R. L. Burnside

R. L. Burnside | |

|---|---|

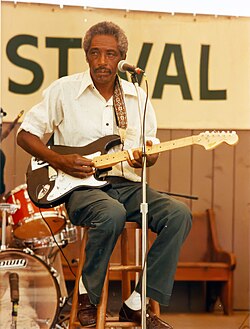

Burnside performing at the 1982 World's Fair in Knoxville, Tennessee | |

| Background information | |

| Born | November 23, 1926 Harmontown, Mississippi, U.S. |

| Origin | Oxford, Mississippi, U.S. |

| Died | September 1, 2005 (aged 78) Memphis, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Genres | |

| Instruments |

|

| Years active | 1960s–2005 |

| Labels | Fat Possum |

R. L. Burnside (November 23, 1926 – September 1, 2005) was an American blues singer, songwriter and guitarist. He played music for much of his life but received little recognition before the early 1990s. In the latter half of that decade, Burnside recorded and toured with Jon Spencer, garnering crossover appeal and introducing his music to a new fan base in the punk and garage rock scenes.

Life and career

[edit]1926–1959: Early years

[edit]Burnside was born in 1926[1] to Earnest Burnside and Josie Malone,[2] in either Harmontown,[3] College Hill,[4][5] or Blackwater Creek,[6] all of which are in the rural part of Lafayette County, Mississippi, near the area that would be covered by Sardis Lake a few years later. His first name is given variously as R. L.,[7] Rural,[8][7][n 1] Robert Lee,[6] Rule,[7] or Ruel. His father left the family early on, and R. L. grew up with his mother, grandparents, and several siblings.

He played the harmonica and dabbled with playing guitar, beginning at the age of 16. He said he first played in public at age 21 or 22.[9][10] He learned mostly from Mississippi Fred McDowell, who had lived near Burnside since Burnside was a child. He first heard McDowell playing at age 7 or 8[11] and eventually joined his gigs to play a late set.[10][12] Other local teachers were his wife's brother,[9] his uncle-in-law Ranie Burnette,[11] who was a popular player from Senatobia,[13] the mostly unknown Henry Harden,[14] Son Hibbler, Jesse Vortis, and possibly Stonewall Mays.[15] Burnside cited church singing[12][16] and fife-and-drum picnics as elements of his childhood's musical landscape, and he credited Muddy Waters, Lightnin' Hopkins, and John Lee Hooker as influences in adulthood.[9][10][11]

In the late 1940s[17] he moved to Chicago, where his father had lived since he separated from his mother,[10] in the hope of finding better economic opportunities.[10] He found jobs at metal and glass factories,[11][18][19] had the company of Muddy Waters (his cousin-in-law),[10] and enjoyed the blues scene on Maxwell Street.[2][17] But things did not turn out as he had hoped; within the span of one year his father, two brothers, and two uncles were all murdered in the city.[12][n 2]

Three years after coming to Chicago,[12][17] Burnside went back south. He married Alice Mae Taylor in 1949 or 1950,[20][21][19] his second marriage.[9][n 3] He moved several times in the 1950s, between Memphis, Tennessee, the Mississippi Delta and the hill country of northern Mississippi.[22][8][23] During his time in the Delta, he met bluesmen Robert Lockwood Jr. and Aleck "Rice" Miller.[9][10] It seems it was around that time that Burnside killed a man, possibly at a craps game, was convicted of murder and incarcerated in Parchman Farm.[21][24] He would later relate that his boss at the time had arranged to release him after six months, as he needed Burnside's skills as a tractor driver.[n 4]

1960–1990: Part-time musician

[edit]He spent the next 45 years, not unlike his early years, in Panola and Tate counties, in northern Mississippi. At first he kept to particularly remote dwellings,[20] working into the 1980s as a sharecropper growing cotton and soybean, as a commercial fisherman on the Tallahatchie River, selling his catch from door to door,[9][26] and as a truck driver.[27] Later he moved closer to Holly Springs. After coming back to Mississippi, and especially after marrying,[14] he picked more local gigs,[17] playing guitar in juke joints and bars[3] (some under his management),[2][11][8][28] at picnics and at his own open house parties,[23][n 5] and at the occasional festival.

His earliest recordings were made in 1967 by George Mitchell, then a graduate student of journalism. Mitchell and his wife went on a 13-day summer trip in Mississippi, which resulted in the first recordings of several country blues artists.[29] He came to Burnside's house near Coldwater on the advice of fife player and maker Othar Turner.[30] Mitchell wrote that Fred McDowell had not told him about Burnside, likely because Burnside posed "big-time competition".[31] Six of the songs, played on an acoustic guitar lent by Mitchell, were released on Arhoolie Records after two years; nine others are on later records. Another album of acoustic material was recorded in 1969 for Adelphi Records, not to be released until thirty years later. Recordings from 1975 had a similar fate.[32][33]

These recordings featured Burnside playing acoustic guitar and singing, and a few tracks had harmonica accompaniment by W.C. Veasey or Ulysse Red Ramsey. Although not recorded, by that time Burnside also played electric guitar.[8][23] His early repertoire came from hill country and Memphis favorites, John Lee Hooker, Muddy Waters,[34] hits by Howlin' Wolf and Elmore James, and sides by Yank Rachell, Lightnin' Hopkins, and Lonesome Sundown.

