Voeren

Voeren

Fourons (French) | |

|---|---|

Sint-Martens-Voeren | |

| Coordinates: 50°45′N 05°47′E / 50.750°N 5.783°E | |

| Country | |

| Community | Flemish Community |

| Region | Flemish Region |

| Province | Limburg |

| Arrondissement | Tongeren |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Joris Gaens (Voerbelangen, N-VA) |

| • Governing party/ies | Voerbelangen |

| Area | |

• Total | 50.61 km2 (19.54 sq mi) |

| Population (2018-01-01)[1] | |

• Total | 4,160 |

| • Density | 82/km2 (210/sq mi) |

| Postal codes | 3790, 3791, 3792, 3793, 3798 |

| NIS code | 73109 |

| Area codes | 04 |

| Website | www.voeren.be |

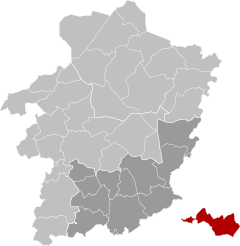

Voeren (Dutch pronunciation: [ˈvuːrə(n)] ; French: Fourons [fuʁɔ̃]) is a Flemish Dutch-speaking municipality with facilities for the French-speaking minority, located in the Belgian province of Limburg. Bordering the Netherlands to the north and the Wallonia region's Liège Province (Dutch: Luik) to the south, it is geographically detached from the rest of Flanders, making Voeren an exclave of Flanders. Voeren's name is derived from that of a small right-bank tributary of the Meuse, the Voer, which flows through the municipality.

The current municipality of Voeren was established by the municipal reform of 1977. On 1 January 2008, Voeren had a total population of 4,207. Its total area is 50.63 km2 (19.55 sq mi), giving a population density of 83 inhabitants per square kilometre (210/sq mi). About 25% of the population is made up of foreign nationals, most of whom have Dutch nationality.

Villages

[edit]The municipality consists of the six villages of 's-Gravenvoeren (French: Fouron-le-Comte), Sint-Pieters-Voeren (French: Fouron-Saint-Pierre), Sint-Martens-Voeren (French: Fouron-Saint-Martin), Moelingen (French: Mouland), Teuven and Remersdaal (French: Rémersdael, Walloon: Rèbiévå). 's-Gravenvoeren is the most important and most populous village of the municipality. Locally, the three villages are named Sint-Marten (French: Saint-Martin), Sint-Pieter (French: Saint-Pierre), and Voeren (French: Fouron) for 's-Gravenvoeren.

History

[edit]Since the 11th century, two-thirds of the territory of the present municipality of Voeren was in the county of Dalhem, which was a possession of the dukes of Brabant, and the remaining one-third in the Duchy of Limburg, which also belonged to Brabant after 1288. Both of these duchies were part of the Holy Roman Empire but they developed a relatively independent regime ruled by powerful dynasties. They successively became part of the Burgundian Netherlands, the Habsburg Netherlands, and after the Dutch Revolt, part of the Spanish, later Austrian controlled, Southern Netherlands.

During the French occupation (1794–1815), the old boundaries of the "ancien regime" were rejected and the French "département" of Ourthe was created. After the defeat of France and the end of Napoleonic wars, this became the modern Belgium's Liège Province until 1963 when the Voer Region was detached from Liège, and became part of the province of Limburg, within Flanders.

Linguistic and political issues

[edit]Most native people in Voeren speak a variant of Limburgish, a regional language related to Dutch (in the Netherlands referred to as a separate language; in Flanders treated as a Dutch dialect), and German. The same Germanic dialect is also spoken in the neighbouring Walloon municipalities of Blieberg, Welkenraedt and Baelen and has been recognised by the French Community of Belgium as a regional language since 1990.[2]

Voeren is economically dependent on the surrounding provinces of Liège and Dutch Limburg and standard Dutch and French are also generally spoken.

Until the beginning of the 20th century, language use in the area was mixed. People spoke the local dialect in daily life. The government institutions used French, while church and school used German or Dutch. However, some influential inhabitants, such as the local priest, Hendrik Veltmans, argued that Voeren was culturally Flemish and actively tried to bring Voeren into Flanders.

In 1932, with the introduction of new language laws, the linguistic alignment of Voeren was determined (as for all other towns along the language border in Belgium) on the basis of the results of the census of 1930. According to this census, 81.2% of the population of the six villages that now make up Voeren spoke Dutch, and 18.8% declared that they spoke French. Administrative changes were made as a result. The results of the next census, held in 1947, were only made public in 1954 and gave a totally different outcome, with only 42.9% stating that they spoke Dutch and 57.1% French. According to the 1932 legislation, this would have meant that the linguistic status of the villages would have changed from Dutch speaking with a French minority to French speaking with a Dutch-speaking minority. At that time, however, due to the rising political controversy between the Dutch- and French-speaking communities in Belgium, a parliamentary committee (the so-called centrum Harmel, named after Pierre Harmel) was established to fix, amongst other things, the language boundary once and for all. This committee proposed, notwithstanding the 1947 results (strongly disputed by the Flemish and recognised by the Belgian parliament as useless for determining the language border since the consultation was found to be rigged by nationalist francophones which is why the 1947 results were published in 1954[3]), that the six villages were Dutch speaking with special regulations for the French-speaking minority to be decided after discussion with the town councils.

