Robert Bell (speaker)

Robert Bell | |

|---|---|

| Speaker of the House of Commons | |

| In office 1572–1576 | |

| Preceded by | Sir Christopher Wray |

| Succeeded by | Sir John Popham |

| Serjeant-at-Law | |

| In office 22 January 1577 – 25 July 1577 | |

| Preceded by | Sir Edward Saunders |

| Succeeded by | Sir John Jeffrey |

| Lord Chief Baron of the Exchequer | |

| In office 24 January 1577 – 27 July 1577 | |

Sir Robert Bell SL (died 1577) of Beaupré Hall, Norfolk, was a Speaker of the House of Commons (1572–1576), who served during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I.

He was legal counsel (1560) and recorder (1561) for King's Lynn, legal counsel for Great Yarmouth (1562–1563),[1] and justice of the peace of the quorum for Norfolk (1564). He became a bencher in the Middle Temple in 1565 and was elected Autumn Reader that same year and Lent Reader in 1571.[2]

In 1576 Bell was appointed Commissioner of Grain, Musters by 1576 and in 1577 he was knighted and appointed Serjeant-at-Law and Chief Baron of the Exchequer.[2]

Early involvement in the law and politics

[edit]Bell gained admittance to the Middle Temple where he was called to the bar.[2] He was elected to sit as a bencher and subsequently elected Lent and Autumn Reader. During the period when he attended the Middle Temple, the religious denomination of the pupils and Masters of the bench was primarily Catholic, with emerging factions of Protestants, balancing the Elizabethan membership.[3] He achieved success at the beginning of his legal career, on (6 March 1559), accomplishing favorable results for the patentees of the lands of John White, bishop of Winchester, involved in a suit that protected their interest for which he was of counsel with Alexander Nowell.[4]

Bell's further career was launched by his fortunate marriage (15 October 1559), to Dorothie Beaupre. It gained him not only a family, but a large estate in Outwell, along with local offices and status that came with it; including that of MP, for King's Lynn.[2]

During the 1563, 1566, and 1571 parliaments, Bell made a nuisance of himself to the government, and was considered a radical. He was noted by William Cecil as one of the two leading trouble makers during the 1566 session.[2][5] Elizabeth I noted his maverick style of behavior, a "on 19 October 1566, "[Bell] did argue very boldly" to pursue the succession question; "in the face of the Queen's command to leave it alone".[2] That year, Bell was lampooned by Thomas Norton as "Bell the Orator" together with others who served on the succession committee.[2] HoP

Parliament of 1571

[edit]

During the next parliament (5 April 1571) Bell launched an attack on the Queen's purveyors. He said that they took "under pretence of her Majesty's service what they would at what price they themselves liked..." In 1576, this precedent was recalled by Peter Wentworth during his motion for liberty of speech.[2]

On 19 April 1571, Bell was an advocate for the residents of less fortunate boroughs, " 'and in a loving discourse showed that it was necessary that all places should be provided for equally'." "but because some boroughs had not 'wealth to provide fit men' outsiders could sometimes be returned and no harm done". He further, proposed that all boroughs who sought to nominate a nobleman, should suffer a substantial financial penalty [£40], "mindful, no doubt of the power of the Duke of Norfolk in his county."[2]

From 1570 to 1572, Bell served as crown counsel,[5] and, perhaps, it was Bell's outspokenness, hitherto, that revealed his niche, as shortly following these events, he was recommended by William Cecil for Speaker (Prolocutor),[6] elected by the House, and approved by Elizabeth I, 8 May 1572.[7] 'The Queen on her part', he was told, had 'sufficiently heard of your truth and fidelity towards her and... understandith your ability to accomplish the same.'[2]

Bell's second disabling speech of that day was full of luminous detail and "was a model of circumspection:, a lawyer's piece larded with legal precedent; in his careful transmission of royal messages and his preference that attempts to persuade a reluctant queen should be by written arguments rather than by his spoken word;"[5][2]

Speaker

[edit]William Cecil, recommended Bell for Speaker in 1572.[6]

