Robert L. M. Underhill

Robert Lindley Murray Underhill | |

|---|---|

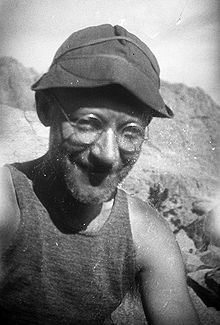

Robert L. M. Underhill in the Sierra Nevada in 1931. | |

| Born | March 3, 1889, |

| Died | May 11, 1983 (aged 94) |

| Known for | Mountaineering |

Robert Lindley Murray Underhill (March 3, 1889 – May 11, 1983) was an American mountaineer best known for introducing modern Alpine style rope and belaying techniques to the U.S. climbing community in the late 1920s and early 1930s.

Family and early life

[edit]His father, Abram Sutton Underhill (1852–1942) was an attorney, banker and prominent Quaker. His sister Ruth Murray Underhill (1883–1984) earned her PhD from Columbia University and was a social worker, anthropologist and author. Underhill's full name combined his maternal grandfather's name plus his father's surname.[1] He received an A.B. degree from Haverford College in 1909. At that time, Haverford was an elite Quaker college for men. He received a PhD from Harvard in 1916. He was an instructor in mathematics at Harvard in 1918, and a tutor and then instructor in philosophy at Harvard from 1925 to 1931. During that period, he was an active member of the Harvard Mountaineering Club. He began climbing in the Alps about 1910. His academic life's work was a study of logic.[2]

Mountaineering accomplishments

[edit]He was a longtime member of the Appalachian Mountain Club and editor of its journal Appalachia from 1928 to 1934.[3]

On August 4, 1928, Underhill, accompanied by Miriam O'Brien and guides Armand Charlet and G. Cachat, completed the first ascent of the traverse from the Aiguilles du Diable to Mont Blanc du Tacul in the Alps.[4] This route involves "climbing five outstanding summits over 4000 meters in superb surroundings."[5] On this same trip, Underhill completed guided ascents of the Peuterey and Brenva ridges of Mont Blanc. His climbing partner Miriam O'Brien was later to become his wife, and a famous mountaineer in her own right.

Underhill and Kenneth Henderson were responsible for introducing technical mountaineering to Grand Teton National Park in 1929, the year the park was formed. They completed the first ascent of the east ridge of the Grand Teton.

In 1930, he returned to the Tetons, and was unsuccessful in a solo attempt on the North Ridge of the Grand Teton.

His article On the Use and Management of the Rope in Rock Work was published in the Sierra Club Bulletin in February, 1931. This influential 22 page article covered rope use, knots, belaying, "roping down" (now called rappelling or abseiling), and the use of slings. Writing during a period when many climbers still resisted such safety innovations, Underhill described roped team climbing as "one of the finest experiences that mountaineering can afford."[6]

He was back in the Grand Tetons for six weeks the summer of 1931, completing on July 15 a first ascent of the southeast ridge of the Grand Teton, a route which now bears his name. On July 19, 1931, Underhill and park ranger Fritiof Fryxell completed the "remarkable" first ascent of the North Ridge of the Grand Teton, which is rated IV, 5.7 in the Yosemite Decimal System.[7]

Departing Wyoming, Underhill went on to California at the invitation of Sierra Club leader Francis P. Farquhar, for the purpose of teaching the most advanced techniques of roped climbing and belaying developed in the Alps. Underhill began by instructing a group of Sierra Club members in those techniques in the Minarets, practicing on the slopes of Mount Ritter and Banner Peak.[8] After this introductory course, an advanced group led by Underhill and including Norman Clyde, Jules Eichorn, Lewis Clark, Bestor Robinson and Glen Dawson traveled south to the Palisades, the most rugged and alpine part of the Sierra Nevada.[9] There, on August 13, 1931, this party completed the first ascent of the last unclimbed 14,000+ foot peak in California, which remained unnamed due to its remote location above the Palisade Glacier. After a challenging ascent to the summit, the climbers were caught in an intense lightning storm, and Eichorn barely escaped electrocution when "a thunderbolt whizzed right by my ear". The mountain was named Thunderbolt Peak to commemorate that close call.

Three days later on August 16, Underhill, Clyde, Eichorn and Dawson completed the first ascent of the East Face of Mount Whitney, the highest peak in the contiguous United States.[10] By California standards at that time, the route was considered extremely exposed, especially the famous Fresh Air Traverse.[11] Steve Roper called this route "one of the classic routes of the Sierra, partly because of its spectacular location and partly because it was the first really big wall to be climbed in the range."[12] Porcella & Burns wrote that "the climb heralded a new standard of technical competence in Californian rock climbing."[13] Underhill himself commented that "the beauty of the climb lies chiefly in its unexpected possibility, up the apparent precipice, and in the intimate contact it affords with the features that lend Mount Whitney its real impressiveness."[14]

Bestor Robinson described Underhill's influence on California rock climbing in a 1934 Sierra Club Bulletin article: "The seed of the lore of pitons, carabiners, rope-downs, belays, rope traverses, and two man stands was sown in California in 1931 by Robert L. M. Underhill, a member of the Appalachian Mountain Club, with considerable experience in the Alps. That seed has sprouted and grown in California climate with exuberant vigor sufficient to satisfy the most vociferous Chamber of Commerce."[15]

He married mountaineer Miriam O'Brien on January 28, 1932, and they had two sons, Robert and Brian, born in 1936 and 1939. After World War II, he climbed with his wife in the Wind River Range of Wyoming, the Mission, Swan and Beartooth ranges of Montana, and the Sawtooth range of Idaho.