In 1969 he performed for the first time outside the United States, at a program in Montreal with Lightnin' Hopkins and John Lee Hooker.[9][10] As a solo performer, he made three tours in Europe, appearing before enthusiastic audiences.[23] In 1974 he played at the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival, the first of nine of these festivals at which he performed.[35] Also in 1974, Tav Falco filmed Burnside in the Brotherhood Sportsmen's Lodge, a juke joint he ran at the time near Como.[36][37][n 6] His performance featured the slide guitarist Kenny Brown, Burnside's friend and understudy, whom he began tutoring in 1971 and claimed as his "adopted son".[41][42] In 1978 Burnside was filmed by Alan Lomax in what remained mostly outtakes of the television documentary The Land Where the Blues Began.[n 7]

A series of recordings in 1979 by the musicologist David Evans for his record label High Water was the first to feature Burnside's Sound Machine, which included his sons Duwayne and Daniel on guitar, his son Joseph on bass, and his son-in-law Calvin Jackson on drums.[20] The band was active mostly in home settings but also joined Burnside in Europe in 1980[23] and 1983. They offered a rare fusion of rural and urban blues, funk, R&B and soul,[8][n 8] which appealed to young Mississippians;[23] their sets included covers of songs by Jimmy Rogers, Little Walter, Albert King and Little Milton. An EP, Sound Machine Groove, was released by Evans's label in the US but had next to no distribution.[43][44] Apart from it, one full album of the same title, a debut of sorts, was licensed for prompt European release by Disques Vogue,[23] and another hour's worth was released by the Memphis label Inside Sounds in 2001.[45]

From 1980 to 1986, Burnside recorded for the Dutch label Old Swingmaster and for the French label Arion, mostly solo or with harmonica accompaniment: Johnny Woods served on some occasions (he also recorded as a lead artist, with guitar accompaniment by Burnside); Curtis Salgado served once in a New Orleans session. Selections focused on hill country material and starker, less danceable songs by Lightnin' Hopkins, Muddy Waters and John Lee Hooker. The results were four more LP releases and a videotape under his name, all in European markets.[46][47]

In the mid-1980s Burnside retired from farm work and became more busy with the music.[17] For about 12 years he worked with New Orleans–based harpist Jon (Joni) Morris Neremberg (or Nuremberg).[9][20][8] He appeared before American crowds at such occasions as the 1982 World's Fair, the 1984 Louisiana World Exposition,[20] and the 1986 San Francisco Blues Festival,[48] between international tours.[20][49] By the mid-1980s he toured about "once a year or maybe twice",[17] and by one report in 1985 he had been to Europe 17 times.[9] Recordings from his time with Morris were eventually released on two records, both produced by M.C. Records and Louis X. Erlanger: Acoustic Stories (a session from 1988) and Well, Well, Well (a 2001 compilation of informal recordings provided by Morris).[11]

1991–2005: Commercial success and declining health

[edit]

In the late 1970s or early 1980s, Burnside was introduced and struck a partnership with Junior Kimbrough.[17] Roughly a decade later, his own Burnside Palace had shut down[28][n 9] and the family lived next to the Kimbroughs' new Junior's Place in Chulahoma, Mississippi and collaborated with the counterpart musical family.[11][43][51] The music writer Robert Palmer, teaching for a time in the University of Mississippi in Oxford, frequented the scene with some celebrity musicians, which led to the making in 1990 of the documentary Deep Blues, in which Burnside was prominently featured.

Burnside began recording for the Oxford, Mississippi, label Fat Possum Records in 1991.[1] The label, dedicated to recording aging north Mississippi bluesmen such as Burnside and Junior Kimbrough,[21][52] was founded by two students who had been attending their performances for some years[53][54]—Peter Redvers-Lee, editor of Living Blues magazine, and Matthew Johnson, a writer for the magazine. Burnside remained with Fat Possum from that time until his death. Their first output was Bad Luck City (1992), featuring the Sound Machine. The next, Too Bad Jim (1994), was recorded at Junior's Place and produced by Palmer, with support from Calvin Jackson and Kenny Brown.[51][55] After Jackson moved to Holland,[41][42] Burnside found a new stable band and would usually perform with Brown and drummer Cedric Burnside, his grandson. R.L. played his first art museum gig when Grammy nominee/producer Larry Hoffman brought him to Baltimore to play the Walters Art Museum in February, 1993 as the feature of a Baltimore Folk Music Society concert.

