History of Djibouti

| History of Djibouti |

|---|

|

| Prehistory |

| Antiquity |

|

| Middle Ages |

|

| Colonial period |

|

| Modern period |

| Republic of Djibouti |

|

|

Djibouti is a country in the Horn of Africa bordered by Somalia to the east, Eritrea to west and the Red Sea to the north, Ethiopia to the west and south, and the Gulf of Aden to the east.

In antiquity, the territory was part of the Land of Punt. Djibouti gained its independence on June 27, 1977. The Djibouti area, along with other localities in the Horn region, was later the seat of the medieval Adal and Ifat Sultanates. In the late 19th century, the colony of French Somaliland was established following treaties signed by the ruling Somali and Afar Sultans with the French. It was subsequently renamed to the French Territory of the Afars and the Issas in 1967. A decade later, the Djiboutian people voted for independence, officially marking the establishment of the Republic of Djibouti.

Prehistory

[edit]

The Bab-el-Mandeb region has often been considered a primary crossing point for early hominins following a southern coastal route from East Africa to South Arabia and Southeast Asia.

Djibouti area has been inhabited since the Neolithic. According to linguists, the first Afroasiatic-speaking populations arrived in the region during this period from the family's proposed urheimat ("original homeland") in the Nile Valley,[1] or the Near East.[2] Other scholars propose that the Afroasiatic family developed in situ in the Horn, with its speakers subsequently dispersing from there.[3]

The cut stones 3 million years old, collected in the area of Lake Abbe.[citation needed] In the Gobaad plain (between Dikhil and Lake Abbe), the remains of an Palaeoloxodon recki elephant were also discovered, visibly butchered using basalt tools found nearby. These remains would date from 1.4 million years BC.[citation needed] Subsequently identified other sites of these cuts, probably the work of Homo ergaster. An Acheulean site (from 800,000 to 400,000 years BC), where stone was cut, was excavated in the 1990s[citation needed], in Gombourta, between Damerdjog and Loyada, 15 km south of Djibouti. Finally, in Gobaad, a Homo erectus jaw was found, dating from 100,000 BC. AD On Devil's Island, tools dating back 6,000 years have been found, which were no doubt used to open shells. In the area at the bottom of Goubet (Dankalélo, not far from Devil's Island), circular stone structures and fragments of painted pottery have also been discovered. Previous investigators have also reported a fragmentary maxilla, attributed to an older form of Homo sapiens and dated to ~250 Ka, from the valley of the Dagadlé Wadi.

Pottery predating the mid-2nd millennium has been found at Asa Koma, an inland lake area on the Gobaad Plain. The site's ware is characterized by punctate and incision geometric designs, which bear a similarity to the Sabir culture phase 1 ceramics from Ma'layba in Southern Arabia.[4] Long-horned humpless cattle bones have likewise been discovered at Asa Koma, suggesting that domesticated cattle were present by around 3,500 years ago.[5] Rock art of what appear to be antelopes and a giraffe are also found at Dorra and Balho.[6] Handoga, dated to the fourth millennium BP, has in turn yielded obsidian microliths and plain ceramics used by early nomadic pastoralists with domesticated cattle.[7]

The site of Wakrita is a small Neolithic establishment located on a wadi in the tectonic depression of Gobaad in Djibouti in the Horn of Africa. The 2005 excavations yielded abundant ceramics that enabled us to define one Neolithic cultural facies of this region, which was also identified at the nearby site of Asa Koma. The faunal remains confirm the importance of fishing in Neolithic settlements close to Lake Abbé, but also the importance of bovine husbandry and, for the first time in this area, evidence for caprine herding practices. Radiocarbon dating places this occupation at the beginning of the 2nd millennium BC, similar in range to Asa Koma. These two sites represent the oldest evidence of herding in the region, and they provide a better understanding of the development of Neolithic societies in this region.