While Speaker, Bell presided over some of the more dynamic issues of the Elizabethan Parliaments, notably, the security of the realm, and a session concerning the question of Mary, Queen of Scots; where he was advised to shorten the discussion upon receiving a royal message that was whispered in his ear by Christopher Hatton.[8]

In 1575, he revisited the succession question, and on this occasion respectfully, petitioned Elizabeth "to make the kingdom further happy in her marriage, so that her people might hope for a continual succession of benefits in her posterity." Although he exhibited great courtesy during the course of his plea, Elizabeth still refused.[7]

Bell helped forge the realm under Elizabeth's rule, and following the 1576 session he was honorably rewarded and nominated for membership of a high powered committee for a special visitation of Oxford, that included Christopher Wray, Edwin Sandys then bishop of London and John Piers then bishop of Rochester and four others. (State Papers, Domestic, Elizabeth, p. 543)

Knighthood and reputation

[edit]In 1577, during the New Year's promotions, Elizabeth I, conferred a knighthood on Bell, made him her Serjeant-at-Law, and appointed him Chief Baron of the Exchequer; a post that he retained during the period that Francis Drake wrote the government, claiming his bounty to build his three ships in Aldeburgh, together with the arrangements he secured from his investors, for his 1577, voyage to circumnavigate the globe.[9]

James Dyer, Edmund Plowden and the historian, William Camden who considered him a 'lawyer of great renowne,' a "Sage and grave man, famous for his knowledge in the law, and deserving the character of an upright judge," admired Bell.[11][1][5]

Death and legacy

[edit]While presiding as judge at the Oxford assizes, at the session later called the Black Assize, Bell became exposed to prisoners of foul condition during the trial of a bookseller who had slandered the Queen. Bell, with an estimated 300 others, caught gaol fever.[5] (Camden, Annals, bk. 2.376) He then moved on to Leominster, and after presiding over the assize in that district, fell ill. On 25 July, he drafted a codicil to his will, in which he made his "Loving wife Dorothie" sole executor.[12]

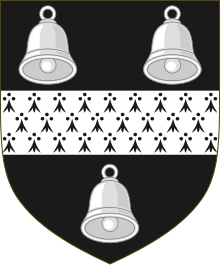

Before his illness, Bell had commissioned heraldic stained glass panels, representing marital alliances of the Beaupre and the Bell families. The panels were originally near the entry to Beaupré Hall, Norfolk. They were later cut down in size and relocated to the rear of the Hall; perhaps after 1730 when the antiquarian Beaupré Bell succeeded to the property.[7]

After his death in 1741, William Greaves, husband of Beaupré Bell's sister Dorothy Beaupré Bell, succeeded to the Hall. She was executrix to her brother, and preserved the stained glass. Greaves changed his surname to Beaupré-Bell. Their daughter Jane brought it by marriage to Richard Townley (1689–1762) into the Townley family, who held Beaupré Hall until it passed into the hands of Edward Fordham Newling, and his brother.[13][14][15] He anticipated the Hall's ruin, and wished that the stained glass panels would be placed in the care and possession of the Victoria & Albert Museum, London, where they are currently on display.

After Bell's death in 1577, John Peyton married Bell's widow Dorothy. From her estate, Peyton gained position and status in the county of Norfolk, and later became lieutenant of the Tower of London.

Family

[edit]Robert Bell married three times. His wives were:[5]

- Mary Chester, daughter of Anthony Chester.

- Elizabeth Anderson (d. 1556–1558?), widowed daughter in law of Edmund Anderson, Chief Justice of the Common Pleas.

- Dorothie Beaupré, daughter and co-heiress of Edmonde Beaupré (d.1567) of Beaupré Hall, Norfolk, by his wife Katherine Wynter, widow of John Wynter (Captain of the Castle of Mayett, France), daughter of Phillip Bedingfeld of Ditchingham, Norfolk.

