Kidney

| Kidneys | |

|---|---|

The kidneys lie in the retroperitoneal space behind the abdomen, and act to filter blood to create urine | |

Location of kidneys with associated organs (adrenal glands and bladder) | |

| Details | |

| System | Urinary system and endocrine system |

| Artery | Renal artery |

| Vein | Renal vein |

| Nerve | Renal plexus |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | ren |

| Greek | νεφρός (nephros) |

| MeSH | D007668 |

| TA98 | A08.1.01.001 |

| TA2 | 3358 |

| FMA | 7203 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

In humans, the kidneys are two reddish-brown bean-shaped blood-filtering organs[1] that are a multilobar, multipapillary form of mammalian kidneys, usually without signs of external lobulation.[2][3] They are located on the left and right in the retroperitoneal space, and in adult humans are about 12 centimetres (4+1⁄2 inches) in length.[4][5] They receive blood from the paired renal arteries; blood exits into the paired renal veins. Each kidney is attached to a ureter, a tube that carries excreted urine to the bladder.

The kidney participates in the control of the volume of various body fluids, fluid osmolality, acid-base balance, various electrolyte concentrations, and removal of toxins. Filtration occurs in the glomerulus: one-fifth of the blood volume that enters the kidneys is filtered. Examples of substances reabsorbed are solute-free water, sodium, bicarbonate, glucose, and amino acids. Examples of substances secreted are hydrogen, ammonium, potassium and uric acid. The nephron is the structural and functional unit of the kidney. Each adult human kidney contains around 1 million nephrons, while a mouse kidney contains only about 12,500 nephrons. The kidneys also carry out functions independent of the nephrons. For example, they convert a precursor of vitamin D to its active form, calcitriol; and synthesize the hormones erythropoietin and renin.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) has been recognized as a leading public health problem worldwide. The global estimated prevalence of CKD is 13.4%, and patients with kidney failure needing renal replacement therapy are estimated between 5 and 7 million.[6] Procedures used in the management of kidney disease include chemical and microscopic examination of the urine (urinalysis), measurement of kidney function by calculating the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) using the serum creatinine; and kidney biopsy and CT scan to evaluate for abnormal anatomy. Dialysis and kidney transplantation are used to treat kidney failure; one (or both sequentially) of these are almost always used when renal function drops below 15%. Nephrectomy is frequently used to cure renal cell carcinoma.

Renal physiology is the study of kidney function. Nephrology is the medical specialty which addresses diseases of kidney function: these include CKD, nephritic and nephrotic syndromes, acute kidney injury, and pyelonephritis. Urology addresses diseases of kidney (and urinary tract) anatomy: these include cancer, renal cysts, kidney stones and ureteral stones, and urinary tract obstruction.[7]

The word “renal” is an adjective meaning “relating to the kidneys”, and its roots are French or late Latin. Whereas according to some opinions, "renal" should be replaced with "kidney" in scientific writings such as "kidney artery", other experts have advocated preserving the use of "renal" as appropriate including in "renal artery".[8]

Structure

In humans, the kidneys are located high in the abdominal cavity, one on each side of the spine, and lie in a retroperitoneal position at a slightly oblique angle.[9] The asymmetry within the abdominal cavity, caused by the position of the liver, typically results in the right kidney being slightly lower and smaller than the left, and being placed slightly more to the middle than the left kidney.[10][11][12] The left kidney is approximately at the vertebral level T12 to L3,[13] and the right is slightly lower. The right kidney sits just below the diaphragm and posterior to the liver. The left kidney sits below the diaphragm and posterior to the spleen. On top of each kidney is an adrenal gland. The upper parts of the kidneys are partially protected by the 11th and 12th ribs. Each kidney, with its adrenal gland is surrounded by two layers of fat: the perirenal fat present between renal fascia and renal capsule and pararenal fat superior to the renal fascia.

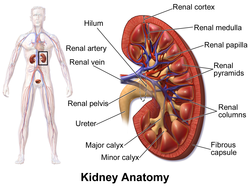

The human kidney is a bean-shaped structure with a convex and a concave border.[14] A recessed area on the concave border is the renal hilum, where the renal artery enters the kidney and the renal vein and ureter leave. The kidney is surrounded by tough fibrous tissue, the renal capsule, which is itself surrounded by perirenal fat, renal fascia, and pararenal fat. The anterior (front) surface of these tissues is the peritoneum, while the posterior (rear) surface is the transversalis fascia.

The superior pole of the right kidney is adjacent to the liver. For the left kidney, it is next to the spleen. Both, therefore, move down upon inhalation.

| Sex | Weight, standard reference range | |

| Right kidney | Left kidney | |

| Male[15] | 80–160 g (2+3⁄4–5+3⁄4 oz) | 80–175 g (2+3⁄4–6+1⁄4 oz) |

| Female[16] | 40–175 g (1+1⁄2–6+1⁄4 oz) | 35–190 g (1+1⁄4–6+3⁄4 oz) |

A Danish study measured the median renal length to be 11.2 cm (4+7⁄16 in) on the left side and 10.9 cm (4+5⁄16 in) on the right side in adults. Median renal volumes were 146 cm3 (8+15⁄16 cu in) on the left and 134 cm3 (8+3⁄16 cu in) on the right.[17]

Gross anatomy

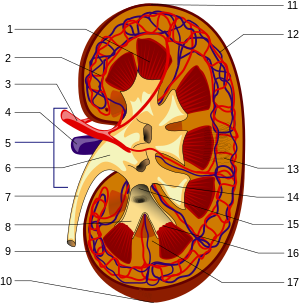

The functional substance, or parenchyma, of the human kidney is divided into two major structures: the outer renal cortex and the inner renal medulla. Grossly, these structures take the shape of eight to 18 cone-shaped renal lobes, each containing renal cortex surrounding a portion of medulla called a renal pyramid.[18] Between the renal pyramids are projections of cortex called renal columns.