In a New York concert around the release of the documentary Deep Blues, he attracted the attention of Jon Spencer, the leader of the Jon Spencer Blues Explosion.[56] He started touring with this group in 1995, both as an opening act and sitting in,[56] gaining many new fans.[57] The 1996 album A Ass Pocket of Whiskey was recorded with Spencer's band and was marketed for their audience, but was credited to Burnside.[56] It gained critical acclaim and received praise from Bono and Iggy Pop; Billboard magazine wrote that "it sounds like no other blues album ever released"[56] and an author there picked it for a year's end critics' poll,[58] but Living Blues opined that it was "perhaps the worst blues album ever made."[59][n 10]

After parting ways with the Blues Explosion, the label turned to produce music in which recorded materials were remixed by producer Tom Rothrock with an eye to techno, downtempo and hip-hop listeners. The experiment started with a track in Mr. Wizard (1997),[60][61] an album based on a variety of sessions, and matured into a full album with Come On In (1998).[62] The recording artists themselves heard only the final product, but they conceded that with time they came to like it, in part influenced by its popularity.[41][63]

Burnside continued to tour, perhaps more extensively than ever. He opened for the Beastie Boys,[11][64] was a musical guest on Late Night with Conan O'Brien and on HBO's Reverb, provided entertainment at private events such as Richard Gere's birthday party,[21] and participated in shared or showcase bills with other Fat Possum artists, notably T-Model Ford, Paul "Wine" Jones, CeDell Davis, Robert Cage and Robert Belfour. An influx of visitors and young musicians were attracted to Junior's Place, before it burned down in 2000.

Documentary coverage of his contemporaneous life and work expanded too. Bradley Beesley filmed the 60-minute Hill Stomp Hollar, a film about Burnside and other Fat Possum artists, that received a positive response[65] at the 1999 SXSW Film Festival premiere,[66] but that was not approved for release by the label.[67] Much of Beesley's footage and many of his interviews became part of the 77-minute You See Me Laughin', directed by Mandy Stein; it was released by Fat Possum in 2003. A 1999 date at Paris' New Morning club, with Brown and Cedric, was an occasion at which the French blues singer Sophie Kay (also known as Sophie Kertesz) filmed a 52-minute documentary.

Before long, however, Burnside was in declining health. He had an ear infection and underwent heart surgery in 1999.[3][68][69][70] As his tours decreased to a minimum,[71][72] Wish I Was In Heaven Sitting Down (2000) was released, which relegated guitar work to other players (Rick Holmstrom, Smokey Hormel, John Porter) but used Burnside's vocals.[11][73] After a heart attack in 2001, his doctor advised him to stop drinking; Burnside did, but he reported that change left him unable to play.[25] Fat Possum rebounded with A Bothered Mind (2004), an album that used previously recorded guitar tracks, and included collaborations with Kid Rock and Lyrics Born.[74]

These remix albums received mixed reviews, some describing the results as "unnatural"[75] while others lauded the playful spirit,[76] or "the way it yokes authentic blues feeling to new technology".[77] Commercially, the remixes were successful; each surpassed its previous in Billboard's Top Blues Albums chart, as they stayed there for 12–18 weeks' periods (but none entered into the more competitive Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs),[78][n 11] and two tracks from Come On In were included in The Sopranos' soundtrack. "Let My Baby Ride" off Come On In received significant airplay and an ensuing music clip was slotted in MTV's 120 Minutes;[63] the album's "Rollin' & Tumblin'" accompanied a 2002 Nissan TV commercial.[11][82][83] But the live, unremixed album Burnside on Burnside (2001) peaked at number 4 of Billboard's Blues Albums chart[78] and was nominated for a Grammy.[84] – the last article to catch Burnside as an active bandleader, recorded in January 2001 with Brown and Cedric.

In between, Fat Possum licensed and released First Recording (2003), comprising George Mitchell's 1967 recordings in its fullest edition yet, in traditional format.[n 12] In addition, the 1990s and 2000s saw release of several recordings from previous decades by other labels (see above), as well as a couple of new recordings by HighTone Records.

Death and legacy

[edit]Another heart attack in November 2002 resulted in a surgery in 2003, and short-circuited any future career plans he had.[11][68] Yet Burnside continued as guest singer on occasions, such as at Bonnaroo Music Festival, 2004, his last public appearance.[86] He died at St. Francis Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee, on September 1, 2005, at the age of 78.[87] Services were held at Rust College, in Holly Springs, with burial in the Free Springs Cemetery, in Harmontown. Around the time of his death, he resided in Byhalia, Mississippi. His immediate survivors included:[87]

- His wife: Alice Mae Taylor Burnside (1932–2008),[88] married 1949[19][21]

- His daughters: Mildred Jean Burnside (1949–2010),[89] Linda Jackson, Brenda Kay Brooks, and Pamela Denise Burnside

- His sons: Melvin Burnside, R.L. Burnside Jr. (1954–2010),[90] Calvin Burnside, Joseph Burnside, Daniel Burnside, Duwayne Burnside, Dexter Burnside, Garry Burnside, and Rodger Harmon

