Ricardo Alarcón

Ricardo Alarcón | |

|---|---|

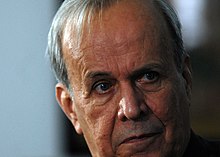

Alarcón in 2008 | |

| President of the National Assembly of People's Power | |

| In office 24 February 1993 – 24 February 2013 | |

| Vice President | Jaime Alberto Hernandez-Baquero Crombet |

| Preceded by | Juan Escalona Reguera |

| Succeeded by | Esteban Lazo |

| Minister of Foreign Affairs | |

| In office 1992–1993 | |

| Premier | Fidel Castro |

| Preceded by | Isidoro Malmierca Peoli |

| Succeeded by | Roberto Robaina |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Ricardo Alarcón de Quesada 21 May 1937 Havana, Cuba |

| Died | 30 April 2022 (aged 84) Havana, Cuba |

| Political party | Communist Party of Cuba |

| Profession | Civil servant |

Ricardo Alarcón de Quesada (21 May 1937 – 30 April 2022) was a Cuban politician. He served as his country's Permanent Representative to the United Nations (UN) for nearly 30 years and later served as Minister of Foreign Affairs from 1992 to 1993. Subsequently, Alarcón was President of the National Assembly of People's Power from 1993 to 2013, and because of this post, was considered the third-most powerful figure in Cuba.[1] He was also until 2013 a Member of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Cuba.[2]

A graduate of the University of Havana with a doctorate in philosophy, he served in various diplomatic posts following the Cuban Revolution. His first foreign-policy post was Head of the Americas Division in Cuba's Foreign Ministry. During his tenure as Permanent Representative to the United Nations, Alarcón held several prominent offices, such as President of the Security Council and Vice-President of the General Assembly.

Early life

[edit]Alarcón was born in Havana on 21 May 1937. He entered the University of Havana in 1954 and graduated with a degree as a Doctor of Philosophy and Humanities.[3] Alarcón became active in the Federation of University Students (FEU), serving as the secretary of culture for the FEU from 1955 to 1956. Alarcón became active in Castro's 26th of July Movement, which was attempting to oust President Fulgencio Batista, in July 1955. Alarcón assisted in the organization of the student apparatus of the guerrilla organization's youth brigade. Alarcón was elected the FEU's Vice President in 1959, and served as the President of the Student Organization from 1961 to 1962. However, unlike the Castros, Alarcón was active in the urban underground resistance, and not the guerrilla movement located in the countryside.[4]

In 1962, the new Castro-led government appointed Alarcón as the Director of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs' Americas division, where he began his diplomatic career. Between 1966 and 1978, he served as Permanent Representative of Cuba to the United Nations, Vice-President of the General Assembly of the United Nations, President of the Council of Administration to the United Nations Development Programme, and Vice-President of the United Nations Committee on the Exercise of the Inalienable Rights of the Palestinian People. In 1978, Alarcón was promoted to first vice-minister of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.[5] While serving as Permanent Representative to the UN for a second time, Alarcón was President of the Security Council in February 1990 and July 1991.[6] In 1992, he was made Minister of Foreign Affairs, and in February 1993, he became the President of the National Assembly.[5]

Career

[edit]President of the National Assembly (1993–2013)

[edit]Alarcón took over the office of President of the National Assembly of People's Power in 1993 in what Ben Corbett, a historian, considered a "demotion" from his earlier post as Minister of Foreign Affairs.[7] However, William E. Ratliff and Roger W. Fontaine, in their book, A Strategic Flip-flop in the Caribbean: Lift the Embargo on Cuba, ranks Alarcón as having been the third-most powerful figure in Cuba.[8]

One year after taking office, Alarcón travelled to the United States as the head of a five-member delegation to talk about the migration issues between the two countries. In a government statement, Alarcón was described as the "best qualified" to deal with such delicate issues as emigration, and his knowledge of the "fundamental causes" to mass emigration from Cuba. Alarcón, along with the Cuban government, believed that the United States economic embargo against Cuba was the main culprit for mass emigration from the country.[9] The negotiations were suspended for a while when he abruptly travelled to Cuba to discuss the situation with the Cuban government.[10] After his abrupt return trip to Cuba, he came back to the United States and continued the negotiations. When he returned to the United States, he was more positive in tone, and several Cuban officials told the media that an agreement could be reached.[11] Alarcón was able to reach an agreement with the United States Government on 9 September 1994, and the United States promised to issue at least 20,000 immigrant visas a year for Cuban citizens seeking to leave their homeland.[12]

In August 2000, Alarcón was involved in a minor dispute with the United States when he was denied a visa to attend an international conference in New York City. Alarcón lived in Manhattan for over twelve years, but because of his status as a Cuban government official, he was only allowed within a 25-mile radius of the United Nations.[13]

On 2 December 2003, United States Under Secretary for Arms Control and International Security John R. Bolton charged that Cuba, along with Iran, North Korea, Syria, and Libya, were "rogue states...whose pursuit of weapons of mass destruction makes them hostile to U.S. interests [and who] will learn that their covert programs will not escape either detection or consequences." In response, Alarcón called Bolton "a liar" and cited U.S. claims pertaining to Iraq's weapons of mass destruction in justification of the Iraq War which were later found to be incorrect.[14]