The tip, or papilla, of each pyramid empties urine into a minor calyx; minor calyces empty into major calyces, and major calyces empty into the renal pelvis. This becomes the ureter. At the hilum, the ureter and renal vein exit the kidney and the renal artery enters. Hilar fat and lymphatic tissue with lymph nodes surround these structures. The hilar fat is contiguous with a fat-filled cavity called the renal sinus. The renal sinus collectively contains the renal pelvis and calyces and separates these structures from the renal medullary tissue.[19]

The kidneys possess no overtly moving structures.

-

Normal adult right kidney as seen on abdominal ultrasound with a pole to pole measurement of 9.34 cm

-

Image showing the structures that the kidney lies near

-

Cross-section through a cadaveric specimen showing the position of the kidneys

Blood supply

The kidneys receive blood from the renal arteries, left and right, which branch directly from the abdominal aorta. The kidneys receive approximately 20–25% of cardiac output in adult human.[18][20][21] Each renal artery branches into segmental arteries, dividing further into interlobar arteries, which penetrate the renal capsule and extend through the renal columns between the renal pyramids. The interlobar arteries then supply blood to the arcuate arteries that run through the boundary of the cortex and the medulla. Each arcuate artery supplies several interlobular arteries that feed into the afferent arterioles that supply the glomeruli.

Blood drains from the kidneys, ultimately into the inferior vena cava. After filtration occurs, the blood moves through a small network of small veins (venules) that converge into interlobular veins. As with the arteriole distribution, the veins follow the same pattern: the interlobular provide blood to the arcuate veins then back to the interlobar veins, which come to form the renal veins which exit the kidney.

Nerve supply

The kidney and nervous system communicate via the renal plexus, whose fibers course along the renal arteries to reach each kidney.[22] Input from the sympathetic nervous system triggers vasoconstriction in the kidney, thereby reducing renal blood flow.[22] The kidney also receives input from the parasympathetic nervous system,[23] by way of the renal branches of the vagus nerve; the function of this is yet unclear.[22][24] Sensory input from the kidney travels to the T10–11 levels of the spinal cord and is sensed in the corresponding dermatome.[22] Thus, pain in the flank region may be referred from corresponding kidney.[22]

Microanatomy

Nephrons, the urine-producing functional structures of the kidney, span the cortex and medulla. The initial filtering portion of a nephron is the renal corpuscle, which is located in the cortex. This is followed by a renal tubule that passes from the cortex deep into the medullary pyramids. Part of the renal cortex, a medullary ray is a collection of renal tubules that drain into a single collecting duct.[citation needed]

Renal histology is the study of the microscopic structure of the kidney. The adult human kidney contains at least 26 distinct cell types.[25] Distinct cell types include:

- Kidney glomerulus parietal cell

- Kidney glomerulus podocyte

- Kidney proximal tubule brush border cell

- Loop of Henle thin segment cell

- Thick ascending limb cell

- Kidney distal tubule cell

- Collecting duct principal cell

- Collecting duct intercalated cell

- Interstitial kidney cells

Gene and protein expression

In humans, about 20,000 protein coding genes are expressed in human cells and almost 70% of these genes are expressed in normal, adult kidneys.[26][27] Just over 300 genes are more specifically expressed in the kidney, with only some 50 genes being highly specific for the kidney. Many of the corresponding kidney specific proteins are expressed in the cell membrane and function as transporter proteins. The highest expressed kidney specific protein is uromodulin, the most abundant protein in urine with functions that prevent calcification and growth of bacteria. Specific proteins are expressed in the different compartments of the kidney with podocin and nephrin expressed in glomeruli, Solute carrier family protein SLC22A8 expressed in proximal tubules, calbindin expressed in distal tubules and aquaporin 2 expressed in the collecting duct cells.[28]

Development

The mammalian kidney develops from intermediate mesoderm. Kidney development, also called nephrogenesis, proceeds through a series of three successive developmental phases: the pronephros, mesonephros, and metanephros. The metanephros are primordia of the permanent kidney.[29]

Function

The kidneys excrete a variety of waste products produced by metabolism into the urine. The microscopic structural and functional unit of the kidney is the nephron. It processes the blood supplied to it via filtration, reabsorption, secretion and excretion; the consequence of those processes is the production of urine. These include the nitrogenous wastes urea, from protein catabolism, and uric acid, from nucleic acid metabolism. The ability of mammals and some birds to concentrate wastes into a volume of urine much smaller than the volume of blood from which the wastes were extracted is dependent on an elaborate countercurrent multiplication mechanism. This requires several independent nephron characteristics to operate: a tight hairpin configuration of the tubules, water and ion permeability in the descending limb of the loop, water impermeability in the ascending loop, and active ion transport out of most of the ascending limb. In addition, passive countercurrent exchange by the vessels carrying the blood supply to the nephron is essential for enabling this function.

The kidney participates in whole-body homeostasis, regulating acid–base balance, electrolyte concentrations, extracellular fluid volume, and blood pressure. The kidney accomplishes these homeostatic functions both independently and in concert with other organs, particularly those of the endocrine system. Various endocrine hormones coordinate these endocrine functions; these include renin, angiotensin II, aldosterone, antidiuretic hormone, and atrial natriuretic peptide, among others.

