War against Nabis

| Laconian War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

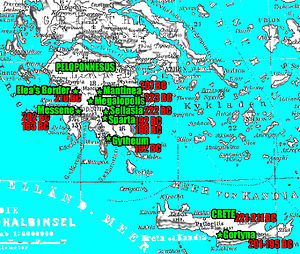

The Southern Peloponnesus | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 30,000+[1] |

| ||||||||

The Laconian War of 195 BC was fought between the Greek city-state of Sparta and a coalition composed of Rome, the Achaean League, Pergamum, Rhodes, and Macedon.

During the Second Macedonian War (200–196 BC), Macedon had given Sparta control over Argos, an important city on the Aegean coast of Peloponnese. Sparta's continued occupation of Argos at the end of war was used as a pretext for Rome and its allies to declare war. The anti-Spartan coalition laid siege to Argos, captured the Spartan naval base at Gythium, and soon invested and besieged Sparta itself. Eventually, negotiations led to peace on Rome's terms, under which Argos and the coastal towns of Laconia were separated from Sparta and the Spartans were compelled to pay a war indemnity to Rome over the next eight years. Argos joined the Achaean League, and the Laconian towns were placed under Achaean protection.

As a result of the war, Sparta lost its position as a major power in Greece. Subsequent Spartan attempts to recover the losses failed and Nabis, the last sovereign ruler, was eventually murdered. Soon after, Sparta was forcibly made a member of its former rival, the Achaean League, ending several centuries of fierce political independence.

Background

[edit]After the death of the Spartan regent Machanidas in 207 BC in battle against the Achaean League, Nabis overthrew the reigning king Pelops[Note 1] with the backing of a mercenary army and placed himself on the throne, claiming descent from the Eurypontid king Demaratus.[Note 2][5] By then, the traditional constitution of Lycurgus had already lost its meaning and Sparta was dominated by a group of its former mercenaries. Polybius described Nabis's force as "a crowd of murderers, burglars, cutpurses and highwaymen".[6] In 205 BC, Nabis signed a peace treaty with Rome, but in 201 BC he attacked the territory of Messene, at that time an ally of both parties, which Sparta had ruled until the mid 4th century BC. The Spartans captured Messene but were soon forced to abandon it when the army of Megalopolis[3] arrived under the command of Philopoemen. Later, they were decisively defeated at Tegea and Nabis was forced to check his expansionist ambitions for the time.[3][7]

During the Second Macedonian War, Nabis had another possibility for expansion. Philip of Macedon offered him the polis of Argos in exchange for Sparta defecting from the Roman coalition and joining the Macedonian alliance.[8] Nabis accepted and received control over Argos. When the war turned against Macedon, however, he rejoined the Roman coalition and sent 600 Cretan[Note 3] mercenaries to support the Roman army.[10][11] Philip was later decisively defeated by the Romans at the battle of Cynoscephalae,[12] but Sparta remained in control of Argos. After the war, the Roman army did not withdraw from Greece, but instead sent garrisons to various strategic locations across Greece to secure its interests.[13]

Nabis's reforms

[edit]In return for his assistance in the war, Rome accepted Nabis's possession of the polis of Argos. While Nabis was already King of Sparta, he made his wife Apia ruler of her hometown Argos. Afterwards, Apia and Nabis staged a financial coup by confiscating large amounts of property from the wealthy families of these cities, and torturing those who resisted them; much of the confiscated land was redistributed to liberated helots loyal to Nabis.[3][10] After increasing his territory and wealth by the aforementioned method, Nabis started to turn the port of Gythium into a major naval arsenal and fortified the city of Sparta.[5] His Cretan allies were already allowed to have naval bases on Spartan territory, and from these they ventured on acts of piracy.[Note 4] His naval buildup offered a chance even for the very poor to participate, as rowers, in the profitable employment. However, the extension of the naval capacities at Gythium greatly displeased the abutting states of the Aegean Sea and the Roman Republic.[3]