In 1962 the work of the committee resulted in a law proposed by the French-speaking Minister of the Interior, Arthur Gilson, whereby Voeren would be officially Dutch speaking with language facilities for the French-speaking community, but would remain part of the French-speaking Liège Province. The proposal included a similar system for Mouscron and Comines-Warneton which would be officially French-speaking with language facilities for the Dutch-speaking community, but would remain part of the Dutch-speaking province of West-Flanders.[4]

After fierce debate in parliament, the proposal of minister Gilson was approved but subject to the amendment that Voeren would become part of the Dutch-speaking province of Limburg and Mouscron and Comines-Warneton become part of the French-speaking Hainaut province.

This amendment was introduced by the Walloon socialist politician and former mayor of Liège, Paul Gruselin, who wanted to transfer the Flemish towns with a Francophone majority Comines-Warneton and Mouscron to the Walloon province of Hainaut and offered to transfer the Voer region to the Dutch-speaking province of Limburg as compensation.[5][6][7][8]

In order to understand this proposal of the Walloon socialists of Liège and Mouscron, one must take into account the fact that almost everyone at the time considered that a Dutch dialect was spoken in the Voer Region and that, consequently, their inhabitants would willingly accept this change. The 75,000 inhabitants of the towns Mouscron and Comines-Warneton brought one extra deputy's seat while the 4,000 inhabitants of the villages of the Voer Region were far from being worth as much.[9]

This switch from Liège to Limburg was received badly by many local people because of the region's dependence on Liège. Francophones in particular campaigned for the region to be returned to the province of Liège. Similarly in Comines-Warneton and Mouscron, the city councils[10] and a large majority of the population wanted to remain part of the Dutch-speaking province of West Flanders[11] or at the very least become a new francophone province together with the city of Tournai, the Tournaisis because they identified as Frenchified Flemings, having shared a history with the other regions of the former County of Flanders and felt culturally closer to French Flanders than to the Hainaut Province.[12]

On 1 January 1977, the six small municipalities were merged into the present-day Voeren municipality. The Francophone and Flemish movements could organize themselves politically more effectively as there was now one, instead of six, municipal council. This resulted in political and linguistic strife between the Francophone Retour à Liège (Return to Liège) party and the Flemish Voerbelangen (Voeren's Best Interests) party. The Retour à Liège faction won a majority in the new council. There were also action committees on both sides and gangs who daubed place-name signs and took part in violent demonstrations. The language struggle in Voeren became a national issue, and people from outside the region became involved.

The linguistic struggle came to a head when José Happart was put forward as mayor in 1983. For one thing, he was alleged to have supported the Francophone gangs in Voeren. However, the main problem was the constitutional question of whether someone who could not speak Dutch could become mayor of a Flemish municipality. Happart was dismissed as mayor for refusing to take a Dutch-language test, but appealed against his dismissal, and the question dragged on for years, ultimately causing the Belgian government Martens VI to fall on 19 October 1987.

In 1988, concessions to the Francophone inhabitants were made. The powers of the provincial government of Limburg were curtailed, and more autonomy was given to the municipality. The government of the Walloon Region was allowed to build facilities for Francophones in Voeren.

In the 1994 municipal elections, the Dutch-speaking party (Voerbelangen) won a seat more than in earlier elections but was still a minority on the council. In 1995, Mayor Happart was forced to leave office. The national court of arbitration (now Belgian Constitutional Court) declared some of the 1988 concessions unconstitutional (e.g. the Walloon building rights).

EU nationals were given suffrage at the municipal level in 1999. This factor was decisive in the 2000 municipal elections, because of the significant number of Dutch citizens living in Voeren (about 20% of the total population): Voerbelangen won a majority of 53% of the votes and 8 out of 15 local council seats. However, the new majority faced budgetary difficulties, since large debts had been incurred by the previous administration. The council had to sell several items of municipal property, such as forests and goods[clarification needed] to stabilise its finances. As from 2003 to 2004 the council is viable again, and new projects are being started to fulfill the promises made during the elections. In the 2006 municipal elections Voerbelangen won again, gaining 61% of the votes and 9 out of 15 council seats. For the first time, Voerbelangen also won the majority of the seats in the council of the OCMW (Public Centre for Social Welfare), the social affairs department of the municipality, for which nationals of other EU countries may not vote. Though the violence of the 1970s and 1980s has subsided, some activists still daub graffiti on place-name signs. In December 2006, the Flemish Government decided to abolish all official French translations in Flemish municipalities and villages, including municipalities with language facilities. Thus the French names of the Voeren municipality and villages will no longer be used on place-name signs, traffic signs and by municipality and other governments in official documents.