Formation of urine

Filtration

Filtration, which takes place at the renal corpuscle, is the process by which cells and large proteins are retained while materials of smaller molecular weights are[30] filtered from the blood to make an ultrafiltrate that eventually becomes urine. The adult human kidney generates approximately 180 liters of filtrate a day, most of which is reabsorbed.[31] The normal range for a twenty four hour urine volume collection is 800 to 2,000 milliliters per day.[32] The process is also known as hydrostatic filtration due to the hydrostatic pressure exerted on the capillary walls.

Reabsorption

Reabsorption is the transport of molecules from this ultrafiltrate and into the peritubular capillary network that surrounds the nephron tubules.[33] It is accomplished via selective receptors on the luminal cell membrane. Water is 55% reabsorbed in the proximal tubule. Glucose at normal plasma levels is completely reabsorbed in the proximal tubule. The mechanism for this is the Na+/glucose cotransporter. A plasma level of 350 mg/dL will fully saturate the transporters and glucose will be lost in the urine. A plasma glucose level of approximately 160 is sufficient to allow glucosuria, which is an important clinical clue to diabetes mellitus.

Amino acids are reabsorbed by sodium dependent transporters in the proximal tubule. Hartnup disease is a deficiency of the tryptophan amino acid transporter, which results in pellagra.[34]

| Location of Reabsorption | Reabsorbed nutrient | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Early proximal tubule | Glucose (100%), amino acids (100%), bicarbonate (90%), Na+ (65%), Cl− (65%), phosphate (65%) and H2O (65%) | |

| Thin descending loop of Henle | H2O |

|

| Thick ascending loop of Henle | Na+ (10–20%), K+, Cl−; indirectly induces para cellular reabsorption of Mg2+, Ca2+ |

|

| Early distal convoluted tubule | Na+, Cl− |

|

| Collecting tubules | Na+(3–5%), H2O |

|

| Examples of substances that are reabsorbed in the kidneys, and the hormones that influence those processes.[34] | ||

Secretion

Secretion is the reverse of reabsorption: molecules are transported from the peritubular capillary through the interstitial fluid, then through the renal tubular cell and into the ultrafiltrate.

Excretion

The last step in the processing of the ultrafiltrate is excretion: the ultrafiltrate passes out of the nephron and travels through a tube called the collecting duct, which is part of the collecting duct system, and then to the ureters where it is renamed urine. In addition to transporting the ultrafiltrate, the collecting duct also takes part in reabsorption.

Hormone secretion

The kidneys secrete a variety of hormones, including erythropoietin, calcitriol, and renin. Erythropoietin is released in response to hypoxia (low levels of oxygen at tissue level) in the renal circulation. It stimulates erythropoiesis (production of red blood cells) in the bone marrow. Calcitriol, the activated form of vitamin D, promotes intestinal absorption of calcium and the renal reabsorption of phosphate. Renin is an enzyme which regulates angiotensin and aldosterone levels.

Blood pressure regulation

Although the kidney cannot directly sense blood, long-term regulation of blood pressure predominantly depends upon the kidney. This primarily occurs through maintenance of the extracellular fluid compartment, the size of which depends on the plasma sodium concentration. Renin is the first in a series of important chemical messengers that make up the renin–angiotensin system. Changes in renin ultimately alter the output of this system, principally the hormones angiotensin II and aldosterone. Each hormone acts via multiple mechanisms, but both increase the kidney's absorption of sodium chloride, thereby expanding the extracellular fluid compartment and raising blood pressure. When renin levels are elevated, the concentrations of angiotensin II and aldosterone increase, leading to increased sodium chloride reabsorption, expansion of the extracellular fluid compartment, and an increase in blood pressure. Conversely, when renin levels are low, angiotensin II and aldosterone levels decrease, contracting the extracellular fluid compartment, and decreasing blood pressure.

Acid–base balance

The two organ systems that help regulate the body's acid–base balance are the kidneys and lungs. Acid–base homeostasis is the maintenance of pH around a value of 7.4. The lungs are the part of respiratory system which helps to maintain acid–base homeostasis by regulating carbon dioxide (CO2) concentration in the blood. The respiratory system is the first line of defense when the body experiences and acid–base problem. It attempts to return the body pH to a value of 7.4 by controlling the respiratory rate. When the body is experiencing acidic conditions, it will increase the respiratory rate which in turn drives off CO2 and decreases the H+ concentration, therefore increasing the pH. In basic conditions, the respiratory rate will slow down so that the body holds onto more CO2 and increases the H+ concentration and decreases the pH.[citation needed]

The kidneys have two cells that help to maintain acid-base homeostasis: intercalated A and B cells. The intercalated A cells are stimulated when the body is experiencing acidic conditions. Under acidic conditions, the high concentration of CO2 in the blood creates a gradient for CO2 to move into the cell and push the reaction HCO3 + H ↔ H2CO3 ↔ CO2 + H2O to the left. On the luminal side of the cell there is a H+ pump and a H/K exchanger. These pumps move H+ against their gradient and therefore require ATP. These cells will remove H+ from the blood and move it to the filtrate which helps to increase the pH of the blood. On the basal side of the cell there is a HCO3/Cl exchanger and a Cl/K co-transporter (facilitated diffusion). When the reaction is pushed to the left it also increases the HCO3 concentration in the cell and HCO3 is then able to move out into the blood which additionally raises the pH. The intercalated B cell responds very similarly, however, the membrane proteins are flipped from the intercalated A cells: the proton pumps are on the basal side and the HCO3/Cl exchanger and K/Cl co-transporter are on the luminal side. They function the same, but now release protons into the blood to decrease the pH.[citation needed]

Regulation of osmolality

The kidneys help maintain the water and salt level of the body. Any significant rise in plasma osmolality is detected by the hypothalamus, which communicates directly with the posterior pituitary gland. An increase in osmolality causes the gland to secrete antidiuretic hormone (ADH), resulting in water reabsorption by the kidney and an increase in urine concentration. The two factors work together to return the plasma osmolality to its normal levels.