Nabis's rule was largely based on his social reforms and the rebuilding of Sparta's armed forces. The military of Lacedaemon, Sparta, had traditionally been based on levies of full citizens and perioeci (one of the free non-citizen groups of Lacedaemon) supported by lightly armed helots. From several thousands in the times of the Greco-Persian Wars, the numbers of full citizen Spartans had declined to a few hundred in the times of Cleomenes III. There were possibly several reasons for the decline of numbers, one of which was that every Spartan who was unable to pay his share in the syssitia (common meal for men in Doric societies) lost his full citizenship, although this did not exclude his offspring from partaking in the agoge (traditional Spartan education and training regime). As a result, the fielding of a respectable hoplite army without mercenaries or freed helots was difficult. Cleomenes increased the number of full citizens again and made the Spartan army operate with an increased reliance on more lightly armored phalangites of the Macedonian style.[15] However, many of these restored citizens were killed in the Battle of Sellasia and Nabis's politics drove the remainder of them into exile. In consequence, the heavy troops were no longer available in sufficient numbers. This led to a serious decline in Sparta's military power, and the aim of Nabis reforms was to reestablish a class of loyal subjects capable of serving as well-equipped phalangites (operating in a close and deep formation, with a longer spear than the hoplites'). Nabis's liberation of the enslaved helots was one of the most outstanding deeds in Spartan history. With this action, Nabis eliminated a central ideological pillar of the old Spartan social system and the chief reason for objection to Spartan expansion by the surrounding poleis (city-states). Guarding against helot revolt had been, until this time, the central concern of Spartan foreign policy, and the need to protect against internal revolt had limited adventurism abroad; Nabis's action abolished this concern with a single stroke. His freed helots received land from him and were wedded to wealthy wives of the exiled Spartan demos (all former full citizens) and widows of the rich elite, whose husbands had been killed at his orders.[5]

Preparations

[edit]| External images | |

|---|---|

The Achaean League was upset that one of its members had remained under Spartan occupation and persuaded the Romans to revisit their decision to leave Sparta's territorial gains intact. The Romans agreed with the Achaeans, as they did not want a strong and re-organized Sparta causing trouble after the Romans left Greece.[1]

In 195 BC, Titus Quinctius Flamininus, the Roman commander in Greece, called a council of the Greek states at Corinth to discuss whether or not to declare war on Nabis. Among the states whose delegates participated were the Aetolian League, Macedon, Rome, Pergamum, Rhodes, Thessaly and the Achaean League.[19] All the states represented favored war, except for the Aetolian League and Thessaly, both of which wanted the Romans to leave Greece immediately.[19][20] These two states offered to deal with Nabis themselves, but they met opposition from the Achaean League, which objected to any possible growth in the Aetolian League's power.[20] The modern historian Erich Gruen has suggested that the Romans may have used the war as an excuse to station a few legions in Greece in order to prevent the Spartans and the Aetolian League from joining the Seleucid King Antiochus III if he invaded Greece.[21]

Flamininus first sent an envoy to Sparta, demanding that Nabis either surrender Argos to the Achaean League or face war with Rome and her Greek allies.[22] Nabis refused to comply with Flamininus's ultimatum, so 40,000 Roman soldiers and their Greek allies advanced towards the Peloponnese.[22] Entering the Peloponnese, Flamininus joined his force with that of the Achaean commander, Aristaenos, who had 10,000 infantry and 1,000 cavalry in Cleonae. Together, they advanced towards Argos.[22]

Nabis had appointed his brother-in-law, the Argive Pythagoras, as commander of his garrison of 15,000 men in Argos.[23] As the Romans and the Achaean League were advancing towards the city, a young Argive named Damocles attempted to stir up a revolution against the Spartan garrison. With a few followers, he stood in the city's agora and shouted to his fellow Argives, exhorting them to rise in revolt. However, no mass uprising materialized and Damocles and most of his followers were surrounded and killed by the Spartan garrison.[23]

A few survivors from Damocles's group escaped from the city and went to Flamininus's camp. They suggested to Flamininus that, if he moved his camp closer to the city gates, the Argives would revolt against the Spartans.[23]

The Roman commander sent his light infantry and cavalry to find a position for the new camp.[23] Upon spotting the small group of Roman soldiers, a group of Spartan troops sallied forth from the gates and skirmished with the Romans about 300 paces from the city walls. The Romans forced the Spartans to retreat back into the city.[23]