Results of the linguistic censuses of 1930 and 1947 per village

[edit]Precise figures on the ethnic composition of Belgium are impossible to obtain, for the language question is so controversial that the Belgian census has not included data on linguistic composition of communes since 1947. [citation needed]

| 1930 | 1947 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dutch speaking | French speaking | Dutch speaking | French speaking | |||||

| Moelingen | 469 | 72.8% | 177 | 27.2% | 182 | 43.7% | 487 | 56.3% |

| 's Gravenvoeren | 922 | 75.0% | 307 | 25.0% | 521 | 43.7% | 672 | 56.3% |

| Sint-Martens-Voeren | 805 | 90.1% | 88 | 9.9% | 480 | 58.0% | 348 | 42.0% |

| Sint-Pieters-Voeren | 249 | 86.8% | 38 | 13.2% | 163 | 49.8% | 164 | 50.2% |

| Teuven | 538 | 90.9% | 54 | 9.1% | 283 | 46.6% | 324 | 53.4% |

| Remersdaal | 316 | 75.6% | 102 | 24.4% | 92 | 23.8% | 294 | 76.2% |

| Total | 3,299 | 81.2% | 766 | 18.8% | 1,721 | 42.9% | 2,289 | 57.1% |

Gallery

[edit]-

Altembrouck castle at 's Gravenvoeren

-

Remersdaal

-

Teuven

-

Moelingen

-

Sint-Pieters-Voeren church

-

Sint-Pieters-Voeren castle

See also

[edit]- Comines-Warneton, a similarly detached part of Wallonia.

- [1], A Klankatlas 2013 commission by sound artists Jonathon Kirk and Thomas Smetryns of a soundscape composition of the Voeren.

References

[edit]- ^ "Wettelijke Bevolking per gemeente op 1 januari 2018". Statbel. Retrieved 9 March 2019.

- ^ "Langues régionales endogènes". www.languesregionales.cfwb.be (in French). 2011-11-09. Retrieved 2020-08-08.

- ^ "Kamer van Volksvertegewoordigers | Chambre des Représentants" (PDF). Parliamentary Documents, Belgian Chamber of Representatives 1961–1962, Nr. 194/7 (in French and Dutch): 5. Dec 21, 1961. Retrieved 2023-04-04.

- ^ "Kamer van Volksvertegewoordigers | Chambre des Représentants" (PDF). Parliamentary Documents, Belgian Chamber of Representatives 1961–1962, Nr. 194/7 (in French and Dutch): 6. Dec 21, 1961. Retrieved 2023-04-04.

- ^ "Belgian Chamber of Representatives • Session of 1 July 1987 - plenum.be". sites.google.com. Retrieved 2020-08-01.

- ^ "Communautaire - Il y a quarante ans, la Belgique se réveillait divisée en deux par un " mur de betteraves " L'unique frontière sans douane La victoire du droit du sol La légende de la trahison socialiste". Le Soir (in French). Retrieved 2020-08-01.

- ^ "Kamer van Volksvertegewoordigers | Chambre des Représentants" (PDF). Parliamentary Documents, Belgian Chamber of Representatives 1961–1962, Nr. 194/7 (in French and Dutch): 25. Dec 21, 1961. Retrieved 2023-04-04.

- ^ "Facilités: Gilson aux côtés des maïeurs rebelles En 1962-63, les Flamands ne parlaient pas de facilités temporaires Les Fourons, c'était pas moi! André Cools l'a reconnu..." Le Soir (in French). Retrieved 2020-08-08.

- ^ "Communautaire - Il y a quarante ans, la Belgique se réveillait divisée en deux par un " mur de betteraves " L'unique frontière sans douane La victoire du droit du sol La légende de la trahison socialiste". Le Soir (in French). Retrieved 2020-08-08.

- ^ "Kamer van Volksvertegewoordigers | Chambre des Représentants" (PDF). Parliamentary Documents, Belgian Chamber of Representatives 1961–1962, Nr. 194/7 (in French and Dutch): 12. Dec 21, 1961. Retrieved 2023-04-04.

- ^ "Kamer van Volksvertegewoordigers | Chambre des Représentants" (PDF). Parliamentary Documents, Belgian Chamber of Representatives 1961–1962, Nr. 194/7 (in French and Dutch): 5. Dec 21, 1961. Retrieved 2023-04-04.

- ^ "Kamer van Volksvertegewoordigers | Chambre des Représentants" (PDF). Parliamentary Documents, Belgian Chamber of Representatives 1961–1962, Nr. 194/7 (in French and Dutch): 23. Dec 21, 1961. Retrieved 2023-04-04.

External links

[edit]- Official website – Dutch and French