Religious socialism

| Part of a series on |

| Socialism |

|---|

|

Religious socialism is a type of socialism based on religious values. Members of several major religions have found that their beliefs about human society fit with socialist principles and ideas. As a result, religious socialist movements have developed within these religions. Those movements include Buddhist socialism, Christian socialism, Islamic socialism, and Jewish socialism. According to the Encyclopedia Britannica Online, socialism is a "social and economic doctrine that calls for public rather than private ownership or control of property and natural resources. According to the socialist view, individuals do not live or work in isolation but live in cooperation with one another. Furthermore, everything that people produce is in some sense a social product, and everyone who contributes to the production of a good is entitled to a share in it. Society as a whole, therefore, should own or at least control property for the benefit of all its members. [...] Early Christian communities also practiced the sharing of goods and labour, a simple form of socialism subsequently followed in certain forms of monasticism. Several monastic orders continue these practices today".[1]

The teachings of Jesus are frequently described as socialist, especially by Christian socialists.[2] Acts 4:35 records that in the early church in Jerusalem, "[n]o one claimed that any of their possessions was their own", although the pattern would later disappear from church history except within monasticism. Christian socialism was one of the founding threads of the British Labour Party and is claimed to begin with the uprising of Wat Tyler and John Ball in the 14th century CE.[3]

Abu Dharr al-Ghifari, a companion of Muhammad, is credited by multiple authors as a principal antecedent of Islamic socialism.[4][5][6][7][8] The Hutterites believed in strict adherence to biblical principles and church discipline, and practised a religious form of communism. In the words of historians Rod Janzen and Max Stanton, the Hutterites "established in their communities a rigorous system of Ordnungen, which were codes of rules and regulations that governed all aspects of life and ensured a unified perspective. As an economic system, Christian communism was attractive to many of the peasants who supported social revolution in sixteenth century central Europe", such as the German Peasants' War, and "Friedrich Engels thus came to view Anabaptists as proto-Communists."[9]

Overview

[edit]Religious socialism was the early form of socialism and pre-Marxist communism. In Christian Europe, communists were believed to have adopted atheism. In Protestant England, communism was too close to the Roman Catholic communion rite; hence socialist was the preferred term.[10] Friedrich Engels argued that in 1848, when The Communist Manifesto was published, socialism was respectable in Europe while communism was not. The Owenites in England and the Fourierists in France were considered respectable socialists, while working-class movements that "proclaimed the necessity of total social change" denoted themselves communists. This branch of socialism produced the communist work of Étienne Cabet in France and Wilhelm Weitling in Germany.[11]

Some view the early Christian Church, as described in the Acts of the Apostles, as an early form of communism and religious socialism. The view is that communism was just Christianity in practice, and Jesus was the first communist.[12] This link was highlighted in one of Karl Marx's early writings, which stated that "[a]s Christ is the intermediary unto whom man unburdens all his divinity, all his religious bonds, so the state is the mediator unto which he transfers all his Godlessness, all his human liberty".[12] Furthermore, Thomas Müntzer led a significant Anabaptist communist movement during the German Peasants' War which Engels analysed in The Peasant War in Germany. The Marxist ethos that aims for unity reflects the Christian universalist teaching that humankind is one and that there is only one god who does not discriminate among people.[13] Pre-Marxist communism was also present in the attempts to establish communistic societies such as those made by the Essenes and the Judean desert sect.[14][15][16]

In the 16th century, English writer Thomas More, venerated in the Catholic Church as Saint Thomas More, portrayed a society based on common property ownership in his treatise Utopia, whose leaders administered it through reason.[17] Several groupings in the English Civil War supported this idea, especially the Diggers, who espoused clear communistic yet agrarian ideals.[18][19][20] Oliver Cromwell and the Grandees' attitude to these groups was, at best, ambivalent and often hostile.[21] Criticism of the idea of private property continued into the Enlightenment era of the 18th century through such thinkers as the profoundly religious Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Raised a Calvinist, Rousseau was influenced by the Jansenist movement within the Roman Catholic Church. The Jansenist movement originated from the most orthodox Roman Catholic bishops who tried to reform the Roman Catholic Church in the 17th century to stop secularization and Protestantism. One of the main Jansenist aims was democratizing to stop the aristocratic corruption at the top of the Church hierarchy.[22] The participants of the Taiping Rebellion, who founded the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom, a syncretic Christian-Shenic theocratic kingdom, are viewed by the Chinese Communist Party as proto-communists.[23]