- His sisters: Lucille Burnside, Verlyn Burnside, and Mat Burnside

- His brother: Jesse Monia

- His 35 grandchildren: Cedric Burnside

- 32 great-grandchildren

Members of his extended family continue to play blues in the Holly Springs area and in wider circles:

- His son Duwayne Burnside has played guitar with the North Mississippi Allstars (Polaris; Hill Country Revue with R. L. Burnside). He has operated music venues named after Burnside and Alice Mae in Chulahoma, Memphis,[91][92] Waterford,[93] and Holly Springs[94]

- His grandson Cedric Burnside has released six albums with four musical partners and toured with Kenny Brown and others

- His son Garry Burnside used to play bass guitar with Junior Kimbrough, North Mississippi Allstars, and Hill Country Revue; in 2006 he released an album with Cedric

- His son-in-law Calvin Jackson recorded with blues musicians of Burnside's generation and younger

- His grandson Kent Burnside is also a touring blues musician. Kent is currently touring with the Flood Brothers and released an album with them in 2016[95]

- His grandson Cody released four albums and toured with the family and his own band

Burnside won one W. C. Handy Award in 2000 (Traditional Blues Male Artist of the Year),[96] two in 2002 (Traditional Blues Male Artist of the Year; Traditional Blues Album of the Year, Burnside on Burnside),[97][98] and one in 2003 (Traditional Blues Male Artist of The Year);[99] he had 11 unsuccessful nominations in 8 years for the awards, starting in 1982,[100] as well as one for a Grammy. Several of the Mississippi Blues Trail markers, which have been erected since 2006, mention him. In 2014 he was inducted to the Blues Hall of Fame in Memphis.[101]

Burnside's fellow Fat Possum musicians The Black Keys credit him as an influence and interpolated his "Skinny Woman" into their track "Busted".[citation needed]The Black Keys would perform two Burnside covers on their album Delta Kream in 2021 featuring Kenny Brown. Brown along with bassist Eric Deaton would also join The Black Keys for their 2022 tour (supporting the release of Dropout Boogie) to perform the Burnside covers live.

The electronica musician St. Germain used samples of Burnside's "Nightmare Blues" throughout the track "How Dare You", on his 2015 album.[102]

Style

[edit]

Burnside had a powerful, expressive voice, that did not fail with old age but rather grew richer,[11][21] and played both electric and acoustic guitar, with and without a slide. His drone-heavy style was more characteristic of North Mississippi hill country blues than Delta blues. Like other country blues musicians, he did not always adhere to strict 12- or 16-bar blues patterns, often adding extra beats to a measure as he saw fit.[103] His rhythms are often based on the fife and drum blues of north Mississippi.[55][104][n 13]

As was the case with his role model John Lee Hooker, Burnside's earliest recordings sound quite similar to one another, even repetitive, in vocal and instrumental styling. Many of these songs eschew traditional chord changes in favor of a single chord[8][30][55] or a simple bassline pattern that repeats throughout. Burnside played the guitar fingerstyle—without a pick—and often in open-G tuning.[34] His vocal style is characterized by a tendency to "break" briefly into falsetto, usually at the end of long notes.

Like his contemporary T-Model Ford, Burnside favored a stripped-down approach to the blues, marked by a quality of rawness. He and his later managers and reviewers maintained his persona as a hard-working man leading a life of struggle,[105] a heavy drinker, latent criminal singing songs of swagger and rebellion.

Burnside knew many toasts—African American narrative folk poems such as "Signifying monkey" and "Tojo Told Hitler"—and fondly recited them between songs at his concerts and on recordings. He narrated long jokes in concerts and social events,[57][106] and many sources noted his quick wit and charisma.

Discography

[edit]Studio albums

[edit]- Sound Machine Groove (1981)

- Plays and Sings the Mississippi Delta Blues (1981)

- Mississippi Hill Country Blues (1987)

- Skinny Woman (1989)

- Bad Luck City (1992)

- Too Bad Jim (1994)

- A Ass Pocket of Whiskey (1996)

- Mr. Wizard (1997)

- Acoustic Stories (1997)

- Come On In (1998)

- Wish I Was in Heaven Sitting Down (2000)

- A Bothered Mind (2004)

Live albums

[edit]- Mississippi Blues (1984)

- Burnside on Burnside (2001)

Compilation albums

[edit]- Going Down South (1999)

- My Black Name a-Ringin' (1999)

- Well, Well, Well (2001)

- Raw Electric (2002)

- No Monkeys on this Train (2003)

- First Recordings (2003)

- Rollin' and Tumblin': the King of Hill Country Blues (2010)

- Long Distance Call (2019)

Films

[edit]- Honky Tonk (1974), by Tav Falco

- The Land Where the Blues Began (1979) by Alan Lomax, John Melville Bishop, and Worth Long in association with the Mississippi Authority for Educational Television

