Rabies in animals

In animals, rabies is a viral zoonotic neuro-invasive disease which causes inflammation in the brain and is usually fatal. Rabies, caused by the rabies virus, primarily infects mammals. In the laboratory it has been found that birds can be infected, as well as cell cultures from birds, reptiles and insects.[1] The brains of animals with rabies deteriorate. As a result, they tend to behave bizarrely and often aggressively, increasing the chances that they will bite another animal or a person and transmit the disease.

In addition to irrational aggression, the virus can induce hydrophobia ("fear of water")—wherein attempts to drink water or swallow cause painful spasms of the muscles in the throat or larynx—and an increase in saliva production. This aids the likelihood of transmission, as the virus multiplies and accumulates in the salivary glands and is transmitted primarily through biting.[2] The accumulation of saliva can sometimes create a "foaming at the mouth" effect, which is commonly associated with rabies in animals in the public perception and in popular culture;[3][4][5] however, rabies does not always present as such, and may be carried without typical symptoms being displayed.[3]

Most cases of humans contracting rabies from infected animals are in developing nations. In 2010, an estimated 26,000 people died from the disease, down from 54,000 in 1990.[6] The World Health Organization (WHO) reports that dogs are the main source of human rabies deaths, contributing up to 99% of all transmissions of the disease to humans.[7] Rabies in dogs, humans and other animals can be prevented through vaccination.

Stages of disease

[edit]Three stages of rabies are recognized in dogs and other animals.

- The first stage, known as the prodromal stage, is a one- to three-day period that occurs once the virus reaches the brain, and enters the beginning of encephalitis. Outwardly, it is characterized by behavioral changes such as restlessness, deep fatigue, and pain indications such as self-biting or itching. Some animals demonstrate more social behavior while others conversely, self-isolate; this is an early warning sign of the pathogen changing the hosts’ behavior to speed up transmission.[8] Physical shifts such as fever, or nausea may also be present. Once this stage is reached, treatment is usually no longer viable. The onset of the prodromal stage can vary significantly, which can be attested to factors such as the strain of the virus, the viral load, the route of transmission, and the distance the virus must travel up the peripheral nerves to the central nervous system. The incubation period can be between months to years in humans but typically averages down to weeks or as little as a day in most mammals.[9]

- The second stage is the excitative stage, which lasts three to four days. It is this stage that is often known as furious rabies due to the tendency of the affected animal to be hyperreactive to external stimuli and bite at anything near.

- The third stage is the paralytic or "dumb" stage and is caused by damage to motor neurons. Incoordination is seen due to rear limb paralysis and drooling and difficulty swallowing is caused by paralysis of facial and throat muscles. This disables the host's ability to swallow, which causes saliva to pour from the mouth. This causes bites to be the most common way for the infection to spread, as the virus is most concentrated in the throat and cheeks, causing major contamination to saliva. Death is usually caused by respiratory arrest.[10]

Mammals

[edit]Bats

[edit]Bat-transmitted rabies occurs throughout North and South America but it was first closely studied in Trinidad in the West Indies. This island was experiencing a significant toll of livestock and humans alike to rabid bats. In the 10 years from 1925 and 1935, 89 people and thousands of livestock had died from it—"the highest human mortality from rabies-infected bats thus far recorded anywhere."[11]

In 1931, Dr. Joseph Lennox Pawan of Trinidad in the West Indies, a government bacteriologist, found Negri bodies in the brain of a bat with unusual habits. In 1932, Dr. Pawan discovered that infected vampire bats could transmit rabies to humans and other animals.[12][13] In 1934, the Trinidad and Tobago government began a program of eradicating vampire bats, while encouraging the screening off of livestock buildings and offering free vaccination programs for exposed livestock.

After the opening of the Trinidad Regional Virus Laboratory in 1953, Arthur Greenhall demonstrated that at least eight species of bats in Trinidad had been infected with rabies; including the common vampire bat, the rare white-winged vampire bat, as well as two abundant species of fruit bats: the Seba's short-tailed bat and the Jamaican fruit bat.[14]

Recent data sequencing suggests recombination events in an American bat led the modern rabies virus to gain the head of a G-protein ectodomain thousands of years ago. This change occurred in an organism that had both rabies and a separate carnivore virus. The recombination resulted in a cross-over that gave rabies a new success rate across hosts since the G-protein ectodomain, which controls binding and pH receptors, was now suited for carnivore hosts as well.[15]

Cryptic rabies refers to unidentified infections, which are mainly traced back to particularly virulent forms in silver-haired and tricolor bats. These are generally rather reclusive species,[16] so the relative degree of infection and similarities between their strains is unusual. Both are independent rabies reservoir species but make up a large number of bites. This absence of typical symptoms can often cause major delays in treatment and diagnosis in both animals and humans, as the required post-exposure prophylaxis and dFAT tests may not be run.