Buddhist socialism

[edit]Buddhist socialism advocates socialism based on the principles of Buddhism. Both Buddhism and socialism seek to provide an end to suffering by analyzing its conditions and removing its leading causes through praxis. Both also seek to provide a transformation of personal consciousness (respectively, spiritual and political) to bring an end to human alienation and selfishness.[24] People described as Buddhist socialists include Buddhadasa Bhikkhu,[25] B. R. Ambedkar, S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike, Han Yong-un,[26] Girō Senoo,[27] U Nu, Uchiyama Gudō[28] and Norodom Sihanouk.[29][30]

Bhikkhu Buddhadasa coined the phrase "Dhammic socialism".[25] He believed that socialism is a natural state,[31] meaning all things exist together in one system.[31] Han Yong-un felt that equality was one of the main principles of Buddhism.[26] In an interview published in 1931, Yong-un spoke of his desire to explore Buddhist socialism: "I am recently planning to write about Buddhist socialism. Just like there is Christian socialism as a system of ideas in Christianity, there must be also Buddhist socialism in Buddhism."[26]

Tenzin Gyatso, the Fourteenth Dalai Lama of Tibet, stated that "[o]f all the modern economic theories, the economic system of Marxism is founded on moral principles, while capitalism is concerned only with gain and profitability. [...] The failure of the regime in the former Soviet Union was, for me, not the failure of Marxism but the failure of totalitarianism. For this reason I still think of myself as half-Marxist, half-Buddhist".[32]

Christian socialism

[edit]Some individuals and groups, past and present, are both Christian and socialist, such as Frederick Denison Maurice, author of The Kingdom of Christ (1838). Another example is the Christian Socialist Movement, affiliated with the British Labour Party. Distributism is an economic philosophy formulated by such Catholic thinkers as G. K. Chesterton and Hilaire Belloc to apply the principles of social justice articulated by the Roman Catholic Church, especially in Pope Leo XIII's encyclical Rerum novarum.

Various Catholic clerical parties have at times referred to themselves as Christian Social. Two examples are the Christian Social Party of Karl Lueger in Austria before and after World War I and the contemporary Christian Social Union in Bavaria. Nonetheless, these parties have never espoused socialist policies and have always stood on the conservative side of Christian democracy.[33] Hugo Chávez of Venezuela was an advocate of a form of Christian socialism as he claimed that Jesus was a socialist.[citation needed]

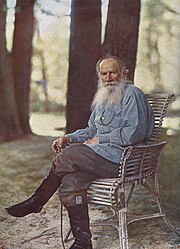

Christian anarchism is a Christian movement in political theology that combines anarchism and Christianity.[34] The foundation of Christian anarchism is a rejection of violence, with Leo Tolstoy's The Kingdom of God Is Within You regarded as a key text.[35][36] Tolstoy sought to separate Russian Orthodox Christianity—which was merged with the state—from what he believed was the true message of Jesus as contained in the Gospels, specifically in the Sermon on the Mount. Tolstoy believed that all governments that wage war, and churches that support those governments, are an affront to the Christian principles of nonviolence and nonresistance. Although Tolstoy never actually used the term Christian anarchism in The Kingdom of God Is Within You, reviews of this book following its publication in 1894 appear to have coined the term.[37][38] Christian anarchist groups have included the Doukhobors, Catholic Worker Movement and the Brotherhood Church.

Christian communism is a form of religious communism based on Christianity. It is a theological and political theory based upon the view that the teachings of Jesus Christ compel Christians to support communism as the ideal social system. Although there is no universal agreement on the exact date when Christian communism was founded, many Christian communists assert that evidence from the Bible (in the Acts of the Apostles)[39] suggests that the first Christians, including the apostles, established their small communist society in the years following Jesus' death and resurrection.[39] Many advocates of Christian communism argue that it was taught by Jesus and practised by the apostles.[40] Some independent historians confirm it.[41][42][43][44][45][46][47][48][49][50][51][52]

Islamic socialism

[edit]Islamic socialism incorporates Islamic principles into socialism. As a term, it was coined by various Muslim leaders to describe a more spiritual form of socialism. Scholars have highlighted the similarities between the Islamic economic system and socialist theory, as socialism and Islam are against unearned income. Muslim socialists believe that the teachings of the Quran and Muhammad—especially the zakat—are compatible with the principles of socialism. They draw inspiration from the early Medinan welfare state established by Muhammad. Muslim socialists found their roots in anti-imperialism. Muslim socialist leaders believe in the derivation of legitimacy from the public.