- American Patchwork: Songs and Stories of America, part 3: "The Land Where the Blues Began" (1990), North Carolina Public TV, a lightly re-edited version of "The Land Where the Blues Began" (1979)

- The Land Where the Blues Began (2010), restored original version, DVD containing two additional performances by Burnside

- Deep Blues: A Musical Pilgrimage to the Crossroads (1991), directed by Robert Mugge

- Hill Stomp Hollar (1999), by Bradley Beesley

- Un jour avec... R. L. Burnside (1999/2001), by Sophie Kertesz, produced and distributed by Ciné-Rock, Paris OCLC 691729826

- You See Me Laughin': The Last of the Hill Country Bluesmen (2002), released by Fat Possum Records in 2005, produced and directed by Mandy Stein, Oxford, Mississippi: Plain Jane Productions, Fat Possum Records

- Richard Johnston: Hill Country Troubadour (2005), directed by Max Shores, Alabama PBS, featuring an interview with Burnside and information about the Holly Springs music community

- Big Bad Love (2001), directed by Arliss Howard, with soundtrack songs by Burnside and a cameo live performance, MGM/IFC Films

- Holy Motors (2012), directed by Leos Carax, with an accordion and drum cover of "Let My Baby Ride" by Docteur L

Further reading

[edit]- Dessier, Matthieu (2006). The Real Deal: Experiencing Authenticity in the Music of R.L. Burnside. M.A. thesis. University of Mississippi. OCLC 82143665

- Smirnoff, Marc, ed. (2008). The Oxford American Book of Great Music Writing. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Burnside's headstone reads "R. L. (Rural) Burnside".

- ^ Burnside would later draw upon this experience in his work, particularly in his interpretation of Skip James's "Hard Time Killing Floor" and the talking blues "R.L.'s Story", the opening and closing tracks of Wish I Was in Heaven Sitting Down (2000).

- ^ His first marriage is apparently alluded to in a story he would tell in response to questions like "What is the blues about?": "It's when you get to your house, late at night, and the first thing you meet out there in the driveway is the cat, sayin'—[in a well-imitated cat's voice] 'She-ain't-here, She-ain't-here.'—You got the blues then. Your wife done gone." (Cited from "New York Magazine". Newyorkmetro.com: 94. 11 September 1995. ISSN 0028-7369.; similar versions of the story are in "Have You Ever Been Lonely" from A Ass Pocket of Whiskey (1996) and the opening of You See Me Laughin')

- ^ About the incident he would recite, "I didn't mean to kill nobody. I just meant to shoot the sonofabitch in the head and two times in the chest. Him dying was between him and the Lord."[25]

- ^ Evans provided a few more details: Nelson, Chris (1997-08-02). "Classic R.L. Burnside 'House Party' Style Recordings Reissued". MTV News. Archived from the original on June 21, 2015. Retrieved 2015-06-17., to which the Mississippi Blues Commission adds at: "Tate County Blues". Mississippi Blues Trail.

- ^ Some of the 26 minutes of footage is included in You See Me Laughin'. Burnside was instrumental in Falco becoming a guitarist,[38] and Tav Falco's Panther Burns were probably the first to cover, and name, a Burnside composition on record: "Snake Drive" on Behind the Magnolia Curtain, 1981.[39][40] Band member Lorette Velvette produced other early covers in her solo albums.

- ^ Later released on a 2010 DVD, and the Alan Lomax Archive's Youtube channel: playlist

- ^ In Burnside's words, "they can play rock 'n' roll and disco too".[9]

- ^ Like many joints that were abandoned in response to the crack epidemic.[11][50]

- ^ His work with Jon Spencer was later cited as an influence by Hillstomp[1] and covered on record by The Immortal Lee County Killers.[citation needed]

- ^ From a hip-hop perspective the Fat Possum efforts were among the very first to incorporate the blues, but ultimately did not alter the younger genre's landscape.[79] One clear precursor is found in The Wolf that House Built from Little Axe,[80] others are by Chris Thomas (King). Contemporary projects, that used archival blues samples, included Moby's extremely successful Play (1999), Tangle Eye's remix of Alan Lomax material (2004), and with a broader mix, Alabama 3's Exile on Coldharbour Lane (1997).[81]

- ^ In interviews Watson and Johnson of Fat Possum have indicated that Burnside was the label's best seller and enabled them to finance less commercially-assured projects, and sign new artists.[25][52][28][85]

- ^ Compare Burnside's vocal imitation of fife and drum music: You See Me Laughin' (see filmography), min. 25:55ff.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Skelly, Richard. "R.L. Burnside". AllMusic. Retrieved December 30, 2011.

- ^ a b c Bruin, Leo (1981). Liner notes, R. L. Burnside Plays and Sings the Mississippi Delta Blues. scan

- ^ a b c "Blues Veteran R.L. Burnside Dies". Billboard.com. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- ^ Miller, David Michael. Birthplaces of Mississippi Blues Artists (Map).

- ^ "Oxford Blues". Mississippi Blues Trail.