Flamininus moved his camp to the position where the skirmish had occurred. For a day he waited for the Spartans to attack him but, when no attack came, he called a war council to discuss whether or not to press the siege. All the Greek leaders except Aristaenos thought that they should attack the city, as capturing it was their primary objective in going to war.[23] Aristaenos, on the other hand, argued that they should instead strike directly at Sparta and Laconia. Flamininus agreed with Aristaenos and the army marched to Tegea in Arcadia. The next day, Flamininus advanced to Caryae, where he waited for allied auxiliaries to reinforce him. These forces soon arrived and joined the Romans; they consisted of a contingent of Spartan exiles led by Agesipolis, the legitimate King of Sparta, who had been overthrown by the first Tyrant of Sparta, Lycurgus, twenty years earlier, and 1,500 Macedonians with 400 Thessalian cavalry sent by Philip.[1][23][24] News also reached the allies that several fleets had arrived off the Laconian shore: a Roman fleet under Lucius Quinctius with forty ships; a Rhodian fleet with eighteen ships, led by Sosilas, hoping that the defeat of Nabis would stop the pirates that plagued their ships; and a Pergamene fleet of forty ships under King Eumenes II of Pergamum, who hoped to gain more favor with Rome and Roman support if Antiochus invaded.[1][23][25]

Laconian campaign

[edit]Nabis drafted 10,000 citizens into his army and hired 3,000 additional mercenaries. Nabis's Cretan allies, who profited from the naval bases on his territory, dispatched 1,000 specially selected warriors to augment the 1,000 they had already sent to Sparta's aid.[26] Nabis, fearing that the Roman approach might encourage his subjects to revolt, decided to terrorize them by ordering the execution of eighty prominent citizens.[3] Flamininus left his base and descended upon Sellasia; while the Romans were making camp, Nabis's auxiliaries attacked them.[27] The sudden surprise attack briefly threw the allies into a state of confusion, but the Spartans retreated back to the city when the main body of legionary cohorts arrived.[27] As the Romans marched past Sparta on their way to Mount Menelaus, Nabis's mercenaries attacked the allies' rear. Appius Claudius, commander of the rearguard, rallied his troops and forced the mercenaries to retreat behind the city's walls, inflicting heavy casualties on them in the process.[27]

The coalition army then proceeded to Amyclae, from whence they plundered the surrounding countryside. Lucius Quinctius, meanwhile, received the voluntary surrender of several coastal towns in Laconia.[26][27] The allies then advanced on the largest city in the area, Sparta's port and naval arsenal at Gythium. As the land forces began to invest the city, the allied navy arrived. The sailors from the three fleets set to construct siege engines within a few days.[26] Though these machines had a devastating effect on the city walls, the garrison successfully held out.[26]

Eventually, Dexagoridas, one of the two garrison commanders, sent word to the Roman legate that he was willing to surrender the city.[26] This plan fell through when Gorgopas, the other commander, learned of it and slew Dexagoridas with his own hands.[26] Gorgopas continued to resist fiercely until Flamininus arrived with 4,000 additional troops that he had recently recruited.[26] The Romans renewed their assault and Gorgopas was forced to surrender, though he did secure the condition that he and his garrison could leave unharmed and return to Sparta.[26]

Siege of Sparta

[edit]During the siege at Gythium, Pythagoras had joined Nabis at Sparta, bringing with him 3,000 men from Argos.[26] When Nabis discovered that Gythium had surrendered he decided to send an envoy to Flamininus to open negotiations on the terms of a peace.[25] Nabis offered to withdraw the rest of his garrison from Argos and to hand over to the Romans any deserters and prisoners.[28] Flamininus called another war council. Most of the council felt that they should capture Sparta and unseat Nabis.[29]

Flamininus replied to Nabis by proposing his own terms, under which Sparta and Rome would conclude a six-month truce if Nabis would surrender Argos with all his garrisons from the Argolid; give the coastal Laconian cities autonomy and give them his fleet; pay a war indemnity over the next eight years and not enter into alliances with any Cretan cities.[24][30] Nabis rejected this offer, claiming that he had enough supplies to withstand a siege.[31] Flamininus therefore led his force of 50,000 men to Sparta and, after defeating the Spartans in a battle outside the city, began investing the city.[32] Flamininus resolved not to lay a regular siege to the city but to instead try and storm it.[2] The Spartans initially held out against the allies, but their resistance was hampered by the fact that the Romans' large shields made missile attacks futile.[29]