Up to 4000 years BC. AD, the region benefited from a climate very different from the one it knows today and probably close to the Mediterranean climate. The water resources were numerous: lakes in the Gobaad, lakes Assal and Abbé larger and resembling real bodies of water. The humans therefore lived by gathering, fishing and hunting. The region was populated by a very rich fauna: felines, buffaloes, elephants, rhinos, etc., as evidenced, for example, by the bestiary of cave paintings at Balho. In the 3rd and 2nd millennia BC. A few nomads settled around the lakes and practiced fishing and cattle breeding. The burial of an 18-year-old woman, dating from this period, as well as the bones of hunted animals, bone tools and small jewels have been unearthed. About 1500 BC. AD, the climate is already changing, water is scarce. Engravings show dromedaries (animal of arid zones), some of which are ridden by armed warriors. Sedentary peoples return to Nomadic life. A stone tumuli (of various shapes), sheltering graves and dating from this period, have been unearthed all over the territory.

Antiquity

[edit]

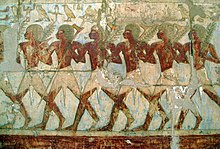

Together with Somaliland, Eritrea and the Red Sea coast of Sudan, Djibouti is considered the most likely location of the land known to the ancient Egyptians as Punt (or "Ta Netjeru", meaning "God's Land"). The old territory's first mention dates to the 25th century BC.[8] The Puntites were a nation of people that had close relations with Ancient Egypt during the times of Pharaoh Sahure of the fifth dynasty and Queen Hatshepsut of the eighteenth dynasty. They "traded not only in their own produce of incense, ebony and short-horned cattle, but also in goods from other neighbouring regions, including gold, ivory and animal skins."[9] According to the temple reliefs at Deir el-Bahari, the Land of Punt at the time of Hatshepsut was ruled by King Parahu and Queen Ati.[10]

Macrobians

[edit]The Macrobians (Μακροβίοι) were a legendary people and kingdom positioned in the Horn of Africa mentioned by Herodotus. Later authors (such as Pliny on the authority of Ctesias' Indika) place them in India instead. It is one of the legendary peoples postulated at the extremity of the known world (from the perspective of the Greeks), in this case in the extreme south, contrasting with the Hyperboreans in the extreme east.

Their name is due to their legendary longevity; an average person supposedly living to the age of 120.[11] They were said to be the "tallest and handsomest of all men".[12]

According to Herodotus' account, the Persian Emperor Cambyses II upon his conquest of Egypt (525 BC) sent ambassadors to Macrobia, bringing luxury gifts for the Macrobian king to entice his submission. The Macrobian ruler, who was elected based at least in part on stature, replied instead with a challenge for his Persian counterpart in the form of an unstrung bow: if the Persians could manage to string it, they would have the right to invade his country; but until then, they should thank the gods that the Macrobians never decided to invade their empire.[12][13]

Kingdom of Aksum

[edit]The rule of the Aksumite Kingdom may have at times extended to areas that are now within Djibouti, though the nature and extent of its control are not clear.[14]

Ifat Sultanate

[edit]The Ifat Sultanate was a medieval kingdom in the Horn of Africa. Founded in 1285 by the Walashma dynasty, it was centered in Zeila.[15][16] Ifat established bases in Djibouti and Somaliland, and from there expanded southward to the Ahmar Mountains. Its Sultan Umar Walashma (or his son Ali, according to another source) is recorded as having conquered the Sultanate of Shewa in 1285. Taddesse Tamrat explains Sultan Umar's military expedition as an effort to consolidate the Muslim territories in the Horn, in much the same way as Emperor Yekuno Amlak was attempting to unite the Christian territories in the highlands during the same period. These two states inevitably came into conflict over Shewa and territories further south. A lengthy war ensued, but the Muslim sultanates of the time were not strongly unified. Ifat was finally defeated by Emperor Amda Seyon I of Ethiopia in 1332, and withdrew from Shewa.