- ^ a b Eagle, Bob L.; LeBlanc, Eric S. (2013). Blues: A Regional Experience. ABC-CLIO. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-313-34424-4.

- ^ a b c Scott Barretta. "Burnside, R. L." The Mississippi Encyclopedia. Ted Ownby and Charles Reagan Wilson, eds. University Press of Mississippi, 2017. p. 155. ISBN 9781496811592 "His given name appears to have been R. L.; his friends often called him Rule or Rural."

- ^ a b c d e f g Gérard Herzhaft (1992). "R. L Burnside". Encyclopedia of the Blues (second ed.). University of Arkansas Press. pp. 28–29. ISBN 978-1-61075-139-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j [Jeff Hannusch] (August 1985). Connie Atkinson (ed.). "A Bluesman Lives the Life [interview]". Wavelength: New Orleans Music Magazine. No. 58. Nauman S. Scott. pp. 23–24.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Mabe, Ed (November 1999). "R. L. Burnside: One Badass Bluesman: Interview and Photos". Perfect Sound Forever.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m John Puckett (December 2004). "R.L. Burnside: North Mississippi Blues Legend". Vintage Guitar. Retrieved 2015-04-30.

- ^ a b c d Filmed interview. You See Me Laughin' (see filmography), minutes 25–30.

- ^ Evans, David (1978), Afro-American Folk Music from Tate and Panola Counties, Mississippi (PDF), Archive of Folk Song, Library of Congress, p. 16

- ^ a b Bruin, Leo, and Laundre, Kent. Liner notes of Mississippi Hill Country Blues. Swingmaster CD 2201. scan 1, scan 2

- ^ According to Axel Küstner, who met them both in 1978: Liner notes to 'Mississippi Delta Blues', 1982: discogs, scan.

- ^ Nelson, Chris (2000-12-08). "The Story Behind R.L. Burnside's Sad 'Story'". MTV News. Archived from the original on June 23, 2015. Retrieved 2015-06-22.

- ^ a b c d e f g Stiles, Ray M. (1998-08-01). "Interview with R.L. Burnside & Kenny Brown". Blues on Stage.

- ^ Leigh, Spencer (2005-09-03). "R. L. Burnside". Obituaries. The Independent. Retrieved 2011-10-20.

- ^ a b c "R. L. Burnside". Contemporary Black Biography. Gale Group. 2006. Retrieved 2015-05-23.

- ^ a b c d e f Sylvester Oliver (2005-09-29). "A memoriam to bluesman R.L. Burnside". The South Reporter: Part 1; Part 2.

- ^ a b c d e f McInerney, Jay. "White Man at the Door: One Man's Mission to Record the 'Dirty Blues' – before Everyone Dies." New Yorker (February 4, 2002), page 55.

- ^ "R.L.'s Story", interview clip from Wish I Was in Heaven Sitting Down (2000)

- ^ a b c d e f g Evans, David (1980). Notes to High Water 410 EP (scan), and to Sound Machine Groove, 1981/1997 (scan).

- ^ "Parchman Farm". Mississippi Blues Trail.

- ^ a b c Grant, Richard (2003-11-16). "Delta Force". Observer Music Monthly. Retrieved 2010-02-26.

- ^ "Charleston interview", audio clip, recorded May 1986), in Well, Well, Well (2001)

- ^ Fortunato, John (1998). "R.L. Burnside Welcomes All to 'Come On In'". beermelodies. Retrieved 2015-07-09.

- ^ a b c Rubin, Mike (May 1997). "Call of the Wild". Spin. pp. 74–82, 128–131. ISSN 0886-3032.

- ^ Stephen McDill (August 16, 2013). "Summer of Blues: Thirteen Days in the Hill Country". Mississippi Business Journal. Archived from the original on June 29, 2015. Retrieved 2015-06-13.

- ^ a b George Mitchell; David Evans. Arhoolie 1042 (1969) liner notes (scans: 1, 2)

- ^ Booklet of The George Mitchell Collection (2007), FP 1114. Quoted in Jeff Harris (2008-03-23). "A Look At The George Mitchell Collection - Part 2". Big Road Blues. Retrieved 2015-06-03.

- ^ Wolf LP 120.917 leaflet (scan)

- ^ "The King Of Hill Country Blues: Rollin' & Tumblin'". Discogs.com. 2010.

- ^ a b Arhoolie 1042 (1969) leaflet (scan)

- ^ New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Archive – performers list. See also 1975 setlist

- ^ Morse, Erik. "Bomb — Artists in Conversation: Tav Falco". Bomb. Retrieved 2015-06-07.

- ^ "Tav Falco Panther Burns: Films and Videos". 7 December 2014.

- ^ Richard A. Pleuger (May 2006). "Inside the Invisible Empire: My Travels with Rock 'n' Roll Legend Tav Falco and His Unapproachable Panther Burns". Arthur Magazine (21). Retrieved 2015-06-12.

