Quinto (drum)

Oak Gon Bop quinto drum, c. 1976 | |

| Percussion instrument | |

|---|---|

| Classification | Membranophone |

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | 211.221.1 (Instruments in which the end without a membrane is open) |

| Developed | 19th century, Cuba |

| Related instruments | |

| congas: tres dos, tumba | |

| Musicians | |

| Chano Pozo, Mongo Santamaría, Candido Camero, Armando Peraza, Francisco Aguabella, Carlos "Patato" Valdés, Ray Barretto | |

The quinto (literally fifth in Spanish) is the smallest and highest pitched type of conga drum. It is used as the lead drum in Cuban rumba styles such as guaguancó, yambú, columbia and guarapachangueo, and it is also present in congas de comparsa. Quinto phrases are played in both triple-pulse (12/8, 6/8) and duple-pulse (4/4, 2/2) structures. In columbia, triple pulse is the primary structure and duple pulse is secondary. In yambú and guaguancó duple-pulse is primary and triple-pulse is secondary.[1]

Quinto performance in rumba

[edit]

The optimum expression of quinto phrasing is shaped by its interaction with the dance and the song, in other words, the complete social event, which is rumba.

Quinto interaction with the song

[edit]During the verses of the song the quinto is capable of sublime creativity, while musically subordinate to the lead vocalist. There are natural pauses in the cadence of the verses, typically one or two measures in length, where the quinto can play succinct phrases in the “holes” left by the singer. During the verses the quinto does not demonstrate technical virtuosity so much as taste and restraint.

Quinto interaction with the dance

[edit]Once the chorus (or montuno section) of the song begins, the phrases of the quinto interact with the dancers more than the lead singer. At this time, the phrases often accent cross-beats or offbeats. Many of the quinto phrases correspond directly to accompanying dance steps. The pattern of quinto strokes and the pattern of dance steps are at times identical, and at other times, imaginatively matched. The quinto player must be able to switch phrases immediately in response to the dancer’s ever-changing steps. The quinto vocabulary is used to accompany, inspire and in some ways, compete with the dancers' spontaneous choreography. Yvonne Daniel states: "The columbia dancer kinesthetically relates to the drums, especially the quinto . . . and tries to initiate rhythms or answer the riffs as if he were dancing with the drum as a partner."[2]

Individuality and creativity

[edit]Each quintero ('quinto player') interprets the requisite phrases in their own way. Quintero Armando Peraza (b. 1924) states: "Although there is a structure of rhythm in columbia, yambú, or guaguancó, the good rumbero will always follow the dancer’s steps and at the same time express his own individuality. Same thing with the dancer, who will have the ‘rules’ of that particular rumba to follow but will put his own particular stamp on each performance. Creativity and individuality has always been and still is the name of the game."[3]

With an emphasis on competition and individual creativity, the rhythmic vocabulary of quinto has evolved into a rich and pliable art form. The rhythmic phrasing heard in solos by percussion and other instruments in Cuban popular music, salsa, and Latin jazz, are often based on the quinto vocabulary. Quinto phrasing is also used as a means of varying the ostinato conga drum part called tumbao (see songo music).[4]

Modes

[edit]The quinto plays within two main rhythmic modes, corresponding to the two main modes of rumba dancing.[5]

The lock

[edit]The quinto lock mode is primarily a dyadic melody of slap and open tones, separated by an octave.[citation needed] The lock melody while constantly varied, maintains a specific relationship to clave, and corresponds to the basic side-to side rumba dance steps. The attack points of the lock and the basic steps are contained within a single cycle of clave (the key pattern of rumba). Put another way, the lock spans four main beats, or a single measure, as is written for this article.

Descendant of the African lead drum

[edit]Rumba is an amalgamation of several African drumming traditions, transplanted to Cuba during the time of slavery. Guaguancó and yambú are descended from the Cuban-Congolese fertility dances makuta and yuka. Columbia has cultural and musical ties to the Abakuá, a secret society from the Cross River region of present day southern Nigeria and northern Cameroon. The rhythmic phrasing of the abakuá lead drum bonkó enchemiyá is similar, and in some instances, identical to the quinto.[6] The following abakuá bonkó phrase is also played by the quinto in rumba. Regular noteheads indicate open tones and the triangle notehead indicates a slap.

