN 1-4000-6585-2

- Gustafson, Fred. The Black Madonna, 2008 ISBN 3-85630-720-6

External links

[edit]- Christian Iconography from Augusta State University – see under Virgin Mary, after alphabet of saints

- Birth of Mary in Art, All About Mary The University of Dayton's Marian Library/International Marian Research Institute (IMRI) is the world's largest repository of books, artwork and artifacts devoted to Mary, the mother of Christ, and a pontifical center of research and scholarship with a vast presence in cyberspace.

![Our Lady of Rokitno [pl], Poland, 1671](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/2f/Matka-Boza_Rokitno.jpg/136px-Matka-Boza_Rokitno.jpg)