- ^ Wallace Lester, Wallace. "Record Of The Issue - Tav Falco's "Behind The Magnolia Curtain"". The Local Voice. No. 159. Oxford, Mississippi. Retrieved 2015-06-12.

- ^ "R.L. Burnside | Credits". AllMusic. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- ^ a b c Michael Koster; Carter Grice (Summer 1999). "Kenny Brown – America's Finest Slide Guitar Player? [interview]". Thirsty Ear Magazine. Archived from the original on 2013-09-09.

- ^ a b Cedric Burnside and Kenny Brown. Interview. Jefferson Blues Magazine, Issue 141, March 2004. Swedish original Archived 2017-06-30 at the Wayback Machine, via Google Translate

- ^ a b James Lien (November 1998). "Mississippi Juke Joints". CMJ New Music Monthly.

- ^ "New Blues Label Founded at Memphis State Univ". Billboard. 6 September 1980. p. 8. ISSN 0006-2510.

- ^ "Raw Electric: 1979–1980". Discogs.com. 2001.

- ^ Jean-Pierre Urbain. "CD Review: R.L.BURNSIDE on SWINGMASTER". Retrieved 2016-03-21 – via Google Groups.

- ^ "R.L. Burnside With Johnny Woods – Live 1984 / 1986". Discogs.com. 2008.

Part 2 was filmed in Swingmaster's record shop, Groningen (The Netherlands) in 1984 and was previously issued as a video by Swingmaster.

- ^ "1986 Archives". San Francisco Blues Festival.

- ^ Vanna Pescatori (1990-11-04). "Cuneo, il sound di Burnside e Morris". La Stampa Cuneo (in Italian). p. 7. Retrieved 2015-06-27.

- ^ Allison Stewart (2002-12-06). "Vintage T-Model Ford is the real deal". Chicago Tribune.

- ^ a b Sinclair, John (1993). "Robert Palmer: Site-Specific Music [interview]". Johnsinclair.us. Archived from the original on June 26, 2015. Retrieved June 24, 2015.

- ^ a b Gill, Andy (24 June 2005). "We've Still Got the Blues". The Independent. Archived from the original on July 22, 2015. Retrieved 2014-01-23.

- ^ Morris, Chris (11 June 1994). "Mississippi Labels Tap into Wealth of Delta Blues Talent". Billboard. Nielsen Business Media. pp. 1, 95. ISSN 0006-2510.

- ^ Dixon, Michael (Winter 1997). "Fat Possum: A Rocky Road for the Roots Label". Blues Access. Retrieved 2014-07-30.

- ^ a b c Robert Palmer. Liner notes to Too Bad Jim, 1994. (scan)

- ^ a b c d Morris, Chris (22 June 1996). "R.L. Burnside Brews Blues on Matador". Billboard. pp. 10, 95. ISSN 0006-2510.

- ^ a b Ratliff, Ben (1997-03-15). "Delta Blues, Including Long Jokes And Lust". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2015-06-12.

- ^ "Critics' Poll – Chris Morris". Billboard. 28 December 1996. ISSN 0006-2510.

- ^ Cited in Dan DeLuca (1996-12-08). "This Is A Blues Band Of Another Color Purist? Not The Jon Spencer Blues Explosion. Spencer Calls Its Music "white Suburban Punk."". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Archived from the original on May 28, 2015. Retrieved 2015-05-03.

- ^ "Mr Wizard". Discogs.com. 1997.

- ^ OCLC 36765619

- ^ Matt Kelemen (1999-01-06). "Turning the tables on Burnside's deep blues". Orlando Weekly. Retrieved 2015-07-04.

- ^ a b Lou Friedman (Fall 1999). "Mississippi Remix, or how 73-year old R.L. Burnside found the hip-hop audience". Blues Access (39). Retrieved 2015-06-16.

- ^ "Burnside To Open For Beasties". MTV News. August 10, 1998. Archived from the original on June 24, 2015. Retrieved June 17, 2015.

- ^ "Slacking at the SXSW Film Festival". Indiewire. March 26, 1999. Retrieved 2016-03-10.

- ^ "[1999 Films at SXSW]" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-11. Retrieved 2016-03-10.

- ^ Steve Walker (August 23, 2001). "Bite Me". The Pitch. Retrieved 2016-03-10.

- ^ a b Lou Friedman (September 14, 2005). "Well Well Well...: R.L. Burnside 1926–2005". PopMatters. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- ^ "R.L. Burnside Scheduled For Heart Surgery". MTV News. August 30, 1999. Archived from the original on June 29, 2015. Retrieved June 17, 2015.

- ^ "R.L.Burnside recovering following heart surgery". CMJ New Music Report. October 4, 1999. p. 8. ISSN 0890-0795.

- ^ Marian Montgomery (2000-12-20). "R.L. Burnside Not Ready for Heaven Yet". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 2015-06-26.

- ^ Steve Newton (January 18, 2001). ""It's rough all over the world," says R.L. Burnside, "even down in Mississippi some." [reprint title]". The Georgia Straight. Retrieved 2015-11-10.

