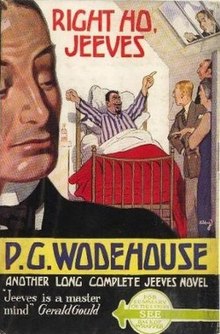

Right Ho, Jeeves

First edition | |

| Author | P. G. Wodehouse |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Series | Jeeves |

| Genre | Comic novel |

| Publisher | Herbert Jenkins |

Publication date | 1934 |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) |

| Pages | 248 |

| Preceded by | Thank You, Jeeves |

| Followed by | The Code of the Woosters |

Right Ho, Jeeves is a novel by P. G. Wodehouse, the second full-length novel featuring the popular characters Jeeves and Bertie Wooster, after Thank You, Jeeves. It was first published in the United Kingdom on 5 October 1934 by Herbert Jenkins, London, and in the United States on 15 October 1934 by Little, Brown and Company, Boston, under the title Brinkley Manor.[1] It had also been sold to the Saturday Evening Post, in which it appeared in serial form from 23 December 1933 to 27 January 1934, and in England in the Grand Magazine from April to September 1934.[2] Wodehouse had already started planning this sequel while working on Thank You, Jeeves.[3]

The story is mostly set at Brinkley Court, the home of Bertie's Aunt Dahlia, and introduces the recurring characters Gussie Fink-Nottle and Madeline Bassett. Bertie's friend Tuppy Glossop and cousin Angela Travers also feature in the novel, as does Brinkley Court's prized chef, Anatole.

Plot

[edit]Bertie returns to London from several weeks in Cannes spent in the company of his Aunt Dahlia Travers, her daughter Angela and her soppy, childish friend Madeline Bassett. In Bertie's absence, Jeeves has been advising Bertie's old school friend, Gussie Fink-Nottle, a shy teetotaller with a passion for newts and a face like a fish, who is in love with Madeline but is too timid to propose. Jeeves advises Gussie attend a fancy-dress ball (at Madeline’s invitation) dressed as Mephistopheles which Jeeves believes will give Gussie the confidence to confess his love. This plan fails, because of Gussie's excessive goofiness. Owing to a strong disagreement about Bertie’s new mess jacket, Bertie harshly blames Jeeves for Gussie’s failure and tells him not to offer any more advice to him.

Gussie, though initially disturbed to hear Jeeves is no longer advising him, cheers up when Bertie tells him that Brinkley Court, where Madeline is staying, is also the country seat of Bertie's Aunt Dahlia and Uncle Tom, and that he (Bertie) can easily get him (Gussie) an invitation to join her there. It happens that Aunt Dahlia had demanded that Bertie come to Brinkley Court to make a speech and present the school prizes to students at the local grammar school. Determined to avoid this task and to assist Gussie's wooing, Bertie sends Gussie to Brinkley Court in his place where he will have the chance to get close to Madeline, and also be forced to distribute the school prizes instead of himself. Aunt Dahlia begrudgingly agrees to this.

When Bertie hears that Angela has broken off her engagement to Tuppy Glossop, he feels obliged to go down to Brinkley Court himself, to comfort Aunt Dahlia. In addition to her worrying about Angela's broken engagement, Aunt Dahlia is anxious because she has lost £500 gambling at Cannes, and now needs to ask her miserly husband Tom to replace the money in order to keep financing her magazine, Milady's Boudoir. Bertie takes umbrage when Aunt Dahlia says the only reason she’s grateful Bertie came is because he brought Jeeves. When Bertie tries to offer her advice she vigorously refuses to let him speak. Bertie finds Tuppy in the grounds who tells him he and Angela fell out due to Angela saying he was getting fat and Tuppy not believing she was attacked by a shark in Cannes. Bertie advises Tuppy to regain Angela's sympathy by refusing his dinner. He offers similar advice to Gussie, to show his love for Madeline and to Aunt Dahlia to arouse Uncle Tom’s sympathy. All take his advice; however, neither Angela, nor Madeline nor Tom notice, and the resulting return of plates of untasted food severely upsets Aunt Dahlia's temperamental prized French chef Anatole, who gives notice to quit. Aunt Dahlia understandably blames Bertie for this disaster.

Gussie still cannot confess his love to Madeline, so Bertie invites her for a walk to soften her up for him. Unfortunately she misinterprets his words as a marriage proposal on his own behalf. To his relief, she tells Bertie she cannot marry him, as she has fallen in love with Gussie. Bertie relays the good news to Gussie, but even with this encouragement, Gussie remains too timid to propose. Bertie decides to embolden him by lacing his orange juice with brandy.