The Romans launched an assault on Sparta and took the walls, but their advance was initially impeded by the narrowness of the roads in the city's outskirts. However, the streets grew wider as they advanced into the city's center, and the Spartans were forced further and further back.[29] Nabis, seeing his defenses collapsing, tried to flee, but Pythagoras rallied the soldiers and ordered them to set fire to the buildings closest to the walls.[29] Burning debris was thrown on the coalition's soldiers entering the city, causing many casualties. Observing this, Flamininus ordered his forces to withdraw to their base.[29] When the attack was renewed later, the Spartans managed to hold off the Roman assaults for three days before Nabis, seeing that the situation was hopeless, decided to send Pythagoras with an offer of surrender.[33] At first, Flaminius refused to see him, but when Pythagoras came to the Roman camp a second time Flamininus accepted the surrender, with the conditions of the treaty being the same as Flamininus had previously proposed.[33] The treaty was later ratified by the Senate.[3]

The Argives revolted when they heard that Sparta was under siege. Under the Argive Archippas, they attacked the garrison commanded by Timocrates of Pellene.[33] Timocrates surrendered the citadel on condition that he and his men could leave unharmed.[33] In return all the Argives serving in Nabis's army were allowed to return home.[33]

Aftermath

[edit]

After the war Flamininus visited the Nemean Games in Argos and proclaimed the polis free.[2][34] The Argives immediately decided to rejoin the Achaean League. Flamininus also separated all coastal cities of Laconia from Spartan rule and placed them under Achean protection.[2] The remains of Sparta's fleet were put under custody of these coastal cities.[2] Nabis also had to withdraw his garrisons from Cretan cities and revoke several social and economic reforms that had strengthened Sparta's military capabilities.[30][35] The Romans did not, however, remove Nabis from the Spartan throne. Even though Sparta was a landlocked and effectively powerless state, the Romans wanted an independent Sparta to act as a counterweight against the growing Achaean League. Nabis's allegiance was secured by the fact that he had to surrender five hostages, amongst them his son, Armenas.[30] The Romans did not restore the exiles, wishing to avoid internal strife in Sparta. They did, however, allow any woman who was married to an ex-helot but whose husband was in exile to join him.[2][30][35]

After the legions under Flamininus had returned to Italy, the Greek states were once again on their own. The dominant powers in the region at this time were the kingdom of Macedon, which had recently lost a war against Rome, the Aetolians, the strengthened Achaean League and a reduced Sparta. The Aetolians, who had opposed the Roman intervention in Greek affairs, incited Nabis to retake his former territories and position among the Greek powers.[3] By 192, Nabis who had built a new fleet and strengthened his army, besieged Gythium. The Achaeans responded by sending an envoy to Rome with a request for help.[3] In response the Senate sent the praetor Atilius with a navy to defeat Nabis's navy as well as an embassy headed by Flamininus.[3] Instead of waiting for the Roman fleet to arrive, the Achaean army and navy headed towards Gythium under the command of Philopoemen. The Achaean fleet was defeated by the recently constructed Spartan fleet, with the Achean flagship falling to pieces in the first ramming attack.[3] On land as well the Achaeans could not defeat the Spartan forces outside Gythium and Philopoemen retreated to Tegea.[3] When Philopoemen reentered Laconia for a second attempt his forces were ambushed by Nabis's but nevertheless he managed to gain a victory.[3] The Achaeans now could ravage Laconia for thirty days unopposed while the Spartan troops remained in their fortified city. Plans for capturing Sparta itself had been laid by the time the Roman envoy Flamininus arrived and convinced the Achaean strategus Philopoemen to spare it.[3] For the time being Nabis decided to accept the status quo in return and surrender under the same conditions as the last treaty.[3][35]

