Earl of Chester

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2022) |

| Earldom of Chester subsidiary of Principality of Wales since 1343 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Creation date | 1067 (first creation) 1071 (second creation) 1254 (third creation) 1264 (fourth creation) 1301 (fifth creation) 1312 (sixth creation) see Prince of Wales for further creations |

| Created by | William the Conqueror (first creation) William the Conqueror (second creation) Henry III (third creation) Henry III (fourth creation) Edward I (fifth creation) Edward II (sixth creation) |

| Peerage | Peerage of the United Kingdom |

| First holder | Gerbod the Fleming, 1st Earl of Chester |

| Present holder | William, Prince of Wales[1] |

| Heir apparent | Non-Hereditary |

| Extinction date | 1070 (first creation) 1237 (second creation) 1272 (third creation) 1265 (fourth creation) 1307 (fifth creation) 1327 (sixth creation) |

| Former seat(s) | Chester Castle |

| Motto | Ich dien (I serve) |

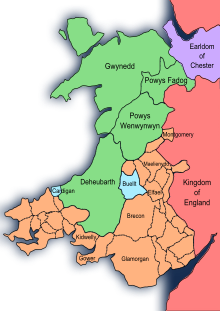

The Earldom of Chester (Welsh: Iarllaeth Caer) was one of the most powerful earldoms in medieval England, extending principally over the counties of Cheshire and Flintshire. Since 1301 the title has generally been granted to heirs apparent to the English throne, and after 1707 the British throne. From the late 14th century, it has been given only in conjunction with that of Prince of Wales.

Honour of Chester and County Palatinate

[edit]The County of Cheshire was held by the powerful Earls (or "Counts" from the Norman-French) of Chester from the late eleventh century, and they held land all over England, comprising "the honour of Chester". By the late twelfth century (if not earlier) the earls had established a position of power as quasi-princely rulers of Cheshire that led to the later establishment of the County Palatine of Chester and Flint. Such was their power that Magna Carta set down by King John did not apply to Cheshire and the sixth earl was compelled to issue his own version.[3]

County palatine

[edit]

The earldom passed to the Crown by escheat in 1237 on the death of John the Scot, Earl of Huntingdon, seventh and last of the Earls. William III de Forz, 4th Earl of Albemarle, claimed the earldom as husband of Christina, the senior co-heir, but the king persuaded them to quitclaim their rights in 1241 in exchange for modest lands elsewhere. The other co-heiresses did likewise.[5] It was annexed to the Crown in 1246. King Henry III then passed the Lordship of Chester, but not the title of Earl, to his son, the Lord Edward, in 1254; as King Edward I, this son in turn conferred the title and lands of the Earldom on his son, Edward, the first English Prince of Wales. By that time, the Earldom of Chester consisted of two counties: Cheshire and Flintshire.

The establishment of royal control of the Earldom of Chester made possible King Edward I's conquest of north Wales, and Chester played a vital part as a supply base during the Welsh Wars (1275–84), so the separate organisation of a county palatine was preserved. This continued until the time of King Henry VIII. Since 1301, the Earldom of Chester has always been conferred on the Princes of Wales.

Briefly promoted to a principality in 1398 by King Richard II, who titled himself "Prince of Chester",[6] it was reduced to an earldom again in 1399 by King Henry IV. Whereas the Sovereign's eldest son is automatically Duke of Cornwall, he must be made or created Earl of Chester as well as Prince of Wales.

The independent palatinate jurisdiction of Chester survived until the time of King Henry VIII (1536), when the earldom was brought more directly under the control of the Crown. The palatinate courts of Great Sessions and Exchequer survived until the reforms of 1830.

The importance of the County Palatinate of Chester is shown by the survival of Chester Herald in the College of Arms for some six hundred years. The office has anciently been nominally under the jurisdiction of Norroy King of Arms.

Revenues

[edit]In the year 1377, the revenues of the Earldom were recorded as follows:[7]

County of Chester

[edit]- Fee-Farm of city of Chester – £22 2 4 1/2,

- Escheated lands of said city – £0 7 0,

- Rents of the Manor of Dracklow and Rudeheath – £26 2 6,

- Farm of Medywick – £21 6 0,

- Profits of Mara and Modren – £34 0 9,

- Profits of Shotwick Manor and Park – £23 19 0,

- Mills upon River Dee – £11 0 0,

- Annual profits of Fordham Manor – £48 0 0,

- Profits of Macklefield Hundred – £6 1 8,

- Farm of Macklefield Borough – £16 1 3,

- Profits of the forest of Macklefield £85 12 11 3/4,

- Profits of escheater of Chester – £24 19 0,

- Profits of the sheriff of said county – £43 12 3,

- Profits of the Chamberlain of county – £55 14 0.