Cats

[edit]In the United States, domestic cats are the most commonly reported rabid animal.[17] In the United States, as of 2008[update], between 200 and 300 cases are reported annually;[18] in 2017, 276 cats with rabies were reported.[19] As of 2010[update], in every year since 1990, reported cases of rabies in cats outnumbered cases of rabies in dogs.[17]

Cats that have not been vaccinated and are allowed access to the outdoors have the most risk for contracting rabies, as they may come in contact with rabid animals. The virus is often passed on during fights between cats or other animals and is transmitted by bites, saliva or through mucous membranes and fresh wounds.[20] The virus can incubate from one day up to over a year before any symptoms begin to show. Symptoms have a rapid onset and can include unusual aggression, restlessness, lethargy, anorexia, weakness, disorientation, paralysis and seizures.[21] Vaccination of felines (including boosters) by a veterinarian is recommended to prevent rabies infection in outdoor cats.[20]

Cattle

[edit]In cattle-raising areas where vampire bats are common, fenced-in cows often become a primary target for the bats (along with horses), due to their easy accessibility compared to wild mammals.[22][23] In Latin America, vampire bats are the primary reservoir of the rabies virus, and in Peru, for instance, researchers have calculated that over 500 cattle per year die of bat-transmitted rabies.[24]

Vampire bats have been extinct in the United States for thousands of years (a situation that may reverse due to climate change, as the range of vampire bats in northern Mexico has recently been creeping northward with warmer weather), thus United States cattle are not currently susceptible to rabies from this vector.[23][25][26] However, cases of rabies in dairy cows in the United States has occurred (perhaps transmitted by bites from canines), leading to concerns that humans consuming unpasteurized dairy products from these cows could be exposed to the virus.[27]

Vaccination programs in Latin America have been effective at protecting cattle from rabies, along with other approaches such as the culling of vampire bat populations.[24][28][29]

Coyotes

[edit]Rabies is common in coyotes, and can be a cause for concern if they interact with humans.[30]

Dogs

[edit]

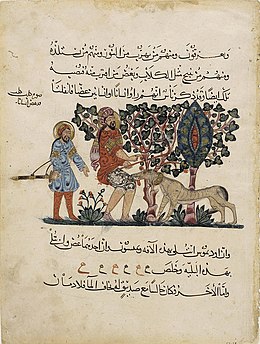

Rabies has a long history of association with dogs. The first written record of rabies is in the Codex of Eshnunna (c. 1930 BC), which dictates that the owner of a dog showing symptoms of rabies should take preventive measure against bites. If a person was bitten by a rabid dog and later died, the owner was fined heavily.[31]

Almost all of the human deaths attributed to rabies are due to rabies transmitted by dogs in countries where dog vaccination programs are not sufficiently developed to stop the spread of the virus.[32]

Foxes

[edit]Rabies is endemic throughout most of the world, though incubation time and antigen types shift depending on its host. Arctic rabies is a specific strain of Rabies lyssavirus that is most closely phylogenetically related to a separate strand halfway down the world in India and has an incubation period that can last up to 6 months, comparable to that of the virus in humans.[33] It is very rarely studied due to difficulties in lab cultivation and in finding samples, but studies have shown unique antigenic variants in different hosts, most commonly the arctic fox, Vulpes lagopus, a highly dense species. Though this strain is claimed to be less pathogenic to humans, that may be a correlation to low exposure rates rather than a physiological fact.