More and more, it was beginning to be borne in upon me what a particularly difficult chap Gussie was to help. He seemed to so marked an extent to lack snap and finish. With infinite toil, you manoeuvred him into a position where all he had to do was charge ahead, and he didn't charge ahead, but went off sideways, missing the objective completely.

— Bertie learns from Jeeves that Gussie lost his nerve[4]

Gussie ends up imbibing many times more brandy than Bertie had intended. Under its influence, Gussie successfully proposes to Madeline. He then presents the prizes to the schoolboys, with a drunken speech, berating the staff and pupils. Madeline, disgusted, breaks the engagement. Heartbroken and still drunk, Gussie proposes to Angela in order to score off Madeline; Angela accepts his proposal in order to score off Tuppy. Tuppy's jealousy is aroused and he chases Gussie all around the mansion, vowing to beat him within an inch of his life. Madeline tells Bertie she will marry him instead of Gussie. The prospect of spending his life with the drippy Madeline appalls Bertie, but his personal code of chivalry will not allow him to insult her by withdrawing his "proposal" and turning her down.

Helpless in the face of all this chaos, Bertie appeals to Jeeves for advice. Jeeves suggests that Bertie ring the fire bell at midnight so Gussie and Tuppy will respectively rescue Madeline and Angela. Although skeptical, Bertie follows this advice. However, when all the residents have evacuated the building, none of the estranged couples appear reconciled. When they try to return to bed, they find that all the doors are locked; no one has the keys, and all staff members away at a dance. Naturally, Bertie is blamed for the group being forced to spend the rest of the night outside. Jeeves suggests that Bertie ride a bicycle to the staff dance to retrieve the key from the butler. Bertie initially refuses but is forced by Aunt Dahlia. Bertie cycles the nine miles to the dance only to be told by the butler that he left the keys with Jeeves. Furious at having taken a long, dangerous ride in the dark, Bertie returns to Brinkley Court, and finds that Madeline and Gussie have made up, Angela and Tuppy have also made up, Anatole has withdrawn his notice and agreed to stay on, and Uncle Tom has agreed to lend Aunt Dahlia the £500 she needs. Jeeves explains that his true plan was to unite all the estranged parties in their contempt for Bertie by forcing them so spend the night outside and then in their collective amusement by finding the keys just after Bertie left, thus making his journey pointless. Though tired and aching, Bertie cannot argue with the results. Jeeves then says that he accidentally burned Bertie's mess jacket. Bertie is incensed, but agrees to let Jeeves have his way.

I climbed into bed and sank back against the pillows. I must say that my generous wrath had ebbed a bit. I was aching the whole length of my body, particularly toward the middle, but against this you had to set the fact that I was no longer engaged to Madeline Bassett. In a good cause one is prepared to suffer. Yes, looking at the thing from every angle, I saw that Jeeves had done well, and it was with an approving beam that I welcomed him as he returned with the needful.

He did not check up with this beam. A bit grave, he seemed to me to be looking, and I probed the matter with a kindly query:

“Something on your mind, Jeeves?”

“Yes, sir. I should have mentioned it earlier, but in the evening’s disturbance it escaped my memory, I fear I have been remiss, sir.”

“Yes, Jeeves?” I said, champing contentedly.

“In the matter of your mess-jacket, sir.”

A nameless fear shot through me, causing me to swallow a mouthful of omelette the wrong way.

“I am sorry to say, sir, that while I was ironing it this afternoon I was careless enough to leave the hot instrument upon it. I very much fear that it will be impossible for you to wear it again, sir.”

One of those old pregnant silences filled the room.

“I am extremely sorry, sir.”

For a moment, I confess, that generous wrath of mine came bounding back, hitching up its muscles and snorting a bit through the nose, but, as we say on the Riviera, à quoi sert-il? There was nothing to be gained by g.w. now.

We Woosters can bite the bullet. I nodded moodily and speared another slab of omelette.

“Right ho, Jeeves.”

“Very good, sir.”