Measuring function

Various calculations and methods are used to try to measure kidney function. Renal clearance is the volume of plasma from which the substance is completely cleared from the blood per unit time. The filtration fraction is the amount of plasma that is actually filtered through the kidney. This can be defined using the equation. The kidney is a very complex organ and mathematical modelling has been used to better understand kidney function at several scales, including fluid uptake and secretion.[35][36]

Clinical significance

Nephrology is the subspeciality under Internal Medicine that deals with kidney function and disease states related to renal malfunction and their management including dialysis and kidney transplantation. Urology is the specialty under Surgery that deals with kidney structure abnormalities such as kidney cancer and cysts and problems with urinary tract. Nephrologists are internists, and urologists are surgeons, whereas both are often called "kidney doctors". There are overlapping areas that both nephrologists and urologists can provide care such as kidney stones and kidney related infections.

There are many causes of kidney disease. Some causes are acquired over the course of life, such as diabetic nephropathy whereas others are congenital, such as polycystic kidney disease.

Medical terms related to the kidneys commonly use terms such as renal and the prefix nephro-. The adjective renal, meaning related to the kidney, is from the Latin rēnēs, meaning kidneys; the prefix nephro- is from the Ancient Greek word for kidney, nephros (νεφρός).[37] For example, surgical removal of the kidney is a nephrectomy, while a reduction in kidney function is called renal dysfunction.

Acquired Disease

- Diabetic nephropathy

- Glomerulonephritis

- Hydronephrosis is the enlargement of one or both of the kidneys caused by obstruction of the flow of urine.

- Interstitial nephritis

- Kidney stones (nephrolithiasis) are a relatively common and particularly painful disorder. A chronic condition can result in scars to the kidneys. The removal of kidney stones involves ultrasound treatment to break up the stones into smaller pieces, which are then passed through the urinary tract. One common symptom of kidney stones is a sharp to disabling pain in the middle and sides of the lower back or groin.

- Kidney tumour

- Lupus nephritis

- Minimal change disease

- In nephrotic syndrome, the glomerulus has been damaged so that a large amount of protein in the blood enters the urine. Other frequent features of the nephrotic syndrome include swelling, low serum albumin, and high cholesterol.

- Pyelonephritis is infection of the kidneys and is frequently caused by complication of a urinary tract infection.

- Kidney failure

- Renal artery stenosis

- Renovascular hypertension

Kidney injury and failure

Generally, humans can live normally with just one kidney, as one has more functioning renal tissue than is needed to survive. Only when the amount of functioning kidney tissue is greatly diminished does one develop chronic kidney disease. Renal replacement therapy, in the form of dialysis or kidney transplantation, is indicated when the glomerular filtration rate has fallen very low or if the renal dysfunction leads to severe symptoms.[38]

Dialysis

Dialysis is a treatment that substitutes for the function of normal kidneys. Dialysis may be instituted when approximately 85%–90% of kidney function is lost, as indicated by a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of less than 15. Dialysis removes metabolic waste products as well as excess water and sodium (thereby contributing to regulating blood pressure); and maintains many chemical levels within the body. Life expectancy is 5–10 years for those on dialysis; some live up to 30 years. Dialysis can occur via the blood (through a catheter or arteriovenous fistula), or through the peritoneum (peritoneal dialysis) Dialysis is typically administered three times a week for several hours at free-standing dialysis centers, allowing recipients to lead an otherwise essentially normal life.[39]

Congenital disease

- Congenital hydronephrosis

- Congenital obstruction of urinary tract

- Duplex kidneys, or double kidneys, occur in approximately 1% of the population. This occurrence normally causes no complications, but can occasionally cause urinary tract infections.[40][41]

- Duplicated ureter occurs in approximately one in 100 live births

- Horseshoe kidney occurs in approximately one in 400 live births

- Nephroblastoma (Syndromic Wilm's tumour)

- Nutcracker syndrome

- Polycystic kidney disease

- Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease affects patients later in life. Approximately one in 1000 people will develop this condition

- Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease is far less common, but more severe, than the dominant condition. It is apparent in utero or at birth.

- Renal agenesis. Failure of one kidney to form occurs in approximately one in 750 live births. Failure of both kidneys to form used to be fatal; however, medical advances such as amnioinfusion therapy during pregnancy and peritoneal dialysis have made it possible to stay alive until a transplant can occur.

- Renal dysplasia

- Unilateral small kidney

- Multicystic dysplastic kidney occurs in approximately one in every 2400 live births

- Ureteropelvic Junction Obstruction or UPJO; although most cases are congenital, some are acquired.[42]

Diagnosis

Many renal diseases are diagnosed on the basis of a detailed medical history, and physical examination.[43] The medical history takes into account present and past symptoms, especially those of kidney disease; recent infections; exposure to substances toxic to the kidney; and family history of kidney disease.