Horses

[edit]Rabies can be contracted in horses if they interact with rabid animals in their pasture, usually through being bitten (e.g. by vampire bats)[25][23] on the muzzle or lower limbs. Signs include aggression, incoordination, head-pressing, circling, lameness, muscle tremors, convulsions, colic and fever.[34] Horses that experience the paralytic form of rabies have difficulty swallowing, and drooping of the lower jaw due to paralysis of the throat and jaw muscles. Incubation of the virus may range from 2–9 weeks.[35] Death often occurs within 4–5 days of infection of the virus.[34] There are no effective treatments for rabies in horses. Veterinarians recommend an initial vaccination as a foal at three months of age, repeated at one year and given an annual booster.[34]

Monkeys

[edit]Monkeys, like humans, can get rabies; however, they do not tend to be a common source of rabies.[36] Monkeys with rabies tend to die more quickly than humans. In one study, 9 of 10 monkeys developed severe symptoms or died within 20 days of infection.[37] Rabies is often a concern for individuals travelling to developing countries as monkeys are the most common source of rabies after dogs in these places.[38]

Rabbits

[edit]Despite natural infection of rabbits being rare, they are particularly vulnerable to the rabies virus; rabbits were used to develop the first rabies vaccine by Louis Pasteur in the 1880s, and continue to be used for rabies diagnostic testing. The virus is often contracted when attacked by other rabid animals and can incubate within a rabbit for up to 2–3 weeks. Symptoms include weakness in limbs, head tremors, low appetite, nasal discharge, and death within 3–4 days. There are currently no vaccines available for rabbits. The National Institutes of Health recommends that rabbits be kept indoors or enclosed in hutches outside that do not allow other animals to come in contact with them.[18]

Red pandas

[edit]Although rare, cases of rabies in red pandas have been recorded.[39]

Skunks

[edit]In the United States, there is currently no USDA-approved vaccine for the strain of rabies that afflicts skunks. When cases are reported of pet skunks biting a human, the animals are frequently killed in order to be tested for rabies. It has been reported that three different variants of rabies exist in striped skunks in the north and south central states.[18]

Humans exposed to the rabies virus must begin post-exposure prophylaxis before the disease can progress to the central nervous system. For this reason, it is necessary to determine whether the animal, in fact, has rabies as quickly as possible. Without a definitive quarantine period in place for skunks, quarantining the animals is not advised as there is no way of knowing how long it may take the animal to show symptoms. Destruction of the skunk is recommended and the brain is then tested for presence of rabies virus.

Skunk owners have recently organized to campaign for USDA approval of both a vaccine and an officially recommended quarantine period for skunks in the United States.[citation needed]

Wolves

[edit]Under normal circumstances, wild wolves are generally timid around humans, though there are several reported circumstances in which wolves have been recorded to act aggressively toward humans.[40] The majority of fatal wolf attacks have historically involved rabies, which was first recorded in wolves in the 13th century. The earliest recorded case of an actual rabid wolf attack comes from Germany in 1557. Though wolves are not reservoirs for the disease, they can catch it from other species. Wolves develop an exceptionally severe aggressive state when infected and can bite numerous people in a single attack. Before a vaccine was developed, bites were almost always fatal. Today, wolf bites can be treated, but the severity of rabid wolf attacks can sometimes result in outright death, or a bite near the head will make the disease act too fast for the treatment to take effect.[40]

Rabid attacks tend to cluster in winter and spring. With the reduction of rabies in Europe and North America, few rabid wolf attacks have been recorded, though some still occur annually in the Middle East. Rabid attacks can be distinguished from predatory attacks by the fact that rabid wolves limit themselves to biting their victims rather than consuming them. Plus, the timespan of predatory attacks can sometimes last for months or years, as opposed to rabid attacks which end usually after a fortnight. Victims of rabid wolves are usually attacked around the head and neck in a sustained manner.[40]

Asian elephants

[edit]One of the largest land mammals on the continent of Asia, these elephants typically live in India, Indonesia, Nepal, and Cambodia: countries that have ongoing rabies epidemics. About 1.4% of these elephants die from rabies, most of these cases come from bites/attacks from wild dogs. When left untreated, the mammal can suffer from Paralytic(dumb) rabies and their limbs slowly begin to paralyze. With that, hunger decreases, bowel movements begin to cease, and the elephant's behavior can begin to change. After 5 days, the animal dies. When treated, elephants receive the 'equine tetanus toxoid' annually. These vaccinated elephants can develop a humoral immune response and combat the deadly symptoms of the rabies virus.[41]

Other placental mammals

[edit]The most commonly infected terrestrial animals in the United States are raccoons, skunks, foxes, and coyotes. Any bites by such wild animals must be considered a possible exposure to the rabies virus.