— The closing bit of dialogue[5]

Style

[edit]Like the preceding novel Thank You, Jeeves, Right Ho, Jeeves uses Bertie's rebellion against Jeeves to create strong plot conflict that is sustained through most of the story. Writer Kristin Thompson refers to these two novels as Bertie's "rebellious period", which ends when Jeeves reasserts his authority at the end of Right Ho, Jeeves. This period serves as a transition between the sustained action of the short stories and the later Jeeves novels, which generally use a more episodic problem-solution structure.[6]

While Edwardian elements persist in Wodehouse's stories, for instance the popularity of gentlemen's clubs like the Drones Club, there are nevertheless references to contemporary events, as with a floating timeline. For example, in Right Ho, Jeeves, chapter 17, Bertie makes a contemporary reference to nuclear fission experiments:

I was reading in the paper the other day about those birds who are trying to split the atom, the nub being that they haven't the foggiest as to what will happen if they do. It may be all right. On the other hand, it may not be all right. And pretty silly a chap would feel, no doubt, if having split the atom he suddenly found the house going up in smoke and himself being torn limb from limb.[7]

When stirred, Bertie Wooster sometimes unintentionally employs spoonerisms, as he does in chapter 12: "Tup, Tushy!—I mean, Tush, Tuppy!".[8] Bertie occasionally uses a transferred epithet, using an adjective to modify a noun rather than using the corresponding adverb to modify the verb of the sentence, as in the following quote in chapter 17: "It was the hottest day of the summer, and though somebody had opened a tentative window or two, the atmosphere remained distinctive and individual".[9]

Wodehouse often uses popular detective story clichés out of place for humorous effect, as in chapter 15: "Presently from behind us there sounded in the night the splintering crash of a well-kicked plate of sandwiches, accompanied by the muffled oaths of a strong man in his wrath".[10]

Wodehouse frequently uses horse racing as a source of imagery. For example, Bertie describes how he, his Aunt Dahlia, and the butler Seppings rush to Anatole's room in chapter 20 in a parody of race-reporting. For instance, Bertie remarks that "I put down my plate and hastened after her, Seppings following at a loping gallop" and that at the top of the first flight of stairs, Aunt Dahlia "must have led by a matter of half a dozen lengths, and was still shaking off my challenge when she rounded into the second".[11]

The humour in the speech of Aunt Dahlia's French cook Anatole comes from the combination of informal British and American expressions with real or imaginary loan translations from French. The most extensive example of Anatole's speech is his diatribe in chapter 20. To quote part of his speech: "Hot dog! You ask me what is it? Listen. Make some attention a little. Me, I have hit the hay, but I do not sleep so good, and presently I wake and up I look, and there is one who makes faces against me through the dashed window".[12] Anatole is similar to Jeeves, being a highly competent servant whose loss is a constant threat, though Anatole, while mentioned frequently, does not make an appearance in any other story; this distance differentiates him from Jeeves.[13]

Jeeves sometimes denigrates Bertie in ways which are too subtle for Bertie to perceive, but obvious to readers. For example, in chapter 3, when Bertie is puzzled after Aunt Dahlia invites him to Brinkley Court, since he has just spent a two-month vacation with her. Bertie says to Jeeves:

"But why, Jeeves? Dash it all, she's just had nearly two months of me."

"Yes, sir."

"And many people consider the medium dose for an adult two days."

"Yes, sir. I appreciate the point you raise. Nevertheless, Mrs. Travers appears very insistent."

Jeeves's reply, "I appreciate the point you raise", carries an irony that Bertie apparently misses. However, since Jeeves invariably stays in Bertie's employ, the quote suggests that Jeeves puts up with and even enjoys Bertie's continuing society more than Bertie's friends and relatives do.[14]

In the novel, Aunt Dahlia uses the expression "oom beroofen", which is derived from the German "unberufen" and means "touch wood" or "knock on wood". Wodehouse previously used "beroofen" in The Gem Collector (1909).[15]

Background

[edit]The book is dedicated to Raymond Needham KC, "with affection and admiration". Needham had represented Wodehouse in a tax dispute case and won the case. According to Wodehouse scholar Richard Usborne, Needham had to talk Wodehouse out of using the original, more provocative dedication: "To Raymond Needham KC, who put the tax-gatherers to flight when they had their feet on my neck and their hands in my wallet" or words to that effect. Wodehouse actually befriended the tax inspector involved in the case.[16]

Publication history

[edit]In the Saturday Evening Post, the story was illustrated by Henry Raleigh.[17] The story was later printed in Men Only in April 1936.[18] Along with The Inimitable Jeeves and Very Good, Jeeves, the novel was included in a collection titled Life With Jeeves, published in 1981 by Penguin Books.[19]

Reception

[edit]- The Times (5 October 1934): "On the principle that 'spilt milk blows nobody any good,' Wooster, as usual, spills a few additional gallons of the milk of human imbecility, and awaits the consequences... When, at last, Jeeves clocks in, having resolved the initial discord to his own satisfaction, the young master pays the customary penalty for his good intentions—on this occasion a wholly futile bicycle ride of 18 miles in the dark. When he returns, Jeeves has done the trick, the place is stiff with happy endings, and Mr. Wodehouse has shown once again that all is for the funniest in the most ludicrous of worlds".[20]