- ^ "Wish I Was In Heaven Sitting Down". Discogs.com. 24 October 2000. Retrieved 2015-11-10.

- ^ "A Bothered Mind, FP1013-2". Discogs.com. 2004.

- ^ Wish I Was in Heaven Sitting Down, review by Alex Henderson, allmusic

- ^ A Bothered Mind, review by Steve Leggett, allmusic

- ^ Andy Gill (2004-10-08). "Album: RL Burnside, A Bothered Mind, FAT POSSUM". The Independent. Archived from the original on February 19, 2014. Retrieved 2014-01-22.

- ^ a b "R.L. Burnside – Chart history". Billboard.com. Retrieved May 11, 2015.

- ^ Roni Sarig (2007). Third Coast: Outkast, Timbaland, and How Hip-Hop Became a Southern Thing. Da Capo Press. p. 221.

- ^ Morrison, Nick (January 12, 2011). "Dragging The Blues Into The 21st Century". A Blog Supreme / NPR. Retrieved 2015-10-29.

- ^ Steve Knopper (2004-11-21). "nublues". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 2015-11-04.

- ^ Sisario, Ben (2005-09-02). "R. L. Burnside, 78, Master of Raw Mississippi Blues, Dies". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2015-06-16.

- ^ "Music from TV Commercials – Spring 2002". Retrieved June 17, 2015.

- ^ "The complete list of nominees". Los Angeles Times. 2003-01-08. ISSN 0458-3035. Archived from the original on November 5, 2012. Retrieved 2015-06-21.

- ^ Eric Schumacher-Rasmussen (1998-06-09). "Fat Possum Raises Hackles With Off-Beat Blues". MTV News. Archived from the original on March 4, 2015. Retrieved 2015-07-16.

- ^ Jason Rewald (2009-06-18). "Hill Country Revue and Blues Evolution". TheDeltaBlues. Archived from the original on May 18, 2015. Retrieved April 23, 2015.

- ^ a b "Obituaries, R.L. Burnside". The South Reporter. September 15, 2005. Archived from the original on 2014-04-16.

- ^ "Obituaries". The South Reporter.

- ^ "Obituaries October 8, 2010". djournal, Northeast Mississippi daily journal.

- ^ "Memphis-area obituaries: December 9, 2010". The Commercial Appeal, Memphis.

- ^ Lisle, Andria (2004-06-12). "Local Beat: If the Juke Joint's a-Rockin'". Memphis Flyer. No Wayback or archive.today return for this URL. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-06-06.

- ^ Skelly, Richard. "Duwayne Burnside". Allmusic.

- ^ "Burnside Blues Cafe, Waterford MS | The Frontline". Thefrontlinemusic.wordpress.com. 2011-05-22. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- ^ "Alice Mae's Cafe | The Frontline". Thefrontlinemusic.com. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- ^ "Kent Burnside & The Flood Brothers". Play.google.com. Retrieved 2017-05-02.

- ^ "2000 - 21st W.C. Handy Blues Awards". PastBlues.

- ^ "2002 - 23rd W.C. Handy Blues Awards". PastBlues.

- ^ "Buddy Guy Wins Three W.C. Handy Honors". Billboard. May 24, 2002. Retrieved May 11, 2015.

- ^ "2003 - 24th W.C. Handy Blues Awards". PastBlues.

- ^ "[Blues music awards, all years]". PastBlues.

- ^ "The Blues Foundation Announces 2014 Blues Hall of Fame Inductees". American Blues Scene Magazine. February 12, 2014. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- ^ Fusilli, Jim (2015-10-06). "'St Germain' Review: Bamako by Way of Paris". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 2015-11-09.

- ^ Lou Erlanger. Liner notes to Acoustic Stories (1989/1997)

- ^ David Evans (2003). "Fife and drum Band". In John Shepherd; David Horn; Dave Laing; Paul Oliver; Peter Wicke (eds.). Continuum Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World, Volume 2: Performance and Production. Continuum Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World: Part 1, Performance and Production. A&C Black. pp. 27–28. ISBN 978-1-84714-472-0.

- ^ Ross Haenfler (8 October 2013). "Who are the "authentic" participants and who are the "poseurs"?". Subcultures: The Basics. Routledge. pp. 89–90. ISBN 978-1-134-54763-0.

- ^ E.g. on Well, Well, Well (2001) and Burnside on Burnside (2001)

External links

[edit]- 1926 births

- 2005 deaths

- 20th-century African-American male singers

- 20th-century American male singers

- 20th-century American singers

- American blues guitarists

- American male guitarists

- American blues singers

- Country blues musicians

- Juke Joint blues musicians

- Blues musicians from Mississippi

- Fat Possum Records artists

- People from Lafayette County, Mississippi

- People from Holly Springs, Mississippi

- 20th-century American guitarists

- Guitarists from Mississippi

- People from Byhalia, Mississippi

- African-American guitarists