Most cases of rabies in rodents reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States have been found among groundhogs (woodchucks). Small rodents such as squirrels, hamsters, guinea pigs, gerbils, chipmunks, rats, mice, and lagomorphs like rabbits and hares are almost never found to be infected with rabies, and are not known to transmit rabies to humans.[42]

Outside of the United States, extensive research has been conducted on animals outside the norm of usual infection patterns. The yellow mongoose, native to South Africa, has been known to asymptomatically carry the rabies virus for several years. In a study performed in 1993, several major outbreaks in adjacent farms over the course of 11 years were all traced to a single population.[43] The long-dormant phase of this virus makes horizontal transfer possible in this stage through breeding and typical injuries from territory fights. It is unknown what triggers the emergence of the virus when it does enter the prodromal stage, but it is hypothesized to be caused by stressors such as lack of food or other stressors in heavily populated areas. Complicating this further is the difficulty in testing for rabies before death, as it takes up cells around the brainstem and in the nerves and saliva.

In the same geographic region, the greater kudu, a species of antelope in Namibia, have also suffered enormous outbreaks of rabies in their populations. The greater kudu is a member of the Tragelaphini antelopes, which is more closely related to cows than to other antelopes and is extremely susceptible to the virus. During the first epidemic from 1997 to 1996, as much as 20% of the population succumbed to the disease; phylogenetic analyses likewise proved that the rapid spread was largely by horizontal transfer. Kudu are a large factor in the agriculture and economy of Namibia, but their status as wildlife makes prevention of the disease much more difficult.[44]

Marsupial and monotreme mammals

[edit]The Virginia opossum (a marsupial, unlike the other mammals named above, which are all eutherians/placental), has a lower internal body temperature than the rabies virus prefers and therefore is resistant but not immune to rabies.[45] Marsupials, along with monotremes (platypuses and echidnas), typically have lower body temperatures than similarly sized eutherians.[46]

Birds

[edit]Birds were first artificially infected with rabies in 1884, with work being done on a large variety of species including domestic fowl and pigeons. Hundreds of years of testing has concluded that infected birds are largely, if not wholly, asymptomatic, and recover; a 1988 study examined a number of birds of prey, such as red-tailed hawks, bald eagles, horned owls, and turkey vultures, and concluded that they were unlikely to be reservoirs of rabies.[47] Other bird species have been known to develop rabies antibodies, a sign of infection, after feeding on rabies-infected mammals.[48][49]

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ "CARTER John, SAUNDERS Venetia - Virology : Principles and Applications – Page:175 – 2007 – John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex PO19 8SQ, England – 978-0-470-02386-0 (HB)"

- ^ "Rabies". AnimalsWeCare.com. Archived from the original on 3 September 2014.

- ^ a b Wilson PJ, Rohde RE, Oertli EH, Willoughby Jr RE (2019). Rabies: Clinical Considerations and Exposure Evaluations (1st ed.). Elsevier. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-323-63979-8. Retrieved May 10, 2023.

- ^ "How Do You Know if an Animal Has Rabies? | CDC Rabies and Kids". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Retrieved May 10, 2023.

- ^ "Rabies (for Parents)". KidsHealth.org. Nemours KidsHealth. Retrieved May 10, 2023.

- ^ Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, Abraham J, Adair T, Aggarwal R, et al. (Dec 15, 2012). "Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010" (PDF). Lancet. 380 (9859): 2095–128. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. hdl:10536/DRO/DU:30050819. PMC 10790329. PMID 23245604. S2CID 1541253. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 1, 2020. Retrieved September 27, 2019.

- ^ "Rabies". World Health Organization (WHO). Archived from the original on May 10, 2023. Retrieved May 10, 2023.

- ^ Murray KO, Holmes KC, Hanlon CA (2009-09-15). "Rabies in vaccinated dogs and cats in the United States, 1997–2001". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 235 (6): 691–695. doi:10.2460/javma.235.6.691. PMID 19751164.

- ^ Hueffer K, Khatri S, Rideout S, Harris MB, Papke RL, Stokes C, Schulte MK (2017-10-09). "Rabies virus modifies host behaviour through a snake-toxin like region of its glycoprotein that inhibits neurotransmitter receptors in the CNS". Scientific Reports. 7 (1): 12818. Bibcode:2017NatSR...712818H. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-12726-4. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 5634495. PMID 28993633.

- ^ Ettinger, Stephen J., Feldman, Edward C. (1995). Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine (4th ed.). W.B. Saunders Company. ISBN 978-0-7216-6795-9.

- ^ Goodwin and Greenhall (1961), p. 196

- ^ Pawan (1936), pp. 137-156.