Kidney function is tested by using blood tests and urine tests. The most common blood tests are creatinine, urea and electrolytes. Urine tests such as urinalysis can evaluate for pH, protein, glucose, and the presence of blood. Microscopic analysis can also identify the presence of urinary casts and crystals.[44] The glomerular filtration rate (GFR) can be directly measured ("measured GFR", or mGFR) but this rarely done in everyday practice. Instead, special equations are used to calculate GFR ("estimated GFR", or eGFR).[45][44]

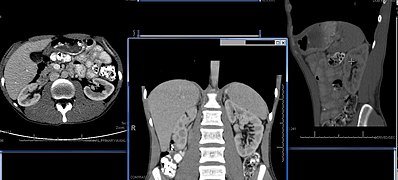

Imaging

Renal ultrasonography is essential in the diagnosis and management of kidney-related diseases.[46] Other modalities, such as CT and MRI, should always be considered as supplementary imaging modalities in the assessment of renal disease.[46]

Biopsy

The role of the renal biopsy is to diagnose renal disease in which the etiology is not clear based upon noninvasive means (clinical history, past medical history, medication history, physical exam, laboratory studies, imaging studies). In general, a renal pathologist will perform a detailed morphological evaluation and integrate the morphologic findings with the clinical history and laboratory data, ultimately arriving at a pathological diagnosis. A renal pathologist is a physician who has undergone general training in anatomic pathology and additional specially training in the interpretation of renal biopsy specimens.

Ideally, multiple core sections are obtained and evaluated for adequacy (presence of glomeruli) intraoperatively. A pathologist/pathology assistant divides the specimen(s) for submission for light microscopy, immunofluorescence microscopy and electron microscopy.

The pathologist will examine the specimen using light microscopy with multiple staining techniques (hematoxylin and eosin/H&E, PAS, trichrome, silver stain) on multiple level sections. Multiple immunofluorescence stains are performed to evaluate for antibody, protein and complement deposition. Finally, ultra-structural examination is performed with electron microscopy and may reveal the presence of electron-dense deposits or other characteristic abnormalities that may suggest an etiology for the patient's renal disease.

Other animals

In the majority of vertebrates, the mesonephros persists into the adult, albeit usually fused with the more advanced metanephros; only in amniotes is the mesonephros restricted to the embryo. The kidneys of fish and amphibians are typically narrow, elongated organs, occupying a significant portion of the trunk. The collecting ducts from each cluster of nephrons usually drain into an archinephric duct, which is homologous with the vas deferens of amniotes. However, the situation is not always so simple; in cartilaginous fish and some amphibians, there is also a shorter duct, similar to the amniote ureter, which drains the posterior (metanephric) parts of the kidney, and joins with the archinephric duct at the bladder or cloaca. Indeed, in many cartilaginous fish, the anterior portion of the kidney may degenerate or cease to function altogether in the adult.[47]

In the most primitive vertebrates, the hagfish and lampreys, the kidney is unusually simple: it consists of a row of nephrons, each emptying directly into the archinephric duct. Invertebrates may possess excretory organs that are sometimes referred to as "kidneys", but, even in Amphioxus, these are never homologous with the kidneys of vertebrates, and are more accurately referred to by other names, such as nephridia.[47] In amphibians, kidneys and the urinary bladder harbour specialized parasites, monogeneans of the family Polystomatidae.[48]

The kidneys of reptiles consist of a number of lobules arranged in a broadly linear pattern. Each lobule contains a single branch of the ureter in its centre, into which the collecting ducts empty. Reptiles have relatively few nephrons compared with other amniotes of a similar size, possibly because of their lower metabolic rate.[47]

Birds have relatively large, elongated kidneys, each of which is divided into three or more distinct lobes. The lobes consists of several small, irregularly arranged, lobules, each centred on a branch of the ureter. Birds have small glomeruli, but about twice as many nephrons as similarly sized mammals.[47]

The human kidney is fairly typical of that of mammals. Distinctive features of the mammalian kidney, in comparison with that of other vertebrates, include the presence of the renal pelvis and renal pyramids and a clearly distinguishable cortex and medulla. The latter feature is due to the presence of elongated loops of Henle; these are much shorter in birds, and not truly present in other vertebrates (although the nephron often has a short intermediate segment between the convoluted tubules). It is only in mammals that the kidney takes on its classical "kidney" shape, although there are some exceptions, such as the multilobed reniculate kidneys of pinnipeds and cetaceans.[47]

Evolutionary adaptation

Kidneys of various animals show evidence of evolutionary adaptation and have long been studied in ecophysiology and comparative physiology. Kidney morphology, often indexed as the relative medullary thickness, is associated with habitat aridity among species of mammals[49] and diet (e.g., carnivores have only long loops of Henle).[36]

Society and culture

Significance

Egyptian

In ancient Egypt, the kidneys, like the heart, were left inside the mummified bodies, unlike other organs which were removed. Comparing this to the biblical statements, and to drawings of human body with the heart and two kidneys portraying a set of scales for weighing justice, it seems that the Egyptian beliefs had also connected the kidneys with judgement and perhaps with moral decisions.[50]

Hebrew

According to studies in modern and ancient Hebrew, various body organs in humans and animals served also an emotional or logical role, today mostly attributed to the brain and the endocrine system. The kidney is mentioned in several biblical verses in conjunction with the heart, much as the bowels were understood to be the "seat" of emotion – grief, joy and pain.[51] Similarly, the Talmud (Berakhoth 61.a) states that one of the two kidneys counsels what is good, and the other evil.