Islamic socialism is the political ideology of Libya's Muammar al-Gaddafi, former Iraqi president Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr, Syrian president Hafez Al-Assad, and Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, the Pakistani leader of the Pakistan Peoples Party. The Green Book, written by Gaddafi, consists of three parts, namely "The Solution of the Problem of Democracy: 'The Authority of the People'", "The Solution of the Economic Problem: 'Socialism'" and "The Social Basis of the Third Universal Theory". The book is controversial because it completely rejects modern conceptions of liberal democracy and encourages the institution of a form of direct democracy based on popular committees. Critics charge that Qaddafi uses these committees as tools of autocratic political repression in practice.

Jewish socialism

[edit]The Jewish left consists of Jews who identify with, or support, left-wing or liberal causes consciously as Jews, either as individuals or through organizations, although there is no single organization or movement which constitutes the Jewish left. Jews have been major forces in the history of the labour movement, the settlement house movement, the women's rights movement, anti-racist and anti-colonialist work and anti-fascist and anti-capitalist organizations of many forms in Europe, the United States, Algeria, Iraq, Ethiopia, and modern-day Israel.[53][54][55][56] Jews have a rich history of involvement in anarchism, socialism, Marxism and Western liberalism. Although the expression "on the left" covers a range of politics, many well-known figures "on the left" have been Jews who were born into Jewish families and have various degrees of connection to Jewish communities, Jewish culture, Jewish tradition, or the Jewish religion in its many variants.

Labor Zionism or socialist Zionism[57] (Hebrew: צִיּוֹנוּת סוֹצְיָאלִיסְטִית, translit. Tziyonut sotzyalistit; Hebrew: תְּנוּעָת הָעַבוֹדָה translit. Tnu'at ha'avoda, i.e. The labor movement) is the left-wing of the Zionist movement. It was the most significant tendency among Zionists and Zionist organizations. It saw itself as the Zionist sector of Eastern and Central Europe's historic Jewish labour movements, eventually developing local units in most countries with sizable Jewish populations. Unlike the "political Zionist" tendency founded by Theodor Herzl and advocated by Chaim Weizmann, Labor Zionists did not believe that a Jewish state would be created simply by appealing to the international community or a powerful nation such as Britain, Germany or the Ottoman Empire. Instead, Labor Zionists believed that a Jewish state could only be created through the efforts of the Jewish working class settling in the Land of Israel and constructing a state through creating a progressive Jewish society with rural kibbutzim and moshavim and an urban Jewish proletariat.[citation needed]

Labor Zionism grew in size and influence and eclipsed "political Zionism" by the 1930s internationally and within the British Mandate of Palestine, where Labor Zionists predominated among many of the institutions of the pre-independence Jewish community Yishuv, particularly the trade union federation known as the Histadrut. The Haganah, the largest Zionist paramilitary defence force, was a Labor Zionist institution and was used on occasion (such as during the Hunting Season) against right-wing political opponents or to assist the British Administration in capturing rival Jewish militants. Labor Zionists played a leading role in the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, and Labor Zionists were predominant among the leadership of the Israeli Defense Force for decades after the formation of the state of Israel in 1948.[citation needed]

Prominent theoreticians of the Labor Zionist movement included Moses Hess, Nachman Syrkin, Ber Borochov, and Aaron David Gordon, and leading figures in the movement included David Ben-Gurion, Golda Meir and Berl Katznelson.

References

[edit]- ^ Ball, Terence; Dagger, Richard; et al. (30 April 2020). "Socialism". Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

- ^ The Gospels, by Terry Eagleton, 2007.

- ^ "Labour revives faith in Christian Socialism". 21 May 1994.

- ^ Oxford Encyclopedia of the Modern Islamic World. New York: Oxford University Press. 1995. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-19-506613-5. OCLC 94030758.

- ^ "Abu Dharr al-Ghifari". Oxford Islamic Studies Online. Archived from the original on 18 June 2013. Retrieved 23 January 2010.

- ^ And Once Again Abu Dharr. Retrieved 15 August 2011.