- ^ Pawan, J.L. (1936b). "Rabies in the Vampire Bat of Trinidad with Special Reference to the Clinical Course and the Latency of Infection." Annals of Tropical Medicine and Parasitology. Vol. 30, No. 4. December, 1936.

- ^ Greenhall, Arthur M. 1961. Bats in Agriculture. Ministry of Agriculture, Trinidad and Tobago.

- ^ Ding NZ, Xu DS, Sun YY, He HB, He CQ (2017). "A permanent host shift of rabies virus from Chiroptera to Carnivora associated with recombination". Scientific Reports. 7 (1): 289. Bibcode:2017NatSR...7..289D. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-00395-2. PMC 5428239. PMID 28325933.

- ^ Messenger, Sharon L.; Smith, Jean S.; Rupprecht, Charles E. (15 September 2002). "Emerging Epidemiology of Bat-Associated Cryptic Cases of Rabies in Humans in the United States". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 35 (6): 738–747, https://doi.org/10.1086/342387

- ^ a b Cynthia M. Kahn, ed. (2010). The Merck Veterinary Manual (10th ed.). Kendallville, Indiana: Courier Kendallville, Inc. p. 1193. ISBN 978-0-911910-93-3.

- ^ a b c Lackay SN, Kuang Y, Fu ZF (2008). "Rabies in small animals". Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 38 (4): 851–ix. doi:10.1016/j.cvsm.2008.03.003. PMC 2518964. PMID 18501283.

- ^ "Rabies Vaccination Key to Prevent Infection - Veterinary Medicine at Illinois". University of Illinois College of Veterinary Medicine. Retrieved 2019-12-15.

- ^ a b "Rabies in Cats". WebMD. Retrieved 2016-12-04.

- ^ "Rabies Symptoms in Cats". petMD. Retrieved 2016-12-04.

- ^ Bryner J (2007-08-15). "Thriving on Cattle Blood, Vampire Bats Proliferate". livescience.com. Retrieved 2019-10-28.

- ^ a b c Carey B (2011-08-12). "First U.S. Death by Vampire Bat: Should We Worry?". livescience.com. Retrieved 2019-10-28.

- ^ a b Benavides JA, Paniagua ER, Hampson K, Valderrama W, Streicker DG (2017-12-21). "Quantifying the burden of vampire bat rabies in Peruvian livestock". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 11 (12): e0006105. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0006105. ISSN 1935-2735. PMC 5739383. PMID 29267276.

- ^ a b "Do vampire bats really exist?". USGS. Retrieved 2019-10-28.

- ^ Baggaley K (2017-10-27). "Vampire bats could soon swarm to the United States". Popular Science. Retrieved 2019-10-28.

- ^ "Rabies in a Dairy Cow, Oklahoma | News | Resources | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2019-08-22. Retrieved 2019-10-28.

- ^ Arellano-Sota C (1988-12-01). "Vampire bat-transmitted rabies in cattle". Reviews of Infectious Diseases. 10 (Suppl 4): S707–709. doi:10.1093/clinids/10.supplement_4.s707. ISSN 0162-0886. PMID 3206085.

- ^ Thompson RD, Mitchell GC, Burns RJ (1972-09-01). "Vampire bat control by systemic treatment of livestock with an anticoagulant". Science. 177 (4051): 806–808. Bibcode:1972Sci...177..806T. doi:10.1126/science.177.4051.806. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 5068491. S2CID 45084731.

- ^ Wang X, Brown CM, Smole S, Werner BG, Han L, Farris M, DeMaria A (2010). "Aggression and Rabid Coyotes, Massachusetts, USA". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 16 (2): 357–359. doi:10.3201/eid1602.090731. PMC 2958004. PMID 20113587.

- ^ Dunlop RH, Williams, David J. (1996). Veterinary Medicine:An Illustrated History. Mosby. ISBN 978-0-8016-3209-9.

- ^ "Rabies and Your Pet". American Veterinary Medical Association. Retrieved 2019-12-15.

- ^ Mørk T, Prestrud P (2004-03-31). "Arctic Rabies – A Review". Acta Veterinaria Scandinavica. 45 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1186/1751-0147-45-1. ISSN 1751-0147. PMC 1820997. PMID 15535081.

- ^ a b c "Rabies and Horses". www.omafra.gov.on.ca. Retrieved 2016-12-04.

- ^ "Rabies in Horses: Brain, Spinal Cord, and Nerve Disorders of Horses: The Merck Manual for Pet Health". www.merckvetmanual.com. Archived from the original on 2016-11-13. Retrieved 2016-12-04.