Since Sparta's army was now weakened, Nabis appealed to the Aetolians for help.[3] They sent to Sparta 1,000 cavalry under the command of Alexamenus. The story goes that while Nabis was observing his army's drills, the Aetolian commander Alexamenus charged at him and killed him with his lance.[36] Afterwards the Aetolian troops seized the palace and set about looting the city but its Sparta were able to rally and drive them from Sparta.[36] As Sparta was in turmoil Philopoemen entered the city with the Achaean army and made Sparta a member state of the League. The polis of Sparta was allowed to keep its laws and territory, but the exiles, and their rule of the Spartan warrior demos were not restored.[37]

In 189 BC, the hostages taken by Rome, excluding Nabis's son, who fell ill and died, were allowed to return to Sparta.[38][39] Still deprived of any port and suffering from political and economic problems from having the hostile exiles close by and not having access to the sea, the Spartans captured the city of Las, which was the home of many exiles and a member of the Union of free Laconians.[38][40] The Acheans officially adopted this as the reason to finish Spartan independence once and for all. They demanded the surrender of the people responsible for the attack.[38] The culprits responded by murdering thirty pro-Achaean citizens, seceding from the League and requesting Roman tutelage.[38] The Romans, who wanted to see division in the League, did nothing about the situation.[38] In 188, Philopoemen entered northern Laconia with an army and the Spartan exiles who insisted on returning to Sparta. He first massacred eighty anti-Achaeans at Compasium, and then had the wall that Nabis built around Sparta demolished. Philopoemen then restored the exiles and abolished Spartan law, introducing Achaean law in its place.[38] Thus ended Sparta's role as a major power in Greece, while Achaea became dominant throughout the Peloponnese.[41]

Notes

[edit]

- ^ Traditionally, Sparta had been ruled by two kings, one of the Eurypontid dynasty and one of the Agiad dynasty. However, decades before Nabis took power in a military coup, the traditional Spartan constitution had already crumbled. In 227 BC, the Agiad king Cleomenes III killed four of the five ephors (elected guards of the constitution) and deposed, perhaps murdered, the Eurypontid king Archidamus V. His new co-ruler became his brother Eucleidas, also a member of the Agiad dynasty, but on the Eurypontid throne. They undertook social reforms and received subsidies from Ptolemaic Egypt with the ambition of reforming and strengthening the Spartan military in Macedonian fashion. This possible threat to the Macedonian hegemony in Greece was crushed by the Antigonids in the Battle of Sellasia and the Ptolemys ceased their financial support. From the consequent banishment of Cleomenes III, in 222 BC, until 219 BC, Sparta was a republic without kings. In 219 BC, the Agiad Agesipolis III and the Eurypontid Lycurgus were made kings.[3] Lycurgus deposed Agesipolis in 215 BC,[3] although the latter spent years trying to retake his throne and led a force of Spartan exiles in the Roman-Spartan War.[3] Lycurgus reigned by himself until his death in 210 BC. His successors were his son Pelops, as Eurypontid king, and the tyrant Machanidas, who claimed no royal origin. They reigned together until 207 BC, when Machanidas was slain by Philopoemen in the Battle of Mantinea. After Machanidas's death, Nabis seized the throne in a coup and had Pelops murdered.

- ^ The correct title for Nabis's office is ambiguous. He himself claimed descent from the Eurypontid Spartan king Demaratus and is presented with the title basileus on coins.[4] On the other hand historians such as Livy and Polybius referred to him with the title of tyrant because he had overthrown the old government of Sparta. The home countries of both authors, Rome and the Achean League, were involved in this conflict and considered a possible restoration of one of the toppled governments during this war.

- ^ Cretan in this context can mean someone from the island of Crete, but it also meant a fighting style of archers that could alternately fight with sword and shield. This style was introduced by the inhabitants of Crete, but the troops referred to as Cretans or Cretan archers were by no means all Cretan, particularly in mercenary forces.[9]

- ^ Piracy included not only seaborne ventures against trade ships, but also amphibious operations against coastal settlements with the aim of capturing inhabitants and selling them as slaves. Plautus, a Roman playwright of this time, described the result of such a raid in his play Poenulus.[14]

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d Holleaux, Rome and the Mediterranean; 218–133 B.C., 190

- ^ a b c d e f Holleaux, Rome and the Mediterranean; 218–133 B.C., 191

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Smith [1]

- ^ Ernst Baltrusch, Sparta, 113

- ^ a b c Green, Alexander to Actium: The Historical Evolution of the Hellenistic Age, 302

- ^ Polybius 13.6

- ^ Polybius 16.13

- ^ Livy 32.39

- ^ Appian. "§32". History of Rome: The Syrian Wars. Retrieved 2007-01-14.