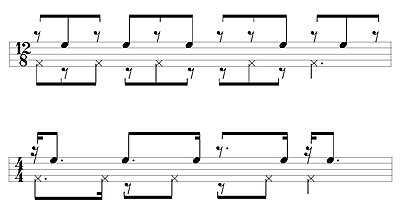

Displaced "clave"

[edit]The quinto plays in a contraclave ('counter-clave') fashion. In fact, the fundamental strokes of the quinto lock can be thought of as a displaced "clave."[7] The 12/8 version (Columbia) is a displaced triple-pulse “son clave” beginning on 1-and (the first offbeat). The 4/4 quinto lock (yambú and guaguancó) is a displaced “son clave,” beginning on 1-e (the first offbeat).

Alternating tone-slap melody

[edit]The attack-point pattern of the Matanzas-style lock is one clave in length, but its basic melodic structure is a two-clave phrase. The tone-slap melody usually reverses with every clave.[8] This style of quinto playing was made popular by the many recordings of Los Muñequitos de Matanzas (1956–present), the most famous rumba group from Matanzas. In the following example the melodic contour of the first measure (first clave cycle) of quinto is tone-slap-tone, while the contour of the second measure is the reverse: slap-tone-slap. The pattern is shown in both triple-pulse and duple-pulse structures.

Lock variations are created by doubling strokes (sounding the very next pulse), or eliminating strokes. Listen: Rumba quinto lock variations. The following example shows the sparsest form of the alternating lock melody. The first clave is tone-slap-tone, and the second clave is slap-tone-slap. The lock is usually constantly varied, but the example below is one of the few forms of the lock that is typically repeated.

Besides the typical rumba context, the lock is found in a form of Afro-Cuban sacred drumming called cajón pa’ los muertos. The quinto lock is the lead part when yambú is played in these ceremonies.[9]

Secondary resolution

[edit]The main emphasis of the lock is 1-e, the first offbeat in a measure of 4/4. Certain phrases resolving on 3-e are periodically used to interrupt the equilibrium of the lock mode. These can be thought of as secondary resolution phrases.[10] The following phrase concludes on 3-e.

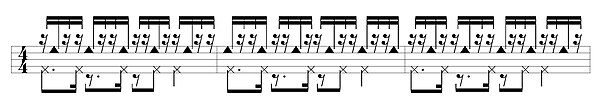

Havana born Mongo Santamaría (1917-2003) was a tremendous quintero, and at one time, the most famous conga drummer in the world. He was one of the first to record traditional rumba: Afro-Cuban Drums (1952), Changó (1954), Yambú (1958), Mongo (1959), and Bembé (1960). Santamaría's quinto phrasing was dynamic and creative; he had an unmistakable sound, that was uniquely his own. He did not analyze his personal style: “When I play I don’t know how I do it, or what I do ... I just play."[11] The following fourteen measure example is an excerpt from a quinto performance by Santamaría on his composition "Mi guaguancó" (1959).[12] The excerpt shows variations on two types of phrases: the lock (A) and the secondary resolution (B). Santamaría's repetition of what is ordinarily a secondary phrase (B), distinguishes this passage from the typical Matanzas-style approach. In measures 3, 4, 6, 7, and 13, 3-e is doubled, that is, the very next pulse (3-and) is also sounded.

The cross

[edit]4/4 cross-beat cycle

[edit]During the chorus section the quinto plays cross-beat phrases that contradict the meter by crossing the measure bar. In 4/4 cross-beats are generated by grouping the regular pulses (sixteenth-notes) in sets of three. In the following example every third pulse is sounded with a slap. The entire cross-beat cycle takes three claves (measures) to complete. The quinto is shown on the top line and clave is shown below. Like the lock, the cross begins on 1-e, the first offbeat.