Adal Sultanate

[edit]Islam was introduced to the area early on from the Arabian peninsula, shortly after the hijra. Zeila's two-mihrab Masjid al-Qiblatayn dates to the 7th century, and is the oldest mosque in the city.[17] In the late 9th century, Al-Yaqubi wrote that Muslims were living along the northern Horn seaboard.[18] He also mentioned that the Adal kingdom had its capital in Zeila, a port city in the northwestern Awdal region abutting Djibouti.[18][19] This suggests that the Adal Sultanate with Zeila as its headquarters dates back to at least the 9th or 10th century. According to I.M. Lewis, the polity was governed by local dynasties consisting of Somalized Arabs or Arabized Somalis, who also ruled over the similarly established Sultanate of Mogadishu in the Benadir region to the south. Adal's history from this founding period forth would be characterized by a succession of battles with neighbouring Abyssinia.[19] At its height, the Adal kingdom controlled large parts of modern-day Djibouti, Somaliland, Eritrea and Ethiopia. Between Djibouti City and Loyada are a number of anthropomorphic and phallic stelae. The Djibouti-Loyada stelae are of uncertain age, and some of them are adorned with a T-shaped symbol.[20] Additionally, archaeological excavations at Tiya have yielded tombs.[21] As of 1997, 118 stelae were reported in the area.

Egypt Eyalet

[edit]Governor Abou Baker ordered the Egyptian garrison at Sagallo to retire to Zeila. The cruiser Seignelay reached Sagallo shortly after the Egyptians had departed. French troops occupied the fort despite protests from the British Agent in Aden, Major Frederick Mercer Hunter, who dispatched troops to safeguard British and Egyptian interests in Zeila and prevent further extension of French influence in that direction.[22] On 14 April 1884 the Commander of the patrol sloop L’Inferent reported on the Egyptian occupation in the Gulf of Tadjoura. The Commander of the patrol sloop Le Vaudreuil reported that the Egyptians were occupying the interior between Obock and Tadjoura. Emperor Johannes IV of Ethiopia signed an accord with the United Kingdom to cease fighting the Egyptians and to allow the evacuation of Egyptian forces from Ethiopia and the Somali Coast ports. The Egyptian garrison was withdrawn from Tadjoura. Léonce Lagarde deployed a patrol sloop to Tadjoura the following night.

French Somaliland

[edit]

The boundaries of the present-day Djibouti nation state were established during the Scramble for Africa. It was Rochet d'Hericourt's exploration into Shoa (1839–42) that marked the beginning of French interest in the Djiboutian coast of the Red Sea. Further exploration by Henri Lambert, French Consular Agent at Aden, and Captain Fleuriot de Langle led to a treaty of friendship and assistance between France and the sultans of Raheita, Tadjoura, and Gobaad, from whom the French purchased the anchorage of Obock in 1862.

Growing French interest in the area took place against a backdrop of British activity in Egypt and the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869. Between 1883 and 1887, France signed various treaties with the then ruling Somali and Afar Sultans, which allowed it to expand the protectorate to include the Gulf of Tadjoura.[23] Léonce Lagarde was subsequently installed as the protectorate's governor. In 1894, he established a permanent French administration in the city of Djibouti and named the region Côte française des Somalis (French Somaliland), a name which continued until 1967. The territory's border with Ethiopia, marked out in 1897 by France and Emperor Menelik II of Ethiopia, was later reaffirmed by agreements with Emperor Haile Selassie I of Ethiopia in 1945 and 1954.

In 1889, a Russian by the name of Nikolay Ivanovitch Achinov[24][25] (b. 1856[26]), arrived with settlers, infantry and an Orthodox priest to Sagallo on the Gulf of Tadjoura. The French considered the presence of the Russians as a violation of their territorial rights and dispatched two gunboats. The Russians were bombarded and after some loss of life, surrendered. The colonists were deported to Odessa and the dream of Russian expansion in East Africa came to an end in less than one year.

The administrative capital was moved from Obock in 1896. The city of Djibouti, which had a harbor with good access that attracted trade caravans crossing East Africa, became the new administrative capital. The Franco-Ethiopian railway, linking Djibouti to the heart of Ethiopia, began in 1897 and reached Addis Ababa in June 1917, increasing the volume of trade passing through the port.

World War II

[edit]After the Italian invasion and occupation of Ethiopia in the mid-1930s, constant border skirmishes occurred between French forces in French Somaliland and Italian forces in Italian East Africa. In June 1940, during the early stages of World War II, France fell and the colony was then ruled by the pro-Axis Vichy (French) government while the Italians occupied some areas of the French Somaliland.