- ^ Hanna, Sami A.; George H. Gardner (1969). Arab Socialism: A Documentary Survey. Leiden: E.J. Brill. pp. 273–74.

- ^ Hanna, Sami A. (1969). "al-Takaful al-Ijtimai and Islamic Socialism". The Muslim World. 59 (3–4): 275–86. doi:10.1111/j.1478-1913.1969.tb02639.x. Archived from the original on 13 September 2010.

- ^ Janzen, Rod; Stanton, Max (2010). The Hutterites in North America (illustrated ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 17. ISBN 9780801899256.

- ^ Williams, Raymond (1976). Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society. Fontana. ISBN 978-0-00-633479-8.

- ^ Engels, Frederick, Preface to the 1888 English Edition of the Communist Manifesto, p. 202. Penguin (2002).

- ^ a b Houlden, Leslie; Minard, Antone (2015). Jesus in History, Legend, Scripture, and Tradition: A World Encyclopedia: A World Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. p. 357. ISBN 9781610698047.

- ^ Halfin, Igal (2000). From Darkness to Light: Class, Consciousness, and Salvation in Revolutionary Russia. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 46. ISBN 0822957043.

- ^ "Essenes". Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- ^ Kaufmann Kohler. "ESSENES".

- ^ Yosef Gorni; Iaácov Oved; Idit Paz (1987). Communal Life: An International Perspective.

- ^ J. C. Davis (28 July 1983). Utopia and the Ideal Society: A Study of English Utopian Writing 1516–1700. Cambridge University Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-521-27551-4.

- ^ Campbell, Heather M, ed. (2009). The Britannica Guide to Political Science and Social Movements That Changed the Modern World. The Rosen Publishing Group. pp. 127–129. ISBN 978-1-61530-062-4.

- ^ E.g. "That we may work in righteousness, and lay the Foundation of making the Earth a Common Treasury for All, both Rich and Poor, That every one that is born in the Land, may be fed by the Earth his Mother that brought him forth, according to the Reason that rules in the Creation. Not Inclosing any part into any particular hand, but all as one man, working together, and feeding together as Sons of one Father, members of one Family; not one Lording over another, but all looking upon each other, as equals in the Creation;" in The True Levellers Standard A D V A N C E D: or, The State of Community opened, and Presented to the Sons of Men

- ^ Peter Stearns; Cissie Fairchilds; Adele Lindenmeyr; Mary Jo Maynes; Roy Porter; Pamela radcliff; Guido Ruggiero, eds. (2001). Encyclopedia of European Social History: From 1350 to 2000 – Volume 3. Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 290. ISBN 0-684-80577-4.

- ^ Eduard Bernstein (1930). Cromwell and Communism. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- ^ Daniel Roche (1993). La France des Lumières.

- ^ Little, Daniel (17 May 2009). "Marx and the Taipings". China Beat Archive. University of Nebraska–Lincoln. Retrieved 5 August 2020. "Mao and the Chinese Communists largely represented the Taiping rebellion as a proto-communist uprising."

- ^ Shields, James Mark; Liberation as Revolutionary Praxis: Rethinking Buddhist Materialism; Journal of Buddhist Ethics. Volume 20, 2013.

- ^ a b "What is Dhammic Socialism?".

- ^ a b c Tikhonov, Vladimir, Han Yongun's Buddhist Socialism in the 1920s–1930s, International Journal of Buddhist Thought and Culture 6, 207–228 (2006). PDF

- ^ Shields, James Mark; Blueprint for Buddhist Revolution The Radical Buddhism of Seno'o Girō (1889–1961) and the Youth League for Revitalizing Buddhism, Japanese Journal of religious Studies 39 (2), 331–351 (2012) PDF

- ^ Rambelli, Fabio (2013). Zen Anarchism: The Egalitarian Dharma of Uchiyama Gudō. Institute of Buddhist Studies and BDK America, Inc.

- ^ Cambodia Under the Khmer Rouge

- ^ Kershaw, Roger (4 January 2002). Monarchy in South East Asia: The Faces of Tradition in Transition. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780203187845 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Dhammic Socialism Political Thought of Buddhadasa Bhikku, Chulalangkorn Journal of Buddhist Studies 2 (1), page 118 (2003) PDF

- ^ "Dalai Lama Answers Questions on Various Topics". hhdl.dharmakara.net.