Transitioning from the cross to the lock

[edit]The following nine-measure excerpt is from "La polémica" by Los Muñequitos de Matanzas (1988).[13] The structure of the passage consists of three sections of three measures each. The first two sections are complete cross-beat cycles (C). The last section combines a truncated cycle, a secondary resolution (B) and a measure of lock (A). The complete cross-beat cycles are abstracted by the combining of half-time cross-beats [pulses grouped in sets of six], regular cross-beats, and offbeats [grouped in threes]. The first cycle begins with half-time cross-beats and changes to regular cross-beats in measure three. The regular cross-beats continue into the second cycle but switch to an offbeat cross in measure six. Notice that the pattern of slaps in the offbeat phrase are the half-time cross-beats. The third cycle is truncated when the secondary resolution (B) is played in measure eight. In most cases the quinto pauses after sounding 3-e and 3-and, but the tones on beat 4, 4-e, and 4-a melodically connect measure eight with the lock phrase (A) in measure nine—Peñalosa.[14]

By alternating between the lock and the cross, the quinto creates larger rhythmic phrases that expand and contract over several clave cycles. The great Los Muñequintos quintero Jesús Alfonso (1949–2009) described this phenomenon as a man getting “drunk at a party, going outside for awhile, and then coming back inside."[15]

Quinto cross adopted to modern drum solos

[edit]The rhythmic vocabulary of quinto is the source of the most rhythmically dynamic phrases and passages heard in salsa and Latin jazz. Even with today’s flashy percussion solos, where snare rudiments and other highly developed techniques are used, analysis of the prevailing accents will reveal an underlying quinto structure, of which crossing is the most important.[citation needed]

Selected discography of quinto recordings

[edit]- Raíces africanas (AfroCuba de Matanzas) Shanachie CD 66009 (1996).

- Aniversario (Tata Güines) Egrem CD 0156 (1996).

- Guaguancó, v. 1 (Los Muñequitos [Grupo Guaguancó Matancero], Papin) Antilla CD 565 (1956, 1958).

- Guaguancó, v. 2 (Los Muñequitos [Grupo Guaguancó Matancero], Papin) Antilla CD 595 (1958).

- Rumba caliente (Los Muñequitos) Qbadisc CD 9005 (1977, 1988).

- Oye men listen... guaguancó (Los Papines) Bravo CD 105 [n.d.].

- Homenaje a mis colegas (Los Papines) Vitral CD 4105 (1989).

- Drums and Chants [Changó] (Mongo Santamaría) Vaya CD 56 (1954).

- Afro Roots [Yambú, Mongo] (Mongo Santamaría) Prestige CD 24018-2 (1958, 1959).

- Festival in Havana (Ignacio Piñeiro) Milestone CD 9337-2 (1955).

- Patato y Totico (Patato Valdés) Verve CD 5037 (1968).

- Guaguancó afro-cubano (Alberto Zayas) Panart 2055 (1955, 1956).

References

[edit]- ^ Peñalosa, David (2011: xxii) Rumba Quinto. Redway, CA: Bembe Books. ISBN 1-4537-1313-1

- ^ Danniel, Yvonne (1995: 69). Rumba: Dance and Social Change in Contemporary Cuba. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. ISBN 025320948X

- ^ Peñalosa (2011: 191) Peraza quoted by Peñalosa.

- ^ Santos, John (1985: 44) “Songo,” Modern Drummer Magazine, December.

- ^ Peñalosa (2011: xiv).

- ^ Peñalosa, David (2010: 186-191). The Clave Matrix; Afro-Cuban Rhythm: Its Principles and African Origins. Redway, CA: Bembe Inc. ISBN 1-886502-80-3

- ^ Peñalosa (2011: 1).

- ^ Spiro, Michael (2006: 34) The Conga Drummer’s Guidebook. Petaluma, CA: Sher Music Co.

- ^ Warden, Nolan (2006: 119). Cajón Los Muertos: Transculturation and Emergent Tradition in Afro-Cuban Ritual Drumming and Song. M.A. Thesis, Tufts University.

- ^ Peñalosa (2011: 41).

- ^ Gerard, Charley (2001: 29) Music from Cuba: Mongo Santamaría, Chocolate Armenteros, and Cuban Musicians in the United States. Santamaría quoted by Gerard. Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood Publishing Group.

- ^ "Mi guaguancó" (1:02), Mongo (Mongo Santamaría). Fantasy CD 8032 (1959).

- ^ "La polémica" (1:57), Rumba Caliente (Los Muñequitos de Matanzas) Qubadisc CD 9005 (1977, 1988).

- ^ Peñalosa (2011: 86).

- ^ Peñalosa (2011: 86). Alfonso quoted by Peñalosa.

External links

[edit]- "Yambú" by Conjunto Clave y Guaguancó, featuring Víctor Quesada "Tatín" on quinto. YouTube. The rumba dancer steps in tandem to quinto cross-beats at 3:09.