Annals of Quedlinburg

The first written instance of the name of Lithuania is in the Annals of Quedlinburg (1009) | |

| Original title | Annales Quedlinburgenses |

|---|---|

| Language | Latin |

| Subject | History |

The Annals of Quedlinburg (Latin: Annales Quedlinburgenses; German: Quedlinburger Annalen) were written between 1008 and 1030 in the convent of Quedlinburg Abbey. In recent years a consensus has emerged that it is likely that the annalist was a woman.[1] The annals are mostly dedicated to the history of the Holy Roman Empire; they also contain the first written mention of the name of Lithuania ("Litua"), in a description of an event dated to March 1009. The original document has disappeared, surviving only as a 16th-century copy held in Dresden,[2] but its contents endure as a scholarly resource.

Background

[edit]

The city of Quedlinburg, Germany, was first mentioned in writing in a document dated to 922. Saint Mathilda founded Quedlinburg Abbey, a religious community for women, there in 936, leading it until her death in 966. The abbey became a premier educational institution for the female nobles of the Duchy and Electorate of Saxony, and maintained its mission for nearly 900 years.[3][4] The city served as an imperial palatinate of the German emperors from the House of Liudolfings, where Henry the Fowler, the founder of that dynasty (House of Liudolfings), was buried.[5] Quedlinburg was situated not far from Magdeburg, the Royal Assembly of the empire, and its annalists could therefore rely on genuine information from the royal house and obtain eyewitness accounts.[5] The city lost some stature under the rule of Henry II, who broke with the tradition of celebrating Easter there; the Annals portray him unfavorably, and demonstrate the extent to which a royal monastery was entitled to criticize its monarch.[6]

Annals

[edit]The Annals open with a chronicle of world history from the time of Adam to the Third Council of Constantinople in 680-681, based on chronicles by Jerome, Isidore, and Bede.[3] The narrative is largely borrowed from multiple older sources until the year 1002, although original reports from as early as 852 are present. Beginning in 993, the narrative begins including events which represent the annalist's own eyewitness testimony concerning events at and around Quedlinburg.[3] The amount of detail increases significantly from 1008 onwards, leading some analysts to conclude that 1008 was the actual date that the Annals were first compiled, although Robert Holzman argues for a start date of 1000.[7] It has been suggested that the annalist temporarily abandoned the project between 1016 and 1021.[3] The exact reasons for this suspension of the work are unknown. Work on the project continued between 1021 and 1030, when its authors were able to report a military victory against Mieszko II Lambert, King of Poland.

The primary task of the annalists was to record the heritage of the Ottonian dynasty and of Quedlinburg itself. The Annals incorporate the stories of a number of historic and legendary figures such as Attila the Hun, King Dietrich of the Goths, and others.[3] The historian Felice Lifshitz has suggested that the amount of saga material integrated into its narrative is without parallel.[3]

The Annals of Quedlinburg became an important research source; during the 12th century they were used by at least five contemporary historians. Felice Lifshitz asserts that the Annals of Quedlinburg played a key role in shaping the ways in which influential Germans of the 19th and 20th centuries saw their medieval past.[3] They continue to be analyzed in other contexts: by scholars of Beowulf discussing its use of the term Hugones to mean Franks, by climatologists, and in a book discussing fear of the millennium.[7][8][9]

Mention of Lithuania

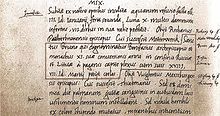

[edit]The first written occurrence of Lithuania's name has been traced to the Quedlinburg Annals in the descriotion of year 1009.[10][11] The passage reads:

Sanctus Bruno qui cognominatur Bonifacius archepiscopus et monachus XI. suæ conuersionis anno in confinio Rusciæ et Lituæ a paganis capite plexus cum suis XVIII, VII. Id. Martij petijt coelos.[12]

In English:

Saint Bruno, also called Boniface, archbishop and monk, in the eleventh year of his convertion, on border of Ruthenia and Lithuania was killed by the pagans together with 18 of his people on March 9th, and went to heaven.[13]

Regarding the translation of "VII. Id. Martij": in the Roman calendar dates were counted backward from three specific points in the lunar month. In this particular case, "VII. Id. Martij" literally means 7th of the Ides of March", i.e., around 15-7 = 8th or 9th of March.[14]

From other sources that describe Bruno of Querfurt, it is clear that this missionary attempted to Christianize the pagan king Netimer and his subjects.[15] However, Netimer's brother, refusing to accept Christianity, killed Bruno and his followers. The historian Alfredas Bumblauskas has suggested that the story records the first baptismal attempt in the history of Lithuania.[15]

Editions and translations

[edit]- Latin edition (including the Annals of Hildesheim and Weissemburg): MGH SS 3, pp. 18f.

- Giese, Martina, ed. (2004). Die Annales Quedlinburgenses (in Latin). Hannover: Hahnsche Buchhandlung. ISBN 3-7752-5472-2 («Monumenta Germaniae Historica. Scriptores rerum Germanicarum in usum scholarum separatim editi», 72).

- The Annals of the Holy Roman Empire. The Annals of Quedlinburg. Translated and annotated by Grzegorz Kazimierz Walkowski (Walkowski, Bydgoszcz, 2014) ISBN 978-83-930932-6-7

References

[edit]- ^ Thietmar of Merseburg; David Warner (2001). Ottonian Germany:The Chronicon of Thietmar of Merseburg. Manchester: Manchester Univ. Press. p. 43. ISBN 0-7190-4926-1.

- ^ "TO MARK THE MILLENNIUM OF LITHUANIA". Directorate for the Commemoration of the Millennium of Lithuania under the Auspices of the Office of the President of the Republic of Lithuania. Archived from the original on 3 October 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-02.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lifshitz, Felice (January 13, 2006). "Review to: Giese, ed., Annales Quedlinburgenses". The Medieval Review. Indiana University.

- ^ "Quedlinburg UNESCO World Heritage". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 2008-06-16. Retrieved 2008-09-02.

- ^ a b Alfredas Bumblauskas. Senosios Lietuvos istorija 1009-1795. 2005, p. 16 ISBN 9986-830-89-3

- ^ Reuter, Timothy; Rosamond McKitterick; David Abulafia (1999). The New Cambridge Medieval History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-36447-8.

- ^ a b Chase, Colin (1997). The Dating of Beowulf. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-7879-7.

- ^ Stothers, Richard B. (August 1998). "Far Reach of the Tenth Century Eldgjá Eruption, Iceland" (PDF). Climatic Change. 39 (4): 715–726. doi:10.1023/A:1005323724072. S2CID 127398721. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-10-21. Retrieved 2008-09-02.

- ^ Brody, Howard S. (2003). The Apocalyptic Year 1000: Religious Expectation and Social Change, 950–1050. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-511191-0.

- ^ Baranauskas, Tomas (Fall 2009). "On the Origin of the Name of Lithuania". Lituanus. 55 (3). ISSN 0024-5089. Archived from the original on 2021-07-09. Retrieved 2015-10-24.

- ^ Richard C. Frucht. Eastern Europe. 2004. p. 169 ISBN 1-57607-800-0

- ^ Albinus, Petrus Fabricius, Georg. Chronicon Quedlenburgense ab initio mundi per aetates. Retrieved on 2013-09-05

- ^ For Lithuania, a Millenium, Knight, vol. 31, no. 3, 2009

- ^ The Ides of March. Julius Caesar's Fateful Day

- ^ a b Alfredas Bumblauskas. Lietuvos tūkstantmetis – Millennium Lithuaniae Archived 2021-07-07 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 2009-09-01