In 2006, Alarcón stated: "At some moment, US rhetoric changed to talk of democracy... For me, the starting point is the recognition that democracy should begin with Pericles's definition – that society is for the benefit of the majority – and should not be imposed from outside."[15] During Fidel Castro's transfer of presidential duties to his brother Raúl Castro, Alarcón told the foreign media that Fidel would be fit to run for re-election to the assembly in January 2008 parliamentary election.[16] However, in an interview with the CNN, Alarcón said he was unsure if Fidel would accept the post or not.[17] Alarcón, in an interview on the topic on who would succeed Fidel Castro, said; "All those who have been trying to fool the world and put out the idea that something terrible would happen in Cuba, that people would take to the streets, that there would be great instability, the door slammed on them and they must have very swollen hands now".[18]

Later life and death

[edit]Alarcón was married to Margarita Perea Maza. She died on 9 February 2008.[19] Alarcón died at the age of 84 on 30 April 2022, his family confirmed. No cause of death was immediately given.[20]

References

[edit]- ^ "Cuba parliament opens as Fidel Castro visits". BBC World Service. 24 February 2013. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- ^ "Cuba removes Ricardo Alarcon from top Communist body". BBC News. 3 July 2013. Retrieved 19 June 2024.

- ^ Lamrani, Salim; Alarcón, Ricardo (2005). United States Against Cuba: The War on Terrorism and the Five Case. Editorial El Viejo Topo. p. 197. ISBN 978-84-96356-37-5.

- ^ Bardach, Ann Louise (2009). Without Fidel: A Death Foretold in Miami, Havana, and Washington. Vol. 3. Simon & Schuster. p. 205. ISBN 978-1-4165-5150-8.

- ^ a b Profile at Cuban parliament website (in Spanish).

- ^ "Presidents of the Security Council : 1990-1999" Archived 18 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine, UN.org.

- ^ Corbett, Ben (2004). This Is Cuba: An Outlaw Culture Survives. Basic Books. p. 256. ISBN 978-0-8133-4224-5.

- ^ Ratliff, William E.; Fontaine, Roger W. (2000). A Strategic Flip-flop in the Caribbean: Lift the Embargo on Cuba. Hoover Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-8179-4352-3.

- ^ Staff writer (31 August 1994). "Flight from Cuba; Cuba Names Leader For Talks With U.S." The New York Times. New York City, New York. Retrieved 17 February 2011.

- ^ Lewis, Paul (8 September 1994). "U.S.-Cuban Talks Suspended As Envoy Returns to Havana". The New York Times. New York City, New York. Retrieved 17 February 2011.

- ^ Golden, Tim (9 September 1994). "Cuba, in Shift, Says Deal Can Be Reached With the U.S." The New York Times. New York City, New York. p. 1. Retrieved 17 February 2011.

- ^ Golden, Tim (22 September 1994). "Cuban Official Criticizes Lag By the U.S. in Issuing Visas". The New York Times. New York City, New York. Retrieved 17 February 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (29 August 2000). "Cuban politician denied US visa". London, United Kingdom: BBC Online. Retrieved 17 February 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (31 December 2003). "Cuban leader sees invasion risk as 'real'". The New York Times. New York City, New York. Retrieved 17 February 2011.

- ^ Campbell, Duncan (3 August 2006). "Propaganda war grips a land crippled by shortages". The Guardian. London, United Kingdom. Retrieved 17 February 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (15 March 2007). "Castro 'to be fit to hold power'". London, United Kingdom: BBC Online. Retrieved 17 February 2011.

- ^ Lacey, Marc (23 January 2008). "The Americas; Cuba: Will Castro Return?". The New York Times. New York City, New York. Retrieved 17 February 2011.

- ^ Miller, Jimmy (8 August 2008). "Succession talk fuels the Cuban rumour mill". The Telegraph. London, United Kingdom. Retrieved 17 February 2011.

- ^ The Miami Herald; "Wife of Cuban Official Dies After Long Illness"; 12 February 2008, Page 7A

- ^ "Ricardo Alarcón, key player in Cuba-U.S. relations, dies at 84". NBC News.

Further reading

[edit]- Ricardo Alarcón and Reinaldo Suarez, Cuba y Su Democracia (Editorial de Ciencias Sociales 2004) ISBN 987-1158-06-8

- Fidel Castro and Ricardo Alarcón, EE.UU. fuera del oriente medio (Pathfinder Press 2001) ISBN 0-87348-625-0

- Ricardo Alarcón and Mary Murray, Cuba and the United States: an interview with Cuban Foreign Minister, Ricardo Alaron (Ocean Press 1992) ISBN 1-875284-69-9

External links

[edit]- Ricardo Alarcón Archive at marxists.org

- Official Biography – Cuban Communist Party

- Official Biography – Cuban National Assembly

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- 1937 births

- 2022 deaths

- 20th-century Cuban politicians

- 21st-century Cuban politicians

- Communist Party of Cuba politicians

- Cuban diplomats

- Cuban revolutionaries

- Foreign ministers of Cuba

- Politicians from Havana

- People of the Cuban Revolution

- Permanent Representatives of Cuba to the United Nations

- Presidents of the National Assembly of People's Power