Indeed, the Italians did undertake some offensive actions beginning on 18 June 1940, occupying nearly one third of French Somaliland in a few days.[27]

From Harrar Governorate, troops under General Guglielmo Nasi attacked the fort of Ali-Sabieh in the south and Dadda'to in the north. There were also skirmishes in the area of Dagguirou and around the lakes Abbe and Ally.[28] Near Ali-Sabieh, there was some skirmishing over the Djibouti–Addis Ababa railway.[29] In the first week of war, the Italian Navy sent the submarines Torricelli and Perla to patrol French territorial waters in the Gulf of Tadjoura in front of the ports of Djibouti, Tadjoura and Obock.[30][a]

By the end of June the Italians had also occupied the border fortifications of Magdoul, Daimoli, Balambolta, Birt Eyla, Asmailo, Tewo, Abba, Alailou, Madda and Rahale.[31]

Later, British and Commonwealth forces fought the neighboring Italians during the East African Campaign. In 1941, the Italians were defeated and the Vichy forces in French Somaliland were isolated. The Vichy French administration continued to hold out in the colony for over a year after the Italian collapse. In response, the British blockaded the port of Djibouti City but it could not prevent local French from providing information on the passing ship convoys. In 1942, about 4,000 British troops occupied the city. A local battalion from French Somaliland participated in the Liberation of Paris in 1944.

Referendums

[edit]In 1958, on the eve of neighboring Somalia's independence in 1960, a referendum was held in Djibouti to decide whether to be an independent country or to remain with France. The referendum turned out in favour of a continued association with France, partly due to a combined yes vote by the sizable Afar ethnic group and resident Europeans.[32] There were also reports of widespread vote rigging, with the French expelling thousands of Somalis before the referendum reached the polls.[33] The majority of those who voted no were Somalis who were strongly in favour of joining a united Somalia as had been proposed by Mahmoud Harbi, Vice President of the Government Council. Harbi died in a plane crash two years later under mysterious circumstances.[32][34]

In 1960, with the fall of the ruling Dini administration, Ali Aref Bourhan, a Harbist politician, assumed the seat of Vice President of the Government Council of French Somaliland, representing the UNI party.[35] He would hold that position until 1966.

That same year, France rejected the United Nations' recommendation that it should grant French Somaliland independence. In August, an official visit to the territory by then French President, General Charles de Gaulle, was also met with demonstrations and rioting.[36][37] In response to the protests, de Gaulle ordered another referendum.[37]

On 19 March 1967, a second plebiscite was held to determine the fate of the territory. Initial results supported a continued but looser relationship with France. Voting was also divided along ethnic lines, with the resident Somalis generally voting for independence, with the goal of eventual reunion with Somalia, and the Afars largely opting to remain associated with France.[36] However, the referendum was again marred by reports of vote rigging on the part of the French authorities,[38] with some 10,000 Somalis deported under the pretext that they did not have valid identity cards.[39] According to official figures, although the territory was at the time inhabited by 58,240 Somali and 48,270 Afar, only 14,689 Somali were allowed to register to vote versus 22,004 Afar.[40] Somali representatives also charged that the French had simultaneously imported thousands of Afar nomads from neighboring Ethiopia to further tip the odds in their favor, but the French authorities denied this, suggesting that Afars already greatly outnumbered Somalis on the voting lists.[39] Announcement of the plebiscite results sparked civil unrest, including several deaths. France also increased its military force along the frontier.[39][41]

French Territory of the Afars and Issas

[edit]In 1967, shortly after the second referendum was held, the former Côte française des Somalis (French Somaliland) was renamed to Territoire français des Afars et des Issas. This was both in acknowledgement of the large Afar constituency and to downplay the significance of the Somali composition (the Issa being a Somali sub-clan).[41]

The French Territory of Afars and Issas also differed from French Somaliland in terms of government structure, as the position of governor changed to that of high commissioner. A nine-member council of government was also implemented. During the 1960s, the struggle for independence was led by the Front for the Liberation of the Somali Coast (FLCS), who waged an armed struggle for independence with much of its violence aimed at French personnel. FLCS used to initiate few mounting cross-border operations into French Somaliland from Somalia and Ethiopia to attacks on French targets. On 24 March 1975 the Front de Libération de la Côte des Somalis kidnapped the French Ambassador to Somalia, Jean Guery, to be exchanged against two activists of FLCS members who were both serving life terms in mainland France. He was exchanged for the two FLCS members in Aden, South Yemen.[42] With a steadily enlarging Somali population, the likelihood of a third referendum appearing successful had grown even more dim. The prohibitive cost of maintaining the colony and the fact that after 1975, France found itself to be the last remaining colonial power in Africa was another factor that compelled observers to doubt that the French would attempt to hold on to the territory.