In the sacrifices offered at the biblical Tabernacle and later on at the temple in Jerusalem, the priests were instructed[52] to remove the kidneys and the adrenal gland covering the kidneys of the sheep, goat and cattle offerings, and to burn them on the altar, as the holy part of the "offering for God" never to be eaten.[53]

India: Ayurvedic system

In ancient India, according to the Ayurvedic medical systems, the kidneys were considered the beginning of the excursion channels system, the 'head' of the Mutra Srotas, receiving from all other systems, and therefore important in determining a person's health balance and temperament by the balance and mixture of the three 'Dosha's – the three health elements: Vatha (or Vata) – air, Pitta – bile, and Kapha – mucus. The temperament and health of a person can then be seen in the resulting color of the urine.[54]

Modern Ayurveda practitioners, a practice which is characterized as pseudoscience,[55] have attempted to revive these methods in medical procedures as part of Ayurveda Urine therapy.[56] These procedures have been called "nonsensical" by skeptics.[57]

Medieval Christianity

The Latin term renes is related to the English word "reins", a synonym for the kidneys in Shakespearean English (e.g. Merry Wives of Windsor 3.5), which was also the time when the King James Version of the Bible was translated. Kidneys were once popularly regarded as the seat of the conscience and reflection,[58][59] and a number of verses in the Bible (e.g. Ps. 7:9, Rev. 2:23) state that God searches out and inspects the kidneys, or "reins", of humans, together with the heart.[60]

History

Kidney stones have been identified and recorded about as long as written historical records exist.[61] The urinary tract including the ureters, as well as their function to drain urine from the kidneys, has been described by Galen in the second century AD.[62]

The first to examine the ureter through an internal approach, called ureteroscopy, rather than surgery was Hampton Young in 1929.[61] This was improved on by VF Marshall who is the first published use of a flexible endoscope based on fiber optics, which occurred in 1964.[61] The insertion of a drainage tube into the renal pelvis, bypassing the uterers and urinary tract, called nephrostomy, was first described in 1941. Such an approach differed greatly from the open surgical approaches within the urinary system employed during the preceding two millennia.[61]

Additional images

-

Right kidney

-

Kidney

-

Right kidney

-

Right kidney

-

Left kidney

-

Kidneys

-

Left kidney

See also

- Artificial kidney

- Holonephros

- Nephromegaly

- Organ donation

- Organ harvesting

- Pelvic kidney

- World Kidney Day

- List of distinct cell types in the adult human body

References

Citations

- ^ "Kidneys: Anatomy, Function, Health & Conditions". Cleveland Clinic. Archived from the original on 2023-06-29. Retrieved 2023-07-13.

- ^ Zhou, Xin J.; Laszik, Zoltan G.; Nadasdy, Tibor; D'Agati, Vivette D. (2017-03-02). Silva's Diagnostic Renal Pathology. Cambridge University Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-316-61398-6. Archived from the original on 2023-04-04. Retrieved 2023-08-16.

- ^ Haschek, Wanda M.; Rousseaux, Colin G.; Wallig, Matthew A.; Bolon, Brad; Ochoa, Ricardo (2013-05-01). Haschek and Rousseaux's Handbook of Toxicologic Pathology. Academic Press. p. 1678. ISBN 978-0-12-415765-1.

- ^ Lote CJ (2012). Principles of Renal Physiology, 5th edition. Springer. p. 21.

- ^ Mescher AL (2016). Junqueira's Basic Histology, 14th edition. Lange. p. 393.

- ^ Lv JC, Zhang LX (2019). "Prevalence and Disease Burden of Chronic Kidney Disease". Renal Fibrosis: Mechanisms and Therapies. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Vol. 1165. pp. 3–15. doi:10.1007/978-981-13-8871-2_1. ISBN 978-981-13-8871-2. PMID 31399958. S2CID 199519437.

- ^ Cotran RS, Kumar V, Fausto N, Robbins SL, Abbas AK (2005). Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders. ISBN 978-0-7216-0187-8.

- ^ Kalantar-Zadeh K, McCullough PA, Agarwal SK, Beddhu S, Boaz M, Bruchfeld A, et al. (June 2021). "Nomenclature in nephrology: preserving 'renal' and 'nephro' in the glossary of kidney health and disease". Journal of Nephrology. 34 (3): 639–648. doi:10.1007/s40620-021-01011-3. PMC 8192439. PMID 33713333.

- ^ "HowStuffWorks How Your Kidney Works". 2001-01-10. Archived from the original on 2012-11-05. Retrieved 2012-08-09.

- ^ "Kidneys Location Stock Illustration". Archived from the original on 2013-09-27.

- ^ "Kidney". BioPortfolio Ltd. Archived from the original on 10 February 2008.

- ^ Glodny B, Unterholzner V, Taferner B, Hofmann KJ, Rehder P, Strasak A, Petersen J (December 2009). "Normal kidney size and its influencing factors - a 64-slice MDCT study of 1.040 asymptomatic patients". BMC Urology. 9 (1): 19. doi:10.1186/1471-2490-9-19. PMC 2813848. PMID 20030823.

- ^ Dragomir A, Hjortberg M, Romans GM. Bålens ytanatomy [Superficial anatomy of the trunk]. Section for human anatomy at the Department of Medical Biology, Uppsala University, Sweden (Report) (in Swedish).

- ^ "Renal system". Britannica. Archived from the original on 2022-05-31. Retrieved 2022-05-22.

- ^ Molina DK, DiMaio VJ (December 2012). "Normal organ weights in men: part II – the brain, lungs, liver, spleen, and kidneys". The American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology. 33 (4): 368–372. doi:10.1097/PAF.0b013e31823d29ad. PMID 22182984. S2CID 32174574.

- ^ Molina DK, DiMaio VJ (September 2015). "Normal Organ Weights in Women: Part II-The Brain, Lungs, Liver, Spleen, and Kidneys". The American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology. 36 (3): 182–187. doi:10.1097/PAF.0000000000000175. PMID 26108038. S2CID 25319215.