Antisemitic views

[edit]In 1939 and 1946, Underhill wrote letters to friends at the Sierra Club and the American Alpine Club in which he referred to Jewish climbers as "kikes", "mutts" and "lowgrade".[16] The letter were documented in two books written by historian Maurice Isserman, published in 2010 and 2016.[16] The antisemitic attacks in the letters were directed in particular at Jewish mountaineering writer James Ramsey Ullman.[16] Underhill also expressed his opinion that Jewish people "lacked the character and physical traits to be successful in challenging mountain environments."[16]

In April 2022, the AAC's interim CEO, Jamie Logan, received an email from club member Brad Rassler that asked if the club was aware of the letters.[17] The AAC had previously given the Robert and Miriam Underhill Award annually for 39 years "to a person who, in the opinion of the selection committee, has demonstrated the highest level of skill in the mountaineering arts and who, through the application of this skill, courage, and perseverance, has achieved outstanding success in the various fields of mountaineering endeavor." As a result of the discovery of the letters, club leadership decided to remove Underhill's name from the award. Three previous recipients of the award, Lynn Hill, Peter Croft and Alex Honnold, expressed dismay at Underhill's slurs and support for the renaming.[16] In January 2023, the club announced that the award would be now be called the Pinnacle Award.[17]

Legacy

[edit]The Underhill Couloir above the Palisade Glacier is a key part of his 1931 first ascent route on Thunderbolt Peak, and is named in his honor.

Bob's Towers (13,040 feet/3,970 meters) in the Wind River Range of Wyoming is named after Underhill, who made the first ascent with his wife in 1939.[18][19]

References

[edit]- ^ http://www.ferristree.com/updtaes/john2.htm%7C Bombs & Bones: A Ferris Family Tree (retrieved September 17, 2009)

- ^ "In Memoriam", Henderson, Kenneth A., American Alpine Journal, 1984, pages 344 - 347 (retrieved September 17, 2009)

- ^ Roper, Steve; Steck, Allen (1979). Fifty Classic Climbs of North America. San Francisco: Sierra Club Books. ISBN 0-87156-292-8. page 149

- ^ Milner, C. Douglas, Mont Blanc & the Aguilles, page 92 (Robert Hale Limited, London, 1955)

- ^ Rébuffat, Gaston, The Mont Blanc Massif: The 100 Finest Routes, Translated from the French by Jane and Colin Taylor, page 140 (Kaye & Ward, London and Oxford University Press, New York, 1974) ISBN 0-19-519789-5

- ^ Underhil, Robert L. M. (February 1931). "On the Use and Management of the Rope in Rock Work" (PDF). Sierra Club Bulletin. 16 (1). San Francisco: Sierra Club: 67–88. Retrieved 2009-12-15.

- ^ Roper, Steve; Steck, Allen (1979). Fifty Classic Climbs of North America. San Francisco: Sierra Club Books. ISBN 0-87156-292-8. pages 147 - 152

- ^ Farquhar, Francis P., History of the Sierra Nevada (University of California Press, Berkeley, 1965) ISBN 0-520-01551-7

- ^ Croft, Peter; Wynne Benti (2008). "Chapter 5". Climbing Mt. Whitney: The Complete Hiking & Climbing Guide (3rd ed.). Bishop, CA: Spotted Dog Press. pp. 24–25. ISBN 978-1-893343-14-6.

- ^ Roper, Steve; Steck, Allen (1979). Fifty Classic Climbs of North America. San Francisco: Sierra Club Books. pp. 276–282. ISBN 0-87156-292-8.

- ^ Croft, Peter; Wynne Benti (2008). "Chapter 1". Climbing Mt. Whitney: The Complete Hiking & Climbing Guide (3rd ed.). Bishop, CA: Spotted Dog Press. pp. 99–104. ISBN 978-1-893343-14-6.

- ^ Roper, Steve, The Climber's Guide to the High Sierra (San Francisco, Sierra Club Books, 1976) ISBN 0-87156-147-6

- ^ Stephen Porcella; Cameron M. Burns (1998). Climbing California's Fourteeners: The Route Guide to the Fifteen Highest Peaks. The Mountaineers Books. ISBN 978-0-89886-555-4.

- ^ Roper, Steve; Steck, Allen (1979). Fifty Classic Climbs of North America. San Francisco: Sierra Club Books. ISBN 0-87156-292-8. page 279

- ^ Robinson, Bestor (February 1974). "The First Ascent of the Higher Cathedral Spire". In Galen Rowell (ed.). The Vertical World of Yosemite. 1973 (republished 1995). Berkeley, CA: Wilderness Press. pp. 8–14. ISBN 0-911824-87-1.

- ^ a b c d e Rassler, Brad (May 5, 2022). "Antisemitic Statements by a Climbing Pioneer Prompt the American Alpine Club to Rename a Prestigious Honor". Outside. Retrieved May 10, 2022.

The Robert and Miriam Underhill Award, given since 1983 to legends like Lynn Hill, Yvon Chouinard, Conrad Anker, and Alex Honnold, will be rebranded because of racist remarks made in the 1930s and 1940s by Robert L.H. Underhill, a major figure in the history of U.S. mountaineering

- ^ a b Dreier, Frederick (13 January 2023). "American Alpine Club Award Parts Ways with Its Antisemitic Namesake". Climbing. Retrieved 17 January 2023.

- ^ "Bobs Towers, Wyoming". Peakbagger.com. retrieved October 3, 2009

- ^ "Miriam Peak". SummitPost.org. retrieved October 3, 2009