These marriages brought significant connections. "Amongst the many great families with whom the Bells were connected by their various marriages, we may mention.... Beaupre, [Montfort], De Vere, Bedingfeld, Knyvett, Osbourne, Wiseman, Deering, Chester, Oxburgh, le Strange, Dorewood, Oldfield, Peyton, and Hobart, all persons of great eminence and distinction."[7][16]

1. His first son, Sir Edmond Bell (de Beaupre)[17] bap. 7 April 1562, bur. 22 Dec 1607, MP for King's Lynn, & Aldeburgh 'invested heavily in privateering,'[18][19] married 1., Anne the daughter of Peter Osbourne and Anne Hays 2. Elizabeth Inkpen 3. Muriell Knyvet the daughter of Thomas Knyvet, 1st Baron Knyvet High Sheriff of Norfolk (c. 1539–1618) and Merriell Parry, the daughter of Thomas Parry (Comptroller of the Household) and Anne Reade.

2. His second son Sir Robert Bell (de Beaupre)[17] b. (c. 1563, d. 1639), was a 'Captain of a company in the low countries' MP, built gun ships for the Navy.

3. His third son, Sinolphus Bell, Esq., b. March 1564, d. 1628, of Thorpe Manor, issue 8 sons, 3 dau., of Norfolk, married Jane (Anne) daughter of Christopher Calthrop and Jane Rookwood (daughter of Roger Rookwood) is listed among the knights of a committee to drain the fens.

4. His fourth son, Beaupre Bell b. c. 1570, d. 1638, literary scholar of Cambridge, admitted to Lincoln's Inn, 1594, was made Governor of the Tower of London in 1599.[20]

5. His fifth son, Phillip Bell b. 14 June 1574, d. after 1650, Fellow of Queens College, Cambridge (1593–7) [5], Captain and Governor of Bermuda (1627), Barbados, and Founding Governor of Providence Island, married 1. Anne Peyton 2. Mary, daughter of Daniel Elfrith.

6. His daughter, Mary Bell b. before 1561, d. 14 September 1585,[21] married on 6 August 1582 Sir Nicholas le Strange of Norfolk;[22] the son of Hamon le Strange (c.1530–1580) and Elizabeth Hastings; daughter of Sir Hugh Hastings of Elsing, de jure 14th Lord Hastings (d. 1540).

7. His daughter, Dorothy b. 19 October 1572, d. 30 April 1640, married Henry Hobart,[23] Chief Justice of the Common Pleas; who laboured together with Francis Bacon, to draft and procure the charters for the London and Plymouth Company.[24]

8. His daughter, Frances b. (posthumous) 2 December 1577, d. 9 November 1657, married Sir Anthony Dering of Kent (1558–1636), JP, of Surrenden Dering in Pluckley, Kent; the parents of Sir Edward Dering, 1st baronet (1598–1644), who married Elizabeth (1602–1622), daughter of Sir Nicholas Tufton, 1st earl of Thanet.[25]

Sources

[edit]- ^ a b Foss, E., Lives of the Judges, Vol. V, London 1857, pp. 458–61

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Bell, Robert (d.1577), of the Middle Temple, London and Beaupré Hall, Outwell, Norf. History of Parliament Online". www.historyofparliamentonline.org.

- ^ Williamson, J. B., The History of the Temple of London, London, John Murray (2nd ed. 1925)

- ^ House of Commons, Journal Volume 1, 6 March 1559, pb. 1802, Sponsor BHOL: History of Parliament Trust

- ^ a b c d e f Graves, M. A.R., 'Bell, Sir Robert (d. 1577)',ODNB, OUP, 2004 accessed 13 Feb 2005

- ^ a b MacCaffrey, W. T., 'Cecil William, first Baron Burghley (1520/21–1598),’ODNB, OUP, 2004 accessed 15 April 2005

- ^ a b c d Manning, J. A., Speakers, pb. Myers and Company, London pp. 242, 245

- ^ MacCaffrey, W. T., 'Hatton, Sir Christopher (c.1540–1591)’, ODNB, OUP, 2004 accessed 7 May 2005

- ^ Bawlf, S., The Secret Voyage of Sir Francis Drake 1577–1580, pb. Walker Publishing Co. 2003, p. 67

- ^ Metcalfe, Walter Charles (1885). A Book of Knights Banneret, Knights of the Bath, and Knights Bachelor: Made Between the Fourth Year of King Henry VI and the Restoration of King Charles II and Knights Made in Ireland, Between the Years 1566 and 1698, Together with an Index of Names. Mitchell and Hughes. p. 130.