In 1976, the French garrison, centered on the 13th Demi-Brigade of the Foreign Legion (13 DBLE), had to be reinforced to contain Somali irredentist aspirations, revolting against the French-engineered Afar domination of the emerging government.[43] In 1976, members of the Front de Libération de la Côte des Somalis which sought Djibouti's independence from France, also clashed with the Gendarmerie Nationale Intervention Group over a bus hijacking en route to Loyada.

The FLCS was recognized as a national liberation movement by the Organization of African Unity (OAU), which participated in its financing. The FLCS evolved its demands between the request of integration in a possible "Greater Somalia" influenced by the Somali government or the simple independence of the territory. In 1975 the African People's League for the Independence (LPAI) and FLCS met in Kampala, Uganda with several meeting later they finally opted for independence path, causing tensions with Somalia.[44]

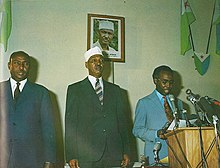

A third independence referendum was held in the French Territory of the Afars and the Issas on 8 May 1977. The previous referendums were held in 1958 and 1967,[45][38] which rejected independence. This referendum backed independence from France.[46] A landslide 98.8% of the electorate supported disengagement from France, officially marking Djibouti's independence.

After independence the new government signed an agreement calling for a strong French garrison, though the 13 DBLE was envisaged to be withdrawn.[43] While the unit was reduced in size, a full withdrawal never actually took place.

Djibouti Republic

[edit]In 1981, Aptidon turned the country into a one party state by declaring that his party, the Rassemblement Populaire pour le Progrès (RPP) (People's Rally for Progress), was the sole legal one. Clayton writes that the French garrison played the major role in suppressing further minor unrest about this time, during which Djibouti became a one-party state on a much broader ethnic and political basis.[43]

A civil war broke out in 1991, between the government and a predominantly Afar rebel group, the Front for the Restoration of Unity and Democracy (FRUD). The FRUD signed a peace accord with the government in December 1994, ending the conflict. Two FRUD members were made cabinet members, and in the presidential elections of 1999 the FRUD campaigned in support of the RPP.

Aptidon resigned as president 1999, at the age of 83, after being elected to a fifth term in 1997. His successor was his nephew, Ismail Omar Guelleh.

On 12 May 2001, President Ismail Omar Guelleh presided over the signing of what is termed the final peace accord officially ending the decade-long civil war between the government and the armed faction of the FRUD, led by Ahmed Dini Ahmed, an Afar nationalist and former Gouled political ally. The peace accord successfully completed the peace process begun on 7 February 2000 in Paris. Ahmed Dini Ahmed represented the FRUD.[47]

In the presidential election held 8 April 2005, Ismail Omar Guelleh was re-elected to a second 6-year term at the head of a multi-party coalition that included the FRUD and other major parties. A loose coalition of opposition parties again boycotted the election. Currently, political power is shared by a Somali president and an Afar prime minister, with an Afar career diplomat as Foreign Minister and other cabinet posts roughly divided. However, Issas are predominate in the government, civil service, and the ruling party. That, together with a shortage of non-government employment, has bred resentment and continued political competition between the Issa Somalis and the Afars. In March 2006, Djibouti held its first regional elections and began implementing a decentralization plan. The broad pro-government coalition, including FRUD candidates, again ran unopposed when the government refused to meet opposition preconditions for participation. In the 2008 elections, the opposition Union for a Presidential Majority (UMP) party boycotted the election, leaving all 65 seats to the ruling RPP. Voter turnout figures were disputed. Guelleh was re-elected in the 2011 presidential election.[48]