- ^ "Political Spectrum as seen by the Social Democratic Party of America".

- ^ Christoyannopoulos, Alexandre (2010). Christian Anarchism: A Political Commentary on the Gospel. Exeter: Imprint Academic. pp. 2–4.

Locating Christian anarchism...In political theology

- ^ Christoyannopoulos, Alexandre (March 2010). "A Christian Anarchist Critique of Violence: From Turning the Other Cheek to a Rejection of the State" (PDF). Political Studies Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 August 2011.

- ^ Christoyannopoulos, Alexandre (2010). Christian Anarchism: A Political Commentary on the Gospel. Exeter: Imprint Academic. pp. 19 and 208.

Leo Tolstoy

- ^ William Thomas Stead, ed. (1894). The review of reviews, Volume 9, 1894, p.306.

- ^ Mather & Crowther, ed. (1894). The Speaker, Volume 9, 1894, p.254.

- ^ a b Acts 2:44, 4:32–37; 5:1–12. Other verses are: Matthew 5:1–12, 6:24, Luke 3:11, 16:11, 2 Corinthians 8:13–15 and James 5:3.

- ^ This is the standpoint of the orthodox Marxist Kautsky, Karl (1953) [1908]. "IV.II. The Christian Idea of the Messiah. Jesus as a Rebel.". Foundations of Christianity. Russell and Russell.

Christianity was the expression of class conflict in Antiquity.

- ^ Gustav Bang Crises in European History p. 24.

- ^ Lansford, Tom (2007). "History of Communism". Communism. Political Systems of the World. Marshall Cavendish. pp. 24–25. ISBN 9780761426288. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

- ^ von Mises, Ludwig (1981) [1951]. "Christianity and Socialism". Socialism. New Heaven: Yale University Press. p. 424. ISBN 9780913966624. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

- ^ "Rénan's Les Apôtres. Community life". The London Quarterly and Holborn Review, Volume 26. London. 1866 [April and July]. p. 502. Retrieved 10 May 2011.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Unterbrink, Daniel T. (2004). "The Dead Sea Scrolls". Judas the Galilean. Lincoln: iUniverse. p. 92. ISBN 0-595-77000-2. Retrieved 10 May 2011.

- ^ Guthrie, Donald (1992) [1975]. "3. Early Problems. 15. Early Christian Communism". The Apostles. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-310-25421-8.

- ^ Renan, Ernest (1869). "VIII. First Persecution. Death of Stephen. Destruction of the First Church of Jerusalem". Origins of Christianity. Vol. II. The Apostles. New York: Carleton. p. 152.

- ^ Ehrhardt, Arnold (1969). "St Peter and the Twelve". The Acts of the Apostles. Manchester: University of Manchester. The University Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0719003820.

- ^ Boer, Roland (2009). "Conclusion: What If? Calvin and the Spirit of Revolution. Bible". Political Grace. The Revolutionary Theology of John Calvin. Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster John Knox Press. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-664-23393-8.

- ^ Halteman Finger, Reta (2007). "Reactions to Style and Redaction Criticism". Of Widows and Meals. Communal Meals in the Book of Acts. Cambridge, UK: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-8028-3053-1.

- ^ Ellicott, Charles John; Plumptre, Edward Hayes (1910). "III. The Church in Jerusalem. I. Christian Communism". The Acts of the Apostles. London: Cassell.

- ^ Montero, Roman A. (2017). All Things in Common The Economic Practices of the Early Christians. Foster, Edgar G. Eugene: Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 9781532607912. OCLC 994706026.

- ^ "The New Left." Jewish Virtual Library (2008); retrieved 6 June 2015.

- ^ "Henri Alleg, auteur de "La Question", est mort". Le Monde.fr. 18 July 2013 – via Le Monde.

- ^ Naeim Giladi, "The Jews of Iraq": "In many countries, including the United States and Iraq, Jews represented a large part of the Communist party. In Iraq, hundreds of Jews of the working intelligentsia occupied key positions in the hierarchy of the Communist and Socialist parties."

- ^ Hannah Borenstein, "Savior Story": "The violence of the late 1970s and early 1980s Ethiopia spurred many forms of active and comprehensive resistance. Ethiopian Jews participated widely; many, for instance, were members of the Marxist-Leninist EPRP."

- ^ "Socialist Zionism". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 19 August 2014.