Prospero Alpini

Prospero Alpini | |

|---|---|

Prospero Alpini (1553–1617) | |

| Born | 23 November 1553 |

| Died | 6 February 1617 (aged 63) |

| Nationality | Venetian |

| Alma mater | Padua University |

| Known for | Study of date palms |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Botany, Medicine |

| Institutions | Venice, Genoa, Padua |

| Author abbrev. (botany) | Alpino |

Prospero Alpini (also known as Prosper Alpinus, Prospero Alpinio and Latinized as Prosperus Alpinus) (23 November 1553 – 6 February 1617)[1] was a Venetian physician and botanist. He travelled around Egypt and served as the fourth prefect in charge of the botanical garden of Padua. He wrote several botanical treatises which covered exotic plants of economic and medicinal value. His description of coffee and banana plants are considered the oldest in European literature. The ginger-family genus Alpinia was named in his honour by Carolus Linnaeus.

Biography

[edit]

Born at Marostica, a town near Vicenza, the son of Francesco, a physician, Alpini served in his youth for a time in the Milanese army, but in 1574 he went to study medicine at Padua. After taking his doctor's degree in 1578, he settled as a physician in Campo San Pietro, a small town in the Paduan territory. But his tastes were botanical and influenced by Melchiorre Guilandino, and to extend his knowledge of exotic plants he travelled to Egypt in 1580 as physician to Giorgio Emo, the Venetian consul in Cairo.[2] The position was obtained with help from Antonio Morosini. From 1587 to 1590 he worked in Venice, Bassano and then at Genoa as physician to Giovanni Andrea Doria.[3]

In Egypt he spent three years, and from a practice in the management of datepalms, which he observed in that country, he learned of sexual difference in plants, which was later to become important in the foundation of the Linnaean taxonomy system. He says that "the female date-trees or palms do not bear fruit unless the branches of the male and female plants are mixed together; or, as is generally done, unless the dust found in the male sheath or male flowers is sprinkled over the female flowers".[1]

On his return, he resided for some time at Genoa as physician to Andrea Doria, and in 1593 he was appointed professor of botany at Padua. In 1603, following the death of Giacomo Antonio Cortuso (1513-1603), he was appointed prefect for the botanical garden at Padua. His knowledge of medicinal plants made him a much sought after physician consulted by others such as Fabrici of Acquapendente and Alessandro Massaria. Towards the end of his life he suffered from arthritis, skin inflammation and receptive aphasia. He died on 6 February 1617 and is buried in the Basilica of Saint Antonio. He was succeeded in the botanical chair by his son Alpino Alpini (died 1637).[1][4]

Books

[edit]

Alpini's best-known botanical work is De Plantis Aegypti liber (Venice, 1592).[1] This work introduced a number of plant species previously unknown to European botanists including[5] Abrus, Abelmoschus, Lablab, and Melochia, each of which are native to tropical areas and were cultivated with artificial irrigation in Egypt at the time. Other species included Sesban Sesbania sesban and the baobab tree (which he spelled bahobab). Early adopters of Alpini's new botanical names included the botanists Carolus Clusius (died 1609), Johann Bauhin (died 1613), Caspar Bauhin (died 1624) and Johann Veslingius (visited Egypt in the 1620s; died 1649).[6]

Prospero Alpini's De Plantis Exoticis was published in 1629 after his death. It has an expansion of the material in De Plantis Aegypti plus some other material. His De Plantis Aegypti liber is said to contain the first account of the coffee plant published in Europe although the German traveller Leonhard Rauwolf tasted coffee at Aleppo in 1573 and described its effects in 1582.[7][8] His book De balsamo dialogus (1581, 1592) was among the first books to specialize on a single group of plants. He wrote on the prognosis of diseases in his De praesagienda vita et morti aegrotanti (1601) which led Kurt Sprengel to consider him as a modern father of diagnostic science.[9] Another work that took nearly a decade was the De medicina methodica libri tredecim (1611) which sought a revival of the Methodic school of medicine.[10] His works De plantis exoticis and the Rerum Aegyptiarum libri IV were published posthumously.

The genus Alpinia, belonging to the order Zingiberaceae (ginger family), was named after him by Linnaeus.[1]

Works

[edit]- De balsamo dialogus, 1581, 1592.

- De medicina Aegyptiorum, 1591.

- De plantis Aegypti, Venice, 1592.

- De praesagienda vita et morte aegrotantium, 1601.

- De medicina methodica, 1611.

- De Plantis Exoticis, 1629.

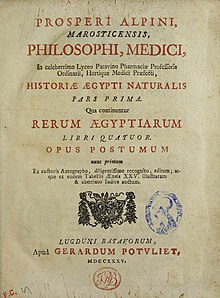

- Rerum Aegyptiarum libri IV, 1735.