Due to its strategic location at the mouth of the Bab el Mandeb gateway to the Red Sea and the Suez Canal, Djibouti also hosts various foreign military bases. Camp Lemonnier is a United States Naval Expeditionary Base,[49] situated at Djibouti-Ambouli International Airport and home to the Combined Joint Task Force - Horn of Africa (CJTF-HOA) of the U.S. Africa Command (USAFRICOM).[50] In 2011, Japan also opened a local naval base staffed by 180 personnel to assist in marine defense. This initiative is expected to generate $30 million in revenue for the Djiboutian government.[51]

In April 2021, Ismael Guelleh, the second President of Djibouti since independence from France in 1977, was re-elected for his fifth term.[52]

See also

[edit]- Colonial heads of Djibouti (French Somaliland)

- French Territory of the Afars and the Issas (FTAI)

- French Somaliland

- Heads of government of Djibouti

- History of Africa

- List of presidents of Djibouti

- Politics of Djibouti

- Djibouti City history and timeline

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ For further information, see Red Sea Flotilla.

References

[edit]- Citations

- ^ Zarins, Juris (1990), "Early Pastoral Nomadism and the Settlement of Lower Mesopotamia", (Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research)

- ^ Diamond J, Bellwood P (2003) Farmers and Their Languages: The First Expansions SCIENCE 300, doi:10.1126/science.1078208

- ^ Blench, R. (2006). Archaeology, Language, and the African Past. Rowman Altamira. pp. 143–144. ISBN 978-0759104662. Archived from the original on 14 September 2014. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- ^ Walter Raunig, Steffen Wenig (2005). Afrikas Horn. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 439. ISBN 978-3447051750. Archived from the original on 14 September 2014. Retrieved 7 September 2014.

- ^ Connah, Graham (2004). Forgotten Africa: An Introduction to Its Archaeology. Routledge. p. 46. ISBN 978-1134403035. Archived from the original on 14 September 2014. Retrieved 7 September 2014.

- ^ Universität Frankfurt am Main (2003). Journal of African Archaeology, Volumes 1–2. Africa Manga Verlag. p. 230. ISBN 9783937248004. Archived from the original on 14 September 2014. Retrieved 7 September 2014.

- ^ Finneran, Niall (2013). The Archaeology of Ethiopia. 1136755527: Routledge. p. 86. ISBN 978-1136755521. Retrieved 29 December 2016.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Simson Najovits, Egypt, trunk of the tree, Volume 2, (Algora Publishing: 2004), p.258.

- ^ Tyldesley, Hatchepsut, p.147

- ^ Breasted 1906–07, pp. 246–295, vol. 1.

- ^ The Geography of Herodotus: Illustrated from Modern Researches and Discoveries by James Talboys Wheeler pg 528. The British Critic, Quarterly Theological Review, And Ecclesiastical Record Volume 11 pg 434

- ^ a b Wheeler pg 526

- ^ John Kitto, James Taylor, The popular cyclopædia of Biblical literature: condensed from the larger work, (Gould and Lincoln: 1856), p.302.

- ^ Seland, Eivind Heldaas (1 December 2014). "Early Christianity in East Africa and Red Sea/Indian Ocean Commerce". African Archaeological Review. 31 (4): 637–647. doi:10.1007/s10437-014-9172-5. hdl:1956/8893. ISSN 1572-9842.

- ^ J. Gordon Melton and Martin Baumann, Religions of the World, Second Edition: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Beliefs and Practices, page 2663

- ^ Asafa Jalata, State Crises, Globalisation, And National Movements In North-east Africa page 3-4

- ^ Briggs, Phillip (2012). Somaliland. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 7. ISBN 978-1841623719.

- ^ a b Encyclopedia Americana, Volume 25. Americana Corporation. 1965. p. 255.

- ^ a b Lewis, I.M. (1955). Peoples of the Horn of Africa: Somali, Afar and Saho. International African Institute. p. 140.

- ^ Fattovich, Rodolfo (1987). "Some remarks on the origins of the Aksumite Stelae" (PDF). Annales d'Éthiopie. 14 (14): 43–69. doi:10.3406/ethio.1987.931. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 7 September 2014.