- Gerald Gould, The Observer (21 October 1934): "Of the immortal Mr. Wodehouse, creator of the immortal Jeeves, it remains only to say the ever-incredible and ever-true—'He gets better and better.' Whereas one used to smile, one now rocks and aches with laughter. Right Ho, Jeeves is, in the phrase its author applies to a mess jacket, 'one long scream from start to finish'".[21]

- New York Times Book Review (28 October 1934): "Jeeves and Bertie Wooster here show up at their balmiest and best. Not to put too fine a point on the matter, Brinkley Manor is an authentic triumph, in the master's best manner... The hilarious Wooster thought, on the occasion this story celebrates, that Jeeves (first gentleman among the world's gentlemen's gentlemen) had sprained his brain. So he took a turn at straightening out people's lives... Fortunately, Jeeves went along too. As a matchmaker Bertie was industrious but terrible".[22]

- In 1996, John Le Carré listed the work among his all-time favourite novels, stating: "No library, however humble, is complete without its well-thumbed copy of Right Ho, Jeeves, by P.G. Wodehouse, which contains the immortal scene of Gussie Fink-Nottle, drunk to the gills, presenting the prizes to the delighted scholars of Market Snodsbury Grammar School".[23]

- Stephen Fry, in an article titled "What ho! My hero, PG Wodehouse" (18 January 2000), remarks on the popularity of the work, especially the prize-giving episode: "The masterly episode where Gussie Fink-Nottle presents the prizes at Market Snodsbury grammar school is frequently included in collections of great comic literature and has often been described as the single funniest piece of sustained writing in the language. I would urge you, however, to head straight for a library or bookshop and get hold of the complete novel Right Ho, Jeeves, where you will encounter it fully in context and find that it leaps even more magnificently to life."[24] In late 2020, Fry would narrate the book and four others in a Jeeves audiobook for Audible.

- Richard Usborne, in his book Plum Sauce: A P. G. Wodehouse Companion (2003), states that "the prize-giving is a riot, probably the best-sustained and most anthologised two chapters of Wodehouse".[25]

- In a 2009 internet poll, Right Ho, Jeeves was voted number one in the "best comic book by English writer" category.[26]

- In July 2012, Christian Science Monitor editors Peder Zane and Elizabeth Drake listed Right Ho, Jeeves as number ten in a list of the ten best comic works in all of literature.[27]

Adaptations

[edit]Television

[edit]The story was adapted into the Jeeves and Wooster episodes "The Hunger Strike"[28] and "Will Anatole Return to Brinkley Court?", which first aired on 13 May 1990 and 20 May 1990.[29] There are some changes, including:

- In the original story, Jeeves' initially suggests Gussie gain the courage to propose to Madeline by dressing as Mephistopheles. The party invite subplot was removed from the TV series, but the costume later appears in "The Bassetts' Fancy Dress Ball".

- In the original story, Tom Travers has a pistol, which is never fired; in the first episode, he has a shotgun, which Bertie accidentally fires at a chandelier, after which Aunt Dahlia tells Bertie to go home. He returns to Brinkley Court in the following episode.

- Anatole leaves Brinkley Court between the two episodes, and Jeeves is sent to convince him to return.

- In the episode, Bertie does not find out that Jeeves spiked Gussie's drink until after he himself has done so.

- In the original story, Gussie eventually chooses to drink alcohol, and also unknowingly drinks the spiked orange juice; in the episode, he only drinks the spiked orange juice.

- While running away from Tuppy in the episode, Gussie does not end up on the roof, a scene depicted in the first edition cover artwork.

- In the original story, Bertie was obliged to ride his bicycle at night without a lamp, and it was not raining; in the episode, he has a lamp, but it is raining heavily.

Radio

[edit]In the 1956 BBC Light Programme dramatisation of the novel, Deryck Guyler portrayed Jeeves and Naunton Wayne portrayed Bertie Wooster.[30]

Right Ho, Jeeves was adapted into a radio drama in 1973 as part of the series What Ho! Jeeves starring Michael Hordern as Jeeves and Richard Briers as Bertie Wooster.[31]

BBC radio adapted the story for radio again in 1988. David Suchet portrayed Jeeves and Simon Cadell portrayed Bertie Wooster.[32]

References

[edit]- Notes

- ^ McIlvaine, E; Sherby, L S; Heineman, J H (1990). P.G. Wodehouse: A comprehensive bibliography and checklist. New York: James H Heineman. pp. 66–68. ISBN 087008125X.