- ^ a b Cartledge and Spawforth, Hellenistic and Roman Sparta: A tale of two Cities, 74

- ^ Livy 32.40

- ^ Livy 33.10

- ^ Livy 33.31

- ^ Plautus. "Poenulus". Retrieved 2007-01-12.

- ^ Warfare in the Classical World, p. 73 (Macedonian infantry) on the equipment of the Macedonian phalangites

- ^ Warfare in the Classical World, pp. 34f (Greek Hoplite (c. 480BC)) p. 67 (Iphicrates reforms)

- ^ "Battle of Marathon". Ancient Mesopotamia. Archived from the original on February 24, 2006. Retrieved 2006-12-26.

- ^ "Roman Conquest". The Romans. Archived from the original on 2007-10-30. Retrieved 2006-12-26.

- ^ a b Cartledge and Spawforth, Hellenistic and Roman Sparta:A tale of two Cities, 75

- ^ a b Livy 34.24

- ^ Gruen, The Hellenistic World and the Coming of Rome, 450

- ^ a b c Livy 34.25

- ^ a b c d e f g h Livy 34.26

- ^ a b Green, Alexander to Actium: The Historical Evolution of the Hellenistic Age, 415

- ^ a b Livy 34.30

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Livy 34.29

- ^ a b c d Livy 34.28

- ^ Livy 34.33

- ^ a b c d e Livy 34.39

- ^ a b c d Livy 34.35

- ^ Livy 34.37

- ^ Livy 34.38

- ^ a b c d e Livy 34.40

- ^ Livy 34.41

- ^ a b c Cartledge and Spawforth, Hellenistic and Roman Sparta:A tale of two Cities, 76

- ^ a b Livy 35.35

- ^ Cartledge and Spawforth, Hellenistic and Roman Sparta:A tale of two Cities, 77

- ^ a b c d e f Cartledge and Spawforth, Hellenistic and Roman Sparta:A tale of two Cities, 78

- ^ Polybius 21.2

- ^ Green, Alexander to Actium: The Historical Evolution of the Hellenistic Age, 423

- ^ Cartledge and Spawforth, Hellenistic and Roman Sparta:A tale of two Cities, 79

- ^ "Ancient coins of Peloponnesus". Digital Historia Numorum. Retrieved 2006-01-12.

References

[edit]Primary sources

[edit]- Livy, translated by Henry Bettison, (1976). Rome and the Mediterranean. London: Penguin Classics. ISBN 0-14-044318-5.

- Polybius, translated by Ian Scott-Kilvert and introduced by Frank W. Walbank (1979). The Rise of the Roman Empire. New York: Penguin Classics. ISBN 0-14-044362-2.

Secondary sources

[edit]- Ernst Baltrusch, (1998). Sparta. Munich: C.H. Beck. ISBN 3-406-41883-X

- Paul Cartledge and Antony Spawforth, (2002). Hellenistic and Roman Sparta: A tale of two cities. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-26277-1

- Peter Green, (1990). Alexander to Actium: The Historical Evolution of the Hellenistic Age, (2nd edition). Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 0-500-01485-X.

- Erich Gruen, (1984). The Hellenistic World and the Coming of Rome. Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-05737-6

- Maurice Holleaux, (1930). Cambridge Ancient History: Rome and the Mediterranean; 218–133 B.C., (1st edition) Vol VIII. Los Angeles: Cambridge University Press.

- William Smith, (1873). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. London: John Murray.

- John Warry (1995; edition 2006). Warfare in the Classical World London (UK), University of Oklahoma Press, Norman Publishing Division of the University by special arrangement with Salamander Books Ltd. ISBN 0-8061-2794-5