- ^ Emamian SA, Nielsen MB, Pedersen JF, Ytte L (January 1993). "Kidney dimensions at sonography: correlation with age, sex, and habitus in 665 adult volunteers". AJR. American Journal of Roentgenology. 160 (1): 83–86. doi:10.2214/ajr.160.1.8416654. PMID 8416654.

- ^ a b Boron WF (2004). Medical Physiology: A Cellular And Molecular Approach. Elsevier/Saunders. ISBN 978-1-4160-2328-9.

- ^ Clapp WL (2009). "Renal Anatomy". In Zhou XJ, Laszik Z, Nadasdy T, D'Agati VD, Silva FG (eds.). Silva's Diagnostic Renal Pathology. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-87702-2.

- ^ Prothero, John William, ed. (2015), "Urinary system", The Design of Mammals: A Scaling Approach, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 195–203, doi:10.1017/CBO9781316275108.016, ISBN 978-1-107-11047-2, archived from the original on 2018-06-17, retrieved 2022-06-25

- ^ Martini, Frederic; Tallitsch, Robert B.; Nath, Judi L. (2017). Human Anatomy (9th ed.). Pearson. p. 689. ISBN 9780134320762.

- ^ a b c d e Bard J, Vize PD, Woolf AS (2003). The kidney: from normal development to congenital disease. Boston: Academic Press. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-12-722441-1. Archived from the original on 2023-08-17. Retrieved 2020-10-19.

- ^ Cheng, Xiaofeng; Zhang, Yongsheng; Chen, Ruixi; Qian, Shenghui; Lv, Haijun; Liu, Xiuli; Zeng, Shaoqun (December 2022). "Anatomical Evidence for Parasympathetic Innervation of the Renal Vasculature and Pelvis". Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 33 (12): 2194–2210. doi:10.1681/ASN.2021111518. ISSN 1046-6673. PMC 9731635. PMID 36253054.

- ^ Schrier RW, Berl T (October 1972). "Mechanism of the antidiuretic effect associated with interruption of parasympathetic pathways". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 51 (10): 2613–2620. doi:10.1172/JCI107079. PMC 332960. PMID 5056657.

- ^ M. Cecilia Cirio; Eric D. de Groh; Mark P. de Caestecker; Alan J. Davidson; Neil A. Hukriede (April 2014). "Kidney regeneration: common themes from the embryo to the adult". Pediatric Nephrology. 29 (4): 553–64. doi:10.1007/S00467-013-2597-2. ISSN 0931-041X. PMC 3944192. PMID 24005792. Wikidata Q27013996.

- ^ "The human proteome in kidney – The Human Protein Atlas". www.proteinatlas.org. Archived from the original on 2017-09-22. Retrieved 2017-09-22.

- ^ Uhlén M, Fagerberg L, Hallström BM, Lindskog C, Oksvold P, Mardinoglu A, et al. (January 2015). "Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome". Science. 347 (6220): 1260419. doi:10.1126/science.1260419. PMID 25613900. S2CID 802377.

- ^ Habuka M, Fagerberg L, Hallström BM, Kampf C, Edlund K, Sivertsson Å, et al. (2014-12-31). "The kidney transcriptome and proteome defined by transcriptomics and antibody-based profiling". PLOS ONE. 9 (12): e116125. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9k6125H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0116125. PMC 4281243. PMID 25551756.

- ^ Carlson BM (2004). Human Embryology and Developmental Biology (3rd ed.). Saint Louis: Mosby. ISBN 978-0-323-03649-8.

- ^ Hall JE (2016). Guyton and Hall textbook of medical physiology (13th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1129. ISBN 978-0-323-38930-3.

- ^ Alpern, Robert J.; Caplan, Michael; Moe, Orson W. (2012-12-31). Seldin and Giebisch's The Kidney: Physiology and Pathophysiology. Academic Press. p. 1405. ISBN 978-0-12-381463-0. Archived from the original on 2023-07-22. Retrieved 2022-07-28.

- ^ "Urine 24-hour volume". mountsinai. Archived from the original on 21 November 2022. Retrieved 21 November 2022.

- ^ Kumaran GK, Hanukoglu I (2024). "Mapping the cytoskeletal architecture of renal tubules and surrounding peritubular capillaries in the kidney". Cytoskeleton (Hoboken). 81 (4–5): 227–237. doi:10.1002/cm.21809. PMID 37937511.

- ^ a b Le, Tao. First Aid for the USMLE Step 1 2013. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical, 2013. Print.

- ^ Weinstein AM (1994). "Mathematical models of tubular transport". Annual Review of Physiology. 56: 691–709. doi:10.1146/annurev.physiol.56.1.691. PMID 8010757.

- ^ a b Thomas SR (2005). "Modelling and simulation of the kidney". Journal of Biological Physics and Chemistry. 5 (2/3): 70–83. doi:10.4024/230503.jbpc.05.02.

- ^ Maton A, Hopkins J, McLaughlin CW, Johnson S, Warner MQ, LaHart D, Wright JD (1993). Human Biology and Health. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, USA: Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-981176-0.

- ^ Kalantar-Zadeh K, Jafar TH, Nitsch D, Neuen BL, Perkovic V (August 2021). "Chronic kidney disease" (PDF). Lancet. 398 (10302): 786–802. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00519-5. PMID 34175022. S2CID 235631509. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-05-17. Retrieved 2022-05-22.

- ^ "Dialysis". National Kidney Foundation. 2015-12-24. Archived from the original on 2017-09-26. Retrieved 8 November 2017.