- ^ Taves, Brian; Briers, Richard (2006). P.G. Wodehouse and Hollywood: screenwriting, satires, and adaptations. McFarland. p. 191. ISBN 978-0-7864-2288-3.

- ^ Jasen, David A (2002). P.G. Wodehouse: a portrait of a master. Music Sales Group. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-8256-7275-0.

- ^ Wodehouse (2008) [1934], chapter 11, p. 136.

- ^ "Right Ho, Jeeves".

- ^ Thompson (1992), pp. 234–247.

- ^ French, R B D (1966). P. G. Wodehouse. Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd. p. 73.

- ^ Hall (1974), p. 83.

- ^ Hall (1974), p. 86.

- ^ Hall (1974), p. 113.

- ^ Hall (1974), p. 110.

- ^ Hall (1974), pp. 98–99.

- ^ Thompson (1992), pp. 139–140.

- ^ Thompson (1992), p. 145.

- ^ Wodehouse, P G (2013). Ratcliffe, Sophie (ed.). P. G. Wodehouse: A Life in Letters. W W Norton & Company. p. 68. ISBN 978-0786422883.

- ^ Phelps, Barry (1992). P. G. Wodehouse: Man and Myth. London: Constable and Company. p. 189. ISBN 009471620X.

- ^ McIlvaine (1990), p. 157, D59.88-D59.93.

- ^ McIlvaine (1990), p. 173, D109.1.

- ^ McIlvaine (1990), p. 126, B24a.

- ^ "New Novels". The Times. London. 5 October 1934. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ^ Gould, Gerald (21 October 1934). "New Novels". The Observer. London. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ "The Perennial Jeeves". The New York Times. New York. 28 October 1934. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ^ Le Carré, John (30 September 1996). "Personal Best: Right Ho, Jeeves". Salon.com. Retrieved 30 May 2012.

- ^ Fry, Stephen (18 January 2000). "What ho! My hero, PG Wodehouse". The Independent. Archived from the original on 19 August 2002. The complete version of this article appears as the introduction to What Ho! The Best of PG Wodehouse (2000).

- ^ Usborne, Richard (2003). Plum Sauce: A P. G. Wodehouse Companion. New York: The Overlook Press. p. 170. ISBN 1-58567-441-9.

- ^ Arnold, Sue (28 August 2009). "Right Ho, Jeeves by PG Wodehouse". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- ^ Drake, Elizabeth; Zane, Peder (12 July 2012). "10 best comic works in literature". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- ^ "Jeeves and Wooster Series 1, Episode 4". British Comedy Guide. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- ^ "Jeeves and Wooster Series 1, Episode 5". British Comedy Guide. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- ^ "Three Star Bill Drama: Naunton Wayne with Deryck Guyler and Richard Wattis in ' Right Ho, Jeeves'". BBC Light Programme. Radio Times Genome. 3 June 1956. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- ^ Taves, p. 128.

- ^ "Saturday-Night Theatre: Right Ho, Jeeves". BBC Radio 4. Radio Times Genome. 29 August 1988. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- Bibliography

- Cawthorne, Nigel (2013). A Brief Guide to Jeeves and Wooster. London: Constable & Robinson. ISBN 978-1-78033-824-8.

- Hall, Robert A Jr (1974). The Comic Style of P. G. Wodehouse. Hamden: Archon Books. ISBN 0-208-01409-8.

- McIlvaine, Eileen; Sherby, Louise S; Heineman, James H (1990). P.G. Wodehouse: A Comprehensive Bibliography and Checklist. New York: James H Heineman. ISBN 978-0-87008-125-5.

- Taves, Brian (2006). P.G. Wodehouse and Hollywood. London: McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-2288-3.

- Thompson, Kristin (1992). Wooster Proposes, Jeeves Disposes or Le Mot Juste. New York: James H Heineman. ISBN 0-87008-139-X.

- Wodehouse, P G (2008) [1934]. Right Ho, Jeeves (Reprinted ed.). London: Arrow Books. ISBN 978-0099513742.

- Wodehouse, P G; Fry, Stephen (2011) [2000]. What Ho! The Best of Wodehouse. Arrow. ISBN 978-0099551287.

External links

[edit]- Right Ho, Jeeves at Standard Ebooks

- Kuzmenko, Michel. "Right Ho, Jeeves". The Russian Wodehouse Society.

- Right Ho, Jeeves.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)  Right Ho, Jeeves public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Right Ho, Jeeves public domain audiobook at LibriVox