County of Flint

[edit]- Yearly value of Ellow – £20 8 0,

- Farm of the town of Flint – £33 19 4,

- Farm of Cayrouse – £7 2 4,

- Castle of Ruthlam – £5 12 10,

- Rents and profits of Mosten – £7 0 0,

- Rents and profits of Colshil – £54 16 0,

- Rents of Ruthlam town – £44 17 6,

- Lands of Englefield (yearly) – £23 10 0,

- Profits of Vayvol – £5 9 0,

- Profits of the office of escheator – £6 11 9,

- Mines of Cole and Wood within Manor of Mosten – £0 10 0,

- Office of the sheriff in rents and casualties – £120 0 0,

- Mines and profits of the Fairs of Northope – £3 9 2,

- Casualties was lastly – £37 0 8.

Total income was £418 1 2 3/4 from Cheshire and £181 6 0 from Flintshire.

List of the Earls of Chester

[edit]First Creation (1067–1070)

[edit]Second Creation (1071)

[edit]- 1071–1101 Hugh d'Avranches, 1st Earl of Chester (died 1101)[8][9]

- 1101–1120 Richard d'Avranches, 2nd Earl of Chester (1094–1120)

- 1120–1129 Ranulf le Meschin, 3rd Earl of Chester (died c. 1129)

- 1129–1153 Ranulf de Gernon, 4th Earl of Chester (died c. 1153)

- 1153–1181 Hugh de Kevelioc, 5th Earl of Chester (1147–1181)

- 1181–1232 Ranulf de Blondeville, 6th Earl of Chester (c. 1172–1232)

- 1232–1232 Matilda of Chester, Countess of Chester suo jure (1171–1233) (Inherited Oct 1232 inter vivos gift to son Nov 1232)

- 1232–1237 John of Scotland, 7th Earl of Chester (c. 1207–1237)

(dates above are approximate)

Third Creation (1254)

[edit]- Edward, Lord of Chester, but without the title of earl (1239–1307) (became King Edward I in 1272)

Fourth Creation (1264)

[edit]- Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester, 1st Earl of Chester (1208–1265) (forfeit 1265)

(There is no evidence that Alphonso, elder son of Edward I, was created earl of Chester, although he was styled as such)

Fifth Creation (1301)

[edit]- Edward of Caernarvon, Earl of Chester (1284–1327) (became King Edward II in 1307)

Sixth Creation (1312)

[edit]- Edward Plantagenet, Earl of Chester (1312–1377) (became King Edward III in 1327)

Thereafter, the Earldom of Chester was created in conjunction with the Principality of Wales. See Prince of Wales for further earls of Chester.

Other associations

[edit]- Earl of Chester was one of the GWR 3031 Class locomotives that were built for and ran on the Great Western Railway between 1891 and 1915.

Family tree

[edit]| Family tree of the Princes of Wales, Dukes of Cornwall, Dukes of Rothesay, Earls of Carrick and Earls of Chester | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

[edit]- History of Cheshire

- Constable of Chester

- Countess of Chester, a subsidiary title of the Princess of Wales

References

[edit]- ^ "Crown Office". The London Gazette. 24 February 2023. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ Tomlinson, H Ellis (1956). The Heraldry of Cheshire. Manchester: Manchester University Press. p. 159.

- ^ Lush, Jane (15 January 2015). "Cheshire's Own Magna Carta". Tarvin Online. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

- ^ Wrexham County Borough Council: The Princes and the Marcher Lords

- ^ "Forz , William de, count of Aumale (b. before 1216, d. 1260)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/29480. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ William Camden, Cheshire – Britannia : "Richard himself was styled Princeps Cestriæ, Prince of Chester. But this title was but of small duration: no longer, than till Henry the fourth repeal’d the Laws of the said Parliament; for then it became a County Palatine again, and retains that Prerogative to this day...".

- ^ Doddridge, John (1714). An historical account of the ancient and modern state of the principality of Wales, dutchy of Cornwall, and earldom of Chester. London, Printed for J. Roberts. pp. 132–136.

- ^ Cunliffe, Barry W. (2001). The Penguin atlas of British & Irish history. Penguin. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-14-100915-5. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- ^ The New Encyclopædia Britannica: Micropaedia. Encyclopædia Britannica. 1995. p. 180. ISBN 978-0-85229-605-9. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

Further reading

[edit]- Harris, BE (1979). "Administrative History". In Elrington, CR (ed.). The Victoria County History of Chester. Vol. II. University of London Institute of Historical Research. pp. 1–97.

- Earls of Chester

- Norman conquest of England

- Succession to the British crown

- Earldoms in the Peerage of England

- British and Irish peerages which merged in the Crown

- Noble titles created in 1070

- Noble titles created in 1071

- Noble titles created in 1121

- Noble titles created in 1232

- Noble titles created in 1254

- Noble titles created in 1264

- Noble titles created in 1301

- Noble titles created in 1333

- Noble titles created in 1376

- Noble titles created in 1399

- Noble titles created in 1454

- Noble titles created in 1471

- Noble titles created in 1483

- Noble titles created in 1489

- Noble titles created in 1504

- Noble titles created in 1610

- Noble titles created in 1616

- Noble titles created in 1714

- Noble titles created in 1729

- Noble titles created in 1751

- Noble titles created in 1762

- Noble titles created in 1841

- Noble titles created in 1901

- Noble titles created in 1910

- Noble titles created in 1958

- Charles III

- William, Prince of Wales