- ^ "Diseases Transmissible From Monkeys To Man - Monkey to Human Bites And Exposure". www.2ndchance.info. Retrieved 2016-12-04.

- ^ Weinmann E, Majer M, Hilfenhaus J (1979). "Intramuscular and/or Intralumbar Postexposure Treatment of Rabies Virus-Infected Cynomolgus Monkeys with Human Interferon". Infection and Immunity. 24 (1). American Society for Microbiology: 24–31. doi:10.1128/IAI.24.1.24-31.1979. PMC 414256. PMID 110693.

- ^ Di Quinzio M, McCarthy A (2008-02-26). "Rabies risk among travellers". CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal. 178 (5): 567. doi:10.1503/cmaj.071443. ISSN 0820-3946. PMC 2244672. PMID 18299544.

- ^ "How to Care for Red Pandas". Smithsonian's National Zoo. 2020-09-22. Retrieved 2023-08-10.

- ^ a b c "The Fear of Wolves: A Review of Wolf Attacks on Humans" (PDF). Norsk Institutt for Naturforskning. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2005-02-11. Retrieved 2008-06-26.

- ^ Isaza R, et al. (November 2006). "Results of Vaccination of Asian Elephants (Elephas Maximus) With Monovalent Inactivated Rabies Vaccine". American Journal of Veterinary Research. 67 (11): 1934–1936. doi:10.2460/ajvr.67.11.1934.

- ^ "Rabies. Other Wild Animals: Terrestrial carnivores: raccoons, skunks and foxes". 1600 Clifton Rd, Atlanta, GA 30333, USA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 2010-12-23.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Taylor PJ (December 1993). "A systematic and population genetic approach to the rabies problem in the yellow mongoose (Cynictis penicillata)". The Onderstepoort Journal of Veterinary Research. 60 (4): 379–387. ISSN 0030-2465. PMID 7777324.

- ^ Hikufe EH, Freuling CM, Athingo R, Shilongo A, Ndevaetela EE, Helao M, Shiindi M, Hassel R, Bishi A, Khaiseb S, Kabajani J, Westhuizen Jv, Torres G, Britton A, Letshwenyo M (2019-04-16). "Ecology and epidemiology of rabies in humans, domestic animals and wildlife in Namibia, 2011-2017". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 13 (4): e0007355. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0007355. ISSN 1935-2735. PMC 6486109. PMID 30990805.

- ^ McRuer DL, Jones KD (May 2009). "Behavioral and nutritional aspects of the Virginian opossum (Didelphis virginiana)". The Veterinary Clinics of North America. Exotic Animal Practice. 12 (2): 217–36, viii. doi:10.1016/j.cvex.2009.01.007. PMID 19341950.

- ^ Gaughan, John B., Hogan, Lindsay A., Wallage, Andrea (2015). Abstract: Thermoregulation in marsupials and monotremes, chapter of Marsupials and monotremes: nature's enigmatic mammals. Nova Science Publishers, Incorporated. ISBN 978-1-63483-487-2. Retrieved 2022-04-20.

- ^ Shannon LM, Poulton JL, Emmons RW, Woodie JD, Fowler ME (April 1988). "Serological survey for rabies antibodies in raptors from California". Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 24 (2): 264–7. doi:10.7589/0090-3558-24.2.264. PMID 3286906.

- ^ Gough PM, Jorgenson RD (July 1976). "Rabies antibodies in sera of wild birds". Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 12 (3): 392–5. doi:10.7589/0090-3558-12.3.392. PMID 16498885. S2CID 27867384.

- ^ Jorgenson RD, Gough PM, Graham DL (July 1976). "Experimental rabies in a great horned owl". Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 12 (3): 444–7. doi:10.7589/0090-3558-12.3.444. PMID 16498892. S2CID 11374356.

References

[edit]- Baynard, Ashley C. et al. (2011). "Bats and Lyssaviruses." In: Advances in VIRUS RESEARCH VOLUME 79. Research Advances in Rabies. Edited by Alan C. Jackson. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-12-387040-7.

- Goodwin G. G., and A. M. Greenhall. 1961. "A review of the bats of Trinidad and Tobago." Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, 122.

- Joseph Lennox Pawan (1936). "Transmission of the Paralytic Rabies in Trinidad of the Vampire Bat: Desmodus rotundus murinus Wagner, 1840." Annual Tropical Medicine and Parasitol, 30, April 8, 1936, pp. 137–156.