Calculus ratiocinator

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (May 2010) |

The calculus ratiocinator is a theoretical universal logical calculation framework, a concept described in the writings of Gottfried Leibniz, usually paired with his more frequently mentioned characteristica universalis, a universal conceptual language.

Two views

[edit]There are two contrasting points of view on what Leibniz meant by calculus ratiocinator. The first is associated with computer software, the second is associated with computer hardware.

Analytic view

[edit]The received point of view in analytic philosophy and formal logic, is that the calculus ratiocinator anticipates mathematical logic—an "algebra of logic".[1] The analytic point of view understands that the calculus ratiocinator is a formal inference engine or computer program, which can be designed so as to grant primacy to calculations. That logic began with Frege's 1879 Begriffsschrift and C.S. Peirce's writings on logic in the 1880s. Frege intended his "concept script" to be a calculus ratiocinator as well as a universal characteristics. That part of formal logic relevant to the calculus comes under the heading of proof theory. From this perspective the calculus ratiocinator is only a part (or a subset) of the universal characteristics, and a complete universal characteristics includes a "logical calculus".

Synthetic view

[edit]A contrasting point of view stems from synthetic philosophy and fields such as cybernetics, electronic engineering, and general systems theory. It is little appreciated in analytic philosophy. The synthetic view understands the calculus ratiocinator as referring to a "calculating machine". The cybernetician Norbert Wiener considered Leibniz's calculus ratiocinator a forerunner to the modern day digital computer:

"The history of the modern computing machine goes back to Leibniz and Pascal. Indeed, the general idea of a computing machine is nothing but a mechanization of Leibniz's calculus ratiocinator."

— Wiener (1948, p. 214)

"...like his predecessor Pascal, [Leibniz] was interested in the construction of computing machines in the Metal. ... just as the calculus of arithmetic lends itself to a mechanization progressing through the abacus and the desk computing machine to the ultra-rapid computing machines of the present day, so the calculus ratiocinator of Leibniz contains the germs of the machina ratiocinatrix, the reasoning machine."

— Wiener (1965, p. 12)

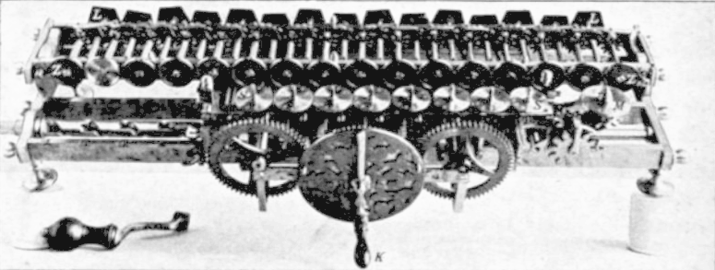

Leibniz constructed just such a machine for mathematical calculations, which was also called a "stepped reckoner". As a computing machine, the ideal calculus ratiocinator would perform Leibniz's integral and differential calculus. In this way the meaning of the word, "ratiocinator" is clarified and can be understood as a mechanical instrument that combines and compares ratios.

-

Internal mechanism of the stepped reckoner

-

Contemporary replica of the stepped reckoner

Hartley Rogers saw a link between the two, defining the calculus ratiocinator as "an algorithm which, when applied to the symbols of any formula of the characteristica universalis, would determine whether or not that formula were true as a statement of science".[2]

A classic discussion of the calculus ratiocinator is that of Louis Couturat,[3] who maintained that the characteristica universalis — and thus the calculus ratiocinator — were inseparable from Leibniz's encyclopedic project.[4] Hence the characteristics, calculus ratiocinator, and encyclopedia form three pillars of Leibniz's project.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Fearnley-Sander (1982), p. 164.

- ^ Rogers (1963), p. 934.

- ^ Couturat (1901), chapters 3, 4.

- ^ Couturat (1901), chapter 5.

Bibliography

[edit]- Couturat, Louis (1901). La Logique de Leibniz. Translated by Rutherford, Donald. Paris: Felix Alcan. Archived from the original on 2012-08-14.

- Rogers, Hartley Jr. (1963). "An Example in Mathematical Logic". The American Mathematical Monthly. 70 (9): 929–945. doi:10.1080/00029890.1963.11992146.

- Wiener, Norbert (1948). "Time, communication, and the nervous system". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 50 (4): 197–219. Bibcode:1948NYASA..50..197W. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1948.tb39853.x. PMID 18886381. S2CID 28452205.

- Wiener, Norbert (1965). Cybernetics or the Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine (2, paperback ed.). The MIT Press.

- Fearnley-Sander, Desmond (1982). "Hermann Grassmann and the Prehistory of Universal Algebra". The American Mathematical Monthly. 89 (3): 161–166. doi:10.1080/00029890.1982.11995404.