- "Historia Aegypti naturalis" (in Latin). Leiden. Gerrit Potvliet. 1735.

- "Historia Aegypti naturalis" (in Latin). Leiden. Gerrit Potvliet. 1735.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Alpini, Prospero". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 737.

- ^ Zago, Roberto. "EMO, Giorgio". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani. Treccani. Retrieved 7 November 2024.

- ^ De Santo, Natale G.; Aliotta, Gianni; Bisaccia, Carmela; Di Iorio, Biagio; Cirillo, Massimo; Ricciardi, Biagio; Savica, Vincenzo; Ongaro, Giuseppe (2013). "De Medicina Aegyptiorum by Prospero Alpini (Venice, Franciscus de Franciscis, 1591)" (PDF). Journal of Nephrology. 26 (Suppl. 22): 117–123. doi:10.5301/jn.5000354 (inactive 1 November 2024). PMID 24375355.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ Stannard, Jerry (1970). "Alpini, Prospero". Dictionary of Scientific Biography. Vol. 1. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 124–125. ISBN 978-0-684-10114-9.

- ^ Etymologisches Wörterbuch der botanischen Pflanzennamen, by Helmut Genaust, year 1996. See under each species name; book is alphabetically organized.

- ^ E.g. Carolus Clusius year 1601 (in Latin), Prospero Alpini and Johann Veslingius year 1640 (in Latin), John Ray year 1686 quoting the Bauhin brothers (in Latin).

- ^ Rauwolf, L. (1582). Aigentliche Beschreibung der Raib inn die Morgenlaender, so er vor diser Zeit gegen Auffgang in die Morgenlaender. Fuernemlich Syriam, Arabiam, Mesopotamiam, Asyriam, Armeniam, nicht ohne geringe Muehe und grosse gefahr selbs volbracht. Laugingen.

- ^ Friis, I. (2015). "Coffee and qat on the Royal Danish expedition to Arabia – botanical, ethnobotanical and commercial observations made in Yemen 1762–1763". Archives of Natural History. 42 (1): 101–112. doi:10.3366/anh.2015.0283.

- ^ Adams, W.H. Davenport (1887). The Healing Art. Volume I. (2 ed.). London: Ward and Downey. p. 107.

- ^ de Santo, Natale Gaspare; Bisaccia, Carmela; Ricciardi, Biagio; Anastasio, Pietro; Aliotta, Giovanni; Ongaro, Giuseppe (2016). "Disease of the kidney and of the urinary tract in De Medicina Methodica (Padua, 1611) of Prospero Alpini (1563-1616)" (PDF). Giornale Italiano di Nefrologia. 33: 1–66.

- ^ International Plant Names Index. Alpino.

External links

[edit]- Prosperi Alpini De Balsamo dialogus . Franciscus de Franciscis, Venitiis 1591 Digital edition by the University and State Library Düsseldorf

- Prosperi Alpini De medicina Aegyptiorum : libri quatuor; in quibus Multa cum de vario mittendi Sanguinis Usu per Venas, Arterias, Cucurbitulas, ac Scarificationes nostris inusitatas, deq[ue] Inustionibus, & alijs chyrurgicis Operationibus, tum de quamplurimis Medicamentis apud Aegyptios frequentioribus, elucescunt . Franciscus de Franciscis, Venetiis 1591 Digital edition by the University and State Library Düsseldorf

- Prosperi Alpini De Plantis Aegypti liber : in quo non pauci, qui circa Herbarum Materiam irrepserunt, Errores, deprehenduntur, quorum Causa hactenus multa Medicamenta ad Usum Medicinae admodum expetenda, plerisque Medicorum, non sine Artis Iactura, oculta, atque obsoleta iacuerunt. Franciscus de Franciscis, Venitiis 1592 Digital edition by the University and State Library Düsseldorf

- De Plantis Exoticis, by Prosperi Alpini, year 1629, in Latin.

- De Plantis Aegypti liber, by Prosperi Alpini with comments by Johann Vesling, published year 1640, in Latin.

- Online Galleries, History of Science Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries High resolution images of works by and/or portraits of Prospero Alpini in .jpg and .tiff format. Includes some pages from the 1592 edition of De Plantis Aegypti liber.

- De praesagienda vita et morte aegrotantium libri septem (1754)

- De Plantis Aegypti, by Prosperi Alpini, Latin transcription and English translation with notes on the grammar and the orthography of the text, by Ian L. Plamondon, published 2016. Barrett, The Honors College Thesis/Creative Project Collection, Arizona State University.