- ^ Sample I (2008-02-19). "How many people have four kidneys?". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 2016-08-17. Retrieved 2016-12-19.

- ^ "Kidneys Fail, Girl Survives with Spare Parts". Abcnews.go.com. 2010-05-18. Archived from the original on 2010-05-21. Retrieved 2011-01-03.

- ^ Novick AC, Gill IS, Klein EA, Rackley R, Ross JH, Jones JS (2006). "Ureteropelvic Junction Obstruction". Operative Urology at the Cleveland Clinic. Vol. 8. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press. pp. S102–S108. doi:10.1007/978-1-59745-016-4_16. ISBN 978-1-58829-081-6. PMC 4869439.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Gaitonde DY (15 December 2017). "Chronic Kidney Disease: Detection and Evaluation". Am Fam Physician. 12 (96): 776–783. Archived from the original on 26 February 2021. Retrieved 1 March 2021.

- ^ a b Post TW, Rose BD (December 2012). Curhan GC, Sheridan AM (eds.). "Diagnostic Approach to the Patient With Acute Kidney Injury (Acute Kidney Failure) or Chronic Kidney Disease". www.uptodate.com. Archived from the original on 2015-11-10. Retrieved 2016-12-19.

- ^ "KDIGO 2012 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease". Kidney Int Suppl. 3: 1–150. 2013. Archived from the original on 2019-05-01. Retrieved 2021-01-25.

- ^ a b Content initially copied from: Hansen KL, Nielsen MB, Ewertsen C (December 2015). "Ultrasonography of the Kidney: A Pictorial Review". Diagnostics. 6 (1): 2. doi:10.3390/diagnostics6010002. PMC 4808817. PMID 26838799. (CC-BY 4.0) Archived 2017-10-16 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e Romer AS, Parsons TS (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 367–376. ISBN 978-0-03-910284-5.

- ^ Theunissen M, Tiedt L, Du Preez LH (2014). "The morphology and attachment of Protopolystoma xenopodis (Monogenea: Polystomatidae) infecting the African clawed frog Xenopus laevis". Parasite. 21: 20. doi:10.1051/parasite/2014020. PMC 4018937. PMID 24823278.

- ^ al-Kahtani MA, Zuleta C, Caviedes-Vidal E, Garland T (2004). "Kidney mass and relative medullary thickness of rodents in relation to habitat, body size, and phylogeny" (PDF). Physiological and Biochemical Zoology. 77 (3): 346–365. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.407.8690. doi:10.1086/420941. PMID 15286910. S2CID 12420368. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-06-17. Retrieved 2009-03-28.

- ^ Salem ME, Eknoyan G (1999). "The kidney in ancient Egyptian medicine: where does it stand?". American Journal of Nephrology. 19 (2): 140–147. doi:10.1159/000013440. PMID 10213808. S2CID 35305403.

- ^ "Body Part Metaphors in Biblical Hebrew by David Steinberg". March 22, 2003. Archived from the original on March 22, 2003. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- ^ Leviticus 3: 4, 10 and 15

- ^ ie Deut 3:4,9,10,15... or the Babylonian Talmud, Bechorot (39a) Ch6:Tr2...

- ^ "What is Vata Dosha? Tips and diet for balancing vata | CA College of Ayurveda". www.ayurvedacollege.com. 7 April 2010. Archived from the original on 9 November 2019. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- ^ List of topics characterized as pseudoscience, according to the American Medical Association's Report 12 of the Council of Scientific Affairs (A-97) and claims by skeptics Archived 2016-08-10 at the Wayback Machine ('The Skeptics Dictionary' website)

- ^ Sangu PK, Kumar VM, Shekhar MS, Chagam MK, Goli PP, Tirupati PK (January 2011). "A study on Tailabindu pariksha – An ancient Ayurvedic method of urine examination as a diagnostic and prognostic tool". AYU. 32 (1): 76–81. doi:10.4103/0974-8520.85735. PMC 3215423. PMID 22131762.

- ^ Barrett S. "A Few Thoughts on Ayurvedic Mumbo-Jumbo". Archived from the original on 2020-09-29. Retrieved 2022-05-22. M.D, head of the National Council Against Health Fraud NGO and owner of the QuackWatch website.

- ^ Ramsey P, Jonsen AR, May WF (2002). The Patient as Person: Explorations in Medical Ethics (Second ed.). New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-300-09396-4.

- ^ Eknoyan G, Marketos SG, De Santo NG, eds. (January 1997). History of Nephrology 2. Karger Medical and Scientific Publishers. p. 235. ISBN 978-3-8055-6499-1. International Association for the History of Nephrology Congress, Reprint of American Journal of Nephrology; v. 14, no. 4–6, 1994.

- ^ intertextual.bible/text/revelation-2.23-berakhot-119.29, archived from the original on 2022-12-15, retrieved 2022-12-15

- ^ a b c d Tefekli A, Cezayirli F (November 2013). "The history of urinary stones: in parallel with civilization". TheScientificWorldJournal. 2013: 423964. doi:10.1155/2013/423964. PMC 3856162. PMID 24348156.

- ^ Nahon I, Waddington G, Dorey G, Adams R (2011). "The history of urologic surgery: from reeds to robotics". Urologic Nursing. 31 (3): 173–180. doi:10.7257/1053-816X.2011.31.3.173. PMID 21805756.

General and cited references

- Barrett KE, Barman SM, Yuan JX, Brooks H (2019). Ganong's review of medical physiology (26th ed.). New York. ISBN 9781260122404. OCLC 1076268769.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)