- ^ "Tiya – Prehistoric site". UNESCO. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- ^ "FRENCH SOMALI COAST 1708 – 1946 FRENCH SOMALI COAST | Awdalpress.com". Archived from the original on 9 June 2013. Retrieved 19 April 2013. FRENCH SOMALI COAST Timeline

- ^ Raph Uwechue, Africa year book and who's who, (Africa Journal Ltd.: 1977), p. 209.

- ^ Ashinov, Achinov, Atchinoff or Atchimoff

- ^ (in French) Le cosaque Achinoff in Le Progrès Illustré (French daily newspaper), 1 March 1891

- ^ Ernest A. Wallis Budge, A history of Ethiopia, Nubia and Abyssinia, Taylor & Francis, 1928.

- ^ further detailed info at simple:Italian invasion of French Somaliland

- ^ Rovighi 1995, p. 107.

- ^ Thompson & Adloff 1968, p. 16.

- ^ Rovighi 1995, p. 105.

- ^ Rovighi 1995, p. 109.

- ^ a b Barrington, Lowell, After Independence: Making and Protecting the Nation in Postcolonial and Postcommunist States, (University of Michigan Press: 2006), p. 115 ISBN 0472068989

- ^ Kevin Shillington, Encyclopedia of African history, (CRC Press: 2005), p. 360 ISBN 1579582451.

- ^ United States Joint Publications Research Service, Translations on Sub-Saharan Africa, Issues 464–492, (1966), p.24.

- ^ Dubois, Colette (2002). "Jacques Foccart et Ali Aref". Les Cahiers du Centre de Recherches Historiques (30). doi:10.4000/ccrh.472.

- ^ a b A Political Chronology of Africa, (Taylor & Francis), p.132.

- ^ a b Newsweek, Volume 81, (Newsweek: 1973), p.254.

- ^ a b American Universities Field Staff, Northeast Africa series, Volume 15, Issue 1, (American Universities Field Staff.: 1968), p.3.

- ^ a b c Jean Strouse, Newsweek, Volume 69, Issues 10–17, (Newsweek: 1967), p.48.

- ^ Africa Research, Ltd, Africa contemporary record: annual survey and documents, Volume 1, (Africana Pub. Co.: 1969), p.264.

- ^ a b Alvin J. Cottrell, Robert Michael Burrell, Georgetown University. Center for Strategic and International Studies, The Indian Ocean: its political, economic, and military importance, (Praeger: 1972), p.166.

- ^ "French Envoy in Somalia Held by Anti-Paris Group". The New York Times. 25 March 1975.

- ^ a b c Clayton 1988, 236.

- ^ Gonidec, Pierre François. African Politics. The Hague: Matinus Nijhoff, 1981. p. 272

- ^ Kevin Shillington, Encyclopedia of African history, (CRC Press: 2005), p.360.

- ^ Nohlen, D, Krennerich, M & Thibaut, B (1999) Elections in Africa: A data handbook, p. 322 ISBN 0-19-829645-2

- ^ "Djibouti (09/06)". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ^ "Djibouti: President Ismael Omar Guelleh wins third term". BBC News. 9 April 2011.

- ^ "Introduction to MARCENT". United States Marine Corps. May 2006. Archived from the original (PPT) on 25 October 2007. Retrieved 9 February 2007.

- ^ "Africans Fear Hidden U.S. Agenda in New Approach to Africom". Associated Press. 30 September 2008. Archived from the original on 2 April 2013. Retrieved 30 September 2008.

- ^ "Japan Opens Military Base in Djibouti to Help Combat Piracy". Bloomberg. 8 July 2011.

- ^ "Djibouti President Guelleh wins election with 98%, provisional results". Africanews.

- Bibliography

- Clayton, Anthony (1988). France, Soldiers, and Africa. Brassey's Defence Publishers.

- Rovighi (1995). Le operazioni in Africa orientale (giugno 1940 – novembre 1941). Volume II: Documenti. Rome: Stato Maggiore dell'Esercito.

- Thompson, Virginia McLean; Adloff, Richard (1968). Djibouti and the Horn of Africa. Stanford University Press.