- ^ Hasler, P. W., HoP: House of Commons 1558–1603, HMSO 1981, pp. 421–4 [Bells second oration.] – Trinity Dublin, Thomas Cromwell's jnl. citing the following: a: The provisions of Merton (1236) the comprehensive statute setting out the law on land tenure, baronial rights etc. b: The statute of Marlborough (1267) of similar content. c: The statute of Mortmain (1279) which restricted grants to religious foundations. d: The statute of Winchester, crucial in the history of criminal law. e: The statute of Merchants (1285), which clarified the statute of Acton Burnell (1283) devised to meet the grievances of merchants who found it difficult to collect their debts. f: The Articles of the Clergy (1315) . g: A reference to clause 14 of 4 Ed. III (1330) to this effect. The statute fell into desuetude after the 1340s. [1]

- ^ O'Donoghue, M.P.D., Transcription Report, The National Archives, UK, Catalog Reference Prob. 11/59, Image Reference 364 (C)

- ^ Joseph Jackson Howard, Frederick Arthur Crisp (1905). Visitation of England and Wales. p. 110.

- ^ "Townley, Richard Greaves (1786-1855), of Fulbourn, Cambs. and Beaupré Hall, Norf., History of Parliament Online". www.histparl.ac.uk.

- ^ Hussey, C., Beaupre Hall Wisbech, Coventry Homes and Gardens Old & New, pb. Country Life, 1923

- ^ Coll Arm Ms, The Visitations of Norfolk, 1563, William Hervey 1589, Robert Cooke and 1613, John Raven, pp. 33–34 Bell. Beaupre., Ed. Walter Rye, London 1891

- ^ a b O'Donoghue, M.P.D., Transcription Report, The National Archives, UK, Catalog Reference Prob. 11/51, Image Reference 18, (C)Crown Copyright

- ^ Hasler, P. W., HoP: House of Commons 1558–1603, HMSO 1981, pp. 421–4 [Bells second oration.] – Trinity Dublin, Thomas Cromwell's jnl. citing the following: a: The provisions of Merton (1236) the comprehensive statute setting out the law on land tenure, baronial rights etc. b: The statute of Marlborough (1267) of similar content. c: The statute of Mortmain (1279) which restricted grants to religious foundations. d: The statute of Winchester, crucial in the history of criminal law. e: The statute of Merchants (1285), which clarified the statute of Acton Burnell (1283) devisied to meet the grievances of merchants who found it difficult to collect their debts. f: The Articles of the Clergy (1315) . g: A reference to clause 14 of 4 Ed. III (1330) to this effect. The statute fell into desuetude. [2]

- ^ The National Archives, UK, Catalog Reference Prob. 11/111, Image Reference 565 (C)

- ^ Kupperman, K., Puritan Colonization from Providence Island through the Western Design, The William and Mary "Queens' College Cambridge - Fellows & Presidents 1448-1599". Archived from the original on 10 August 2007. Retrieved 24 July 2007.

- ^ Hunstanton Parish Registers - Norfolk Record Office

- ^ Outwell Parish Registers

- ^ Woodcock, T., and, Robinson, J. M.,Heraldry in Historic Houses of Great Britain, The National Trust, pb. 2000 [3]

- ^ MacDonald, W., Documentary source book of American History, 1606–1913,1910-20-21 [4]

- ^ Salt, S. P., 'Dering, Sir Edward, first baronet (1598–1644)’, ODNB, OUP, 2004 accessed 23 May 2005

External links

[edit]- NPG, London. (1) Robert Bell, Esq., Speaker 1572, possibly by the artist T. Athlow, (2) Sir Robert Bell, Chief Baron of the Exchequer 1577, by William Camden Edwards, after unknown artist, and the British Museum [6]

- Hutchinson, John (1902). . A catalogue of notable Middle Templars, with brief biographical notices (1 ed.). Canterbury: the Honourable Society of the Middle Temple. p. 17.